Appendix: Tables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Hadejia Emirate, Nigeria (1906-1960)

COLONIALISM AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES: A CASE STUDY OF HADEJIA EMIRATE, NIGERIA (1906-1960) BY MOHAMMED ABDULLAHI MOHAMMED MAH/42421/141/DF A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE COLLEGE OF HIGHER DEGREES AND RESEARCH IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY OF KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY MAY, 2015 DECLARATION This is my original work and has not been presented for a Degree or any other academic award in any university or institution of learning. ~ Signature Date MOHAMMED ABDULLAHI MOHAMMED APPROVAL I confirm that the work in this dissertation proposal was done by the candidate under my supervision. Signiture Supervisor name Date Peter Ssekiswa DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my late mother may her soul rest in perfect peace and my humble brother Yusif Bashir Hekimi and my wife Rahana Mustathha and the entire fimily In ACKNOWLEDGEMENT lam indeed grateful to my supervisor Peter Ssekiswa , who tirelessly went through my work and inspired me to dig deeper in to the core of the m matter , His kind critism patience and understanding assrted me a great deal Special thanks go to Vice Chancellor prof P Kazinga also a historian for his courage and commitment , however special thanks goes to Dr Kayindu Vicent , the powerful head of department of education (COEDU ) for friendly and academic discourse at different time , the penalist of the viva accorded thanks for observation and scholarly advise , such as Dr SOFU , Dr Tamale , Dr Ijoma My friends Mustafa Ibrahim Garga -

1F35e3e1-Thisday-Jul

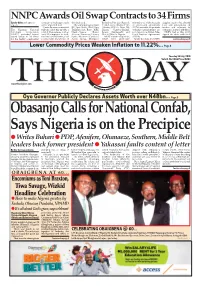

NNPC Awards Oil Swap Contracts to 34 Firms Ejiofor Alike with agency contracts to exchange crude the deals said. Barbedos/Petrogas/Rainoil; referred to as offshore crude supplies crude oil to selected reports oil for imported fuel. The winning groups include: UTM/Levene/Matrix/Petra oil processing agreements local and international oil Under the new contract that BP/Aym Shafa; Vitol/Varo; Atlantic; TOTSA; Duke Oil; (OPAs) and crude-for-products traders and refineries in The Nigerian National will take effect this month, a Trafigura/AA Rano; MRS; Sahara; Gunvor/Maikifi; exchange arrangements, are exchange for petrol and diesel. Petroleum Corporation total of 15 groupings, with at Oando/Cepsa; Bono/ Litasco /Brittania-U; and now known as Direct Sale- NNPC had in May 2017, (NNPC) yesterday issued least 34 companies in total, Akleen/Amazon/Eterna; Mocoh/Mocoh Nigeria. Direct Purchase Agreements signed the deals with local award letters to oil firms received award letters, four Eyrie/Masters/Cassiva/ NNPC’s crude swap deals, (DSDP). for the highly sought-after sources with knowledge of Asean Group; Mercuria/ which were previously Under the deals, the NNPC Continued on page 8 Lower Commodity Prices Weaken Inflation to 11.22%... Page 8 Tuesday 16 July, 2019 Vol 24. No 8863 Price: N250 www.thisdaylive.com T RU N TH & REASO Oyo Governor Publicly Declares Assets Worth over N48bn... Page 9 Obasanjo Calls for National Confab, Says Nigeria is on the Precipice Writes Buhari PDP, Afenifere, Ohanaeze, Southern, Middle Belt leaders back former president Yakassai faults content of letter By Our Correspondents plunging into an abyss of before Nigeria witnesses the varied reactions from some aligned with Obasanjo’s Forum (ACF), Alhaji Tanko insecurity. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

The Role of Traditional Rulers in Conflict Prevention and Mediation in Nigeria

The Role of Traditional Rulers in Conflict Prevention and Mediation in Nigeria Interim Report Roger Blench Selbut Longtau Umar Hassan Martin Walsh Prepared for DFID, Nigeria Saturday, 29 April 2006 The Role of Traditional Rulers in Conflict Prevention and Mediation in Nigeria: Interim Report TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................................ii 1. Introduction: background to the study ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Literature review ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Other countries in West Africa................................................................................................................ 4 1.4 Historical development of Emirate/traditional councils.......................................................................... 4 1.5 The nature of the ruler in Islamic conceptions........................................................................................ 6 1.6 Methods................................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Traditional leadership institutions in -

