Project Number: JDF IQP 0712 HEISENBERG and the GERMAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Russian-A(Merican) Bomb: the Role of Espionage in the Soviet Atomic Bomb Project

J. Undergrad. Sci. 3: 103-108 (Summer 1996) History of Science The Russian-A(merican) Bomb: The Role of Espionage in the Soviet Atomic Bomb Project MICHAEL I. SCHWARTZ physicists and project coordinators ought to be analyzed so as to achieve an understanding of the project itself, and given the circumstances and problems of the project, just how Introduction successful those scientists could have been. Third and fi- nally, the role that espionage played will be analyzed, in- There was no “Russian” atomic bomb. There only vestigating the various pieces of information handed over was an American one, masterfully discovered by by Soviet spies and its overall usefulness and contribution Soviet spies.”1 to the bomb project. This claim echoes a new theme in Russia regarding Soviet Nuclear Physics—Pre-World War II the Soviet atomic bomb project that has arisen since the democratic revolution of the 1990s. The release of the KGB As aforementioned, Paul Josephson believes that by (Commissariat for State Security) documents regarding the the eve of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, Soviet sci- role that espionage played in the Soviet atomic bomb project entists had the technical capability to embark upon an atom- has raised new questions about one of the most remark- ics weapons program. He cites the significant contributions able and rapid scientific developments in history. Despite made by Soviet physicists to the growing international study both the advanced state of Soviet nuclear physics in the of the nucleus, including the 1932 splitting of the lithium atom years leading up to World War II and reported scientific by proton bombardment,7 Igor Kurchatov’s 1935 discovery achievements of the actual Soviet atomic bomb project, of the isomerism of artificially radioactive atoms, and the strong evidence will be provided that suggests that the So- fact that L. -

Chapter 6 the Aftermath of the Cambridge-Vienna Controversy: Radioactivity and Politics in Vienna in the 1930S

Trafficking Materials and Maria Rentetzi Gendered Experimental Practices Chapter 6 The Aftermath of the Cambridge-Vienna Controversy: Radioactivity and Politics in Vienna in the 1930s Consequences of the Cambridge-Vienna episode ranged from the entrance of other 1 research centers into the field as the study of the atomic nucleus became a promising area of scientific investigation to the development of new experimental methods. As Jeff Hughes describes, three key groups turned to the study of atomic nucleus. Gerhard Hoffman and his student Heinz Pose studied artificial disintegration at the Physics Institute of the University of Halle using a polonium source sent by Meyer.1 In Paris, Maurice de Broglie turned his well-equipped laboratory for x-ray research into a center for radioactivity studies and Madame Curie started to accumulate polonium for research on artificial disintegration. The need to replace the scintillation counters with a more reliable technique also 2 led to the extensive use of the cloud chamber in Cambridge.2 Simultaneously, the development of electric counting methods for measuring alpha particles in Rutherford's laboratory secured quantitative investigations and prompted Stetter and Schmidt from the Vienna Institute to focus on the valve amplifier technique.3 Essential for the work in both the Cambridge and the Vienna laboratories was the use of polonium as a strong source of alpha particles for those methods as an alternative to the scintillation technique. Besides serving as a place for scientific production, the laboratory was definitely 3 also a space for work where tasks were labeled as skilled and unskilled and positions were divided to those paid monthly and those supported by grant money or by research fellowships. -

Bibliography Physics and Human Rights Michele Irwin and Juan C Gallardo August 18, 2017

