INTRODUCTION to the GUIANESE POPULAR MUSICS Apollinaire Anakesa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean

Peter Manuel 1 / Introduction Contradance and Quadrille Culture in the Caribbean region as linguistically, ethnically, and culturally diverse as the Carib- bean has never lent itself to being epitomized by a single music or dance A genre, be it rumba or reggae. Nevertheless, in the nineteenth century a set of contradance and quadrille variants flourished so extensively throughout the Caribbean Basin that they enjoyed a kind of predominance, as a common cultural medium through which melodies, rhythms, dance figures, and per- formers all circulated, both between islands and between social groups within a given island. Hence, if the latter twentieth century in the region came to be the age of Afro-Caribbean popular music and dance, the nineteenth century can in many respects be characterized as the era of the contradance and qua- drille. Further, the quadrille retains much vigor in the Caribbean, and many aspects of modern Latin popular dance and music can be traced ultimately to the Cuban contradanza and Puerto Rican danza. Caribbean scholars, recognizing the importance of the contradance and quadrille complex, have produced several erudite studies of some of these genres, especially as flourishing in the Spanish Caribbean. However, these have tended to be narrowly focused in scope, and, even taken collectively, they fail to provide the panregional perspective that is so clearly needed even to comprehend a single genre in its broader context. Further, most of these pub- lications are scattered in diverse obscure and ephemeral journals or consist of limited-edition books that are scarcely available in their country of origin, not to mention elsewhere.1 Some of the most outstanding studies of individual genres or regions display what might seem to be a surprising lack of familiar- ity with relevant publications produced elsewhere, due not to any incuriosity on the part of authors but to the poor dissemination of works within (as well as 2 Peter Manuel outside) the Caribbean. -

Légendes Et Crédits De L'iconographie Et Des Objets Exposés

Légendes et crédits de l’iconographie et des objets exposés 1 Salle 1 : entrée et accueil - Salle 2 Panneau Histoire d’une zone administrative autonome « Mission 1951 : Monpera, le chef des Indiens Emerillons qui a retrouvé les carnets de et la carabine de Raymond Maufrais salue le gendarme Chauveau » ; photographie parue dans la revue Gendarmerie nationale, n° 17, 3e trimestre, 1983, p. 14. © Droits réservés ; cliché repris par Gérard Thabouillot, Territoire de l’Inini (1930-1969), Matoury, Ibis Rouge Editions, 2016, p. 711. Panneau Des débuts sous le sceau du volontarisme [Le gouverneur Veber visite le village boni d’Apatou, lors d’une tournée sur le Maroni (1936)]. © Collection privée ; cliché publié par Gérard Thabouillot, Le Territoire de l’Inini (1930-1969), Matoury, Ibis Rouge Editions, 2016, p. 317. Panneau Une anomalie républicaine [Amérindien wayana conduisant à la pagaie une pirogue sur le Maroni ou l’un de ses affluents] ; photographie (1958-1960). © Collection privée. Panneau Le débat politique sur le statut de la Guyane Guyane française et territoire de l’Inini ; échelle 1/3 000 000. Carte extraite de La géologie et les mines de la France d’outre-mer, Paris, Société d’éditions géographiques, maritimes et coloniales (1932). © Collectivité Territoriale de Guyane-Bibliothèque Alexandre-Franconie. Numérisé par Manioc : permalien http://www.manioc.org/images/FRA120070020i1. 2 Salle 3 Boîtes - Echantillons de bois (vers 1938). Musée territorial Alexandre-Franconie, collection René Grébert, chef du service Eaux et Forêts de la Guyane française et du Territoire de l’Inini. - Céramique wayana avec décor de motifs géométriques sur la panse (fabrication contemporaine). -

Le Fidèle Apatou in the French Wilderness In: New West Indian Guide

K. Bilby The explorer as hero: Le Fidèle Apatou in the French wilderness In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 78 (2004), no: 3/4, Leiden, 197-227 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 06:30:31AM via free access KENNETH BlLBY THE EXPLORER AS HERO: LE FIDELE APATOU IN THE FRENCH WILDERNESS For a brief spell during the closing years of the nineteenth century, a South American Maroon named Apatu became the toast of France, at least that portion of the French public that thrilled to the pages of Le Tour du Monde, a popular adventure series that inspired the likes of Jules Verne.1 Hailing from the borderlands between French and Dutch Guiana, a part of the Amazon basin that was still only nominally under the control of the two competing European powers that had laid claim to the area, Apatu had joined forces with the French explorer Jules Crevaux. In doing so, he had caused alarm among his own people, the Aluku, who continued to regard whites with great suspicion. Over a period of several months, Crevaux and Apatu had penetrated rivers and forests that had yet to appear on European maps; by the time they arrived at the mouth of the Amazon River in Brazil, they had also cemented a friendship that was to bring them together for a number of other journeys over the next few years, a friendship that would last until Crevaux's death in 1882.2 By Crevaux's own account, Apatu had not only 1. -

