Case Reporter Copyright and the Universal Citation System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West V. Mead Data Central: Has Copyright Protection Been Stretched Too Far Thomas P

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 10 | Number 1 Article 4 1-1-1987 West v. Mead Data Central: Has Copyright Protection Been Stretched Too Far Thomas P. Higgins Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Thomas P. Higgins, West v. Mead Data Central: Has Copyright Protection Been Stretched Too Far, 10 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 95 (1987). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol10/iss1/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. West v. Mead Data Central: Has Copyright Protection Been Stretched Too Far? by THOMAS P. HIGGINS* Introduction Users of Lexis1 will not find pinpoint cites2 to page numbers in West's reporters. In a decision that has raised some eye- brows in the legal community,3 the Eighth Circuit held that Mead Data Central's (MDC) case retrieval system, LEXIS, probably infringes on the copyright of West Publishing's case reporters by including West's page numbers in its database.4 The decision raises important questions about the extent of copyright protection. For example, the Arabic number system is not copyrightable,5 and neither are judicial opinions.6 How- * A.B., Vassar College; Member, Third Year class. -

01-618. Eldred V. Ashcroft

1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES 2 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -X 3 ERIC ELDRED, ET AL., : 4 Petitioners : 5 v. : No. 01-618 6 JOHN D. ASHCROFT, ATTORNEY : 7 GENERAL : 8 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -X 9 Washington, D.C. 10 Wednesday, October 9, 2002 11 The above-entitled matter came on for oral 12 argument before the Supreme Court of the United States at 13 10:03 a.m. 14 APPEARANCES: 15 LAWRENCE LESSIG, ESQ., Stanford, California; on behalf of 16 the Petitioners. 17 THEODORE B. OLSON, ESQ., Solicitor General, Department of 18 Justice, Washington, D.C.; on behalf of the 19 Respondent. 20 21 22 23 24 25 1 Alderson Reporting Company 1111 14th Street, N.W. Suite 400 1-800-FOR-DEPO Washington, DC 20005 1 C O N T E N T S 2 ORAL ARGUMENT OF PAGE 3 LAWRENCE LESSIG, ESQ. 4 On behalf of the Petitioners 3 5 ORAL ARGUMENT OF 6 THEODORE B. OLSON, ESQ. 7 On behalf of the Respondent 25 8 REBUTTAL ARGUMENT OF 9 LAWRENCE LESSIG, ESQ. 10 On behalf of the Petitioners 48 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 2 Alderson Reporting Company 1111 14th Street, N.W. Suite 400 1-800-FOR-DEPO Washington, DC 20005 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 (10:03 a.m.) 3 CHIEF JUSTICE REHNQUIST: We'll hear argument 4 now in Number 01-618, Eric Eldred v. John D. Ashcroft. 5 Mr. Lessig. 6 ORAL ARGUMENT OF LAWRENCE LESSIG 7 ON BEHALF OF THE PETITIONERS 8 MR. -

Exploring the Application of Copyright Law to Library Catalog Records, 4 Computer L.J

The John Marshall Journal of Information Technology & Privacy Law Volume 4 Issue 2 Computer/Law Journal - Fall 1983 Article 3 Fall 1983 Ownership of Access Information: Exploring the Application of Copyright Law to Library Catalog Records, 4 Computer L.J. 305 (1983) Celia Delano Moore Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/jitpl Part of the Computer Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Legal Writing and Research Commons, Privacy Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Celia Delano Moore, Ownership of Access Information: Exploring the Application of Copyright Law to Library Catalog Records, 4 Computer L.J. 305 (1983) https://repository.law.uic.edu/jitpl/vol4/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The John Marshall Journal of Information Technology & Privacy Law by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OWNERSHIP OF ACCESS INFORMATION: EXPLORING THE APPLICATION OF COPYRIGHT LAW TO LIBRARY CATALOG RECORDS by CELIA DELANO MOORE* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................ 306 II. TRADITIONAL CATALOGING AND COPYRIGHT LAW. 307 A. COPYRIGHT IN THE CATALOG RECORD ................... 307 1. Nature of the Catalog Record ....................... 307 a. Descriptive Cataloging........................... 308 b. Subject Cataloging............................... 310 2. Subject Matter of Copyright ......................... 311 a. Fixation .......................................... 312 b. Authorship ....................................... 312 c. Originality........................................ 312 3. The Catalog Record As the Subject of Copyright ... 314 B. COPYRIGHT IN THE LIRARY CATALOG ................... 315 1. Nature of the Library Catalog ..................... -

