Researching Judicial Opinions Courtney L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

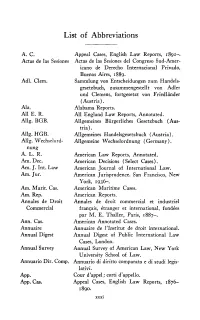

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations A. C. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, r8gr-. Aetas de las Sesiones Aetas de las Sesiones del Congreso Sud-Amer icano de Derecho Internacional Privado, Buenos Aires, r88g. Adl. Clem. Sammlung von Entscheidungen zum Handels gesetzbuch, zusammengestellt von Adler und Clemens, fortgesetzt von Friedlander (Austria). Ala. Alabama Reports. All E. R. All England Law Reports, Annotated. Allg. BGB. Allgemeines Biirgerliches Gesetzbuch (Aus- tria). Allg. HGB. Allgemeines Handelsgesetzbuch (Austria). All g. W echselord- Allgemeine Wechselordnung (Germany). nung A. L. R. American Law Reports, Annotated. Am. Dec. American Decisions ( Select Cases) . Am. J. Int. Law American Journal of International Law. Am. Jur. American Jurisprudence. San Francisco, New York, 1936-. Am. Marit. Cas. American Maritime Cases. Am. Rep. American Reports. Annales de Droit Annales de droit commercial et industriel Commercial fran~ais, etranger et international, fondees par M. E. Thaller, Paris, r887-. Ann. Cas. American Annotated Cases. Annuaire Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international. Annual Digest Annual Digest of Public International Law Cases, London. Annual Survey Annual Survey of American Law, New York University School of Law. Annuario Dir. Camp. Annuario di diritto comparato e di studi legis lativi. App. Cour d'appel; corti d'appello. App. Cas. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, 1876- r8go. xxxi XXXll LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS App. D.C. Appeal Cases, District of Columbia. App. Div. New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division Reports. Arch. Civ. Prax. Archiv fiir die civilistische Praxis (Germany) . Arch. Jud. Archivo judiciario (Brazil). Ariz. Arizona Reports. Ark. Arkansas Reports. Asp. Marit. Cas. Aspinall's Maritime Cases. Atl. Atlantic Reporter, National Reporter System (United States). -

Indiana Law Journal

Indiana Law Journal Volume 10 Issue 5 Article 8 2-1935 Indiana Bar Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation (1935) "Indiana Bar," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 10 : Iss. 5 , Article 8. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol10/iss5/8 This Special Feature is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIANA BAR A Message From the President At the time this message is written (February 2nd) the decision of the Supreme Court on the validity of the Bar Admission Act of 1931 and the method of amending the constitution of Indiana is but a few days old. The removal of the provision of the constitution providing that "every person of good moral character, being a voter, shall be entitled to admission to practice law in all courts of justice" gives the lawyers of Indiana an opportunity to raise the standards of the profession free from the limitations of this unwise restriction. It will not be necessary to change the legislative program of the association by reason of the decision, and the three bills approved by the association have been introduced as follows: H. B. 142, Procedural Bill restoring rule making power to Supreme Court H. B. 141, Judicial Council Bill H. B. 128, Integrated Bar Bill The usual opposition has developed, but the endorsement by all three of the Indianapolis newspapers as well as by many others in the State, the ap- proval of the bills in the Governor's message to the General Assembly and his explanation and endorsement of them over the radio, and friendly gestures from other sources have greatly encouraged the Legislative Committee. -

Research Guide

Research Guide FINDING CASES I. HOW TO FIND A CASE WHEN YOU KNOW THE CITATION A. DECIPHERING LEGAL CITATIONS 1. CASE CITATIONS A case citation includes: the names of the parties, the volume number of the case reporter, the abbreviated name of the reporter, the page number where the case can be found, and the year of the decision. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800 (1982). Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta = names of the parties 30 = volume number of the case reporter Cal. = abbreviated name of the case reporter, California Reports 3d = series number of the case reporter, California Reports 800 = page number of the case reporter (1982) = year of the decision 2. ABBREVIATIONS OF REPORTER NAMES The abbreviations used in citations can be deciphered by consulting: a. Prince’s Bieber Dictionary of Legal Abbreviations, 6th ed. (Ref. KF 246 .p74 2009) b. Black's Law Dictionary (Ref. KF 156 .B624 2009). This legal dictionary contains a table of abbreviations. Copies of Black's are located on dictionary stands throughout the library, as well as in the Reference Collection. 3. REPORTERS AND PARALLEL CITATIONS A case may be published in more than one reporter. Parallel citations indicate the different reporters publishing the same case. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800, 180 Cal. Rptr. 628, 640 P.2d 764 (1982). 02/08/12 (Rev.) RG14 (OVER) This case will be found in three places: the "official" California Reports 3d (30 Cal. 3rd 800); and the two "unofficial" West reporters: the California Reporter (180 Cal. -