Bibliography Physics and Human Rights Michele Irwin and Juan C Gallardo August 18, 2017 Physicists have been actively involved in the defense of Human Rights of colleague physicists, and scientists in general, around the world for a long time. What follows is a list of talks, articles and informed remembrances on Physics and Human Rights by physicist-activists that are available online. The selection is not exhaustive, on the contrary it just reflects our personal knowledge of recent publications; nevertheless, they are in our view representative of the indefatigable work of a large number of scientists affirming Human Rights and in defense of persecuted, in prison or at risk colleagues throughout the world. • “Ideas and Opinions” Albert Einstein Crown Publishers, 1954, 1982 The most definitive collection of Albert Einstein's writings, gathered under the supervision of Einstein himself. The selections range from his earliest days as a theoretical physicist to his death in 1955; from such subjects as relativity, nuclear war or peace, and religion and science, to human rights, economics, and government. • “Physics and Human Rights: Reflections on the past and the present” Joel L. Lebowitz Physikalische Blatter, Vol 56, issue 7-8, pages 51-54, July/August 2000 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/phbl.20000560712/pdf Based loosely on the Max von Laue lecture given at the German Physical Society's annual meeting in Dresden, 03/2000. This article focus on the moral and social responsibilities of scientists then -Nazi period in Germany- and now. Max von Laue's principled moral response at the time, distinguished him from many of his contemporary scientists. -

Alfred O. C. Nier

CHEMICAL HERITAGE FOUNDATION ALFRED O. C. NIER Transcript of Interviews Conducted by Michael A. Grayson and Thomas Krick at University of Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota on 7, 8, 9, and 10 April 1989 (With Subsequent Corrections and Additions) ACKNOWLEDGMENT This oral history is one in a series initiated by the Chemical Heritage Foundation on behalf of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. The series documents the personal perspectives of individuals related to the advancement of mass spectrometric instrumentation, and records the human dimensions of the growth of mass spectrometry in academic, industrial, and governmental laboratories during the twentieth century. This project is made possible through the generous support of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry Upon Alfred O.C. Nier’s death in 1994, this oral history was designated Free Access. Please note: Users citing this interview for purposes of publication are obliged under the terms of the Chemical Heritage Foundation Oral History Program to credit CHF using the format below: Alfred O.C. Nier, interview by Michael A. Grayson and Thomas Krick at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 7-10 April 1989 (Philadelphia: Chemical Heritage Foundation, Oral History Transcript # 0112). Chemical Heritage Foundation Oral History Program 315 Chestnut Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19106 The Chemical Heritage Foundation (CHF) serves the community of the chemical and molecular sciences, and the wider public, by treasuring the past, educating the present, and inspiring the future. CHF maintains a world-class collection of materials that document the history and heritage of the chemical and molecular sciences, technologies, and industries; encourages research in CHF collections; and carries out a program of outreach and interpretation in order to advance an understanding of the role of the chemical and molecular sciences, technologies, and industries in shaping society. -

Jagd Auf Die Klügsten Köpfe

1 DEUTSCHLANDFUNK Redaktion Hintergrund Kultur / Hörspiel Redaktion: Ulrike Bajohr Dossier Jagd auf die klügsten Köpfe. Intellektuelle Zwangsarbeit deutscher Wissenschaftler in der Sowjetunion. Ein Feature von Agnes Steinbauer 12:30-13:15 Sprecherin: An- und Absage/Text: Edda Fischer 13:10-13:45 Sprecher 1: Zitate, Biografien Thomas Lang Sprecher 2: An- und Absage/Zwischentitel/ ov russisch: Lars Schmidtke (HSP) Produktion: 01. /02 August 2011 ab 12:30 Studio: H 8.1 Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Die Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in §§ 44a bis 63a Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig. © - unkorrigiertes Exemplar - Sendung: Freitag, d. 05.August 2011, 19.15 – 2 01aFilmton russisches Fernsehen) Beginn bei ca 15“... Peenemünde.... Wernher von Braun.... nach ca 12“(10“) verblenden mit Filmton 03a 03a 0-Ton Boris Tschertok (russ./ Sprecher 2OV ) Im Oktober 1946 wurde beschlossen, über Nacht gleichzeitig alle nützlichen deutschen Mitarbeiter mit ihren Familien und allem, was sie mitnehmen wollten, in die UdSSR zu transportieren, unabhängig von ihrem Einverständnis. Filmton 01a hoch auf Stichwort: Hitler....V2 ... bolschoi zaschtschitny zel darauf: 03 0-Ton Karlsch (Wirtschaftshistoriker): 15“ So können wir sagen, dass bis zu 90 Prozent der Wissenschaftler und Ingenieure, die in die Sowjetunion kamen, nicht freiwillig dort waren, sondern sie hatten keine Chance dem sowjetischen Anliegen auszuweichen. Filmton 01a bei Detonation hoch und weg Ansage: Jagd auf die klügsten Köpfe. Intellektuelle Zwangsarbeit deutscher Wissenschaftler in der Sowjetunion. Ein Feature von Agnes Steinbauer 3 04 0-Ton Helmut Wolff 57“ Am 22.Oktober frühmorgens um vier klopfte es recht heftig an die Tür, und vor der Wohnungstür stand ein sowjetischer Offizier mit Dolmetscherin, rechts und links begleitet von zwei sowjetischen Soldaten mit MPs im Anschlag. -

