Civilian Peacekeeping – a Barely Tapped Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Constitutionalism and Japan's Constitutional Pacifism

Global Constitutionalism and Japan’s Constitutional Pacifism(Kimijima) Article Global Constitutionalism and Japan’s Constitutional Pacifism Akihiko Kimijima Abstract The essence of constitutionalism is to regulate the exercise of power and in so doing to constitute liberty. The most critical of these powers to be regulated, and the focus of this article, is military power. The author traces the history of global constitutional thought throughout the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries including the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Also covered are successful practices of regulating and replacing military power by civil society in the 1990s and the 2000s. The article also discusses Article 9, the “pacifist” clause of the 1946 Constitution of Japan, as a notable example of the regulation of military power; its trajectory is full of contention, compromise, and undeveloped possibilities. Finally this article emphasizes that Article 9 has been̶and will continue to be̶quoted by the counter-hegemonic global civil society in its efforts to regulate military power. INTRODUCTION 1) It is noteworthy that discussions of global constitutionalism have become very active in recent years. The Japanese academia is no exception (Urata 2005; Mogami 2007; Kimijima 2009). Caution is required, however, because various authors use the term and concept differently. There are several different kinds of global constitutionalism. My own understanding will be discussed further later in this article, but perhaps it is helpful to mention some of its elements here. I use the terms “constitution” and “constitutionalism” in a broader sense. Constitution is a set of fundamental principles for regulating power in a given political community, and constitutionalism is a project to regulate the exercise of power by rules, laws, and institutions. -

Examining Unarmed Civilian Protection in the UN Context: a Complement and Contribution to POC

Examining Unarmed Civilian Protection in the UN Context: A Complement and Contribution to POC Consultation for Member States: 10 – 11 May 2019, Tarrytown, New York On 10-11 May 2019, the Permanent Missions to the United Nations of Australia, Senegal and Uruguay along with the NGO Nonviolent Peaceforce hosted a retreat for representatives of member states, the UN Secretariat and several NGOs to examine unarmed civilian protection (UCP) methods and possible contributions to the UN’s work on the protection of civilians. Over the course of 1.5 days, participants were introduced to the concept of UCP and discussed the practical work of Nonviolent Peaceforce in different countries and settings, as well as various related topics: UCP with refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs); community engagement in peacekeeping: integrating local protection and self-protection approaches; UCP and DPO field missions; UCP and the role of UN Member States; and integrating high-level and local approaches to negotiation and mediation. Civilians have increasingly become victims of the wars and violent conflicts that plague so many parts of the world today. The methods and philosophy of unarmed civilian protection can help break these cycles of violence and contribute to the spectrum of tools used by the international community to protect civilians and prevent violence. 1 Nonviolent Peaceforce (NP) and at least 40 other NGOs1 prevent violence, protect civilians and promote peace through unarmed civilian protection (UCP). UCP represents a philosophical change in POC that emphasizes protection from the bottom up, community ownership and deep, sustained engagement with the communities served. UCP is a comprehensive approach that offers a unique combination of methods that have been shown to protect civilians in violent conflicts. -

'Art of a Second Order': the First World War from the British Home Front Perspective

‘ART OF A SECOND ORDER’ The First World War From The British Home Front Perspective by RICHENDA M. ROBERTS A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Little art-historical scholarship has been dedicated to fine art responding to the British home front during the First World War. Within pre-war British society concepts of sexual difference functioned to promote masculine authority. Nevertheless in Britain during wartime enlarged female employment alongside the presence of injured servicemen suggested feminine authority and masculine weakness, thereby temporarily destabilizing pre-war values. Adopting a socio-historical perspective, this thesis argues that artworks engaging with the home front have been largely excluded from art history because of partiality shown towards masculine authority within the matrices of British society. Furthermore, this situation has been supported by the writing of art history, which has, arguably, followed similar premise. -

