Plainsong Or Polyphony?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lexile Framework® for Reading Matching Students to Text!

8068528 The Lexile Framework® for Reading Matching students to text! Matching students to texts at appropriate levels helps to increase their confidence, competence, and control over the reading process. The Lexile Framework is a reliable and tested tool designed to bridge two critical aspects of student reading achievement — levelling text difficulty and assessing the reading skills of each student. SCHOOL YEAR LEXILE LEVEL BENCHMARK LITERATURE SAMPLE TEXT PASSAGES The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1530 Strange Objects Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray 1270 When the Minister for National Heritage engaged me to translate the manuscript which Strange Objects by Gary Crew 1200 appears for the first time in this paper today, I expected the task would be purely academic. 1200L– War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy 1200 Naturally, I was honoured to be undertaking the translation of such an important work, and eager to provide as accurate an interpretation of the text as I could, but nothing could Great Expectations by Charles Dickens 1200 12 1700L have prepared me for the human element, the personality of the writer. Fired Up by Sarah Ell 1180 The Wind in the Willows Animal Farm by George Orwell 1170 ‘Look here,’ he went on, ‘this is what occurs to me. There’s a sort of dell down there in front The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells 1170 of us, where the ground seems all hilly and humpy and hummocky. We’ll make our way Diary Z by Stephanie McCarthy 1140 down into that, and try and find some sort of shelter, a cave or hole with a dry floor to it, out of the snow and the wind, and there we’ll have a good rest before we try again, for we’re The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame 1140 11 1100L both of us pretty dead beat. -

Middle Years (6-9) 2625 Books

South Australia (https://www.education.sa.gov.au/) Department for Education Middle Years (6-9) 2625 books. Title Author Category Series Description Year Aus Level 10 Rules for Detectives MEEHAN, Adventure Kev and Boris' detective agency is on the 6 to 9 1 Kierin trail of a bushranger's hidden treasure. 100 Great Poems PARKER, Vic Poetry An all encompassing collection of favourite 6 to 9 0 poems from mainly the USA and England, including the Ballad of Reading Gaol, Sea... 1914 MASSON, Historical Australia's The Julian brothers yearn for careers as 6 to 9 1 Sophie Great journalists and the visit of the Austrian War Archduke Franz Ferdinand aÙords them the... 1915 MURPHY, Sally Historical Australia's Stan, a young teacher from rural Western 6 to 9 0 Great Australia at Gallipoli in 1915. His battalion War lands on that shore ready to... 1917 GARDINER, Historical Australia's Flying above the trenches during World 6 to 9 1 Kelly Great War One, Alex mapped what he saw, War gathering information for the troops below him.... 1918 GLEESON, Historical Australia's The story of Villers-Breteeneux is 6 to 9 1 Libby Great described as wwhen the Australians held War out against the Germans in the last years of... 20,000 Leagues Under VERNE, Jules Classics Indiana An expedition to destroy a terrifying sea 6 to 9 0 the Sea Illustrated monster becomes a mission involving a visit Classics to the sunken city of Atlantis... 200 Minutes of Danger HEATH, Jack Adventure Minutes Each book in this series consists of 10 short 6 to 9 1 of Danger stories each taking place in dangerous situations. -

Saving Francesca

TEACHERS ’ RESOURCES RECOMMENDED FOR Upper secondary Ages 14+; years 9 to 12 CONTENTS 1. Plot summary 1 2. About the author 2 3. About the book 2 4. Mode of telling 2 5. Key themes and study topics 3–8 6. Further reading 8–9 KEY CURRICULUM AREAS Learning areas: English General capabilities: Language, Literature, Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability REASONS FOR STUDYING THIS BOOK To analyse how language and writing evoke mood, tone and character To discuss what makes a story and its characters extraordinary and fully realised To discuss identity and self-actualisation To discuss gender difference and what Saving Francesca feminism means today; to contrast this with feminism’s origins and the changing role of girls Melina Marchetta and women To encourage creative and imaginative writing To discuss resilience and mental health PLOT SUMMARY Francesca is at the beginning of her second term in THEMES Year Eleven at an all boy’s school that has just started Identity accepting girls. She misses her old friends, and, to Friendship make things worse, her mother has had a breakdown Family Feminism and can barely move from her bed. Humour But Francesca had not counted on the fierce loyalty of Mental health her new friends, or falling in love, or finding that it’s Memory within her to bring her family back together. PREPARED BY A memorable and much-loved Australian classic Penguin Random House Australia and Judith Ridge filled with humour, compassion and joy, from the internationally bestselling and multi-award-winning PUBLICATION DETAILS author of Looking for Alibrandi. -