In and out of Suriname Caribbean Series

In and Out of Suriname Caribbean Series Series Editors Rosemarijn Hoefte (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Gert Oostindie (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Editorial Board J. Michael Dash (New York University) Ada Ferrer (New York University) Richard Price (em. College of William & Mary) Kate Ramsey (University of Miami) VOLUME 34 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cs In and Out of Suriname Language, Mobility and Identity Edited by Eithne B. Carlin, Isabelle Léglise, Bettina Migge, and Paul B. Tjon Sie Fat LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 3.0) License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: On the road. Photo by Isabelle Léglise. This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface issn 0921-9781 isbn 978-90-04-28011-3 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-28012-0 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by the Editors and Authors. This work is published by Koninklijke Brill NV. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff and Hotei Publishing. Koninklijke Brill NV reserves the right to protect the publication against unauthorized use and to authorize dissemination by means of offprints, legitimate photocopies, microform editions, reprints, translations, and secondary information sources, such as abstracting and indexing services including databases. -

Jazz, Race, and Gender in Interwar Paris

1 CROSSING THE POND: JAZZ, RACE, AND GENDER IN INTERWAR PARIS A dissertation presented by Rachel Anne Gillett to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts May, 2010 2 CROSSING THE POND: JAZZ, RACE, AND GENDER IN INTERWAR PARIS by Rachel Anne Gillett Between 1920 and 1939 the nightclubs of Montmartre became a venue where different nationalities came into contact, danced, talked, and took advantage of the freedom to cross the color line that Paris and the ―color-blind‖ French audience seemed to offer. The fascination for black performers known as the tumulte noir provided the occasion for hundreds of jazz and blues performers to migrate to Paris in these years. French society was inundated with the sounds of jazz and also with images and stereotypes of jazz performers that often contained primitivist, exotic and sexualized associations. The popularity of jazz and its characterization as ―black‖ music raised the question of how the French state dealt with racial difference. It caused consternation among „non- jazz‟ black men and women throughout the Francophone Atlantic many of whom were engaged in constructing an intellectual pan-Africanist discourse with a view to achieving full citizenship and respect for French colonial subjects. This manuscript examines the tension between French ideals of equality, and „color-blindness,‟ and the actual experiences of black men and women in Paris between the wars. Although officially operating within the framework of a color-blind Republican model, France has faced acute dilemmas about how to deal with racial and ethnic differences that continue to spark debate and controversy. -

AATW-Latin-America-Song-By-Song

All Around This World Latin America Song-by-Song Overview African, European and Native American history may be present in every stroke of Latin music (and, even farther back, the North African/Roma-”gypsy”/Sephardic Jewish and other genres that influenced the music of Spain), but when the rhythms of sub-Saharan Africa fused with the Spanish melodies several hundred years ago, an entirely new and distinct set of “Afro-Latin” music formed. Today’s Latin music thrives on its own, inventing and reinventing itself. In Latin music, history may be everything, but the past is only a good indication of great music to come… 1) WE ARE HAPPY Country: Uganda (original)/ On CD:Dominican Republic Language: originally Luganda Genre on CD: Merengue Instruments on CD: Piano, Trombone, Trumpet We sing “We Are Happy” at the beginning of every All Around This World class, changing the hello to match the featured country of the week. All Around This World’s version is actually a mashup of two songs the Abayudaya of Uganda sing to greet important visitors to Nabugoye Hill, which is a small area a few miles outside of the Eastern Ugandan city of Mbale. The Abayudya of Uganda are a small community of about 500 Luganda-speaking Bagandans who have been practicing Judaism for over 80 years. Abayudaya community leaders Rabbi Gershom Sizomu and his brother JJ Keki wrote the two greeting songs and led the community in singing them for Jay when he first visited in late 1999. 2) LA GUACAMAYA Country: Mexico Language: Spanish Genre on CD: Son jarocho Instruments on CD: Jarana, Marimbula, Quijada, Requinto,Tarima “La Gucamaya” is a son jarocho song from Veracruz in Mexico. -

