Legal Information and the Search for Cognitive Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

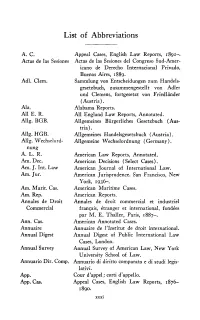

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations A. C. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, r8gr-. Aetas de las Sesiones Aetas de las Sesiones del Congreso Sud-Amer icano de Derecho Internacional Privado, Buenos Aires, r88g. Adl. Clem. Sammlung von Entscheidungen zum Handels gesetzbuch, zusammengestellt von Adler und Clemens, fortgesetzt von Friedlander (Austria). Ala. Alabama Reports. All E. R. All England Law Reports, Annotated. Allg. BGB. Allgemeines Biirgerliches Gesetzbuch (Aus- tria). Allg. HGB. Allgemeines Handelsgesetzbuch (Austria). All g. W echselord- Allgemeine Wechselordnung (Germany). nung A. L. R. American Law Reports, Annotated. Am. Dec. American Decisions ( Select Cases) . Am. J. Int. Law American Journal of International Law. Am. Jur. American Jurisprudence. San Francisco, New York, 1936-. Am. Marit. Cas. American Maritime Cases. Am. Rep. American Reports. Annales de Droit Annales de droit commercial et industriel Commercial fran~ais, etranger et international, fondees par M. E. Thaller, Paris, r887-. Ann. Cas. American Annotated Cases. Annuaire Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international. Annual Digest Annual Digest of Public International Law Cases, London. Annual Survey Annual Survey of American Law, New York University School of Law. Annuario Dir. Camp. Annuario di diritto comparato e di studi legis lativi. App. Cour d'appel; corti d'appello. App. Cas. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, 1876- r8go. xxxi XXXll LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS App. D.C. Appeal Cases, District of Columbia. App. Div. New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division Reports. Arch. Civ. Prax. Archiv fiir die civilistische Praxis (Germany) . Arch. Jud. Archivo judiciario (Brazil). Ariz. Arizona Reports. Ark. Arkansas Reports. Asp. Marit. Cas. Aspinall's Maritime Cases. Atl. Atlantic Reporter, National Reporter System (United States). -

Research Guide

Research Guide FINDING CASES I. HOW TO FIND A CASE WHEN YOU KNOW THE CITATION A. DECIPHERING LEGAL CITATIONS 1. CASE CITATIONS A case citation includes: the names of the parties, the volume number of the case reporter, the abbreviated name of the reporter, the page number where the case can be found, and the year of the decision. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800 (1982). Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta = names of the parties 30 = volume number of the case reporter Cal. = abbreviated name of the case reporter, California Reports 3d = series number of the case reporter, California Reports 800 = page number of the case reporter (1982) = year of the decision 2. ABBREVIATIONS OF REPORTER NAMES The abbreviations used in citations can be deciphered by consulting: a. Prince’s Bieber Dictionary of Legal Abbreviations, 6th ed. (Ref. KF 246 .p74 2009) b. Black's Law Dictionary (Ref. KF 156 .B624 2009). This legal dictionary contains a table of abbreviations. Copies of Black's are located on dictionary stands throughout the library, as well as in the Reference Collection. 3. REPORTERS AND PARALLEL CITATIONS A case may be published in more than one reporter. Parallel citations indicate the different reporters publishing the same case. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800, 180 Cal. Rptr. 628, 640 P.2d 764 (1982). 02/08/12 (Rev.) RG14 (OVER) This case will be found in three places: the "official" California Reports 3d (30 Cal. 3rd 800); and the two "unofficial" West reporters: the California Reporter (180 Cal. -

Handbook on Briefs and Oral Arguments

HANDBOOK ON BRIEFS AND ORAL ARGUMENTS by THE HON. ROBERT E. DAVISON and DAVID P. BERGSCHNEIDER ©2007 by the Office of the State Appellate Defender. All rights reserved. Updated 2020 by: Kerry Bryson & Shawn O’Toole, Deputy State Appellate Defenders State Appellate Defender Offices Administrative Office Third District Office 400 West Monroe - Suite 202 770 E. Etna Road Springfield, Illinois 62705 Ottawa, Illinois 61350 Phone: (217) 782-7203 Phone: (815) 434-5531 Fax: (217) 782-5385 Fax: (815) 434-2920 First District Office Fourth District Office 203 N. LaSalle, 24th Floor 400 West Monroe - Suite 303 Chicago, Illinois 60601 Springfield, Illinois 62705-5240 Phone: (312) 814-5472 Phone: (217) 782-3654 Fax: (312) 814-1447 Fax: (217) 524-2472 Second District Office Fifth District Office One Douglas Avenue, 2nd Floor 909 Water Tower Circle Elgin, Illinois 60120 Mount Vernon, Illinois 62864 Phone: (847) 695-8822 Phone: (618) 244-3466 Fax: (847) 695-8959 Fax: (618) 244-8471 Juvenile Defender Resource Center 400 West Monroe, Suite 202 Springfield, Illinois 62704 Phone: (217) 558-4606 Email: [email protected] i INTRODUCTION The first edition of this Handbook was written in the early 1970's by Kenneth L. Gillis, who went on to become a Circuit Court Judge in Cook County. The Handbook was later expanded by Robert E. Davison, former First Assistant Appellate Defender and Circuit Court Judge in Christian County. Although the Handbook has been updated on several occasions, the contributions of Judges Gillis and Davison remain an essential part. The lawyers who use this Handbook are encouraged to offer suggestions for improving future editions. -