Handbook on Briefs and Oral Arguments

HANDBOOK ON BRIEFS AND ORAL ARGUMENTS by THE HON. ROBERT E. DAVISON and DAVID P. BERGSCHNEIDER ©2007 by the Office of the State Appellate Defender. All rights reserved. Updated 2020 by: Kerry Bryson & Shawn O’Toole, Deputy State Appellate Defenders State Appellate Defender Offices Administrative Office Third District Office 400 West Monroe - Suite 202 770 E. Etna Road Springfield, Illinois 62705 Ottawa, Illinois 61350 Phone: (217) 782-7203 Phone: (815) 434-5531 Fax: (217) 782-5385 Fax: (815) 434-2920 First District Office Fourth District Office 203 N. LaSalle, 24th Floor 400 West Monroe - Suite 303 Chicago, Illinois 60601 Springfield, Illinois 62705-5240 Phone: (312) 814-5472 Phone: (217) 782-3654 Fax: (312) 814-1447 Fax: (217) 524-2472 Second District Office Fifth District Office One Douglas Avenue, 2nd Floor 909 Water Tower Circle Elgin, Illinois 60120 Mount Vernon, Illinois 62864 Phone: (847) 695-8822 Phone: (618) 244-3466 Fax: (847) 695-8959 Fax: (618) 244-8471 Juvenile Defender Resource Center 400 West Monroe, Suite 202 Springfield, Illinois 62704 Phone: (217) 558-4606 Email: [email protected] i INTRODUCTION The first edition of this Handbook was written in the early 1970's by Kenneth L. Gillis, who went on to become a Circuit Court Judge in Cook County. The Handbook was later expanded by Robert E. Davison, former First Assistant Appellate Defender and Circuit Court Judge in Christian County. Although the Handbook has been updated on several occasions, the contributions of Judges Gillis and Davison remain an essential part. The lawyers who use this Handbook are encouraged to offer suggestions for improving future editions. -

WRITING MANUAL a Guide to Citations, Style, and Judicial Opinion Writing

T S C of O WRITING MANUAL A Guide to Citations, Style, and Judicial Opinion Writing effective july 1, 2013 second edition Published for the Supreme Court of Ohio WRITING MANUAL A Guide to Citations, Style, and Judicial Opinion Writing MAUREEN O’CONNOR Chief Justice SHARON L. KENNEDY JUDITH L. FRENCH PATRICK F. FISCHER R. PATRICK DeWINE MICHAEL P. DONNELLY MELODY J. STEWART Justices The Supreme Court of Ohio Style Manual Committee HON. JUDITH ANN LANZINGER JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO Chair HON. TERRENCE O’DONNELL JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO HON. JUDITH L. FRENCH JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO STEVEN C. HOLLON ADMINISTRATIVE DIRECTOR, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO ARTHUR J. MARZIALE JR., Retired July 31, 2012 DIRECTOR OF LEGAL RESOURCES, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO SANDRA H. GROSKO REPORTER OF DECISIONS, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO RALPH W. PRESTON, Retired July 31, 2011 REPORTER OF DECISIONS, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO MARY BETH BEAZLEY ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF LAW AND DIRECTOR OF LEGAL WRITING, MORITZ COLLEGE OF LAW, THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY C. MICHAEL WALSH ADMINISTRATOR, NINTH APPELLATE DISTRICT The committee wishes to gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contributions of editor Pam Wynsen of the Reporter’s Office, as well as the excellent formatting assistance of John VanNorman, Policy and Research Counsel to the Administrative Director. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...........................................................................................................................ix PART I. MANUAL OF CITATIONS INTRODUCTION TO THE MANUAL OF CITATIONS .................................................3 SECTION ONE: CASES ....................................................................................................5 1.1. Ohio Court Cases .........................................................................................5 A. Importance of May 1, 2002 .................................................................5 B. Ohio cases decided before May 1, 2002 .............................................5 C. -

