UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![A Sociolinguistic Profile of the Kyoli (Cori) [Cry] Language of Kaduna State, Nigeria](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1146/a-sociolinguistic-profile-of-the-kyoli-cori-cry-language-of-kaduna-state-nigeria-51146.webp)

A Sociolinguistic Profile of the Kyoli (Cori) [Cry] Language of Kaduna State, Nigeria

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2020-012 A Sociolinguistic Profile of the Kyoli (Cori) [cry] Language of Kaduna State, Nigeria Ken Decker, John Muniru, Julius Dabet, Benard Abraham, Jonah Innocent A Sociolinguistic Profile of the Kyoli (Cori) [cry] Language of Kaduna State, Nigeria Ken Decker, John Muniru, Julius Dabet, Benard Abraham, Jonah Innocent SIL International® 2020 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2020-012, October 2020 © 2020 SIL International® All rights reserved Data and materials collected by researchers in an era before documentation of permission was standardized may be included in this publication. SIL makes diligent efforts to identify and acknowledge sources and to obtain appropriate permissions wherever possible, acting in good faith and on the best information available at the time of publication. Abstract This report describes a sociolinguistic survey conducted among the Kyoli-speaking communities in Jaba Local Government Area (LGA), Kaduna State, in central Nigeria. The Ethnologue (Eberhard et al. 2020a) classifies Kyoli [cry] as a Niger-Congo, Atlantic Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Plateau, Western, Northwestern, Hyamic language. During the survey, it was learned that the speakers of the language prefer to spell the name of their language <Kyoli>, which is pronounced as [kjoli] or [çjoli]. They refer to speakers of the language as Kwoli. We estimate that there may be about 7,000 to 8,000 speakers of Kyoli, which is most if not all the ethnic group. The goals of this research included gaining a better understanding of the role of Kyoli and other languages in the lives of the Kwoli people. Our data indicate that Kyoli is used at a sustainable level of orality, EGIDS 6a. -

Nigeria: a New History of a Turbulent Century

More praise for Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century ‘This book is a major achievement and I defy anyone who reads it not to learn from it and gain greater understanding of the nature and development of a major African nation.’ Lalage Bown, professor emeritus, Glasgow University ‘Richard Bourne’s meticulously researched book is a major addition to Nigerian history.’ Guy Arnold, author of Africa: A Modern History ‘This is a charming read that will educate the general reader, while allowing specialists additional insights to build upon. It deserves an audience far beyond the confines of Nigerian studies.’ Toyin Falola, African Studies Association and the University of Texas at Austin About the author Richard Bourne is senior research fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London and a trustee of the Ramphal Institute, London. He is a former journalist, active in Common wealth affairs since 1982 when he became deputy director of the Commonwealth Institute, Kensington, and was the first director of the non-governmental Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. He has written and edited eleven books and numerous reports. As a journalist he was education correspondent of The Guardian, assistant editor of New Society, and deputy editor of the London Evening Standard. Also by Richard Bourne and available from Zed Books: Catastrophe: What Went Wrong in Zimbabwe? Lula of Brazil Nigeria A New History of a Turbulent Century Richard Bourne Zed Books LONDON Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century was first published in 2015 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK www.zedbooks.co.uk Copyright © Richard Bourne 2015 The right of Richard Bourne to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 Typeset by seagulls.net Index: Terry Barringer Cover design: www.burgessandbeech.co.uk All rights reserved. -

Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI Project, Nigeria

l- World Health Organization African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control FINAL RËPOftî ,i ={ Evaluation of the Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI Project, Nigeria N ove m ber- Decem ber 2004 Elizabeth Elhassan (Team Leader) Uwem Ekpo Paul Kolo William Kisoka Abraraw Tefaye Hilary Adie f'Ï 'rt\ t- I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS I Table of contents............. ..........2 Abbreviations/Acronyms ................ ........ 3 Acknowledgements .................4 Executive Summary .................5 *? 1. lntroduction ...........8 2. Methodology .........9 2.1 Sampling ......9 2.2 Levels and lnstruments ..............10 2.3 Protocol ......10 2.4 Team Composition ........... ..........11 2.5 Advocacy Visits and 'Feedback/Planning' Meetings........ ..........12 2.6 Limitations ..................12 3. Major Findings And Recommendations ........ .................. 13 3.1 State Level .....13 3.2 Local Government Area Level ........21 3.3 Front Line Health Facility Level ......27 3.4 Community Level .............. .............32 4. Conclusions ..........36 4.1 Grading the Overall Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI project.................36 4.2 Grading the Project as a whole .......39 ANNEXES .................40 lnterviews ..............40 Schedule for the Evaluation and Advocacy.......... .................42 Feedback and Planning Meetings, Agenda.............. .............44 Report of the Feedbacl</Planning Meetings ..........48 Strengths And Weaknesses Of The Niger State Cdti Project .. .. ..... 52 Participants Attendance List .......57 Abbrevi -

