Melina Marchetta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saving Francesca

TEACHERS ’ RESOURCES RECOMMENDED FOR Upper secondary Ages 14+; years 9 to 12 CONTENTS 1. Plot summary 1 2. About the author 2 3. About the book 2 4. Mode of telling 2 5. Key themes and study topics 3–8 6. Further reading 8–9 KEY CURRICULUM AREAS Learning areas: English General capabilities: Language, Literature, Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability REASONS FOR STUDYING THIS BOOK To analyse how language and writing evoke mood, tone and character To discuss what makes a story and its characters extraordinary and fully realised To discuss identity and self-actualisation To discuss gender difference and what Saving Francesca feminism means today; to contrast this with feminism’s origins and the changing role of girls Melina Marchetta and women To encourage creative and imaginative writing To discuss resilience and mental health PLOT SUMMARY Francesca is at the beginning of her second term in THEMES Year Eleven at an all boy’s school that has just started Identity accepting girls. She misses her old friends, and, to Friendship make things worse, her mother has had a breakdown Family Feminism and can barely move from her bed. Humour But Francesca had not counted on the fierce loyalty of Mental health her new friends, or falling in love, or finding that it’s Memory within her to bring her family back together. PREPARED BY A memorable and much-loved Australian classic Penguin Random House Australia and Judith Ridge filled with humour, compassion and joy, from the internationally bestselling and multi-award-winning PUBLICATION DETAILS author of Looking for Alibrandi. -

Ysd Ar 2010-11

Delaware Library Association Youth Services Division Annual Report to the DLA President, 2010 – 2011 The Children’s Services Division has been active for the year 2010 – 2011, especially with the Delaware Blue Hen Children’s Choice Book Award, which the division sponsors, and the Summer Reading Club in which all public libraries and the Dover Air Force base library participate. The officers for the division for this year have been: Maureen Miller, Lewes Public Library, President Audrey Avery, Dover Public Library, Vice President Sherri Scott, Georgetown Public Library, Secretary-Treasurer Activities of the division include: 1. The Summer Reading Club theme for 2010 was “Make a Splash at Your Library”. The statistics (with 35 libraries reporting) were: Registration = 14,195 (13,147 children, 1048 teens) Completions = 8,038 (7482 children, 556 teens) Percentage of Completions = 56% 2. The 2011 Delaware Blue Hen Children’s Choice Book Awards were voted on by the children of Delaware . The winners were: Picture Book: Tiger Pups by Tom and Allie Harvey Chapter Book: A Season of Gifts by Richard Peck Teen Book: If I Stay by Gayle Forman 3. The 2012 Delaware Blue Hen Children’s Choice Book Award nominees were selected by the youth service award committees. The voting will take place from March 1 to September 31, 2011. The ballots are attached. The winners will be announced on the first Saturday in November 7, 2011, in each public library in the state, along with the official press release. The nominees are as follows: Early Readers: Chalk by -

Talking Books for Children – Ausgewählte Untersuchungen Zum Hörbuchangebot Für Kinder in Australien

Talking books for children – Ausgewählte Untersuchungen zum Hörbuchangebot für Kinder in Australien Diplomarbeit im Fach Kinder- und Jugendmedien Studiengang Öffentliche Bibliotheken der Fachhochschule Stuttgart – Hochschule der Medien Daniela Kies Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr. Horst Heidtmann Zweitprüfer: Prof. Dr. Manfred Nagl Bearbeitungszeitraum: 15. Juli 2002 bis 15. Oktober 2002 Stuttgart, Oktober 2002 Kurzfassung 2 Kurzfassung Gegenstand der hier vorgestellten Arbeit ist das Hörbuchangebot für Kinder in Austra- lien. Seit Jahren haben Gesellschaften für Blinde Tonträger für die eigenen Bibliothe- ken produziert, um blinden oder sehbehinderten Menschen zu helfen. Hörmedien von kommerziellen Produzenten, in Australien ist ABC Enterprises der größte, sind in der Regel gekürzte Versionen von Büchern. Bolinda Audio arbeitet kommerziell, veröffent- licht aber nur ungekürzte Versionen. Louis Braille Audio und VoyalEyes sind Abteilun- gen von Organisationen für Blinde, die Tonträger auch an Bibliotheken verkaufen und sie sind auch im Handel erhältlich. Grundsätzlich gelten öffentliche Bibliotheken als Hauptzielgruppe und ihnen werden spezielle Dienstleistungen von den Verlagen selbst oder dem Bibliothekszulieferer angeboten. Die britische und amerikanische Konkurrenz ist im Kindertonträgerbereich besonders groß. Aus diesem Grund spezialisieren sich australische Hörbuchverlage auf die Produktion von Büchern australischer Autoren und/ oder über Australien. Bei Kindern sind die Autoren John Marsden, Paul Jennings und Andy Griffiths sehr beliebt. Stig Wemyss, ein ausgebildeter Schauspieler, hat zahl- reiche Bücher bei verschiedenen Verlagen erfolgreich gelesen. Musik bzw. Lieder wer- den auf Hörbüchern nur vereinzelt verwendet. Es gibt aber einige Gruppen, z.B. die Wiggles, und Entertainer, z.B. Don Spencer, die Lieder für Kinder schreiben und auf- nehmen. Da der Markt für Kindertonträger in Australien noch im Aufbau ist, lohnt es sich, die Entwicklungen weiter zu verfolgen. -