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

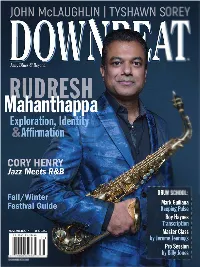

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

The Jamaican Marronage, a Social Pseudomorph: the Case of the Accompong Maroons

THE JAMAICAN MARRONAGE, A SOCIAL PSEUDOMORPH: THE CASE OF THE ACCOMPONG MAROONS by ALICE ELIZABETH BALDWIN-JONES Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2011 8 2011 Alice Elizabeth Baldwin-Jones All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THE JAMAICAN MARRONAGE, A SOCIAL PSEUDOMORPH: THE CASE OF THE ACCOMPONG MAROONS ALICE ELIZABETH BALDWIN-JONES Based on ethnography, oral history and archival research, this study examines the culture of the Accompong Maroons by focusing on the political, economic, social, religious and kinship institutions, foodways, and land history. This research demonstrates that like the South American Maroons, the Accompong Maroons differ in their ideology and symbolisms from the larger New World population. However, the Accompong Maroons have assimilated, accommodated and integrated into the state in every other aspect. As a consequence, the Accompong Maroons can only be considered maroons in name only. Today’s Accompong Maroons resemble any other rural peasant community in Jamaica. Grounded in historical analysis, the study also demonstrate that social stratification in Accompong Town results from unequal access to land and other resources, lack of economic infrastructure, and constraints on food marketeers and migration. This finding does not support the concept of communalism presented in previous studies. Table of Contents Page Part 1: Prologue I. Prologue 1 Theoretical Resources 10 Description of the Community 18 Methodology 25 Significance of the Study 30 Organization of the Dissertation 31 Part II: The Past and the Present II. The Political Structure – Past and Present 35 a. -

Jean-Philippe Fanfant Jean-Philippe Fanfant

Maq METHODE FANFANT kolory pop 14/12/07 13:22 Page 1 PREFACE La Caraïbe, de par son histoire, est le carrefour de plusieurs Caribbean music has many different influences, due to the his- influences : européennes, africaines et indiennes. Ce métissa- tory of the region. The interaction between the various euro- ge est l’essence même de la musique antillaise. pean, african & indian peoples is the very essence of Caribbean Chaque île, qu’elle soit anglophone, francophone ou hispa- music. nique, a vécu de manière différente les quatre derniers siècles Each island, be it English, French or Spanish speaking, has its et possède sa culture et ses rythmes propres. personal experience of the last four centuries and therefore has Le but de cette méthode est d'étudier leur adaptation à la bat- its own culture and particular rhythms. terie. The purpose of this book and CD is to study different possibili- La plupart des rythmes traditionnels correspondent à un chant ties of how to adapt these rhythms to the drumset. et une danse. Ils peuvent exprimer à la fois la révolte, l'espoir, Most of the traditional rhythms go with a song and dance. la gaîté ou la tristesse. En créole, on dit d’un rythme qu’il doit They can express rebellion, hope, joy or sorrow all at the same « roulé », ce qui veut dire « groover » donc être dansant. time. Dans l'interprétation de chaque exercice, il est nécessaire de In Creole, it is said that a rhythm should roll (“roulé” pronoun- sentir le mouvement. ced woo-ley ) or groove, and consequently you can dance to it! Parfois, les rythmes s'influencent les uns les autres et sont tou- Sometimes rhythms can be influenced by one another as they jours en évolution car la musique est vivante. -