Resolutions of the House from 6Th June 2012- June 2014

Resolutions of the House from 6th June 2012- June 2014 S/N Title of Motion Sponsor (s) Date of Resolutions Committee Referred Debate/ Referral 1. The Frequent and Recent night Hon. Sani 19/6/12 1. Condemn the barbaric killing of innocent people as well as raids and killings of innocent Ibrahim the destruction of their property. inhabitants of Dangulbi town 2. Condone with the people and Government of Zamfara State and its neighbouring villages and the entire bereaved families. in Dansadau Emirate of Maru 3. Urge the Inspector-General of Police and other relevant Local Government Area in security agencies to step up action and fish out the Zamfara State perpetrators of the heinous Act, with a view to bringing them to justice. 4. Further urge the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) to provide relief materials to the members of the affected communities as a matter of urgency. 2 Attacks on Places of Worship Hon. Yakubu 19/6/2012 1. Condemn without hesitation the acts of violence in Kaduna, in Kaduna State Umaru Bade Yobe and other parts of the country. 2. Commiserate with the people who lost their loved ones and properties; 3. Commend the Governor of Kaduna State for his prompt response to the situation; 4. Urge the National Emergency management Agency (NEMA) to assist victims with relief materials. 5. Mandate the relevant Security Committees to meet with the Hon. Minister of Defence, National Security Adviser, Inspector General of Police and other Security Agencies for a way forward and report back to the House within two (2) weeks. -

Women in Politics in Nigeria

Sixth Global Forum on Gender Statistics Statistics Finland and United Nations Statistics Division Helsinki, Finland, 24 to 26 October 2016 Venue: Säätytalo House of the Estates, Snellmaninkatu 9-11 MONITORING PARTICIPATION OF WOMEN IN POLITICS IN NIGERIA BY OLUYEMI OLOYEDE HEAD OF GENDER STATISTICS DEMOGRAPHIC AND SOCIAL STATISTICS DEPARTMENT NATIONAL BUREAU OF STATISTICS, 762, INDEPENDENCE AVENUE, CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT, ABUJA, NIGERIA Table of Content • Introduction • Objective • Women in Pre-Colonial Era • Women in Colonial Period • Women in Post-Colonial Period • Women in the second Republic (1979 – 1983) • Return of Military Rule (December 1983) • Third Republic • Re-introduction of Democracy (The Fourth Republic) • Effort made towards female participation in Politics in Nigeria • Challenges Affecting Women Participation in Politics in Nigeria • Recommendation • Conclusion • End of Presentation Introduction • Nigeria has been recording low participation of women in both elective and appointive positions. • Efforts have been made by government and non- governmental organizations to increase the level of participation in line with the declaration made at the fourth World Conference on women in Beijing, which advocated 30% affirmative action. • National Gender Policy (NGP) recommended 35% affirmative action Objectives They are: • To review the importance of data in monitoring women participation in politics in Nigeria vis-à-vis the affirmative declaration. • To examine factors militating against women participation in politics. Women in Pre-Colonial Era • In the era, Nigerian women were an integral part of the political set up of their communities • See the table in the next slide Table 1: Statistics of Women Traditional Rulers in Pre-colonial days. S/N Name Town/Village LGA State Type of Rule Date 1 Luwo Ife Ife Central L.G. -

Page 1 of 27 Nigeria and the Politics of Unreason 7/21/2008

Nigeria and the Politics of Unreason Page 1 of 27 Nigeria and the Politics of Unreason: Political Assassinations, Decampments, Moneybags, and Public Protests By Victor E. Dike Introduction The problems facing Nigeria emanate from many fronts, which include irrational behavior (actions) of the political elite, politics of division, and politics devoid of political ideology. Others factors are corruption and poverty, lack of distributive justice, regional, and religious cleavages. All these combine to create crises (riots and conflicts) in the polity, culminating in public desperation and insecurity, politics of assassinations, decampments (carpet crossing), moneybags, and public protests. All this reached its climax during the 2003 elections. When the nation thinks it is shifting away from these forces, they would somersault and clash again creating another political thunderstorm. It looks that the society would hardly outgrow ‘the politics of unreason’ (Lipset and Raab, 1970), which is often politics of extremism, because the political class is always going beyond the limits of what are reasonable to secure or retain political power. During the 2003 elections moneybags (instead of political ideology) directed political actions in political parties; and it also influenced the activities of many politicians. As a result, the presidential candidates of the two major political parties (PDP and ANPP) cliched their party tickets by stuffing the car boots, so to say, of their party delegates with Ghana-Must- Go bags. This frustrated and intimidated their political opponents within (and those in the other minor political parties). Since after his defeat by Chief Olusegun Obasanjo in the 2003 PDP primary in Abuja, Dr. -