Illustrators' Partnership of America and Co-Chair of the American Society of Illustrators Partnership, Is One of Those Opponents

I L L U S T R A T O R S ‘ P A R T N E R S H I P 8 4 5 M O R A I N E S T R E E T M A R S H F I E L D , M A S S A C H U S E T T S USA 0 2 0 5 0 t 7 8 1 - 8 3 7 - 9 1 5 2 w w w . i l l u s t r a t o r s p a r t n e r s h i p . o r g February 3, 2013 Maria Pallante Register of Copyrights US Copyright Office 101 Independence Ave. S.E. Washington, D.C. 20559-6000 RE: Notice of Inquiry, Copyright Office, Library of Congress Orphan Works and Mass Digitization (77 FR 64555) Comments of the Illustrators’ Partnership of America In its October 22, 2012 Notice of Inquiry, the Copyright Office has asked for comments from interested parties regarding “what has changed in the legal and business environments during the past four years that might be relevant to a resolution of the [orphan works] problem and what additional legislative, regulatory, or voluntary solutions deserve deliberation at this time.” As rightsholders, we welcome and appreciate the opportunity to comment. In the past, we have not opposed orphan works legislation in principle; but we have opposed legislation drafted so broadly that it would have permitted the widespread orphaning and infringement of copyright-protected art. In 2008, the Illustrators’ Partnership was joined by 84 other creators’ organizations in opposing that legislation; 167,000 letters were sent to members of Congress from our website. -

A Handbook of Citation Form for Law Clerks at the Appellate Courts of the State of Hawai#I

A HANDBOOK OF CITATION FORM FOR LAW CLERKS AT THE APPELLATE COURTS OF THE STATE OF HAWAI ###I 2008 Edition Hawai #i State Judiciary 417 South King Street Honolulu, HI 96813 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. CASES............................................ .................... 2 A. Basic Citation Forms ............................................... 2 1. Hawai ###i Courts ............................................. 2 a. HAWAI #I SUPREME COURT ............................... 2 i. Pre-statehood cases .............................. 2 ii. Official Hawai #i Reports (volumes 1-75) ............. 3 iii. West Publishing Company Volumes (after 75 Haw.) . 3 b. INTERMEDIATE COURT OF APPEALS ........................ 3 i. Official Hawai #i Appellate Reports (volumes 1-10) . 3 ii. West Publishing Company Volumes (after 10 Haw. App.) .............................................. 3 2. Federal Courts ............................................. 4 a. UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT ......................... 4 b. UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS ...................... 4 c. DISTRICT COURTS ...................................... 4 3. Other State Courts .......................................... 4 B. Case Names ................................................... 4 1. Case Names in Textual Sentences .............................. 5 a. ACTIONS AND PARTIES CITED ............................ 5 b. PROCEDURAL PHRASES ................................. 5 c. ABBREVIATIONS ....................................... 5 i. in textual sentences .............................. 5 ii. business -

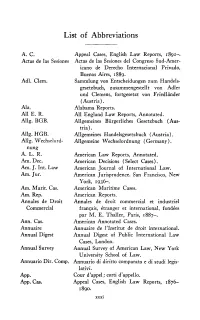

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations A. C. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, r8gr-. Aetas de las Sesiones Aetas de las Sesiones del Congreso Sud-Amer icano de Derecho Internacional Privado, Buenos Aires, r88g. Adl. Clem. Sammlung von Entscheidungen zum Handels gesetzbuch, zusammengestellt von Adler und Clemens, fortgesetzt von Friedlander (Austria). Ala. Alabama Reports. All E. R. All England Law Reports, Annotated. Allg. BGB. Allgemeines Biirgerliches Gesetzbuch (Aus- tria). Allg. HGB. Allgemeines Handelsgesetzbuch (Austria). All g. W echselord- Allgemeine Wechselordnung (Germany). nung A. L. R. American Law Reports, Annotated. Am. Dec. American Decisions ( Select Cases) . Am. J. Int. Law American Journal of International Law. Am. Jur. American Jurisprudence. San Francisco, New York, 1936-. Am. Marit. Cas. American Maritime Cases. Am. Rep. American Reports. Annales de Droit Annales de droit commercial et industriel Commercial fran~ais, etranger et international, fondees par M. E. Thaller, Paris, r887-. Ann. Cas. American Annotated Cases. Annuaire Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international. Annual Digest Annual Digest of Public International Law Cases, London. Annual Survey Annual Survey of American Law, New York University School of Law. Annuario Dir. Camp. Annuario di diritto comparato e di studi legis lativi. App. Cour d'appel; corti d'appello. App. Cas. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, 1876- r8go. xxxi XXXll LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS App. D.C. Appeal Cases, District of Columbia. App. Div. New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division Reports. Arch. Civ. Prax. Archiv fiir die civilistische Praxis (Germany) . Arch. Jud. Archivo judiciario (Brazil). Ariz. Arizona Reports. Ark. Arkansas Reports. Asp. Marit. Cas. Aspinall's Maritime Cases. Atl. Atlantic Reporter, National Reporter System (United States). -