Der Mythos Der Deutschen Atombombe

Langsame oder schnelle Neutronen? Der Mythos der deutschen Atombombe Prof. Dr. Manfred Popp Karlsruher Institut für Technologie Ringvorlesung zum Gedächtnis an Lise Meitner Freie Universität Berlin 29. Oktober 2018 In diesem Beitrag geht es zwar um Arbeiten zur Kernphysik in Deutschland während des 2.Weltkrieges, an denen Lise Meitner wegen ihrer Emigration 1938 nicht teilnahm. Es geht aber um das Thema Kernspaltung, zu dessen Verständnis sie wesentliches beigetragen hat, um die Arbeit vieler, gut vertrauter, ehemaliger Kollegen und letztlich um das Schicksal der deutschen Physik unter den Nationalsozialisten, die ihre geistige Heimat gewesen war. Da sie nach dem Abwurf der Bombe auf Hiroshima auch als „Mutter der Atombombe“ diffamiert wurde, ist es ihr gewiss nicht gleichgültig gewesen, wie ihr langjähriger Partner und Freund Otto Hahn und seine Kollegen während des Krieges mit dem Problem der möglichen Atombombe umgegangen sind. 1. Stand der Geschichtsschreibung Die Geschichtsschreibung über das deutsche Uranprojekt 1939-1945 ist eine Domäne amerikanischer und britischer Historiker. Für die deutschen Geschichtsforscher hatte eines der wenigen im Ergebnis harmlosen Kapitel der Geschichte des 3. Reiches keine Priorität. Unter den alliierten Historikern hat sich Mark Walker seit seiner Dissertation1 durchgesetzt. Sein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Kaiser Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im 3. Reich beginnt mit den Worten: „The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics is best known as the place where Werner Heisenberg worked on nuclear weapons for Hitler.“2 Im Jahr 2016 habe ich zum ersten Mal belegt, dass diese Schlussfolgerung auf Fehlinterpretationen der Dokumente und auf dem Ignorieren physikalischer Fakten beruht.3 Seit Walker gilt: Nicht an fehlenden Kenntnissen sei die deutsche Atombombe gescheitert, sondern nur an den ökonomischen Engpässen der deutschen Kriegswirtschaft: „An eine Bombenentwicklung wäre [...] auch bei voller Unterstützung des Regimes nicht zu denken gewesen. -

On the Planck-Einstein Relation Peter L

On the Planck-Einstein Relation Peter L. Ward US Geological Survey retired Science Is Never Settled PO Box 4875, Jackson, WY 83001 [email protected] Abstract The Planck-Einstein relation (E=hν), a formula integral to quantum mechanics, says that a quantum of energy (E), commonly thought of as a photon, is equal to the Planck constant (h) times a frequency of oscillation of an atomic oscillator (ν, the Greek letter nu). Yet frequency is not quantized—frequency of electromagnetic radiation is well known in Nature to be a continuum extending over at least 18 orders of magnitude from extremely low frequency (low-energy) radio signals to extremely high-frequency (high-energy) gamma rays. Therefore, electromagnetic energy (E), which simply equals a scaling constant times a continuum, must also be a continuum. We must conclude, therefore, that electromagnetic energy is not quantized at the microscopic level as widely assumed. Secondly, it makes no physical sense in Nature to add frequencies of electromagnetic radiation together in air or space—red light plus blue light does not equal ultraviolet light. Therefore, if E=hν, then it makes no physical sense to add together electromagnetic energies that are commonly thought of as photons. The purpose of this paper is to look at the history of E=hν and to examine the implications of accepting E=hν as a valid description of physical reality. Recognizing the role of E=hν makes the fundamental physics studied by quantum mechanics both physically intuitive and deterministic. Introduction On Sunday, October 7, 1900, Heinrich Rubens and wife visited Max Planck and wife for afternoon tea (Hoffmann, 2001). -