Ysd Ar 2010-11

Delaware Library Association Youth Services Division Annual Report to the DLA President, 2010 – 2011 The Children’s Services Division has been active for the year 2010 – 2011, especially with the Delaware Blue Hen Children’s Choice Book Award, which the division sponsors, and the Summer Reading Club in which all public libraries and the Dover Air Force base library participate. The officers for the division for this year have been: Maureen Miller, Lewes Public Library, President Audrey Avery, Dover Public Library, Vice President Sherri Scott, Georgetown Public Library, Secretary-Treasurer Activities of the division include: 1. The Summer Reading Club theme for 2010 was “Make a Splash at Your Library”. The statistics (with 35 libraries reporting) were: Registration = 14,195 (13,147 children, 1048 teens) Completions = 8,038 (7482 children, 556 teens) Percentage of Completions = 56% 2. The 2011 Delaware Blue Hen Children’s Choice Book Awards were voted on by the children of Delaware . The winners were: Picture Book: Tiger Pups by Tom and Allie Harvey Chapter Book: A Season of Gifts by Richard Peck Teen Book: If I Stay by Gayle Forman 3. The 2012 Delaware Blue Hen Children’s Choice Book Award nominees were selected by the youth service award committees. The voting will take place from March 1 to September 31, 2011. The ballots are attached. The winners will be announced on the first Saturday in November 7, 2011, in each public library in the state, along with the official press release. The nominees are as follows: Early Readers: Chalk by -

Talking Books for Children – Ausgewählte Untersuchungen Zum Hörbuchangebot Für Kinder in Australien

Talking books for children – Ausgewählte Untersuchungen zum Hörbuchangebot für Kinder in Australien Diplomarbeit im Fach Kinder- und Jugendmedien Studiengang Öffentliche Bibliotheken der Fachhochschule Stuttgart – Hochschule der Medien Daniela Kies Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr. Horst Heidtmann Zweitprüfer: Prof. Dr. Manfred Nagl Bearbeitungszeitraum: 15. Juli 2002 bis 15. Oktober 2002 Stuttgart, Oktober 2002 Kurzfassung 2 Kurzfassung Gegenstand der hier vorgestellten Arbeit ist das Hörbuchangebot für Kinder in Austra- lien. Seit Jahren haben Gesellschaften für Blinde Tonträger für die eigenen Bibliothe- ken produziert, um blinden oder sehbehinderten Menschen zu helfen. Hörmedien von kommerziellen Produzenten, in Australien ist ABC Enterprises der größte, sind in der Regel gekürzte Versionen von Büchern. Bolinda Audio arbeitet kommerziell, veröffent- licht aber nur ungekürzte Versionen. Louis Braille Audio und VoyalEyes sind Abteilun- gen von Organisationen für Blinde, die Tonträger auch an Bibliotheken verkaufen und sie sind auch im Handel erhältlich. Grundsätzlich gelten öffentliche Bibliotheken als Hauptzielgruppe und ihnen werden spezielle Dienstleistungen von den Verlagen selbst oder dem Bibliothekszulieferer angeboten. Die britische und amerikanische Konkurrenz ist im Kindertonträgerbereich besonders groß. Aus diesem Grund spezialisieren sich australische Hörbuchverlage auf die Produktion von Büchern australischer Autoren und/ oder über Australien. Bei Kindern sind die Autoren John Marsden, Paul Jennings und Andy Griffiths sehr beliebt. Stig Wemyss, ein ausgebildeter Schauspieler, hat zahl- reiche Bücher bei verschiedenen Verlagen erfolgreich gelesen. Musik bzw. Lieder wer- den auf Hörbüchern nur vereinzelt verwendet. Es gibt aber einige Gruppen, z.B. die Wiggles, und Entertainer, z.B. Don Spencer, die Lieder für Kinder schreiben und auf- nehmen. Da der Markt für Kindertonträger in Australien noch im Aufbau ist, lohnt es sich, die Entwicklungen weiter zu verfolgen. -