Legal Research 1 Ll.M

LEGAL RESEARCH 1 LL.M. Legal Research PRELIMINARIES Legal Authority • Legal Authority can be… • Primary—The Law Itself • Secondary—Commentary about the law Four Main Sources of Primary Authority . Constitutions Establishes structure of the government and fundamental rights of citizens . Statutes Establishes broad legislative mandates . Court Opinions (also called Cases) Interprets and/or applies constitution, statutes, and regulations Establishes legal precedent . Administrative Regulations Fulfills the legislative mandate with specific rules and enforcement procedures Primary Sources of American Law United States Constitution State Constitutions Executive Legislative Judicial Executive Legislative Judicial Regulations Statutes Court Opinions Regulations Statutes Court Opinions (Cases) (Cases) Federal Government State Government Civil Law Common Law Cases • Illustrate or • Interpret exemplify code. statutes • Not binding on • Create binding third parties precedent Statutes (codes) • Very specific • Broader and and detailed more vague French Intellectual Property Code Cases interpret statutes: Parody, like other comment and criticism, may claim fair use. Under the first of the four § 107 factors, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature ...,” the enquiry focuses on whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or whether and to what extent it is “transformative,” altering the original with new expression, meaning, or message. The more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use. The heart of any parodist's claim to quote from existing material is the use of some elements of a prior author's composition to create a new one that, at least in part, comments on that author's work. -

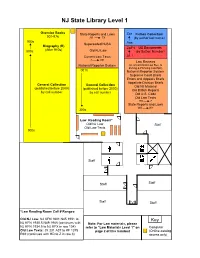

NJ State Library Level 1

NJ State Library Level 1 Oversize Books State Reports and Laws Zzz Fiction Collection 001-976 AK TX (by author last name) 900s Superseded NJSA Aaa Biography (B) Zp/P4 US Documents (After 910s) 800s Old NJ Law (by SuDoc Number) Current Law Texts A1.1 A KE Law Reviews National Reporter System (U. of Cincinnati Law Rev. to Zoning & Planning Law Rpt.) 001s National Reporter System Supreme Court Briefs Errors and Appeals Briefs Appellate Division Briefs General Collection General Collection Old NJ Material (published before 2000) (published before 2000) Old British Reports by call number by call number Old U.S. Code Old Law Texts HD Z State Reports and Laws WA WY 300s Law Reading Room* Old NJ Law Staff Old Law Texts 300s Staff Staff Staff Staff Staff *Law Reading Room Call # Ranges: Old NJ Law: NJ KFN 1801 N45 1981 to Key NJ KFN 1930.5 N49 1988 (continues with Note: For Law materials, please NJ KFN 1934.5 to NJ KFX in row 104) refer to “Law Materials Level 1” on Computer Old Law Texts: JX 231 A37 to KF 1375 page 2 of this handout (Online-catalog R69 (continues with HD to Z in row 3) access only) Law Materials Level 1 Title Row Title Row Alabama Reports and Session Laws 107 NJ Forms Legal and Business 11 Alaska Reports and Session Laws 107 NJ Law Journal 119 Alcoholic Beverage Control 12 NJ Law Reports 10 American Digest 99 NJ Law Times Reporter 10 American Jurisprudence 99 NJ Laws 11 Arizona Reports and Session Laws 107 NJ Legislative Index 11 Arkansas Reports and Session Laws 107, 108 NJ Misc. -

Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law Peter W

Cornell Law Library Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship Spring 2011 Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law Peter W. Martin Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Courts Commons, Legal Writing and Research Commons, and the Science and Technology Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Peter W., "Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law" (2011). Cornell Law Faculty Publications. Paper 1197. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/1197 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE JOURNAL OF APPELLATE PRACTICE AND PROCESS ARTICLES ABANDONING LAW REPORTS FOR OFFICIAL DIGITAL CASE LAW* Peter W. Martin** I. INTRODUCTION Like most states Arkansas entered the twentieth century with the responsibility for case law publication imposed by law on a public official lodged within the judicial branch. The "reporter's" office was then, as it is still today, a "constitutional" one.' Title and role reach all the way back to Arkansas's * Q Peter W. Martin, 2011. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 543 Howard Street, 5th Floor, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. -