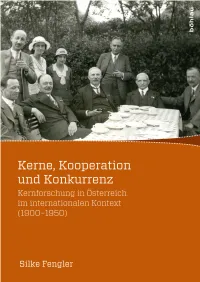

Kerne, Kooperation Und Konkurrenz. Kernforschung In

Wissenschaft, Macht und Kultur in der modernen Geschichte Herausgegeben von Mitchell G. Ash und Carola Sachse Band 3 Silke Fengler Kerne, Kooperation und Konkurrenz Kernforschung in Österreich im internationalen Kontext (1900–1950) 2014 Böhlau Verlag Wien Köln Weimar The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) : P 19557-G08 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Datensind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung: Zusammentreffen in Hohenholte bei Münster am 18. Mai 1932 anlässlich der 37. Hauptversammlung der deutschen Bunsengesellschaft für angewandte physikalische Chemie in Münster (16. bis 19. Mai 1932). Von links nach rechts: James Chadwick, Georg von Hevesy, Hans Geiger, Lili Geiger, Lise Meitner, Ernest Rutherford, Otto Hahn, Stefan Meyer, Karl Przibram. © Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik, Wien © 2014 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H & Co. KG, Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Lektorat: Ina Heumann Korrektorat: Michael Supanz Umschlaggestaltung: Michael Haderer, Wien Satz: Michael Rauscher, Wien Druck und Bindung: Prime Rate kft., Budapest Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefrei gebleichtem Papier Printed in Hungary ISBN 978-3-205-79512-4 Inhalt 1. Kernforschung in Österreich im Spannungsfeld von internationaler Kooperation und Konkurrenz ....................... 9 1.1 Internationalisierungsprozesse in der Radioaktivitäts- und Kernforschung : Eine Skizze ...................... 9 1.2 Begriffsklärung und Fragestellungen ................. 10 1.2.2 Ressourcenausstattung und Ressourcenverteilung ......... 12 1.2.3 Zentrum und Peripherie ..................... 14 1.3 Forschungsstand ........................... 16 1.4 Quellenlage ............................. -

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Werner Heisenberg And

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science PREPRINT 203 (2002) Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project Otto Hahn and the Declarations of Mainau and Göttingen Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project* Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg’s (1901-1976) involvement in the German Uranium Project is the most con- troversial aspect of his life. The controversial discussions on it go from whether Germany at all wanted to built an atomic weapon or only an energy supplying machine (the last only for civil purposes or also for military use for instance in submarines), whether the scientists wanted to support or to thwart such efforts, whether Heisenberg and the others did really understand the mechanisms of an atomic bomb or not, and so on. Examples for both extreme positions in this controversy represent the books by Thomas Powers Heisenberg’s War. The Secret History of the German Bomb,1 who builds up him to a resistance fighter, and by Paul L. Rose Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project – A Study in German Culture,2 who characterizes him as a liar, fool and with respect to the bomb as a poor scientist; both books were published in the 1990s. In the first part of my paper I will sum up the main facts, known on the German Uranium Project, and in the second part I will discuss some aspects of the role of Heisenberg and other German scientists, involved in this project. Although there is already written a lot on the German Uranium Project – and the best overview up to now supplies Mark Walker with his book German National Socialism and the quest for nuclear power, which was published in * Paper presented on a conference in Moscow (November 13/14, 2001) at the Institute for the History of Science and Technology [àÌÒÚËÚÛÚ ËÒÚÓËË ÂÒÚÂÒÚ‚ÓÁ̇ÌËfl Ë ÚÂıÌËÍË ËÏ. -