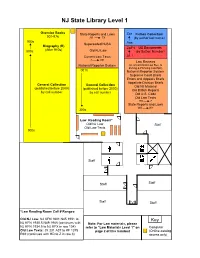

NJ State Library Level 1

NJ State Library Level 1 Oversize Books State Reports and Laws Zzz Fiction Collection 001-976 AK TX (by author last name) 900s Superseded NJSA Aaa Biography (B) Zp/P4 US Documents (After 910s) 800s Old NJ Law (by SuDoc Number) Current Law Texts A1.1 A KE Law Reviews National Reporter System (U. of Cincinnati Law Rev. to Zoning & Planning Law Rpt.) 001s National Reporter System Supreme Court Briefs Errors and Appeals Briefs Appellate Division Briefs General Collection General Collection Old NJ Material (published before 2000) (published before 2000) Old British Reports by call number by call number Old U.S. Code Old Law Texts HD Z State Reports and Laws WA WY 300s Law Reading Room* Old NJ Law Staff Old Law Texts 300s Staff Staff Staff Staff Staff *Law Reading Room Call # Ranges: Old NJ Law: NJ KFN 1801 N45 1981 to Key NJ KFN 1930.5 N49 1988 (continues with Note: For Law materials, please NJ KFN 1934.5 to NJ KFX in row 104) refer to “Law Materials Level 1” on Computer Old Law Texts: JX 231 A37 to KF 1375 page 2 of this handout (Online-catalog R69 (continues with HD to Z in row 3) access only) Law Materials Level 1 Title Row Title Row Alabama Reports and Session Laws 107 NJ Forms Legal and Business 11 Alaska Reports and Session Laws 107 NJ Law Journal 119 Alcoholic Beverage Control 12 NJ Law Reports 10 American Digest 99 NJ Law Times Reporter 10 American Jurisprudence 99 NJ Laws 11 Arizona Reports and Session Laws 107 NJ Legislative Index 11 Arkansas Reports and Session Laws 107, 108 NJ Misc. -

Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law Peter W

Cornell Law Library Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship Spring 2011 Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law Peter W. Martin Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Courts Commons, Legal Writing and Research Commons, and the Science and Technology Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Peter W., "Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law" (2011). Cornell Law Faculty Publications. Paper 1197. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/1197 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE JOURNAL OF APPELLATE PRACTICE AND PROCESS ARTICLES ABANDONING LAW REPORTS FOR OFFICIAL DIGITAL CASE LAW* Peter W. Martin** I. INTRODUCTION Like most states Arkansas entered the twentieth century with the responsibility for case law publication imposed by law on a public official lodged within the judicial branch. The "reporter's" office was then, as it is still today, a "constitutional" one.' Title and role reach all the way back to Arkansas's * Q Peter W. Martin, 2011. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 543 Howard Street, 5th Floor, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. -

Supreme Court of Ohio Writing Manual Is the First Comprehensive Guide to Judicial Opinion Writing Published by the Court for Its Use

T S C of O WRITING MANUAL A Guide to Citations, Style, and Judicial Opinion Writing effective july 1, 2013 second edition Published for the Supreme Court of Ohio WRITING MANUAL A Guide to Citations, Style, and Judicial Opinion Writing MAUREEN O’CONNOR Chief Justice SHARON L. KENNEDY PATRICK F. FISCHER R. PATRICK DeWINE MICHAEL P. DONNELLY MELODY J. STEWART JENNIFER BRUNNER Justices STEPHANIE E. HESS Interim administrative Director The Supreme Court of Ohio Style Manual Committee HON. JUDITH ANN LANZINGER JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO Chair HON. TERRENCE O’DONNELL JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO HON. JUDITH L. FRENCH JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO STEVEN C. HOLLON ADMINISTRATIVE DIRECTOR, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO ARTHUR J. MARZIALE JR., Retired July 31, 2012 DIRECTOR OF LEGAL RESOURCES, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO SANDRA H. GROSKO REPORTER OF DECISIONS, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO RALPH W. PRESTON, Retired July 31, 2011 REPORTER OF DECISIONS, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO MARY BETH BEAZLEY ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF LAW AND DIRECTOR OF LEGAL WRITING, MORITZ COLLEGE OF LAW, THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY C. MICHAEL WALSH ADMINISTRATOR, NINTH APPELLATE DISTRICT The committee wishes to gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contributions of editor Pam Wynsen of the Reporter’s Office, as well as the excellent formatting assistance of John VanNorman, Policy and Research Counsel to the Administrative Director. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...........................................................................................................................ix -