Mandatory V. Persuasive Cases

TEACHABLE MOMENTS FOR STUDENTS… 8383 PERSPECTIVES regulations, administrative agency decisions, MANDATORY V. executive orders, and treaties. Secondary authority, PERSUASIVE CASES basically, is everything else: articles, Restatements, treatises, commentary, etc. The most useful While decision BY BARBARA BINTLIFF authority addresses your legal issue and is close to “ your factual situation. While decision makers are makers are Barbara Bintliff is Director of the Law Library and usually willing to accept guidance from a wide Associate Professor of Law at the University of Colorado range of sources, only a primary authority can be usually willing in Boulder. She is also a member of the Perspectives mandatory in application. Editorial Board. Just because an authority is primary, however, to accept Teachable Moments for Students ... is does not automatically make its application in a designed to provide information that can be used for given situation mandatory. Some primary author- guidance from quick and accessible answers to the basic questions ity is only persuasive. The proper characterization that are frequently asked of librarians and those of a primary authority as mandatory or persuasive a wide range involved in teaching legal research and writing. is crucial to any proceeding; it can make the differ- These questions present a “teachable moment,” a ence between success and failure for a client’s of sources, brief window of opportunity when-—because he or cause. This is true of all primary authority, but this she has a specific need to know right now—the column will address case authority only. only a primary student or lawyer asking the question may actually Determining when a court’s decision is manda- remember the answer you provide. -

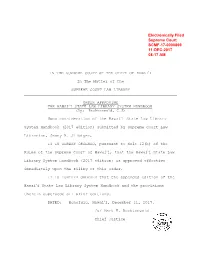

Hawaiʻi State Law Library System Handbook

Electronically Filed Supreme Court SCMF-17-0000869 11-DEC-2017 08:17 AM IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF HAWAI#I In The Matter of the SUPREME COURT LAW LIBRARY ORDER APPROVING THE HAWAI#I STATE LAW LIBRARY SYSTEM HANDBOOK (By: Recktenwald, C.J) Upon consideration of the Hawai#i State Law Library System Handbook (2017 edition) submitted by Supreme Court Law Librarian, Jenny R. Silbiger, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED, pursuant to Rule 12(b) of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Hawai#i, that the Hawai#i State Law Library System Handbook (2017 edition) is approved effective immediately upon the filing of this order. IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the appended edition of the Hawai#i State Law Library System Handbook and the provisions therein supersede all prior editions. DATED: Honolulu, Hawai#i, December 11, 2017. /s/ Mark E. Recktenwald Chief Justice Hawai‘i State Law Library System Handbook Revised September 2017 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Locations and Contact Information …………………………………………………….……………... 2 Security ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Library Hours ……………………………………………………………………………………….…… 3 Accommodations for Patrons with Disabilities ………………………………………………….…… 3 Collections …………………………………………………………………………………………….… 3 Online Public Access Catalog (OPAC) ………………………………………………………….…… 3 Borrowing Privileges ………………………………………………………………………………….... 4 Reference Services …………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Electronic Resources …………………………………………………………………………………... 4 Public Computers …………………………………………………………………………………....... -

How to Locate a Case Using a Digest

Sacramento County Public Law Library 609 9th St. Sacramento, CA 95814 saclaw.org (916) 874-6012 >> Home >> Law 101 DIGESTS How to Locate a Case Using a Digest The Law Library has two sets of West Digests in print format (now published by Thomson Reuters): Table of Contents The United States Supreme Court Digest, used to locate 1. How to Locate a Case Using United States Supreme Court cases, is located in Compact Topic and Key Number System in Shelving next to the Supreme Court Reporter, at KF 101 .1 Westlaw ...................................... 2 U55. Like all digests, each volume in the set is updated 2. Abbreviations and Locations of with pocket parts. Case Reporters ............................ 4 West’s California Digest, located in Row C-9 of Compact Shelving at KFC 57 .W47, is used to locate California Supreme Court and California Appellate Court cases. Digests are arranged alphabetically by topic. Examples of the approximately 400 topics are: Banks and Banking, Franchises, Insurance, Libel and Slander, Partnership, Fraud, and Criminal Law. Each topic is divided into subtopics known as "key numbers." A complete list of topic headings is available in the front of each digest volume. A complete list of key numbers is available at the beginning of each topic. A Quick Reference Guide to West Key Number System is available online west.thomson.com/documentation/westlaw/wlawdoc/wlres/keynmb06.pdf. Locate a topic and key number that interests you by scanning the list of topic headings and key numbers or by using the Descriptive Word Index at the end of each set of digests. -