Printz Award Winners

The White Darkness The First Part Last Teen by Geraldine McCaughrean by Angela Johnson YF McCaughrean YF Johnson 2008. When her uncle takes her on a 2004. Bobby's carefree teenage life dream trip to the Antarctic changes forever when he becomes a wilderness, Sym's obsession with father and must care for his adored Printz Award Captain Oates and the doomed baby daughter. expedition becomes a reality as she is soon in a fight for her life in some of the harshest terrain on the planet. Postcards From No Man's Winners Land American Born Chinese by Aidan Chambers by Gene Luen Yang YF Chambers YGN Yang 2003. Jacob Todd travels to 2007. This graphic novel alternates Amsterdam to honor his grandfather, between three interrelated stories a soldier who died in a nearby town about the problems of young in World War II, while in 1944, a girl Chinese Americans trying to named Geertrui meets an English participate in American popular soldier named Jacob Todd, who culture. must hide with her family. Looking for Alaska A Step From Heaven by John Green by Na An YF Green YF An 2006. 16-year-old Miles' first year at 2002. At age four, Young Ju moves Culver Creek Preparatory School in with her parents from Korea to Alabama includes good friends and Southern California. She has always great pranks, but is defined by the imagined America would be like search for answers about life and heaven: easy, blissful and full of death after a fatal car crash. riches. But when her family arrives, The Michael L. -

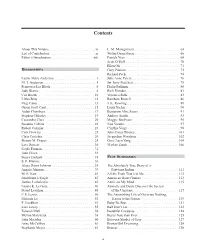

Table of Contents

Contents About This Volume . ix L . M . Montgomery . 64 List of Contributors . xi Walter Dean Myers . 66 Editor’s Introduction . xiii Patrick Ness . 68 Scott O’Dell . 70 Ellen Oh . 71 Biographies Gary Paulsen . 73 Richard Peck . 74 Laurie Halse Anderson . 3 Julie Anne Peters . 76 M . T . Anderson . 4 Sir Terry Pratchett . 78 Francesca Lia Block . 6 Philip Pullman . 80 Judy Blume . 8 Rick Riordan . 81 Coe Booth . 10 Veronica Roth . 83 Libba Bray . 12 Rainbow Rowell . 86 Meg Cabot . 13 J . K . Rowling . 88 Orson Scott Card . 15 Louis Sachar . 90 Aidan Chambers . 17 Benjamin Alire Saenz . 91 Stephen Chbosky . 19 Andrew Smith . 93 Cassandra Clare . 20 Maggie Stiefvater . 95 Suzanne Collins . 22 Ned Vizzini . 97 Robert Cormier . 23 Cynthia Voigt . 98 Cath Crowley . 25 John Corey Whaley . 101 Chris Crutcher . 26 Jacqueline Woodson . 102 Sharon M . Draper . 28 Gene Luen Yang . 104 Lois Duncan . 30 Markus Zusak . 106 Gayle Forman . 31 John Green . 33 Sonya Hartnett . 35 Plot Summaries S . E . Hinton . 36 Alaya Dawn Johnson . 38 The Absolutely True Diary of a Angela Johnson . 39 Part-time Indian . 111 M . E . Kerr . 41 All the Truth That’s in Me . 112 Madeleine L’Engle . 43 American Born Chinese . 113 Justine Larbalestier . 45 Annie on My Mind . 115 Ursula K . Le Guin . 46 Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets David Levithan . 48 of the Universe . 117 C .S . Lewis . 50 The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Malinda Lo . 51 Traitor to the Nation . 119 E . Lockhart . 53 Baby Be-Bop . 121 Lois Lowry . 55 Ball Don’t Lie . -