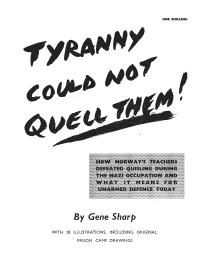

Tyranny Could Not Quell Them

ONE SHILLING , By Gene Sharp WITH 28 ILLUSTRATIONS , INCLUDING PRISON CAM ORIGINAL p DRAWINGS This pamphlet is issued by FOREWORD The Publications Committee of by Sigrid Lund ENE SHARP'S Peace News articles about the teachers' resistance in Norway are correct and G well-balanced, not exaggerating the heroism of the people involved, but showing them as quite human, and sometimes very uncertain in their reactions. They also give a right picture of the fact that the Norwegians were not pacifists and did not act out of a sure con viction about the way they had to go. Things hap pened in the way that they did because no other wa_v was open. On the other hand, when people acted, they The International Pacifist Weekly were steadfast and certain. Editorial and Publishing office: The fact that Quisling himself publicly stated that 3 Blackstock Road, London, N.4. the teachers' action had destroyed his plans is true, Tel: STAmford Hill 2262 and meant very much for further moves in the same Distribution office for U.S.A.: direction afterwards. 20 S. Twelfth Street, Philadelphia 7, Pa. The action of the parents, only briefly mentioned in this pamphlet, had a very important influence. It IF YOU BELIEVE IN reached almost every home in the country and every FREEDOM, JUSTICE one reacted spontaneously to it. AND PEACE INTRODUCTION you should regularly HE Norwegian teachers' resistance is one of the read this stimulating most widely known incidents of the Nazi occu paper T pation of Norway. There is much tender feeling concerning it, not because it shows outstanding heroism Special postal ofler or particularly dramatic event§, but because it shows to new reuders what happens where a section of ordinary citizens, very few of whom aspire to be heroes or pioneers of 8 ~e~~ 2s . -

The Commune Movement During the 1960S and the 1970S in Britain, Denmark and The

The Commune Movement during the 1960s and the 1970s in Britain, Denmark and the United States Sangdon Lee Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2016 i The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement ⓒ 2016 The University of Leeds and Sangdon Lee The right of Sangdon Lee to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 ii Abstract The communal revival that began in the mid-1960s developed into a new mode of activism, ‘communal activism’ or the ‘commune movement’, forming its own politics, lifestyle and ideology. Communal activism spread and flourished until the mid-1970s in many parts of the world. To analyse this global phenomenon, this thesis explores the similarities and differences between the commune movements of Denmark, UK and the US. By examining the motivations for the communal revival, links with 1960s radicalism, communes’ praxis and outward-facing activities, and the crisis within the commune movement and responses to it, this thesis places communal activism within the context of wider social movements for social change. Challenging existing interpretations which have understood the communal revival as an alternative living experiment to the nuclear family, or as a smaller part of the counter-culture, this thesis argues that the commune participants created varied and new experiments for a total revolution against the prevailing social order and its dominant values and institutions, including the patriarchal family and capitalism. -

A3299-B8-1-2-001-Jpeg.Pdf

G> ) vl Recording made by Hilda Bernstein, 1j5th March 1973, on her recollections of the South African Peace Movement. I think there were two very important reasons why we started a Peace Movement - at least I was involved with these two reasons The first was a desire to do something about the menacing world situation since the dropping of the nuclear bombs in Japan, to outlaw nuclear weapons and to save the potential world from this terriDleXdisaster it was facing; and the second was the desire to link up any activities on this front in South Africa with some sort of international movement, particularly in South Africa because one is so terribly isolated there from world affairs. This was in the early 1950's, a kind of post-war activity which grew up: people who took an active part in politics in South Africa also of course followed what was happening overseas, inter national affairs as we called it, but a lot of South Africans are very much absorbed with their own problems which are real and near, and everything else seems so far away and nobody cares a damn about it. We felt a necessity to establish this international link. Now during the whole time of its existence the official peace movement in South Africa wasn't officially connected with the World Peace Council, but this was for safety reasons as far as the South African Government was concerned. But unofficially we kept our links with them, and wherever we could we sent people to conferences that were held. -