The Federal Judicial Power and the International Legal Order

CURTIS A. BRADLEY THE FEDERAL JUDICIAL POWER AND THE INTERNATIONAL LEGAL ORDER Richard Falk famously argued that domestic courts should operate as "agents of the international order."1 Recent academic debates over the role of international law in the U.S. legal system, and over the relevance of foreign and international materials in U.S. con- stitutional interpretation, are at least in part debates about this proposition. Modern variants of Falk's claim can be found in the works of scholars such as Harold Koh, Jennifer Martinez, and Anne- Marie Slaughter.' These and other "internationalist" scholars con- sider the U.S. judiciary as part of a "global community of courts," emphasize the values of international cross-fertilization and har- monization, and view international law as directly permeating, and often having primacy within, the U.S. legal system. "Constitution- alist" or "revisionist" scholars, by contrast, distinguish between the international and domestic legal systems, emphasize constitutional structure as a limitation on the domestic effect of international law, and generally advocate political branch rather than judicial control over the domestic implementation of international legal obliga- Curtis A. Bradley is the Richard and Marcy Horvitz Professor of Law at Duke Law School. AUTHOR'S NOTE: Thanks to Kathy Bradley, Jack Goldsmith, Joost Pauwelyn, Eric Posner, Paul Stephan, Carlos Vazquez, Mark Weisburd, and Ernest Young for helpful comments. Richard A. Falk, The Role of Domestic Courts in the InternationalLegal Order 72 (1964). 2 See, e.g., Harold Hongju Koh, TransnationalLegal Process, 75 Neb L Rev 181 (1996); Jennifer Martinez, Towards an InternationalJudicial System, 56 Stan L Rev 429 (2003); Anne-Marie Slaughter, Judicial Globalization, 40 Va J Intl L 1103 (2000). -

William Taylor Muse Law Library University of Richmond School of Law

William Taylor Muse Law Library University of Richmond School of Law Research Guide : Federal Case Law Introduction Case law is the law as evidenced by a written judicial opinion. It is distinguished from statutory or administrative law although it frequently interprets these types of law. A judicial opinion is the expressed reasoning for the conclusion in a certain case. This research guide discusses how to locate federal case law. Although the focus here is on federal cases, the principles utilized to locate federal case law are applicable for locating the case law of a particular state. Basics Publication of opinions — Judicial opinions are published in three stages. The first is in the form of a slip opinion issued and published by the court soon after the decision is handed down. The second stage of publication is known as advance sheets, a portion of opinions that are ultimately published in the same reporter volume. Advance sheets typically contain the volume and page numbers of the future reporter volume. The final stage of publication is the actual reporter volume. The reporter contains several advance sheets bound into a new volume of the respective reporter series. Published v. Unpublished opinions — Not all cases result in judicial opinions that are published. Published opinions are available both online and in hard copy in one of the various series of reporters. — With regard to the federal courts of appeals, only those opinions deemed to have ―general precedential value‖ are designated for publication by the court. As of January 1, 2001, some unpublished opinions of the federal courts of appeals can be located in the Federal Appendix. -

TMLL Guide Chapter 11

CHAPTER 11 RESEARCHING A FEDERAL LAW PROBLEM TABLE OF CONTENTS Federal Government U.S. Constitution Federal Legislation Federal Courts Federal Court Rules Federal Regulations and Other Administrative Materials Strategies for Researching a Federal Law Problem Highlights of Bluebook Form for Federal Authorities Federal Practice Materials Checklist: Researching a Federal Law Problem FEDERAL GOVERNMENT The federal government includes three branches: the executive, legislative, and judicial. The executive is the President. Legislative power is vested with Congress. Congress has two chambers: the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate. The judiciary consists of the Supreme Court of the United States (the highest appellate court in the nation), the circuit courts of appeals (the intermediate appellate courts), district courts (trial courts of general jurisdiction), and various specialty courts. For more information on the structure of the federal government, see the U.S. Government Manual. U.S. CONSTITUTION The U.S. Constitution is the organic law of the United States. It defines and establishes the powers and structure of the federal government and guarantees certain fundamental rights. The United States has had two constitutions in its history, the Articles of Confederation (1777) and the current Constitution (1789) albeit with several amendments. The U.S. Constitution is available in print (in the U.S. Code and other books) and online. Online sources include Bloomberg Law, Lexis, and Westlaw (login required); and freely available at websites such as the Cornell’s Legal Information Institute or Congress.gov. The U.S. Constitution consists of a preamble, several articles, and several amendments. The preamble which begins with the famous phrase “We the people” is generally viewed as being persuasive, but not having legal force.