A Re-Assessment of Government and Political Institutions of Old Oyo Empire

QUAESTUS MULTIDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH JOURNAL A RE-ASSESSMENT OF GOVERNMENT AND POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS OF OLD OYO EMPIRE Oluwaseun Samuel OSADOLA, Oluwafunke Adeola ADELEYE Abstract: Oyo Empire was the most politically organized entity founded by the Yoruba speaking people in present-day Nigeria. The empire was well organized, influential and powerful. At a time it controlled the politics and commerce of the area known today as Southwestern Nigeria. It, however, serves as a paradigm for other sub-ethnic groups of Yoruba derivation which were directly or indirectly influenced by the Empire before the coming of the white man. To however understand the basis for the political structure of the current Yorubaland, there is the need to examine the foundational structure from which they all took after the old Oyo Empire. This paper examines the various political structures that made up government and governance in the Yoruba nation under the political control of the old Oyo Empire before the coming of the Europeans and the establishment of colonial administration in the 1900s. It derives its data from both primary and secondary sources with a detailed contextual analysis. Keywords: Old Oyo Empire INTRODUCTION Pre-colonial systems in Nigeria witnessed a lot of alterations at the advent of the British colonial masters. Several traditional rulers tried to protect and preserve the political organisation of their kingdoms or empires but later gave up after much pressure and the threat from the colonial masters. Colonialism had a significant impact on every pre- colonial system in Nigeria, even until today.1 The entire Yoruba country has never been thoroughly organized into one complete government in a modern sense. -

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

LGA Agale Agwara Bida Borgu Bosso Chanchaga Edati Gbako Gurara

LGA Agale Agwara Bida Borgu Bosso Chanchaga Edati Gbako Gurara Katcha Kontagora Lapai Lavun Magama Mariga Mashegu Mokwa Munya Paikoro Rafi Rijau Shiroro Suleja Tafa Wushishi PVC PICKUP ADDRESS Santali Road, After Lga Secretariat, Agaie Opposite Police Station, Along Agwara-Borgu Road, Agwara Lga Umaru Magajib Ward, Yahayas, Dangana Way, Bida Lga Borgu Lga New Bussa, Niger Along Leg Road, Opp. Baband Abo Primary/Junior Secondary Schoo, Near Divisional Police Station, Maikunkele, Bosso Lga Along Niger State Houseso Assembly Quarters, Western Byepass, Minna Opposite Local Govt. Secretariat Road Edati Lga, Edati Along Bida-Zungeru Road, Gbako Lga, Lemu Gwadene Primary School, Gawu Babangida Gangiarea, Along Loga Secretariat, Katcha Katcha Lga Near Hamdala Motors, Along Kontagora-Yauri Road, Kontagoa Along Minna Road, Beside Pension Office, Lapai Opposite Plice Station, Along Bida-Mokwa Road, Lavun Off Lga Secretariat Road, Magama Lga, Nasko Unguwan Sarki, Opposite Central Mosque Bangi Adogu, Near Adogu Primary School, Mashegu Off Agric Road, Mokwa Lga Munya Lga, Sabon Bari Sarkin Pawa Along Old Abuja Road, Adjacent Uk Bello Primary School, Paikoro Behind Police Barracks, Along Lagos-Kaduna Road, Rafi Lga, Kagara Dirin-Daji/Tungan Magajiya Road, Junction, Rijau Anguwan Chika- Kuta, Near Lag Secretariat, Gussoroo Road, Kuta Along Suleja Minna Road, Opp. Suleman Barau Technical Collage, Kwamba Beside The Div. Off. Station, Along Kaduna-Abuja Express Road, Sabo-Wuse, Tafa Lga Women Centre, Behind Magistration Court, Along Lemu-Gida Road, Wushishi. Along Leg Road, Opp. Baband Abo Primary/Junior Secondary Schoo, Near Divisional Police Station, Maikunkele, Bosso Lga. -