(George Mason University), Questions About How Partition. Inaddition

ISLAM AND DEMOCRATIC FEDERALISM IN NIGERIA By John Paden (George Mason University), The Nigerian return to democratic federalism in 1999, after 15 years of centralized military rule, has raised questions about how to decentralize without provoking sentiments for partition. Inaddition, the 1999 presidential election witnessed a voluntary "power shift" from the northern region to the southwest, and in both major parties-the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) and the Alliance for Democracy/All Peoples Party (AD/APP)-the presidential candidates were from the "Christian" southwest and the vice presidential candidates from the "Muslim" north. This paper examines how regional and ethno-religions factors have emerged since the transition to civilian rule in 1999,. The most obvious issues are the revival of Shari'a law in the criminal domain in the far northern states, the subsequent patterns of ethno-religious conflict (especially in the large northern urban centres), the impact of the events of September 11 on elite and grassroots populations, and the challenge of insulating democratic processes from religious polarization. The global context too has changed. In October 2001 at the Muslim foreign ministers meeting in Qatar, the 56 members of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) agreed to condemn terrorism and ignore the Taliban's call for jihad against Christians and Jews. Yet, OIC national leaders also must deal with public opinion in their own countries, and the question of external influences is never far from the surface. As a large and complex "religiously mixed" country in the midst of a political transition, I Nigeria is a special challenge. -

Yusuf Muhammad ADAMU Sex: Male Nationality: Nigerian Date of Birth

CURRICULUM VITAE PERSONAL PROFILE Full name: Yusuf Muhammad ADAMU Sex: Male Nationality: Nigerian Date of birth: 9th March 1968 Place of birth Katsina State of Origin Zamfara Local Government Tsafe Permanent home address: 41, Ibrahim Tela Street, Giginyu Qtrs. Kano Contact address: Department of Geography, Bayero University, Kano. E-mail: [email protected] /[email protected] Telephone: 08034064325/07081929171 Marital status: Married with children INSTITUTIONS ATTENDED AND CERTIFICATES OBTAINED WITH DATES School Years Certificate Date Giginyu Primary School, Kano 1974-1980 Primary Certificate 1980 Government Secondary School Koko 1980-1982 N.A N.A Govt. Science Sec. School Zuru 1982-1985 General School Certificate 1985 Usmanu Danfodio University Sokoto 1985-1990 B.Sc (Hons) Geography 1990 University of Ibadan 1992-1994 M.Sc Geography 1994 Bayero University, Kano 1997-2003 PhD Geography 2004 1 NYSC (GSSS Dutsin Ma Katsina State) 1991-1992 Discharge Certificate 1992 HONOURS AND DISTINCTIONS i) Usmanu Danfodiyo University Merit Award 1987 ii) Kaduna State Council of Arts and Culture Literary Award 1990 iii) Katsina State NYSC Commendation Award 1992 iv) School of African and Asian Studies, Univ. of Sussex Honorary Visiting Fellowship 1998 v) Social Science Academy of Nigeria Thesis Grant 1998 vi) Fulbright Fellowship ( School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham) 2001 vii) Association of Nigerian Authors Kano State Chapter Merit Award 2003 viii) Hausa Authors Forum Merit Award 2006 ix) Giginyu PTA Contribution to Education Award 2009 x) 1Special recognition by the Association of American Geographers 2013 xi) Certificate of Honour by Giginyu Special Primary School 2017 xii) 2Certificate of Appreciation by Giginyu Forum 2017 xiii) 3Karramawa daga Ýan Ajin HAU 301 2017 PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIP Member, Association of Nigerian Geographers 1996-date Member, Association of Nigerian Authors 1995-date Member, Nigerian Academy of Letters Aug. -

The Geography of Frontiers and Boundaries

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 02:01 24 May 2016 ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY Volume 13 THE GEOGRAPHY OF FRONTIERS AND BOUNDARIES Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 02:01 24 May 2016 This page intentionally left blank Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 02:01 24 May 2016 THE GEOGRAPHY OF FRONTIERS AND BOUNDARIES J. R. V. PRESCOTT Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 02:01 24 May 2016 First published in 1965 This edition first published in 2015 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 1965 J. R. V. Prescott All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-1-138-80830-0 (Set) eISBN: 978-1-315-74725-5 (Set) ISBN: 978-1-138-81362-5 (Volume 13) eISBN: 978-1-315-74796-5 (Volume 13) Publisher’s Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. -