ELDRED V. ASHCROFT: the CONSTITUTIONALITY of the COPYRIGHT TERM EXTENSION ACT by Michaeljones

COPYRIGHT ELDRED V. ASHCROFT: THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE COPYRIGHT TERM EXTENSION ACT By MichaelJones On January 15, 2003, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Copyright Term Extension Act ("CTEA"), which extended the term of copyright protection by twenty years.2 The decision has been ap- plauded by copyright protectionists who regard the extension as an effec- tive incentive to creators. In their view, it is a perfectly rational piece of legislation that reflects Congress's judgment as to the proper copyright term, balances the interests of copyright holders and users, and brings the3 United States into line with the European Union's copyright regime. However, the CTEA has been deplored by champions of a robust public domain, who see the extension as a giveaway to powerful conglomerates, which runs contrary to the public interest.4 Such activists see the CTEA as, in the words of Justice Stevens, a "gratuitous transfer of wealth" that will impoverish the public domain. 5 Consequently, Eldred, for those in agree- ment with Justice Stevens, is nothing less than the "Dred Scott case for 6 culture." The Court in Eldred rejected the petitioners' claims that (1) the CTEA did not pass constitutional muster under the Copyright Clause's "limited © 2004 Berkeley Technology Law Journal & Berkeley Center for Law and Technology. 1. Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, 17 U.S.C. §§ 108, 203, 301-304 (2002). The Act's four provisions consider term extensions, transfer rights, a new in- fringement exception, and the division of fees, respectively; this Note deals only with the first provision, that of term extensions. -

13-485 Comptroller of Treasury of MD. V. Wynne (05/18/2015)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2014 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus COMPTROLLER OF THE TREASURY OF MARYLAND v. WYNNE ET UX. CERTIORARI TO THE COURT OF APPEALS OF MARYLAND No. 13–485. Argued November 12, 2014—Decided May 18, 2015 Maryland’s personal income tax on state residents consists of a “state” income tax, Md. Tax-Gen. Code Ann. §10–105(a), and a “county” in- come tax, §§10–103, 10–106. Residents who pay income tax to anoth- er jurisdiction for income earned in that other jurisdiction are al- lowed a credit against the “state” tax but not the “county” tax. §10– 703. Nonresidents who earn income from sources within Maryland must pay the “state” income tax, §§10–105(d), 10–210, and nonresi- dents not subject to the county tax must pay a “special nonresident tax” in lieu of the “county” tax, §10–106.1. Respondents, Maryland residents, earned pass-through income from a Subchapter S corporation that earned income in several States. Respondents claimed an income tax credit on their 2006 Maryland income tax return for taxes paid to other States. The Mary- land State Comptroller of the Treasury, petitioner here, allowed re- spondents a credit against their “state” income tax but not against their “county” income tax and assessed a tax deficiency. -

The Copyright Act of 1976 (As Amended and Codified)

The Copyright Act of 1976 (as amended and codified) The Act of October 19, 1976 , Public Law Number 94-553 , 90 Stat. 2598, effective January 1, 1978. Chronology of Amendments Public Law No. 95-94 , 91 Stat. 653, 682 (Aug. 5, 1977) amended Sections 203 and 708. Public Law No. 95-598 , 92 Stat. 2676 (Nov. 6, 1978) amended Section 201. Public Law No. 96-517 , 94 Stat. 3028 (Dec. 12, 1980) amended Sections 101 and 117. Public Law No. 97-180 , 96 Stat. 93 (May 24, 1982) amended Section 506. Public Law No. 97-215 , 96 Stat. 178 (July 13, 1982) amended Section 601. Public Law No. 97-366 , 96 Stat. 1759 (Oct. 25, 1982) amended Section 110, 708. Public Law No. 98-450 , 98 Stat. 1727 (Oct. 4, 1984) amended Sections 109 and 115. Public Law No. 98-620 , 98 Stat. 3347 (Nov. 8, 1984) added Chapter 9 (§ § 901 et seq. ). Public Law No. 99-397 , 100 Stat. 848 (Aug. 27, 1986) amended Sections 111 and 801. Public Law No. 100-159 , 101 Stat. 900 (Nov. 9, 1987) amended Sections 902 and 914. Public Law No. 100-568 , 102 Stat. 2853 (Oct. 31, 1988) added Section 116A and amended Sections 101, 116, 205, 301, 401, 402, 403, 404, 405, 406, 407, 408, 411, 501, 504, 801, and 804. Public Law No. 100-617 , 102 Stat. 3194 (Nov. 5, 1988) amended Section 109 and 17 U.S.C. § 109 note. Public Law No. 100-667 , 102 Stat. 3949 (Nov. 16, 1988) added Section 119 and amended Sections 111, 501, 801, and 804. -