Printz Award Winners

Jellicoe Road How I Live Now Teen by Melina Marchetta by Meg Rosoff YF Marchetta YF Rosoff 2009. High school student Taylor 2005. To get away from her pregnant Markham, who was abandoned by stepmother in New York City, her drug-addicted mother at the age 15-year-old Daisy goes to England to Printz Award of 11, struggles with her identity and stay with her aunt and cousins, but family history at a boarding school in soon war breaks out and rips the Australia. family apart. Winners The White Darkness The First Part Last by Geraldine McCaughrean by Angela Johnson YF McCaughrean YF Johnson 2008. When her uncle takes her on a 2004. Bobby's carefree teenage life dream trip to the Antarctic changes forever when he becomes a wilderness, Sym's obsession with father and must care for his adored Captain Oates and the doomed baby daughter. expedition becomes a reality as she is soon in a fight for her life in some of the harshest terrain on the planet. Postcards from No Man's Land American Born Chinese by Aidan Chambers by Gene Luen Yang YF Chambers YGN Yang 2003. Jacob Todd travels to 2007. This graphic novel alternates Amsterdam to honor his between three stories about the grandfather, a soldier who died in a problems of young Chinese nearby town in World War II, while in Americans trying to participate in 1944, a girl named Geertrui meets an American popular culture. English soldier named Jacob Todd, who must hide with her family. The Michael L. Printz Award recognizes Looking for Alaska books that exemplify literary A Step from Heaven by John Green excellence in young adult literature YF Green by Na An 2006. -

Thayer Academy Middle School Independent Reading Award

Thayer Academy Middle School Independent Reading A ward Winners 2000-2009 The pages that follow include every winner, honor book, and/or finalist for three major annual awards related to young adult fiction during the specified timespan. The books are predominantly fiction, but there are numerous nonfiction selections, as well as several graphic novels and books of poetry. This document is structured for casual browsing; there’s something for everyone, and simply looking around will help you stumble across a high quality book. National Book Award for Young People’s Literature is an award that seeks to recognize the best of American literature, raise the cultural appreciation of great writing, promote the enduring value of reading, and advance the careers of established and emerging writers. The Michael L. Printz Award is an award for a book that exemplifies literary excellence in young adult literature. The award is sponsored by Booklist, a publication of the American Library Association. YALSA's Award for Excellence in Nonfiction honors the best nonfiction book published for young adults (ages 12-18) during a Nov. 1 – Oct. 31 publishing year. Beyond what’s contained in this document, there are many other lists produced by the Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA) that should be of interest. These include Best Fiction for Young Adults, Great Graphic Novels for Teens, Quick Picks for Reluctant Young Adult Readers, and Teens' Top Ten, amongst others. YALSA is an excellent resource worth exploring. -

Story Time: Australian Children's Literature

Story Time: Australian Children’s Literature The National Library of Australia in association with the National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature 22 August 2019–09 February 2020 Exhibition Checklist Australia’s First Children’s Book Charlotte Waring Atkinson (Charlotte Barton) (1797–1867) A Mother’s Offering to Her Children: By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales Sydney: George Evans, Bookseller, 1841 Parliament Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn777812 Charlotte Waring Atkinson (Charlotte Barton) (1797–1867) A Mother’s Offering to Her Children: By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales Sydney: George Evans, Bookseller, 1841 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn777812 Living Knowledge Nora Heysen (1911–2003) Bohrah the Kangaroo 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn1453161 Nora Heysen (1911–2003) Dinewan the Emu 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn1458954 Nora Heysen (1911–2003) They Saw It Being Lifted from the Earth 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn2980282 1 Catherine Stow (K. ‘Katie’ Langloh Parker) (author, 1856–1940) Tommy McRae (illustrator, c.1835–1901) Australian Legendary Tales: Folk-lore of the Noongahburrahs as Told to the Piccaninnies London: David Nutt; Melbourne: Melville, Mullen and Slade, 1896 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn995076 Catherine Stow (K. ‘Katie’ Langloh Parker) (author, 1856–1940) Henrietta Drake-Brockman (selector and editor, 1901–1968) Elizabeth Durack (illustrator, 1915–2000) Australian Legendary Tales Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1953 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn2167373 Catherine Stow (K. -