Surviving Works: Context in Verre Arts Part One, Chapter One: the Verre

Surviving Works: context in Verre arts Part One, Chapter One: The Verre Tim Chappel, Richard Fardon and Klaus Piepel Special Issue Vestiges: Traces of Record Vol 7 (1) (2021) ISSN: 2058-1963 http://www.vestiges-journal.info Preface and Acknowledgements (HTML | PDF) PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre (HTML | PDF) Chapter 2 Documenting the early colonial assemblage – 1900s to 1910s (HTML | PDF) Chapter 3 Documenting the early post-colonial assemblage – 1960s to 1970s (HTML | PDF) Interleaf ‘Brass Work of Adamawa’: a display cabinet in the Jos Museum – 1967 (HTML | PDF) PART TWO ARTS Chapter 4 Brass skeuomorphs: thinking about originals and copies (HTML | PDF) Chapter 5 Towards a catalogue raisonnée 5.1 Percussion (HTML | PDF) 5.2 Personal Ornaments (HTML | PDF) 5.3 Initiation helmets and crooks (HTML | PDF) 5.4 Hoes and daggers (HTML | PDF) 5.5 Prestige skeuomorphs (HTML | PDF) 5.6 Anthropomorphic figures (HTML | PDF) Chapter 6 Conclusion: late works ̶ Verre brasscasting in context (HTML | PDF) APPENDICES Appendix 1 The Verre collection in the Jos and Lagos Museums in Nigeria (HTML | PDF) Appendix 2 Chappel’s Verre vendors (HTML | PDF) Appendix 3 A glossary of Verre terms for objects, their uses and descriptions (HTML | PDF) Appendix 4 Leo Frobenius’s unpublished Verre ethnological notes and part inventory (HTML | PDF) Bibliography (HTML | PDF) This work is copyright to the authors released under a Creative Commons attribution license. PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre Predominantly living in the Benue Valley of eastern middle-belt Nigeria, the Verre are one of that populous country’s numerous micro-minorities. -

The Legacy of Baale Irefin Ogundeyi (1912-1914)

- 1 - A) BACKGROUND HISTORY: Ogunlade from Owu was the father of Irefin Ogundeyi according to the family record dated 8/8/61. Kigbati Ogunlade came to Ibadan in the 19th century to join other Owus in the city with his wife. He came with his wife, his inlaw called Idowu. Others were, Adeola, an herbalist (Babalawo) and Ojo Ojawkondo who were friends to his wife. He also brought the father of Gbangbasa the father of Babajide. After the death of Ogunlade, his son Irefin Ogundeyi brought the father of Olaogun to Ibadan after the Kiriji war on arrival at Osogbo. Anisere also followed Irefin Ogunlade to Ibadan and handed him over to Aborisade of the same mother. According to the family, in 2017, Balogun Oderinlo allocated the land at Oke- Ofa to Pa Ogunlade and his son where Irefin Ogundeji built a beautiful palace. Irefin as Ekerin was then overlord of Gbongan town. Other chieftaincy titles of Irefin Ogundeyi from 1895 before he rose to the highest pinnacle of Baale of Ibadan (1912- 1914). His progressive chieftaincy rise was as follow: 1. When Osuntoki was the baale between 1895-1897 Irefin was the Asaju Baale 2. The same position when Fajinmi was Baale between 1897-1902 Irefin was Asaju Baale 3. When Captain F.C. Fuller in 1897 constituted the first members of the council, Irefin was not there. Members were: 1. Fajinmi - Baale 1. Akintola - Balogun 2. Mosaderin - Otun Baale 2. Bablola - Otun Balogun 3. Ogungbesan - Osi Baale 3. Kongi - Osi Balogun 4. Dada - Ekerin Baale 4. Apampa - Asipa Balogun 5. -

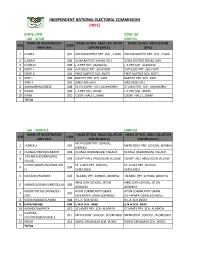

State: Oyo Code: 30 Lga : Afijio Code: 01 Name of Registration Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: OYO CODE: 30 LGA : AFIJIO CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ILORA I 001 OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA 2 ILORA II 002 ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. 3 ILORA III 003 L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. 4 FIDITI I 004 CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI 5 FIDITI II 005 FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI 6 AWE I 006 BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE 7 AWE II 007 AWE HIGH SCH. AWE HIGH SCH. 8 AKINMORIN/JOBELE 008 ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN 9 IWARE 009 L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. 10 IMINI 010 COURT HALL 1, IMINI COURT HALL 1, IMINI TOTAL LGA : AKINYELE CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) CENTRE (RACC) METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, 1 IKEREKU 001 METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, IKEREKU IKEREKU 2 OLANLA/OBODA/LABODE 002 OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE EOLANLA (OGBANGAN) 3 003 COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE VILLAG OLODE/AMOSUN/ONIDUND ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, 4 004 U ONIDUNDU ONIDUNDU 5 OJO-EMO/MONIYA 005 ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN 6 AKINYELE/ISABIYI/IREPODUN 006 AGBAKIN AGBAKIN IWOKOTO/TALONTAN/IDI- AYUN COMMUNITY GRAM. -

A Case Study of Amo Farms, AWE AFIJIO, Oyo State Onosemuode Christopher1, Abodurin Wasiu Adeyemi1

