Moving from a Monologue to a Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL Millenniumpost.In

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL millenniumpost.in pages millenniumpost NO HALF TRUTHS th28 NEW DELHI & KOLKATA | MAY 2018 Contents “Dharma and Dhamma have come home to the sacred soil of 63 Simplifying Doing Trade this ancient land of faith, wisdom and enlightenment” Narendra Modi's Compelling Narrative 5 Honourable President Ram Nath Kovind gave this inaugural address at the International Conference on Delineating Development: 6 The Bengal Model State and Social Order in Dharma-Dhamma Traditions, on January 11, 2018, at Nalanda University, highlighting India’s historical commitment to ethical development, intellectual enrichment & self-reformation 8 Media: Varying Contours How Central Banks Fail am happy to be here for 10 the inauguration of the International Conference Unmistakable Areas of on State and Social Order 12 Hope & Despair in IDharma-Dhamma Traditions being organised by the Nalanda University in partnership with the Vietnam The Universal Religion Buddhist University, India Foundation, 14 of Swami Vivekananda and the Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. In particular, Ethical Healthcare: A I must welcome the international scholars and delegates, from 11 16 Collective Responsibility countries, who have arrived here for this conference. Idea of India I understand this is the fourth 17 International Dharma-Dhamma Conference but the first to be hosted An Indian Summer by Nalanda University and in the state 18 for Indian Art of Bihar. In a sense, the twin traditions of Dharma and Dhamma have come home. They have come home to the PMUY: Enlightening sacred soil of this ancient land of faith, 21 Rural Lives wisdom and enlightenment – this land of Lord Buddha. -

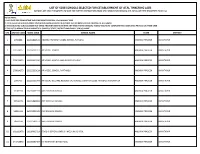

List of 6038 Schools Selected for Establishment of Atal Tinkering

LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. LAST DATE FOR COMPLETING THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS : 31st JANUARY 2020 2. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST OPEN A NEW BANK ACCOUNT IN A PUBLIC SECTOR BANK FOR THE PURPOSE OF ATL GRANT. 3. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST NOT SHARE THEIR INFORMATION WITH ANY THIRD PARTY/ VENDOR/ AGENT/ AND MUST COMPLETE THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS ON THEIR OWN. 4. THIS LIST IS ARRANGED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF STATE, DISTRICT AND FINALLY SCHOOL NAME. S.N. ATL UID CODE UDISE CODE SCHOOL NAME STATE DISTRICT 1 2760806 28222800515 ANDHRA PRADESH MODEL SCHOOL PUTLURU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 2 132314217 28224201013 AP MODEL SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 3 574614473 28223600320 AP MODEL SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 4 278814373 28223200124 AP MODEL SCHOOL RAPTHADU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 5 2995459 28222500704 AP SOCIAL WELFARE RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR GIRLS KURUGUNTA ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 6 13701194 28220601919 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 7 15712075 28221890982 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 8 56051196 28222301035 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 9 385c1160 28221591153 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 10 102112978 28220902023 GOOD SHEPHERD ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 11 243715046 28220590484 K C NARAYANA E M SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. -

Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

S T Q Contents SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Issue 17 March 1998 2 EDITORIAL Editor 3 Anjum Katyal ‘UNPEELING THE LAYERS WITHIN YOURSELF ’ Editorial Consultant Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry Samik Bandyopadhyay 22 Project Co-ordinator A GATKA WORKSHOP : A PARTICIPANT ’S REPORT Paramita Banerjee Ramanjit Kaur Design 32 Naveen Kishore THE MYTH BEYOND REALITY : THE THEATRE OF NEELAM MAN SINGH CHOWDHRY Smita Nirula 34 THE NAQQALS : A NOTE 36 ‘THE PERFORMING ARTIST BELONGED TO THE COMMUNITY RATHER THAN THE RELIGION ’ Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry on the Naqqals 45 ‘YOU HAVE TO CHANGE WITH THE CHANGING WORLD ’ The Naqqals of Punjab 58 REVIVING BHADRAK ’S MOGAL TAMSA Sachidananda and Sanatan Mohanty 63 AALKAAP : A POPULAR RURAL PERFORMANCE FORM Arup Biswas Acknowledgements We thank all contributors and interviewees for their photographs. 71 Where not otherwise credited, A DIALOGUE WITH ENGLAND photographs of Neelam Man Singh An interview with Jatinder Verma Chowdhry, The Company and the Naqqals are by Naveen Kishore. 81 THE CHALLENGE OF BINGLISH : ANALYSING Published by Naveen Kishore for MULTICULTURAL PRODUCTIONS The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Jatinder Verma 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 86 MEETING GHOSTS IN ORISSA DOWN GOAN ROADS Printed at Vinayaka Naik Laurens & Co 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Dear friend, Four years ago, we started a theatre journal. It was an experiment. Lots of questions. Would a journal in English work? Who would our readers be? What kind of material would they want?Was there enough interesting and diverse work being done in theatre to sustain a journal, to feed it on an ongoing basis with enough material? Who would write for the journal? How would we collect material that suited the indepth attention we wanted to give the subjects we covered? Alongside the questions were some convictions. -

Program and Abstracts

Indian Council for Cultural Relations. Consulate General of India in St.Petersburg Russian Academy of Sciences, St.Petersburg scientific center, United Council for Humanities and Social Sciences. Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) RAS. Institute of Oriental Manuscripts RAS. Oriental faculty, St.Petersburg State University. St.Petersburg Association for International cooperation GERASIM LEBEDEV (1749-1817) AND THE DAWN OF INDIAN NATIONAL RENAISSANCE Program and Abstracts Saint-Petersburg, October 25-27, 2018 Индийский совет по культурным связям. Генеральное консульство Индии в Санкт-Петербурге. Российская академия наук, Санкт-Петербургский научный центр, Объединенный научный совет по общественным и гуманитарным наукам. Музей антропологии и этнографии (Кунсткамера) РАН. Институт восточных рукописей РАН Восточный факультет СПбГУ. Санкт-Петербургская ассоциация международного сотрудничества ГЕРАСИМ ЛЕБЕДЕВ (1749-1817) И ЗАРЯ ИНДИЙСКОГО НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ВОЗРОЖДЕНИЯ Программа и тезисы Санкт-Петербург, 25-27 октября 2018 г. PROGRAM THURSDAY, OCTOBER 25 St.Peterburg Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences, University Embankment 5. 10:30 – 10.55 Participants Registration 11:00 Inaugural Addresses Consul General of India at St. Petersburg Mr. DEEPAK MIGLANI Member of the RAS, Chairman of the United Council for Humanities and Social Sciences NIKOLAI N. KAZANSKY Director of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Associate Member of the RAS ANDREI V. GOLOVNEV Director of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, Professor IRINA F. POPOVA Chairman of the Board, St. Petersburg Association for International Cooperation, MARGARITA F. MUDRAK Head of the Indian Philology Chair, Oriental Faculty, SPb State University, Associate Professor SVETLANA O. TSVETKOVA THURSDAY SESSION. Chaiperson: S.O. Tsvetkova 1. SUDIPTO CHATTERJEE (Kolkata). -

![T]Ntversity of Hyderabai) S.N.School Of' Arts and Communication](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7858/t-ntversity-of-hyderabai-s-n-school-of-arts-and-communication-147858.webp)

