Chapter Two Towards Huangshan— the Early Paintings of Huang Binhong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian

Macalester International Volume 18 Chinese Worlds: Multiple Temporalities Article 12 and Transformations Spring 2007 Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian Desheng Fang Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl Recommended Citation Qian, Zhuzhong and Fang, Desheng (2007) "Towards Chinese Calligraphy," Macalester International: Vol. 18, Article 12. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol18/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Global Citizenship at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester International by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Towards Chinese Calligraphy Qian Zhuzhong and Fang Desheng I. History of Chinese Calligraphy: A Brief Overview Chinese calligraphy, like script itself, began with hieroglyphs and, over time, has developed various styles and schools, constituting an important part of the national cultural heritage. Chinese scripts are generally divided into five categories: Seal script, Clerical (or Official) script, Regular script, Running script, and Cursive script. What follows is a brief introduction of the evolution of Chinese calligraphy. A. From Prehistory to Xia Dynasty (ca. 16 century B.C.) The art of calligraphy began with the creation of Chinese characters. Without modern technology in ancient times, “Sound couldn’t travel to another place and couldn’t remain, so writings came into being to act as the track of meaning and sound.”1 However, instead of characters, the first calligraphy works were picture-like symbols. These symbols first appeared on ceramic vessels and only showed ambiguous con- cepts without clear meanings. -

Sustainable Tourism in China

6th UNWTO Executive Training Program, Bhutan Sustainable Tourism Observatories and Cases in China Prof. BAO Jigang, Ph. D Assistant President, Dean of School of Tourism Management, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, P. R. China Email:[email protected] 25th - 28th, June, 2012 Content Part I: Observatories for Sustainable Tourism Development in China; Part II: Indicators for Sustainable Tourism Development in Yangshuo, China; Part III: Chinese Sustainable Tourism Cases(Some positive and negative examples) Observatories for Sustainable Part I Tourism Development in China Introduction The Observatory for Sustainable Tourism development in China In July 2005, the workshop of “UNWTO Indictors for Sustainable Tourism” was held in Yangshuo, Guilin, China. Yangshou Observatory for Sustainable Tourism Development was founded in 2005. The conference of UNWTO indicators for Sustainable Tourism The Destinations as Cases for Sustainable Tourism Development in China In March 2008, the Observatory for Sustainable Tourism Development in Huangshan Mountain was established. Opening Ceremony of the Observatory for Sustainable Centre for Tourism Planning & Tourism Development in Huangshan Mountain Research , Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China, takes the responsibility to monitor the indicators for sustainable tourism in Huangshan Mountain . Observatory for Sustainable Tourism Development in Huangshan Mountain The Destinations as Cases for Sustainable Tourism Development in China Collaboration Agreement between UNWTO and Sun Yat-Sen University -

Dengfeng Observatory, China

90 ICOMOS–IAU Thematic Study on Astronomical Heritage Archaeological/historical/heritage research: The Taosi site was first discovered in the 1950s. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, archaeologists excavated nine chiefly tombs with rich grave goods, together with large numbers of common burials and dwelling foundations. Archaeologists first discovered the walled towns of the Early and Middle Periods in 1999. The remains of the observatory were first discovered in 2003 and totally uncovered in 2004. Archaeoastronomical surveys were undertaken in 2005. This work has been published in a variety of Chinese journals. Chinese archaeoastronomers and archaeologists are currently conducting further collaborative research at Taosi Observatory, sponsored jointly by the Committee of Natural Science of China and the Academy of Science of China. The project, which is due to finish in 2011, has purchased the right to occupy the main field of the observatory site for two years. Main threats or potential threats to the sites: The most critical potential threat to the observatory site itself is from the burials of native villagers, which are placed randomly. The skyline formed by Taer Hill, which is a crucial part of the visual landscape since it contains the sunrise points, is potentially threatened by mining, which could cause the collapse of parts of the top of the hill. The government of Xiangfen County is currently trying to shut down some of the mines, but it is unclear whether a ban on mining could be policed effectively in the longer term. Management, interpretation and outreach: The county government is trying to purchase the land from the local farmers in order to carry out a conservation project as soon as possible. -