The Use of Geoinformtics in Site Selection for Suitable Landfill for Poultry Waste: A Case Study of Amo Farms, AWE AFIJIO, Oyo State Onosemuode Christopher1, Abodurin Wasiu Adeyemi1 1Department of Environmental Science, College of Sciences, Federal University of Petroleum Resources, Effurun ABSTRACT: This study focused on selection of suitable landfill site for poultry waste in Amo farms Nigeria Limited Awe, Afijio Local Government. The data sets used for the study include; Satellite imagery (Landsat) and topographic maps of the study area. The layers created include those for roads, water bodies, farm sites and the slope map of the study area to determine the degree of slope. The various created layers were subjected to buffering, overlay and query operations using ArcGis 9.3 alongside the established criteria for poultry waste site selection. At the end of the analytical processes, search query was used to generate two most suitable sites of an area that is less than or equal to 20,000m2 (2 hectares). Keywords: Poultry, waste, Site, Geoinformatics, Selection INTRODUCTION is need for both private and public authorities to build up efforts at managing the various wastes generated Disposal sites in some developing countries Nigeria by these various agricultural set-ups. In order to do inclusive are usually not selected in line with this, GIS plays a leading role in selecting suitable established criteria aimed at safeguarding the location for waste disposal sites based on its planning environment and public health. Refuse dumps are and operations that are highly dependent on spatial sited indiscriminately without adequate hydro- data. Generally speaking, GIS plays a key role in geological and geotechnical considerations. -

Ningi Raids and Slavery in Nineteenth Century Sokoto Caliphate

SLAVERY AND ABOLITION A Journal of Comparative Studies Edilorial Advisory Boord · RogerT. Anstey (Kent) Ralph A. Austen (Chicago) Claude Meillassoux (Paris) David Brion Davis (Yale) Domiltique de Menil (Menil ~O'LIlmllllllll Carl N. Degler (Stanford) Suzanne Miers (Ohio) M.1. Finley (Cambridge) Joseph C. Miller (Virginia) Jan Hogendorn (Colby) Orlando Patterson (Harvard) A. G. Hopkins (Birmingham) Edwin Wolf 2nd (Library Co. of Winthrop D. Jordan (Berkeley) Philadelphia) Ion Kenneth Maxwell (Columbia) Edit"': Associate Ediwr: John Ralph Willis (Princeton) C. Duncan Rice (Hamilton) Volume 2 Number 2 September 1981 .( deceased) Manusc ripts and all editorial correspondence and books for review should be Tuareg Slavery and the Slave Trade Priscill a Elle n Starrett 83 (0 Professor John Ralph Willis, Near Eastern Studies Department, Prince. University , Princeton, New Jersey 08540. ~in gi Raids and Slave ry in Nineteenth Articles submiued [0 Slavery and Abolilion are considered 0t:\ the understanding Centu ry Sokoto Ca liphate Adell Patton, Jr. 114 they are not being offered for publication elsewhere , without the exp ressed cO losenll the Editor. Slavery: Annual Bibliographical Advertisement and SUbscription enquiries should be sent to Slavery and IIbol"'", Supplement (198 1) Joseph C. Miller 146 Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., Gainsborough House, II Gainsborough London Ell IRS. The Medallion on the COVel" is reproduced by kind perm.ission of Josiah W"dgwoocU Sons Ltd. © Frank Cass & Co. Ltd. 1981 All rigllt! ,eseroed. No parr of his publication may be reprodU4ed. siored in 0 retrieval sysu.. lJ'anmliJt~d in anyfarm. or by any ,"eal'lJ. eUclJ'onic. rMchonicoJ. phalocopying. recording. or without tlu pn·or permissicm of Frank Call & Co. -

An Atlas of Nigerian Languages

AN ATLAS OF NIGERIAN LANGUAGES 3rd. Edition Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road, Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone 00-44-(0)1223-560687 Mobile 00-44-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Skype 2.0 identity: roger blench i Introduction The present electronic is a fully revised and amended edition of ‘An Index of Nigerian Languages’ by David Crozier and Roger Blench (1992), which replaced Keir Hansford, John Bendor-Samuel and Ron Stanford (1976), a pioneering attempt to synthesize what was known at the time about the languages of Nigeria and their classification. Definition of a Language The preparation of a listing of Nigerian languages inevitably begs the question of the definition of a language. The terms 'language' and 'dialect' have rather different meanings in informal speech from the more rigorous definitions that must be attempted by linguists. Dialect, in particular, is a somewhat pejorative term suggesting it is merely a local variant of a 'central' language. In linguistic terms, however, dialect is merely a regional, social or occupational variant of another speech-form. There is no presupposition about its importance or otherwise. Because of these problems, the more neutral term 'lect' is coming into increasing use to describe any type of distinctive speech-form. However, the Index inevitably must have head entries and this involves selecting some terms from the thousands of names recorded and using them to cover a particular linguistic nucleus. In general, the choice of a particular lect name as a head-entry should ideally be made solely on linguistic grounds.