Peace Initiatives in Colombia

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Nearly half-a-century old, the Colombian conflict has spawned a Virginia M. Bouvier long tradition of peace initiatives that offer innovative alternatives to violence. Peace Initiatives in Colombia, a conference sponsored by the United States Institute of Peace and the Latin American Studies Program at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, November 19–20, 2005, analyzed these initiatives from various perspectives and Harbingers of Hope identified the variables and strategies relevant to their success. The conference brought together contributors to a book on Colombian peace initiatives being edited by Virginia M. Bouvier, a Latin American Peace Initiatives in Colombia specialist and senior program officer of the Jennings Randolph Program at the U.S. Institute of Peace. Conference speakers included some twenty individuals from a broad range of academic fields, as well as human rights and development specialists, photographers, Summary and political and military analysts from Colombia, the United States, and Europe. A list of conference participants, about half of whom are • With the reelection of incumbent President Alvaro Uribe on May 28, 2006, a “ripe current or former USIP grantees or peace scholars, is at the end of moment” may be emerging for resolving Colombia’s long-standing armed conflict. this report. After exerting pressure on the guerrillas and demobilizing the largest paramilitary The conference was organized by Dr. Bouvier and Dr. Mary Roldán. organization during his first term, President Uribe is well positioned to pursue a Additional sponsors included Cornell’s Africana Studies and Research political solution to the conflict. -

Download the Newsletter

P.E.A.C.E. News for January 2021 Peace Educators Allied for Children Everywhere, Inc. (P.E.A.C.E., Inc.) Please contribute to our future as we support the peaceful world we and the children need to thrive. • Donate Now • Please keep using your mask, with social distancing & hand washing, until we’re all safe again. ACTION ALERTS! DEY Guidelines for Talking with Young Children About the Insurrection at the US Capitol On January 6, the world witnessed an unprecedented assault on democracy when a violent mob, incited by President Trump, invaded the Capitol building in Washington, DC to disrupt the certification of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris as the next President and Vice-President of the United States. Threatening the safety of members of Congress, Hill staff, and the Capitol’s everyday working people, all trapped inside and terrorized while this mob ransacked the People’s Building. Watching this unfold was shocking to many adults and, despite their best efforts to shield young children from this reality, they may have been exposed to this despicable event anyway, whether through the media, siblings, friends, or overhear-ing adults’ conversations. This can undermine their sense of safety as well as their social and emotional well-being. While young children are not able to comprehend complicated concepts like an attack on our democracy or the meaning of an attempt-ed coup, they will undoubtedly be frightened and confused by the violent images of the mob as well as the deep and obvious concerns of the adults around them. Defending the Early Years (DEY) offers guidelines for implementing an age-appropriate, meaningful, and caring approach to help young children deal with this shocking event: ● Protect young children from exposure to news on TV, radio, social media, or hearing adults talk about it as much as possible. -

Unit V 1. India As a Champion of World Peace and Justice A

UNIT V 1. INDIA AS A CHAMPION OF WORLD PEACE AND JUSTICE A peace movement is a social movement that seeks to achieve ideals such as the ending of a particular war (or all wars), minimize inter-human violence in a particular place or type of situation, and is often linked to the goal of achieving world peace. Means to achieve these ends include advocacy of pacifism, non-violent resistance, diplomacy, boycotts, peace camps, moral purchasing, supporting anti-war political candidates, legislation to remove the profit from government contracts to the Military–industrial complex, banning guns, creating open government and transparency tools, direct democracy, supporting Whistleblowers who expose War-Crimes or conspiracies to create wars, demonstrations, and national political lobbying groups to create legislation. The political cooperative is an example of an organization that seeks to merge all peace movement organizations and green organizations, which may have some diverse goals, but all of whom have the common goal of peace and humane sustainability. A concern of some peace activists is the challenge of attaining peace when those that oppose it often use violence as their means of communication and empowerment. Some people refer to the global loose affiliation of activists and political interests as having a shared purpose and this constituting a single movement, "the peace movement", an all encompassing "anti-war movement". Seen this way, the two are often indistinguishable and constitute a loose, responsive, event-driven collaboration between groups with motivations as diverse as humanism, environmentalism, veganism, anti- racism, feminism, decentralization, hospitality, ideology, theology, and faith. There are different ideas over what "peace" is (or should be), which results in a plurality of movements seeking diverse ideals of peace. -