Award-‐Winning Literature

Award-winning literature The Pulitzer Prize is a U.S. award for achievements in newspaper and online journalism, literature and musical composition. The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and young adult literature. The Man Booker Prize for Fiction is a literary prize awarded each year for the best original full-length novel, written in the English language, by a citizen of the Commonwealth of Nations, Ireland, or Zimbabwe. The National Book Critics Circle Awards are a set of annual American literary awards by the National Book Critics Circle to promote "the finest books and reviews published in English". The Carnegie Medal in Literature, or simply Carnegie Medal, is a British literary award that annually recognizes one outstanding new book for children or young adults. The Michael L. Printz Award is an American Library Association literary award that annually recognizes the "best book written for teens, based entirely on its literary merit". The Guardian Children's Fiction Prize or Guardian Award is a literary award that annually recognizes one fiction book, written for children by a British or Commonwealth author, published in the United Kingdom during the preceding year. FICTION Where Things Come Back by John Corey Whaley, Michael L. Printz Winner 2012 A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan, Pulitzer Prize 2011 Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward, National Book Award 2011 The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes, Man Booker Prize 2011 Ship Breaker by Paolo Baciagalupi, Michael -

Plainsong Or Polyphony?

Plainsong or Polyphony? Australian Award‐Winning Novels of the 1990s for Adolescent Readers. Heather Voskuyl Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2008 Certificate of Authorship / Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of the requirements for a degree. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information resources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Candidate _____________________________________________________ i Acknowledgements I would like to thank two people for the contributions they have made to this thesis, my supervisor Rosemary Ross Johnston for challenging me and encouraging me to persist, and my husband Hans for his patience and support. I would also like to acknowledge the support and encouragement given to me by my employer, Queenwood School for Girls. ii Contents: Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Voice 6 Theoretical Perspectives 10 Adolescent Readers 22 Australian YA Novels 28 Addressing a Dear Child or a Becoming Adult? 35 Chapter 2: Who Speaks? 40 Omniscient Narrators 43 Multiple Narrators 48 Reliable Adolescent Narrator/Protagonists 54 Unreliable Adolescent Narrator/Protagonists 58 An Eclectic Mix? 60 Dangerous Spaces in Between 70 Chapter 3: Who Speaks to Whom? 76 Narratees 77 Subordinate Adolescent Characters – Friends and Foes 92 Chapter -

Independent Reading Contract Trimester 1

1st Trimester Independent Reading Project For the 1st trimester independent reading project, you will need to read a Printz Award or Honor book. When finished, you will choose whether to create a book trailer or a comic strip. The explanations of each are included in this packet. For this project, there are certain requirements. The book you choose: • Must not be made into a movie or tv show/series • Can’t be one you’ve read already • Must be within your reading range (at or above 8th grade level) • You must read it after Sept 4,2019 The Michael L. Printz Award is an award for a book that exemplifies literary excellence in young adult literature. It is named for a Topeka, Kansas school librarian who was a long-time active member of the Young Adult Library Services Association. The award is sponsored by Booklist, a publication of the American Library Association. Learn more about Michael Printz via this video from cjonline.com The following is a list of both Printz Award winning books, as well as Honor books. I may have a few of these, but you will most likely need to scour OV library, local library, or bookstores to find copies. Printz Award winners: • 2019 The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo • 2018: We Are Okay, by Nina LaCour • 2017: March, by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell. • 2016: Bone Gap, by Laura Ruby. • 2015: I'll Give You the Sun, by Jandy Nelson. • 2014: Midwinterblood, by Marcus Sedgwick. • 2013: In Darkness, by Nick Lake. • 2012: Where Things Come Back, by John Corey Whaley. -

SUGGESTED TEXTS for the English K–10 Syllabus

SUGGESTED TEXTS for the English K–10 Syllabus SUGGESTED TEXTS for the English K–10 Syllabus © 2012 Copyright Board of Studies NSW for and on behalf of the Crown in right of the State of New South Wales. This document contains Material prepared by the Board of Studies NSW for and on behalf of the State of New South Wales. The Material is protected by Crown copyright. All rights reserved. No part of the Material may be reproduced in Australia or in any other country by any process, electronic or otherwise, in any material form or transmitted to any other person or stored electronically in any form without the prior written permission of the Board of Studies NSW, except as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968. School students in NSW and teachers in schools in NSW may copy reasonable portions of the Material for the purposes of bona fide research or study. Teachers in schools in NSW may make multiple copies, where appropriate, of sections of the HSC papers for classroom use under the provisions of the school’s Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) licence. When you access the Material you agree: • to use the Material for information purposes only • to reproduce a single copy for personal bona fide study use only and not to reproduce any major extract or the entire Material without the prior permission of the Board of Studies NSW • to acknowledge that the Material is provided by the Board of Studies NSW • not to make any charge for providing the Material or any part of the Material to another person or in any way make commercial use of the Material without the prior written consent of the Board of Studies NSW and payment of the appropriate copyright fee • to include this copyright notice in any copy made • not to modify the Material or any part of the Material without the express prior written permission of the Board of Studies NSW.