Life After Zouk: Emerging Popular Music of the French Antilles

afiimédlsfiéi L x l 5 V. .26 l A 2&1“. 33.4“» ‘ firm; {a , -a- ‘5 .. ha.‘ .- A : a h ‘3‘ $1.". V ..\ n31... 3:..lx .La.tl.. A Zia. .. I: A 1 . 3‘ . 3x I. .01....2'515 A .{iii-3v. , am 3,. w Ed‘fim. ‘ 1’ A I .«LfiMA‘. 3 .u .. Al 1 : A 1. n- . ill. i. r . A P 2...: l. x .A .. .. e5? .ulc u «inn , . A . A » » . A V y k nu. z . at A. A .1? v I . UV}, — .. .7 , A A \.l .0 v- ’1 A .u‘. s A“. .4‘ I . 3...: 5 . V ruling I“. " o .33.): rt! .- Edit-{t . .V BAWAfiVxHF.‘ . .... .(._.r...|vuu\uut.fi . .! $43: This is to certify that the thesis entitled LIFE AFTER ZOUK: EMERGING POPULAR MUSIC OF THE FRENCH ANTILLES presented by Laura Caroline Donnelly has been accepted towards fulfillment of the requirements for the MA. degree in Musicology Ankh-7K ’4“ & Major Professor’s Signatye 17/6 / z m 0 Date MSU is an Affinnative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer LIBRARY Michigan State UI liversity PLACE IN RETURN BOX to remove this checkout from your record. TO AVOID FINES return on or before date due. MAY BE RECALLED with earlier due date if requested. DATE DUE DATE DUE DATE DUE 5/08 K:/Prolecc&Pres/ClRC/DateDue.indd LIFE AFTER ZOUK: EMERGING POPULAR MUSIC OF THE FRENCH ANTILLES By Laura Caroline Donnelly A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Musicology 2010 ABSTRACT LIFE AFTER ZOUK: EMERGING POPULAR MUSIC OF THE FRENCH ANTILLES By Laura Caroline Donnelly For the past thirty years, zouk has been the predominant popular music in the French Antilles. -

The Dichotomy of Universalism and Particularism in French Guiana Fred Réno, Bernard Phipps

The dichotomy of Universalism and Particularism in French Guiana Fred Réno, Bernard Phipps To cite this version: Fred Réno, Bernard Phipps. The dichotomy of Universalism and Particularism in French Guiana. Post colonial Trajectories in the Caribbean : the three Guianas, 2017. hal-02570348 HAL Id: hal-02570348 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570348 Submitted on 12 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The dichotomy of Universalism and Particularism in French Guiana Fred Réno and Bernard Phipps Post-Colonial Trajectories in the Caribbean The Three Guianas Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte, Matthew L. Bishop, Peter Clegg © 2017 – Routledge December 2015 was a landmark in the political history of French Guiana with the election of the new single territorial community – the collectivité unique - which enshrined the official demise of the Région and, more pertinently, the Département that had previously embodied the principle of assimilation of this South American French territory to France. Broadly-speaking, the traditional two-tier system – which exists all over metropolitan France, although, in contrast to those overseas, mainland Regions comprise multiple Departments – has been slimmed down and streamlined into a single political body combining the powers of the former two. -

Kalenda and Other Neo-African Dances in the Circum-Caribbean In

J. Gerstin Tangled roots: Kalenda and other neo-African dances in the circum-Caribbean In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 78 (2004), no: 1/2, Leiden, 5-41 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:58:55PM via free access JULIAN GERSTIN TANGLED ROOTS: KALENDA AND OTHER NEO-AFRICAN DANCES IN THE CIRCUM-CARIBBEAN In this article I investigate the early history of what John Storm Roberts (1972:26, 58) terms "neo-African" dance in the circum-Caribbean. There are several reasons for undertaking this task. First, historical material on early Caribbean dance and music is plentiful but scattered, sketchy, and contradic- tory. Previous collections have usually sorted historical descriptions by the names of dances; that is, all accounts of the widespread dance kalenda are treated together, as are other dances such as bamboula, djouba, and chica. The problem with this approach is that descriptions of "the same" dance can vary greatly. I propose a more analytical sorting by the details of descrip- tions, such as they can be gleaned. I focus on choreography, musical instru- ments, and certain instrumental practices. Based on this approach, I suggest some new twists to the historical picture. Second, Caribbean people today remain greatly interested in researching their roots. In large part, this article arises from my encounter, during eth- nographic work in Martinique, with local interpretations of one of the most famous Caribbean dances, kalenda.1 Martinicans today are familiar with at least three versions of kalenda: (1) from the island's North Atlantic coast, a virtuostic dance for successive soloists (usually male), who match wits with drummers in a form of "agonistic display" (Cyrille & Gerstin 2001; Barton 2002); (2) from the south, a dance for couples who circle one another slowly and gracefully; and (3) a fast and hypereroticized dance performed by tourist troupes, which invented it in the 1950s and 1960s.