Natural History Connects Medical Concepts and Painting Theories In

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 Natural history connects medical concepts and painting theories in China Sara Madeleine Henderson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Henderson, Sara Madeleine, "Natural history connects medical concepts and painting theories in China" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 1932. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1932 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATURAL HISTORY CONNECTS MEDICAL CONCEPTS AND PAINTING THEORIES IN CHINA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Sara Madeleine Henderson B.A., Smith College, 2001 August 2007 Dedicated to Aunt Jan. Janice Rubenstein Sachse, 1908 - 1998 ii Preface When I was three years old my great-aunt, Janice Rubenstein Sachse, told me that I was an artist. I believed her then and since, I have enjoyed pursuing that goal. She taught me the basics of seeing lines in nature; lines formed on the contact of shadow and light, as well as organic shapes. We also practiced blind contour drawing1. I took this exercise very seriously then, and I have reflected upon these moments of observation as I write this paper. -

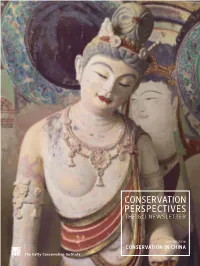

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION MOUNT SANQINGSHAN NATIONAL PARK (CHINA) – ID No. 1292

WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION – IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION MOUNT SANQINGSHAN NATIONAL PARK (CHINA) – ID No. 1292 1. DOCUMENTATION i) Date nomination received by IUCN: April 2007 ii) Additional information offi cially requested from and provided by the State Party: IUCN requested supplementary information on 14 November 2007 after the fi eld visit and on 19 December 2007 after the fi rst IUCN World Heritage Panel meeting. The fi rst State Party response was offi cially received by the World Heritage Centre on 6 December 2007, followed by two letters from the State Party to IUCN dated 25 January 2008 and 28 February 2008. iii) UNEP-WCMC Data Sheet: 11 references (including nomination document) iv) Additional literature consulted: Dingwall, P., Weighell, T. and Badman, T. (2005) Geological World Heritage: A Global Framework Strategy. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland; Hilton-Taylor, C. (compiler) (2006) IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland; IUCN (ed.) (2006) Enhancing the IUCN Evaluation Process of World Heritage Nominations: A Contribution to Achieving a Credible and Balanced World Heritage List. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland; Management Committee (2007) Abstract of the Master Plan of Mount Sanqingshan National Park. Mount Sanqingshan National Park; Management Committee (2007) Mount Sanqingshan International Symposium on Granite Geology and Landscapes. Mount Sanqingshan National Park; Migon, P. (2006) Granite Landscapes of the World. Oxford University Press; Migon, P. (2006) Sanqingshan – The Hidden Treasure of China. Available online; Peng, S.L., Liao, W.B., Wang, Y.Y. et al. (2007) Study on Biodiversity of Mount Sanqingshan in China. Science Press, Beijing; Shen, W. (2001) The System of Sacred Mountains in China and their Characteristics. -

Art of the Mountain

Wang Wusheng, Disciples of Buddha and Fairy Maiden Peak, taken at Peak Lying on the Clouds June 2004, 8 A.M. ART OF THE MOUNTAIN THROUGH THE CHINESE PHOTOGRAPHER’S LENS Organized by China Institute Gallery Curated by Willow Weilan Hai, Jerome Silbergeld, and Rong Jiang A traveling exhibition available through summer 2023 ART OF THE MOUNTAIN: THROUGH THE CHINESE PHOTOGRAPHER’S LENS Organized by China Institute Gallery Curated by Willow Weilan Hai, Jerome Silbergeld, and Rong Jiang A traveling exhibition available through summer 2023 In Chinese legend, mountains are the pillars that hold up the sky. Mountains were seen as places that nurture life. Their veneration took the form of rituals, retreat from social society, and aesthetic appreciation with a defining role in Chinese art and culture. Art of the Mountain will consist of three sections: Revered Mountains of China will introduce the geography, history, legends, and culture that are associated with Chinese mountains and will include photographs by Hou Heliang, Kang Songbai and Kang Liang, Li Daguang, Lin Maozhao, Li Xueliang, Lu Hao, Zhang Anlu, Xiao Chao, Yan Shi, Wang Jing, Zhang Jiaxuan, Zhang Huajie, and Zheng Congli. Landscape Aesthetics in Photography will present Wang Wusheng’s photography of Mount Huangshan, also known as Yellow Mountain, to reflect the renowned Chinese landscape painting aesthetic and its influence. New Landscape Photography includes the works of Hong Lei, Lin Ran, Lu Yanpeng, Shao Wenhuan, Taca Sui, Xiao Xuan’an, Yan Changjiang, Yang Yongliang, Yao Lu, Zeng Han, Gao Hui, and Feng Yan, who express their thoughts on the role of mountains in society. -