Disenchantment: a Novel for Young Adults with a Discussion of Representations of Indigenous Australians and Native Americans in Books for Children and Young Adults

Disenchantment: a novel for young adults With a discussion of representations of Indigenous Australians and Native Americans in books for children and young adults Rebecca Louise Hazleden BA (hons), (Leeds) MA, (Leeds Metropolitan University) PhD, (Exon) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of English, Media Studies and Art History 1 Abstract This thesis is in two parts. The first is the creative project, a love story called Disenchantment, which is a speculative fiction novel for young adults. The novel consists of the testimony of an imprisoned girl, indigenous to a fictitious island, explaining how she has ended up in a prison cell condemned to hang for a murder she did not commit. As she relates her story to a visitor, a tale emerges of love and betrayal set against a backdrop of colonialism and violence. At first, Neka is an awkward and fearful little child, suckled by a half-dead mother and weaned by a bitter old Healer. The adults remark what a pity it is that the bright light of her mother was snuffed out by such a dull child. But then she is chosen as assistant to Elu, the beautiful and vibrant rebel girl from another clan, who is to be the new Healer. They embark on their training together, drawing closer, learning the secrets of the clan, healing the sick, talking to the dead, encountering the god of lightning, and awakening the god of spring. Neka starts to find her place in the world, and her love blossoms – love for her land, her people, and most of all for Elu. -

7-9 Booklist by Title - Full

7-9 Booklist by Title - Full When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. This title also appears on the 9plus booklist. This title is usually read by students in years 9, 10 and above. PRC Title/Author Publisher Year ISBN Annotations 5638 1000-year-old boy, The HarperCollins 2018 9780008256944 Alfie Monk is like any other pre-teen, except he's 1000 years old and Welford, Ross Children's Books can remember when Vikings invaded his village and he and his family had to run for their lives. When he loses everything he loves in a tragic fire and the modern world finally catches up with him, Alfie embarks on a mission to change everything by finally trusting Aidan and Roxy enough to share his story, and enlisting their help to find a way to, eventually, make sure he will eventually die. 22034 13 days of midnight Orchard Books 2015 9781408337462 Luke Manchett is 16 years old with a place on the rugby team and the Hunt, Leo prettiest girl in Year 11 in his sights. Then his estranged father suddenly dies and he finds out that he is to inherit six million dollars! But if he wants the cash, he must accept the Host. A collection of malignant ghosts who his Necromancer father had trapped and enslaved! Now the Host is angry, the Host is strong, and the Host is out for revenge! Has Luke got what it takes to fight these horrifying spirits and save himself and his world? 570824 13th reality, The: Blade of shattered hope Scholastic Australia 2018 9781742998381 Tick and his friends are still trying to work out how to defeat Mistress Dashner, James Jane, but when there are 13 realities from which to draw trouble, the battle is 13 times as hard. -

Printz Award Winners

The White Darkness The First Part Last Teen by Geraldine McCaughrean by Angela Johnson YF McCaughrean YF Johnson 2008. When her uncle takes her on a 2004. Bobby's carefree teenage life dream trip to the Antarctic changes forever when he becomes a wilderness, Sym's obsession with father and must care for his adored Printz Award Captain Oates and the doomed baby daughter. expedition becomes a reality as she is soon in a fight for her life in some of the harshest terrain on the planet. Postcards From No Man's Winners Land American Born Chinese by Aidan Chambers by Gene Luen Yang YF Chambers YGN Yang 2003. Jacob Todd travels to 2007. This graphic novel alternates Amsterdam to honor his grandfather, between three interrelated stories a soldier who died in a nearby town about the problems of young in World War II, while in 1944, a girl Chinese Americans trying to named Geertrui meets an English participate in American popular soldier named Jacob Todd, who culture. must hide with her family. Looking for Alaska A Step From Heaven by John Green by Na An YF Green YF An 2006. 16-year-old Miles' first year at 2002. At age four, Young Ju moves Culver Creek Preparatory School in with her parents from Korea to Alabama includes good friends and Southern California. She has always great pranks, but is defined by the imagined America would be like search for answers about life and heaven: easy, blissful and full of death after a fatal car crash. riches. But when her family arrives, The Michael L. -