Bayajidda the Prince of Bagdad in Hausa Land

afrika focus — Volume 32, Nr. 1, 2019 — pp. 125-136 MEMORIALIZING A LEGENDARY FIGURE: BAYAJIDDA THE PRINCE OF BAGDAD IN HAUSA LAND Abubakar Aliyu Liman Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria This paper examines the various ways in which the Bayajidda legend is memorialized. In its current manifestations, the legend can be seen as an important agency for the remembrance of the past in the context of rapid socio-historical change in Africa, under the influence of modernity, technology and glo- balization. The analysis begins by highlighting the interface between folklore and history in everyday cultural practices in postcolonial northern Nigeria. The signposts that give a coherent structure to the paper include the chronicles of the Bayajidda legend, the essential oral version circulating in its different forms in Hausa society. Over the years, reference to the legend of Bayajidda has always been made through the use of different modes of cultural expression such as song, dramatic performance, film and other forms of narration. This range has served the political and ideological interests of the dominant power elite who are consistently alluding to the Bayajidda legend. The survival of the essential oral narrative therefore depends solely on a strategy of alluding to the legend in its various guises, including the form of museum artifacts, drama, films and musical songs. However, the paper explores each of the specific historical periods from the pre-colonial down to the colonial and postcolonial epochs with a view to highlighting how specific forms of the legend are deployed by hegemonic structures for the purposes of legitimation. KEYWORDS: BAYAJIDDA, LEGEND, HISTORY, HAUSA KINGDOM, MEMORIALIZATION, RECREATION Introduction The analysis below is divided into three broad categories. -

Annual Report of the Colonies, Nigeria, 1934

PRINTS IN. NIGERIA , . * PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY 0F7ICE To be wife!uned Erectly from H.M. STATIONERY omCE at the Mowing *44r**e* I Altst*! Home, K>way, London, W.Ca j tzo George Street, Edtntorgli * | YorkStiwlfc Umc)mm if t St. *******Cre«*rt*Ctnfift* So CUdMttet S*r«t, OeJfwt$ of tfrwgb *ay Boofedfcr 1435 ' ' ' fl - ' f '. .... V - >'V' M • etc., of Imperial and Interest 1 AH CCOIQ&C SUBVIY •A 2*. 6rf, (2#. 9i.) Part II—Eastern, Mediterranean, and Pudfiq. 3*. W. (8*. 9d.) Part in—Wert Indie*. 3*. 6d, (3*. 9&) COLONIAL REGULATIONS. , - Begotatione loir Hit Jtfajeftty'e Ck>JoafaI Service. Parti—Public Officer. , . LOaloal*!^ [Ooloriial No. m **- (to- to Ut S&tfon, lit Jami* 1834. 193*.; ;\ - - :*'V * ^< - ..7 BMPIRR SOU?Hr. Oonfoxerjoe of Empire Surray Officer*, 1931 [gonial N* tOJ #1 1 IMPERIAL ECONOMIC CONFERENCE, OTTAWA, 1933, Summary of Proceeding* and coruee or IVade Agreement*. Appendioee to the Sonuaery ol Proceedings 417*1.] fr.-(3t.*t4.). Import of foyirtCtauniai^ ; CLOSER UHIONIN EAST jurats ^I^^J^ §gWa«WS °^8er * *>» D9»~—te e in Batterv*r Vol, HI—Amwridice* ... ... ..4 4*. 6d\ (*>. a*). KBHYA LAHD OOltMI&SIOK, • Ro^^twWa^S. ^ [Cmd, 4666,] lie, (11* Uh Evider** w$ Memamnda, [Colonial No. 91.] • Vol. T . ... ... vara ... ... ... w%..'yfWPL . Summary oi Oonolueione mohed by Hie Mejeety>e ^^^j ^ ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE IN BAST AFRICA. , ,V V ' 1 iWrtTftbe Commieeioo of inquiry into the admkfctotion of Ju,W in genya, Uganda, and the Tanganyika Territory ^nm^l ^tt^; . gvi&noe andHetn<^d». (Colonial No. 96.] faffrfyW AU prices ore *eL .^*<N« w> postage.