An Unconventional Approach to Reviewing the Judicially Unreviewable: Applying the Dormant Commerce Clause to Copyright Donald P

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 104 | Issue 1 Article 5 2016 An Unconventional Approach to Reviewing the Judicially Unreviewable: Applying the Dormant Commerce Clause to Copyright Donald P. Harris Temple University Beasley School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Harris, Donald P. (2016) "An Unconventional Approach to Reviewing the Judicially Unreviewable: Applying the Dormant Commerce Clause to Copyright," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 104 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol104/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Unconventional Approach to Reviewing the Judicially Unreviewable: Applying the Dormant Commerce Clause to Copyright Donald P. Harris' "[B]y virtually ignoring the central purpose of the Copyright/Patent Clause ... the Court has quitclaimed to Congress its principal responsibility in this area of the law. Fairly read, the Court has stated that Congress' actions under the Copyright/Patent Clause are, for all intents and purposes, 2 judicially unreviewable." INTRODUCTION On July 15, 2014, the House Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet, held one of a number of hearings reviewing the Copyright Act.3 This particular hearing focused, among other things, on the copyright term (the length over which copyrights are protected).4 While it is not surprising that Congress is again considering the appropriate term for copyrights- Congress has reviewed and increased the copyright term many times since the first Copyright Act of 1791 5-it is troubling because Congress has unfettered discretion in doing so. -

Principles of Administrative Law 1

CP Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD PRINCIPLES OF LAW SERIES Professor Paul Dobson Visiting Professor at Anglia Polytechnic University Professor Nigel Gravells Professor of English Law, Nottingham University Professor Phillip Kenny Professor and Head of the Law School, Northumbria University Professor Richard Kidner Professor and Head of the Law Department, University of Wales, Aberystwyth In order to ensure that the material presented by each title maintains the necessary balance between thoroughness in content and accessibility in arrangement, each title in the series has been read and approved by an independent specialist under the aegis of the Editorial Board. The Editorial Board oversees the development of the series as a whole, ensuring a conformity in all these vital aspects. David Stott, LLB, LLM Deputy Head, Anglia Law School Anglia Polytechnic University Alexandra Felix, LLB, LLM Lecturer in Law, Anglia Law School Anglia Polytechnic University CP Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney First published in Great Britain 1997 by Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX. Telephone: 0171-278 8000 Facsimile: 0171-278 8080 e-mail: [email protected] Visit our Home Page on http://www.cavendishpublishing.com © Stott, D and Felix, A 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 9HE, UK, without the permission in writing of the publisher. -

Congress's Power to Promote the Progress of Science: Eldred V. Ashcroft

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2002 Congress's Power to Promote the Progress of Science: Eldred v. Ashcroft Lawrence B. Solum Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/879 http://ssrn.com/abstract=337182 36 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 1-82 (2002) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons CONGRESS'S POWER TO PROMOTE THE PROGRESS OF SCIENCE: ELDRED V. ASHCROFT* Lawrence B. Solum** I. INTRODUCTION: ELDRED V. ASHCROFT ................................... 3 A. The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act ................. 4 B. ProceduralHistory ............................................................ 7 II. A TEXTUAL AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE COPYRIGHT C LA U SE .......................................................................................... 10 A. The Structure of the Clause .................................................... 11 1. The parallel construction of the copyright and patent powers in the Intellectual Property Clause .................... 11 2. The structure of the Copyright Clause ........................... 12 * © 2002 by the Author. Permission is hereby granted to duplicate this Essay for classroom use and for the inclusion of excerpts of any length in edu- cational materials of any kind, so long as the author and original publication is clearly identified and this notice is included. Permission for other uses may be obtained from the Author. ** Visiting Professor of Law, University of San Diego School of Law and Professor of Law and William M. Rains Fellow, Loyola Law School, Loyola Marymount University.