Ni Zan in Oxford Art Online

Ni Zan in Oxford Art Online http://www.oxfordartonline.com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/subs... Oxford Art Online Grove Art Online Ni Zan article url: http://www.oxfordartonline.com:80/subscriber/article/grove/art/T062602 Ni Zan [Ni Tsan; zi Yuanzhen; hao Yunlin] (b Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, 1301; d 1374). Chinese painter and calligrapher. He is designated one of the Four Masters of the Yuan (1279–1368), with HUANG GONGWANG, WU ZHEN and WANG MENG. Ni Zan’s family were of Xixia (Tangut) origin. His tenth-generation ancestor Shi came to China as Xixia ambassador in 1034–7 at the time of Emperor Renzong (reg 1023–63), and the family settled in Duliang (modern Anhui Province). In 1127–30, under Emperor Gaozong (reg 1127–62), Ni Zan’s fifth-generation ancestor Yi moved south with the Southern Song (1127–1279), settling at Zhituo village in Wuxi, modern Jiangsu Province, where the Ni family prospered. Ni Zan and his elder brother Ying were the sons of a concubine, Yan. Their father died when they were young, and they were raised by their eldest half-brother, Ni Zhaogui (1279–1328). Ying was mentally incompetent, and after Zhaogui’s death Ni Zan assumed responsibility for the family estate, a role ill-suited to his natural inclinations. He led a privileged and secluded home life for 20 or more years; in the mid-1340s he spent most of his time among rare books, antique paintings, calligraphy and flowers in his favourite studio, the Qingbi ge (‘Pure and secluded pavilion’). Ni Zan was an ardent admirer of the great Northern Song (1127–1279) artist and connoisseur, MI FU, and shared two of his idiosyncrasies: fastidiousness and generosity. -

3 Days Datong Pingyao Classical Tour

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 3 days Datong Pingyao classical tour https://windhorsetour.com/datong-pingyao-tour/datong-pingyao-classical-tour Datong Pingyao Exploring the highlights of Datong and Pingyao's World Culture Heritage sites gives you a chance to admire the superb artistic attainments of the craftsmen and understand the profound Chinese culture in-depth. Type Private Duration 3 days Theme Culture and Heritage, Family focused, Winter getaways Trip code DP-01 Price From € 304 per person Itinerary This is a 3 days’ culture discovery tour offering the possibility to have a glimpse of the profound culture of Datong and Pingyao and the outstanding artistic attainments of the craftsmen of ancient China in a short time. The World Cultural Heritage Site - Yungang Grottoes, Shanhua Monastery, Hanging Monastery, as well as Yingxian Wooden Pagoda gives you a chance to admire the rich Buddhist culture of ancient China deeply. The Pingyao Ancient City, one of the 4 ancient cities of China and a World Cultural Heritage site, displays a complete picture of the prosperity of culture, economy, and society of the Ming and Qing Dynasties for tourists. Day 01 : Datong arrival - Datong city tour Arrive Datong in the early morning, your experienced private guide, and a comfortable private car with an experienced driver will be ready (non-smoking) to serve for your 3 days ancient China discovery starts. The highlights today include Shanhua Monastery, Nine Dragons Wall, as well as Yungang Grottoes. Shanhua Monastery is the largest and most complete existing monastery in China. The Nine Dragons Wall in Datong is the largest Nine Dragons Wall in China, which embodies the superb carving skills of ancient China. -