T]Ntversity of Hyderabai) S.N.School Of' Arts and Communication

I Code No: B-30 T]NTVERSITY OF HYDERABAI) S.N.SCHOOL OF' ARTS AND COMMUNICATION ENTRANCE EXAMINATION. F'EBRUARY _ 2013 M.P.A OHEATRE ARTS) Max. Marks:50 Hall TicketNo. Instructions: i) Write ]our .+- -*r-rz Hall Ticket Number in OMR Answer Sheet given to you. Also write the Hall Ticket Number in the space provided above. iD There is negative marking. Each wrong answer carries -0.33 mark. iii) Answers are to be marked on OMR answer sheet following the instructions provided there upon. iv) Hand over the OMR answer sheet at the end of the examination to the Invigilator. v) No additional sheets will be provided. Rough work can be done in the question paper itself / space provided at the end of the booklet. vi) The question paper.un t" taf<in Uy tfre canaiaates at the end of the examination. 1. The author of the play "Hayavadana" is A) K.Krisbnaiah B) Choramaswami C) Girish Karnad D) Bharatendu Harischandra 2. Guru Kelucharan Mahapathra is an exponent of the form A) Satriya B) Odissi C) Katthak D) Kuchipudi L B -eo 3. World Theatre day is celebrated on A) April26 B) January 31 C) August 15 D)March27 4. M.F.Hussain is a noted A) Painter B) Violinist C) Singer D) Architect 5. The director of play "Charan Das Chor" of Naya Theatre group is A) Vrjay Tendulkar B) Habib Tanvir C) Utpal Dutt D) B.V.Karanth 6. The Golkonda Fort is situated at A) Mumbai B) Hyderabad C) Bhuvaneswar D) Madhurai 7. Number of Vedas are A)2 B) 8 c)4 D) s 8. -

The Actresses of the Public Theatre in Calcutta in the 19Th & 20Th Century

Revista Digital do e-ISSN 1984-4301 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da PUCRS http://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/ojs/index.php/letronica/ Porto Alegre, v. 11, n. esp. (supl. 1), s113-s124, setembro 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1984-4301.2018.s.30663 Memory and the written testimony: the actresses of the public theatre in Calcutta in the 19th & 20th century Memória e testemunho escrito: as atrizes do teatro público em Calcutá nos séculos XIX e XX Sarvani Gooptu1 Netaji Institute for Asian Studies, NIAS, in Kolkata, India. 1 Professor in Asian Literary and Cultural Studies ABSTRACT: Modern theatrical performances in Bengali language in Calcutta, the capital of British colonial rule, thrived from the mid-nineteenth at the Netaji Institute for Asian Studies, NIAS, in Kolkata, India. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1564-1225 E-mail: [email protected] century though they did not include women performers till 1874. The story of the early actresses is difficult to trace due to a lack of evidence in primarycontemporary material sources. and the So scatteredthough a researcher references is to vaguely these legendary aware of their actresses significance in vernacular and contribution journals and to Indian memoirs, theatre, to recreate they have the remained stories of shadowy some of figures – nameless except for those few who have left a written testimony of their lives and activities. It is my intention through the study of this Keywords: Actresses; Bengali Theatre; Social pariahs; Performance and creative output; Memory and written testimony. these divas and draw a connection between testimony and lasting memory. -

Annual Report 1983-84

ANNUAL REPORT (1983-84) A NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL PLANNING AND ADMINISTRATION 17-B, SRI AUROBINDO MARG NEW DELHI APRIL 1985 ©NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL PLANNING AND ADM INISTRATION, 1985 Natif A t ' p U m i 4 17-B, ^ DOC, No I - ' Edited, Designed and Printed by Balakrishna Selvaraj, Publication Officer, National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration, 17-B, Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi-110016 printed at Allied Publishers Pvt. Ltd., A-104 Mayapuri, Phase 11, New Delhi 110064 CONTENTS Page Objectives Acknowledgements An Overview 1 - 19 PART I : TRAINING PROGRAMMES 20 - U\ PART II : RESEARCH AND STUDIES hi - 72 PART III : ADVISORY, CONSULTANCY AND SUPPORT SERVICES 73 - 87 PART IV : OTHER ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES 88 - 93 PART V : ACADEMIC UNITS 9^ - 102 PART VI : ACADEMIC INFRASTRUCTURE 103 - 112 PART VII : ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE 113 - 126 ANNEXURES I. Training Programmes 127 - 161 II. Research Studies 162 - 185 III. Academic Contribution of Faculty 186 - 207 IV. Visitors 208 - 209 APPENDICES I. List of Members of the Council of NIEPA 210 - 212 II. List of Members of the Executive 213 Committee of NIEPA III. List of Members of Finance Committee of NIEPA IIU IV. List of Members of the Programme Advisory 215 Committee of NIEPA V. List of Members of the Publication 216 Advisory Committee of NIEPA VI. List of Faculty and Research Staff of NIEPA 217 - 219 VII. Annual Accounts and Audit Report 220 - 258 THE AIMS AND OBJECTIVES OF THE INSTITUTE (a) To organise pre-service and in-service training, conferences, workshops, -