2014 Performance Report

2014 PERFORMANCE REPORT 1 | HUMANITY UNITED | 2014 PERFORMANCE REPORT PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Dear friends, Every year as we prepare this report and I reflect back on our worked since 2008 — that has upended a nation that once held work, I am reminded of what a great privilege it is to work with much promise and seen the death and displacement of far too Humanity United’s partners, leaders, and staff — people so many of its people. Similarly, Humanity United has worked for dedicated to a more peaceful and free world. Though we focus the past seven years in Liberia, where the world watched the on some of the most intractable problems facing humanity, I agonizing devastation of the Ebola epidemic ravage the people am proud of the shared spirit we collectively bring to this work. of this fragile state with unexpected speed. 2014 was a year of much hope on many fronts and a year of In these cases, we supported and witnessed the heroic work despair on others. It was a powerful reminder that our vision of of partners like Nonviolent Peaceforce, Last Mile Health, and a world free of conflict takes resilience, creativity, hard work, Doctors Without Borders, who were on the front lines of these and an unwavering dedication to sustainable social change. tragedies. We also resolved to do more to help these people It also sometimes takes renewal. That is why we dedicated so who have for too long been deprived of the peace, security, much time this year trying to more fully understand how we and freedom that they deserve. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Michael Gove, 15 November 2010, Hansard Parliamentary Debates,column 634, www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011. 2. Ofsted made a statement to this effect on 11 July 2004 which was reported on by the BBC (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/3884087.stm) and The Telegraph (www.telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews). 3. There is a growing literature on the Falklands War, most of which does not contextualise the conflict in terms of the British Empire despite the jingoistic use of imperial ideology during the conflict. 4. Bill Schwarz (2011) The White Man’s World, Memories of Empire, 1 (Oxford University Press), p. 6. 5. Avner Offer (1993) ‘The British Empire, 1870–1914: A Waste of Money?’, The Economic History Review 46, no. 2, 215–38. 6. Bernard Porter (2004) The Absent-Minded Imperialists: Empire, Society, and Culture in Britain (Oxford University Press); John M. MacKenzie (1984) Pro- paganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion, 1880–1960 (Manchester University Press). 7. Alan Sked (1987) Britain’s Decline: Problems and Perspectives (Oxford: Basil Blackwell). 8. Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose (2006) ‘Introduction: Being at Home with the Empire’, in Catherine Hall and Sonya O. Rose (eds), At Home with the Empire: Metropolitan Culture and the Imperial World (Cambridge University Press). 9. Bill Schwarz (1996) ‘ “The Only White Man in There”: The Re-Racialisation of England, 1956–1968’, Race and Class 38, no. 1, 65. 10. Stuart Ward (ed.) (2001) British Culture and the End of Empire,Studiesin Imperialism (Manchester University Press). 11. Stuart Ward (2001) ‘Introduction’, in idem (ed.), British Culture and the End of Empire (Manchester University Press), p. -

The Peace Journalist

IN THIS ISSUE • PJ project in Northern Ireland • Dispatches from South Korea, Cameroon, Uganda, Ghana • Jake Lynch: 20 years of peacebuilding media At Park University, discussing Peace Journalism with Prof. Raj Gandhi A publication of the Center for Global Peace Journalism at Park University Vol 8 No. 2 - October 2019 October 2019 October 2019 Contents 3 Gandhi at Park U. 14 U.S. Was Gandhi a peace journalist? Filmmaker meets “The Enemy” Cover photos-- Left and top right by Phyllis Gabauer Park Univ. 16 Worldwide peace stud- The Peace Journalist is a semi- Lynch: 20 yrs of peace media ies student annual publication of the Center Alyssa Williams for Global Peace Journalism at Park 18 South Korea discusses the University in Parkville, Missouri. The Journalists gather to discuss PJ elements of Peace Journalist is dedicated to dis- peace with Prof. seminating news and information 19 Ghana Raj Gandhi. for teachers, students, and Radio as a change agent practitioners of PJ. 6 Gandhi, Hate speech 20 Kashmir Submissions are welcome from all. Gandhian principles combat hate We are seeking shorter submissions Outlet gives voice to youth (300-500 words) detailing peace S. Sudan-Uganda journalism projects, classes, propos- 8 21 Cameroon als, etc. We also welcome longer Network connects communities PJ prize;Community media Prof. Gandhi enlightens Park University submissions (800-1200 words) By Steven Youngblood of our opponents.” Indian Opinion journal, Gandhi said, “I about peace or conflict sensitive 10 Northern Ireland 22 South Sudan When asked to describe Mahatma cannot recall a word in those articles journalism projects or programs, as Project energizes journalists Govmt.