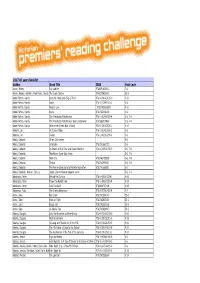

FINAL 2017 All Years Booklist.Xlsx

2017 All years Booklist Author Book Title ISBN Year Level Aaron, Moses Lily and Me 9780091830311 7-8 Aaron, Moses (reteller); Mackintosh, David (ill.)The Duck Catcher 9780733412882 EC-2 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Does My Head Look Big in This? 978-0-330-42185-0 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Jodie 978-1-74299-010-1 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Noah's Law : 9781742624280 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Rania 9781742990188 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker 978-1-86291-920-4 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker Goes Undercover 9781862919488 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Where the Streets Had a Name 978-0-330-42526-1 9-10 Abdulla, Ian As I Grew Older 978-1-86291-183-3 5-6 Abdulla, Ian Tucker 978-1-86291-206-9 5-6 Abela, Deborah Ghost Club series 5-6 Abela, Deborah Grimsdon 9781741663723 5-6 Abela, Deborah In Search of the Time and Space Machine 978-1-74051-765-2 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Max Remy Super Spy series 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah New City 9781742758558 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Teresa 9781742990941 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Remarkable Secret of Aurelie Bonhoffen 9781741660951 5-6 Abela, Deborah; Warren, Johnny Jasper Zammit Soccer Legend series 5-6, 7-8 Abrahams, Peter Behind the Curtain 978-1-4063-0029-1 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Down the Rabbit Hole 978-1-4063-0028-4 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Into The Dark 9780060737108 9-10 Abramson, Ruth The Cresta Adventure 978-0-87306-493-4 3-4 Acton, Sara Ben Duck 9781741699142 EC-2 Acton, Sara Hold on Tight 9781742833491 EC-2 Acton, Sara Poppy Cat 9781743620168 EC-2 Acton, Sara As Big As You 9781743629697 -

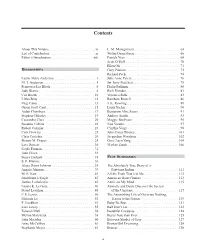

Table of Contents

Contents About This Volume . ix L . M . Montgomery . 64 List of Contributors . xi Walter Dean Myers . 66 Editor’s Introduction . xiii Patrick Ness . 68 Scott O’Dell . 70 Ellen Oh . 71 Biographies Gary Paulsen . 73 Richard Peck . 74 Laurie Halse Anderson . 3 Julie Anne Peters . 76 M . T . Anderson . 4 Sir Terry Pratchett . 78 Francesca Lia Block . 6 Philip Pullman . 80 Judy Blume . 8 Rick Riordan . 81 Coe Booth . 10 Veronica Roth . 83 Libba Bray . 12 Rainbow Rowell . 86 Meg Cabot . 13 J . K . Rowling . 88 Orson Scott Card . 15 Louis Sachar . 90 Aidan Chambers . 17 Benjamin Alire Saenz . 91 Stephen Chbosky . 19 Andrew Smith . 93 Cassandra Clare . 20 Maggie Stiefvater . 95 Suzanne Collins . 22 Ned Vizzini . 97 Robert Cormier . 23 Cynthia Voigt . 98 Cath Crowley . 25 John Corey Whaley . 101 Chris Crutcher . 26 Jacqueline Woodson . 102 Sharon M . Draper . 28 Gene Luen Yang . 104 Lois Duncan . 30 Markus Zusak . 106 Gayle Forman . 31 John Green . 33 Sonya Hartnett . 35 Plot Summaries S . E . Hinton . 36 Alaya Dawn Johnson . 38 The Absolutely True Diary of a Angela Johnson . 39 Part-time Indian . 111 M . E . Kerr . 41 All the Truth That’s in Me . 112 Madeleine L’Engle . 43 American Born Chinese . 113 Justine Larbalestier . 45 Annie on My Mind . 115 Ursula K . Le Guin . 46 Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets David Levithan . 48 of the Universe . 117 C .S . Lewis . 50 The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Malinda Lo . 51 Traitor to the Nation . 119 E . Lockhart . 53 Baby Be-Bop . 121 Lois Lowry . 55 Ball Don’t Lie . -