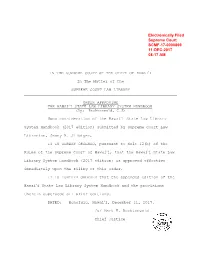

Hawaiʻi State Law Library System Handbook

Electronically Filed Supreme Court SCMF-17-0000869 11-DEC-2017 08:17 AM IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF HAWAI#I In The Matter of the SUPREME COURT LAW LIBRARY ORDER APPROVING THE HAWAI#I STATE LAW LIBRARY SYSTEM HANDBOOK (By: Recktenwald, C.J) Upon consideration of the Hawai#i State Law Library System Handbook (2017 edition) submitted by Supreme Court Law Librarian, Jenny R. Silbiger, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED, pursuant to Rule 12(b) of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Hawai#i, that the Hawai#i State Law Library System Handbook (2017 edition) is approved effective immediately upon the filing of this order. IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the appended edition of the Hawai#i State Law Library System Handbook and the provisions therein supersede all prior editions. DATED: Honolulu, Hawai#i, December 11, 2017. /s/ Mark E. Recktenwald Chief Justice Hawai‘i State Law Library System Handbook Revised September 2017 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Locations and Contact Information …………………………………………………….……………... 2 Security ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Library Hours ……………………………………………………………………………………….…… 3 Accommodations for Patrons with Disabilities ………………………………………………….…… 3 Collections …………………………………………………………………………………………….… 3 Online Public Access Catalog (OPAC) ………………………………………………………….…… 3 Borrowing Privileges ………………………………………………………………………………….... 4 Reference Services …………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Electronic Resources …………………………………………………………………………………... 4 Public Computers …………………………………………………………………………………....... -

How to Locate a Case Using a Digest

Sacramento County Public Law Library 609 9th St. Sacramento, CA 95814 saclaw.org (916) 874-6012 >> Home >> Law 101 DIGESTS How to Locate a Case Using a Digest The Law Library has two sets of West Digests in print format (now published by Thomson Reuters): Table of Contents The United States Supreme Court Digest, used to locate 1. How to Locate a Case Using United States Supreme Court cases, is located in Compact Topic and Key Number System in Shelving next to the Supreme Court Reporter, at KF 101 .1 Westlaw ...................................... 2 U55. Like all digests, each volume in the set is updated 2. Abbreviations and Locations of with pocket parts. Case Reporters ............................ 4 West’s California Digest, located in Row C-9 of Compact Shelving at KFC 57 .W47, is used to locate California Supreme Court and California Appellate Court cases. Digests are arranged alphabetically by topic. Examples of the approximately 400 topics are: Banks and Banking, Franchises, Insurance, Libel and Slander, Partnership, Fraud, and Criminal Law. Each topic is divided into subtopics known as "key numbers." A complete list of topic headings is available in the front of each digest volume. A complete list of key numbers is available at the beginning of each topic. A Quick Reference Guide to West Key Number System is available online west.thomson.com/documentation/westlaw/wlawdoc/wlres/keynmb06.pdf. Locate a topic and key number that interests you by scanning the list of topic headings and key numbers or by using the Descriptive Word Index at the end of each set of digests. -

William Taylor Muse Law Library University of Richmond School of Law

William Taylor Muse Law Library University of Richmond School of Law Research Guide : Federal Case Law Introduction Case law is the law as evidenced by a written judicial opinion. It is distinguished from statutory or administrative law although it frequently interprets these types of law. A judicial opinion is the expressed reasoning for the conclusion in a certain case. This research guide discusses how to locate federal case law. Although the focus here is on federal cases, the principles utilized to locate federal case law are applicable for locating the case law of a particular state. Basics Publication of opinions — Judicial opinions are published in three stages. The first is in the form of a slip opinion issued and published by the court soon after the decision is handed down. The second stage of publication is known as advance sheets, a portion of opinions that are ultimately published in the same reporter volume. Advance sheets typically contain the volume and page numbers of the future reporter volume. The final stage of publication is the actual reporter volume. The reporter contains several advance sheets bound into a new volume of the respective reporter series. Published v. Unpublished opinions — Not all cases result in judicial opinions that are published. Published opinions are available both online and in hard copy in one of the various series of reporters. — With regard to the federal courts of appeals, only those opinions deemed to have ―general precedential value‖ are designated for publication by the court. As of January 1, 2001, some unpublished opinions of the federal courts of appeals can be located in the Federal Appendix. -

Loislaw Case Coverage Federal Reporters

Loislaw Case Coverage Loislaw includes comprehensive coverage of cases and associated citations for the reporters and date ranges listed here (except as noted for the F. Supp and B.R. reporters) and select coverage of cases and associated citations for unofficial reporters not listed here or reporters outside of the date ranges we cover. Jurisdiction Court Reporter Citation Style Date Range Volumes Status Federal Reporters U.S. U.S. Supreme Court U.S. Reports U.S. 1754-present 1-present Official Supreme Court Reporter S.Ct. 1935-present 55-present Unofficial U.S. 1st Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F 3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F 2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 7th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S.