A Comparison of the Paintings of Bada Shanren and Shitao of the Qing Dynasty

A Comparison of the Paintings of Bada Shanren and Shitao of the Qing Dynasty Liu HONG, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University 1. The respective backgrounds of Bada Shanren and Shitao Bada Shanren, the last and best known of many names used by Zhuda (1626- 1705/6), was a member of the royal household in the Ming Dynasty before he became a monk in 1644. Shitao was also a Ming prince who had grand stature as a painter. Fifteen years or so younger than Bada Shanren, Shitao was born probably between 1638 and 1641 and died possibly before 1720 (Loehr, 1980, p. 299 and 302). Both Bada Shanren and Shitao were forced to be monks and lived poor lives after the extinction of the Ming Dynasty. Due to their misfortunes, they both suffered great pains during their remaining years, which had a great influence on their paintings. Although Bada Shanren was famous when he was alive, his only artist friend was Shitao (Cai & Xu, 1998). Despite their common backgrounds and mutual understanding, their paintings display a considerable amount of differences because of their divergent characteristics and attitudes toward life. In this essay, I will discuss the similarities and differences between their artwork through some painting examples, and give my own interpretations. Inscribe: A journal of undergraduate student writing in and about Asia 1 Figure 1 Figure 2 Autumn Eagle Eagle Painted by Painted by Bada Shitao Shanren An eagle An eagle standing on a standing on tree is staring rock, with a at two magpies pine tree which are nearby. flying away. -

The Daoist Tradition Also Available from Bloomsbury

The Daoist Tradition Also available from Bloomsbury Chinese Religion, Xinzhong Yao and Yanxia Zhao Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed, Yong Huang The Daoist Tradition An Introduction LOUIS KOMJATHY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 175 Fifth Avenue London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10010 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com First published 2013 © Louis Komjathy, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Louis Komjathy has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author. Permissions Cover: Kate Townsend Ch. 10: Chart 10: Livia Kohn Ch. 11: Chart 11: Harold Roth Ch. 13: Fig. 20: Michael Saso Ch. 15: Fig. 22: Wu’s Healing Art Ch. 16: Fig. 25: British Taoist Association British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 9781472508942 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Komjathy, Louis, 1971- The Daoist tradition : an introduction / Louis Komjathy. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4411-1669-7 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-6873-3 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-9645-3 (epub) 1. -

Imperial Mobility and the Kangxi Emperor's Construction Of

Investigating things under Heaven: imperial mobility and the Kangxi emperor’s construction of knowledge Catherine Jami To cite this version: Catherine Jami. Investigating things under Heaven: imperial mobility and the Kangxi emperor’s construction of knowledge. Individual itineraries and the Spatial Dynamics of Knowledge: Science, Technology and Medicine in China, 17th-20th centuries, Collège de France, pp.173-205, 2017, 978-2- 85757-077-6. halshs-02319149 HAL Id: halshs-02319149 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02319149 Submitted on 24 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. BIBLIOTHÈQUE DE L’INSTITUT DES HAUTES ÉTUDES CHINOISES VOLUME XXXIX INDIVIDUAL ITINERARIES AND THE SPATIAL DYNAMICS OF KNOWLEDGE SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND MEDICINE IN CHINA, 17TH-20TH CENTURIES EDITED BY Catherine JAMI PARIS — 2017 COLLÈGE DE FRANCE INSTITUT DES HAUTES ÉTUDES CHINOISES 5 INVESTIGATING THINGS UNDER HEAVEN: IMPERIAL MOBILITY AND THE KANGXI EMPEROR’S CONSTRUCTION OF KNOWLEDGE Catherine JAMI During the late imperial period, emperors played a major role in the pro- duction and circulation of knowledge in China. From the early fifteenth century, they promoted the teachings of the Cheng-Zhu school of philoso- phy (named after the Song dynasty philosophers Cheng Yi 程頤 [1033- 1107] and Zhu Xi 朱熹 [1130-1200]) and its interpretation of the Confucian teachings to the status of state orthodoxy, a status retained for almost five centuries, until the end of the imperial examination system.