Walter Mcvitty Books Publisher's Archive

A Guide to the Walter McVitty Books Publisher’s Archive The Lu Rees Archives The Library University of Canberra October 2002 Scope and Content Note • Papers • 1984 – 1997 • 25 boxes • Series 6 (Publishers) is restricted for 15 years. (2003-2018) • Series 9, (Finance and Sales) is restricted for 15 years. (2003-2018) These papers were donated to the Lu Rees Archives in 2000 under the Cultural Gifts Program. The papers are a complete record of the publishing company ‘Walter McVitty Books’, from its inception in 1985 until it’s sale in 1997. They are unique because this company was the only publisher to exclusively publish Australian children’s books. The papers include correspondence, reviews, artwork, contracts, awards, financial statements, manuscripts, book dummies and publicity materials. The major correspondents are the authors and illustrators, especially Colin Thiele and John Marsden; other publishers, and book clubs and associations. This finding aid was prepared by Management of Archives students Kerri Kemister, Wendy-Anne Quarmby and Lisa Roulstone, under the supervision of Professor Belle Alderman. Walter McVitty Biographical Note Prepared by: Cathie Bartley, Karen Ottoway and Amanda Rebbeck. Teacher, teacher librarian, tertiary lecturer, critic, editor, author and publisher Walter McVitty was born in Melbourne in 1934 and has been involved in the field of children’s literature for over four decades. He taught in schools in Victoria and worked overseas for five years before undertaking a librarianship course at Melbourne Teachers College in 1962. He was a teacher librarian in Victoria for six years, then Senior Lecturer in children's literature at Melbourne Teachers College for fifteen years before establishing his own small publishing company, Walter McVitty Books, with his wife Lois in 1985. -

The Children's Book Council of Australia Book of the Year Awards

THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — CONTENTS Page BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — 1981 . 2 BOOK OF THE YEAR: OLDER READERS . .. 7 BOOK OF THE YEAR: YOUNGER READERS . 12 VISUAL ARTS BOARD AWARDS 1974 – 1976 . 17 BEST ILLUSTRATED BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 17 BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD: EARLY CHILDHOOD . 17 PICTURE BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 20 THE EVE POWNALL AWARD FOR INFORMATION BOOKS . 28 THE CRICHTON AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 32 CBCA AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 33 CBCA BOOK WEEK SLOGANS . 34 This publication © Copyright The Children’s Book Council of Australia 2021. www.cbca.org.au Reproduction of information contained in this publication is permitted for education purposes. Edited and typeset by Margaret Hamilton AM. CBCA Book of the Year Awards 1946 - 1 THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 – From 1946 to 1958 the Book of the Year Awards were judged and presented by the Children’s Book Council of New South Wales. In 1959 when the Children’s Book Councils in the various States drew up the Constitution for the CBC of Australia, the judging of this Annual Award became a Federal matter. From 1960 both the Book of the Year and the Picture Book of the Year were judged by the same panel. BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD 1946 - 1981 Note: Until 1982 there was no division between Older and Younger Readers. 1946 – WINNER REES, Leslie Karrawingi the Emu John Sands Illus. Walter Cunningham COMMENDED No Award 1947 No Award, but judges nominated certain books as ‘the best in their respective sections’ For Very Young Children: MASON, Olive Quippy Illus.