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

Lions Film Awards 01/01/1993 at Gd Birla Sabhagarh

1ST YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 01/01/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR TAPAS PAUL for RUPBAN BEST ACTRESS DEBASREE ROY for PREM BEST RISING ACTOR ABHISEKH CHATTERJEE for PURUSOTAM BEST RISING ACTRESS CHUMKI CHOUDHARY for ABHAGINI BEST FILM INDRAJIT BEST DIRECTOR BABLU SAMADDAR for ABHAGINI BEST UPCOMING DIRECTOR PRASENJIT for PURUSOTAM BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR MRINAL BANERJEE for CHETNA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER USHA UTHUP BEST PLAYBACK SINGER AMIT KUMAR BEST FILM NEWSPAPER CINE ADVANCE BEST P.R.O. NITA SARKAR for BAHADUR BEST PUBLICATION SUCHITRA FILM DIRECTORY SPECIAL AWARD FOR BEST FILM PREM TELEVISION BEST SERIAL NAGAR PARAY RUP NAGAR BEST DIRECTOR RAJA SEN for SUBARNALATA BEST ACTOR BHASKAR BANERJEE for STEPPING OUT BEST ACTRESS RUPA GANGULI for MUKTA BANDHA BEST NEWS READER RITA KAYRAL STAGE BEST ACTOR SOUMITRA CHATTERHEE for GHATAK BIDAI BEST ACTRESS APARNA SEN for BHALO KHARAB MAYE BEST DIRECTOR USHA GANGULI for COURT MARSHALL BEST DRAMA BECHARE JIJA JI BEST DANCER MAMATA SHANKER 2ND YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 24/12/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR CHIRANJEET for GHAR SANSAR BEST ACTRESS INDRANI HALDER for TAPASHYA BEST RISING ACTOR SANKAR CHAKRABORTY for ANUBHAV BEST RISING ACTRESS SOMA SREE for SONAM RAJA BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS RITUPARNA SENGUPTA for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST FILM AGANTUK OF SATYAJIT ROY BEST DIRECTOR PRABHAT ROY for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR BABUL BOSE for MON MANE NA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER INDRANI SEN for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER SAIKAT MITRA for MISTI MADHUR BEST CINEMA NEWSPAPER SCREEN BEST FILM CRITIC CHANDI MUKHERJEE for AAJKAAL BEST P.R.O. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

Music, Partition and Ghatak Priyanka Shah

Of roots and rootlessness: music, partition and Ghatak Priyanka Shah Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 120–136 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 120 Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 120–136 Of roots and rootlessness: music, partition and Ghatak Priyanka Shah Maulana Azad College, University of Calcutta, [email protected] At a time when the ‘commercial’ Bengali film directors were busy caricaturing the language and the mannerisms of the East-Bengal refugees, specifically in Calcutta, using them as nothing but mere butts of ridicule, Ritwik Ghatak’s films portrayed these ‘refugees’, who formed the lower middle class of the society, as essentially torn between a nostalgia for an utopian motherland and the traumatic present of the post-partition world of an apocalyptic stupor. Ghatak himself was a victim of the Partition of India in 1947. He had to leave his homeland for a life in Calcutta where for the rest of his life he could not rip off the label of being a ‘refugee’, which the natives of the ‘West’ Bengal had labelled upon the homeless East Bengal masses. The melancholic longing for the estranged homeland forms the basis of most of Ghatak’s films, especially the trilogy: Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komol Gondhar (1960) and Subarnarekha (1961). Ghatak’s running obsession with the post-partition trauma acts as one of the predominant themes in the plots of his films. To bring out the tragedy of the situation more vividly, he deploys music and melodrama as essential tropes. Ghatak brilliantly juxtaposes different genres of music, from Indian Classical Music and Rabindra Sangeet to folk songs, to carve out the trauma of a soul striving for recognition in a new land while, at the same time, trying hard to cope with the loss of its ‘motherland’.