Stalin and the Atomic Bomb 51

50 Stalin and the The beginning of the uranium problem Amongst physicists, and in many books on the Atomic Bomb history of atomic energy in the USSR, the code name Uran*, in Russian, chosen by Stalin in September 1942 as the specified designation of the Stalingrad counter-attack, is linked with the element uranium. They presume that Stalin, having at this time already approved the setting up of investigations into the uranium problem, found himself under the influence of the potential explosive force of the nuclear bomb. The physicists, however, are mistaken. The codename for the Stalingrad operation was Zhores A. Medvedev chosen by Stalin in honour of Uranus, the seventh planet of the solar system. The strategic battle following ‘Uranus’ – the encirclement and rout of the German armies in the region of Rostov on Don – was given the codename ‘Saturn’ by Stalin. The first mention in the Soviet press of the unusual explosive force of the atomic bomb appeared in Pravda on 13th October 1941. Publishing a report about an anti-fascist meeting of scholars in Moscow the previous day, the paper described to the astonished This article was published reader the testimony of academician Pyotr in Russia on the 120th Leonidovich Kapitsa. anniversary of Stalin’s birth ‘... Explosive materials are one of the basic on 21 December 1879. The weapons of war... But recent years have opened first Soviet atomic bomb up new possibilities – the use of atomic energy. was exploded on 29 August Theoretical calculations show that if a 1949. contemporary powerful bomb can, for example, destroy an entire quarter of a town, then an atomic bomb, even a fairly small one, if it is Zhores A. -

03 Dossier Karin Zachmannl.Indd

Peaceful atoms in agriculture and food: how the politics of the Cold War shaped agricultural research using isotopes and radiation in post war divided Germany Karin Zachmann (*) (*) orcid.org/0000-0001-5533-2211. Technische Universität München. [email protected] Dynamis Fecha de recepción: 30 de junio de 2014 [0211-9536] 2015; 35 (2): 307-331 Fecha de aceptación: 7 de abril de 2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0211-95362015000200003 SUMMARY: 1.—Introduction. 2.—Early research prior to the Cold War. 3.—Legal and material provisions: research as subject of allied power politics. 4.—West German research before 1955: resumptions of prewar efforts and new starts under allied control. 5.—The East German (re-) entry into nuclear research since 1955: Soviet assistance, new institutions and conflicting expectations. 6.—State fostered research in West Germany: launching the Atomic Research Program of the Federal Ministry of Agriculture. 7.—Conclusion. ABSTRACT: During the Cold War, the super powers advanced nuclear literacy and access to nuclear resources and technology to a first-class power factor. Both national governments and international organizations developed nuclear programs in a variety of areas and promoted the development of nuclear applications in new environments. Research into the use of isoto- pes and radiation in agriculture, food production, and storage gained major importance as governments tried to promote the possibility of a peaceful use of atomic energy. This study is situated in divided Germany as the intersection of the competing socio-political systems and focuses on the period of the late 1940s and 1950s. It is argued that political interests and international power relations decisively shaped the development of «nuclear agriculture». -

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: a Study in German Culture

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project http://content.cdlib.org/xtf/view?docId=ft838nb56t&chunk.id=0&doc.v... Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project A Study in German Culture Paul Lawrence Rose UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1998 The Regents of the University of California In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday ― ix ― ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For hospitality during various phases of work on this book I am grateful to Aryeh Dvoretzky, Director of the Institute of Advanced Studies of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, whose invitation there allowed me to begin work on the book while on sabbatical leave from James Cook University of North Queensland, Australia, in 1983; and to those colleagues whose good offices made it possible for me to resume research on the subject while a visiting professor at York University and the University of Toronto, Canada, in 1990–92. Grants from the College of the Liberal Arts and the Institute for the Arts and Humanistic Studies of The Pennsylvania State University enabled me to complete the research and writing of the book.