Download (7Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Annual Report Pursuing Our Unlimited Potential Annual Report 2012

For the year ended March 31, 2012 Pursuing Our Unlimited Potential Annual Report 2012 Annual Report 2012 EAST JAPAN RAILWAY COMPANY JR East’s Strengths 1 AN OVERWHELMINGLY SOLID AND ADVANTAGEOUS RAILWAY NETWORK The railway business of the JR East Being based in the Tokyo metro- Group covers the eastern half of politan area is a major source of our Honshu island, which includes the strength. Routes originating in the Tokyo metropolitan area. We provide Kanto area (JR East Tokyo Branch transportation services via our Office, Yokohama Branch Office, Shinkansen network, which connects Hachioji Branch Office, Omiya Tokyo with regional cities in five Branch Office, Takasaki Branch directions, Kanto area network, and Office, Mito Branch Office, and intercity and regional networks. Our Chiba Branch Office) account for JR EAST’S SERVICE AREA networks combine to cover 7,512.6 68% of transportation revenue. kilometers and serve 17 million Japan’s total population may be people daily. We are the largest declining, but the population of the railway company in Japan and one of Tokyo metropolitan area (Tokyo, TOKYO the largest in the world. Kanagawa Prefecture, Saitama Prefecture, and Chiba On a daily basis, about 17million passengers travel a network of 70 train lines stretching 7,512.6 operating kilometers An Overwhelmingly Solid and Advantageous Railway Network Annual Report 2012 SECTION 1 OVERALL GROWTH STRATEGY Prefecture) continues to rise, mean- OPERATING REVENUES OPERATING INCOME ing our railway networks are sup- For the year ended March 31, 2012 For the year ended March 31, 2012 ported by an extremely sturdy Others 7.9% Transportation Others 6.1% Transportation operating foundation. -

Outdoor Club Japan (OCJ) 国際 アウトドア・クラブ・ジャパン Events

Outdoor Club Japan (OCJ) 国際 アウトドア・クラブ・ジャパン Events Norikuradake Super Downhill 10 March Friday to 12 March Monday If you are not satisfied ski & snowboard in ski area. You can skiing from summit. Norikuradake(3026m)is one of hundred best mountain in Japan. This time is good condition of backcountry ski season. Go up to the summit of Norikuradake by walk from the top of last lift(2000m). Climb about 5 hours and down to bottom lift(1500m) about 50 min. (Deta of last time) Transport: Train from Shinjuku to Matsumoto and Taxi from Matsumoto to Norikura-kogen. Return : Bus from Norikura-kogen to Sinshimashima and train to Shinjuku. Meeting Time & Place : 19:30 Shijuku st. platform 5 car no.1 for super Azusa15 Cost : About Yen30000 Train Shinjuku to matsumoto Yen6200(ow) but should buy 4coupon ticket each coupon Yen4190 or You can buy discount ticket shop in town price is similar. (price is non-reserve seat) Taxi about Yen13000 we will share. Return bus Yen1300 and local train Yen680. Inn Yen14000+tax 2 overnight 2 breakfast 1 dinner (no dinner Friday) Japanese room and hot spring! Necessary equipment : Skiers & Telemarkers need a nylon mohair skin. Snowboarders need snowshoes. Crampons(over 8point!) Clothes: Gore-tex jacket and pants, fleece, hut, musk, gloves, sunglasses, headlamp, thermos, lunch, sunscreen If you do not go up to the summit, you can enjoy the ski area and hot springs. 1 day lift pass Yen4000 Limit : 12persons (priority is downhill from summit) In Japanese : 026m)の頂上からの滑降です。 ゲレンデスキーに物足りないスキーヤー、スノーボーダー向き。 山スキーにいいシーズンですが、天気次第なので一応土、日と2日間の時間をとりました。 -

Symbol of Peace and Restoration Statue of “Kanaderu Otome” (A Girl Playing Guitar)

Community Information Paper Vol.33 December 2015 Issued by Azabu Regional City Office Edited by The Azabu Editing Office 5-16-45 Roppongi, Minato City, Tokyo 106-8515 Tel: 03-5114-8812 Fax: 03-3583-3782 Please contact Minato Call (City Information Service) for inquiries regarding Residents’ Life Support. Tel: 03-5472-3710 A community information paper created and edited by Azabu residents Fascinated by Artistic Azabu ⑦ Symbol of Peace and Restoration Statue of “Kanaderu Otome” (A Girl Playing Guitar) Shin Hongo (1905 – 1980) He was a leading sculptor of representational sculptures in Japan after the war, and a pio- neer of monumental statues and field sculp- tures. He was born and grew up in Sapporo. After graduating from the Craftworks and Sculpture Division, the Craft and Design De- partment of Koto Kogei Gakkou (tertiary insti- tution for crafts, presently the Department of Technology in Chiba University) in 1928, he studied under the great sculptor Kotaro Taka- mura. His representative works include a sculpture of a group of students who died in the war called “Kike Wadatsumi no Koe” (1950), the sculpture “Arashi no naka no Boshizo” (Mother and Child in a Storm) (1953), and more. (Pictures provided by Hongo Shin Memorial Museum of Sculpture, Sapporo) The coffee shop “Almond”, a famous都営地下鉄大江戸線 meeting 麻布十番駅 spot on a corner of the Roppongi Cross- ing, opened in 1964. Since 1954, 10 years before Almond was established, a statue of a 麻布十番大通り girl playing guitar has stood at the side of the crossing.東 京 メ トImmediately ロ 南 北 線 after the war, this Bronze Statue “Kanaderu Otome” by Shin Hongo statue, called “Kanaderu Otome,”きみちゃん像 was sculpted by Shin Hongo as a symbol of peace パ テ ィ オ 通 り パティオ and restoration. -

List of Certified Facilities (Cooking)

List of certified facilities (Cooking) Prefectures Name of Facility Category Municipalities name Location name Kasumigaseki restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Tokyo-club Building,3-2-6,Kasumigaseki,Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Sakura terrace,Iidabashi Grand Bloom,2-10- ALOHA TABLE iidabashi restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 2,Fujimi,Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku banquet kitchen The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 24th floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Peter The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Boutique & Café First basement, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Hei Fung Terrace The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Lobby 1-1-1,Uchisaiwai-cho,Chiyoda-ku TORAYA Imperial Hotel Store restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (Imperial Hotel of Tokyo,Main Building,Basement floor) mihashi First basement, First Avenu Tokyo Station,1-9-1 marunouchi, restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (First Avenu Tokyo Station Store) Chiyoda-ku PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Hot hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku Kitchen,Cold Kitchen) PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Preparation) hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku LE PORC DE VERSAILLES restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First~3rd floor, Florence Kudan, 1-2-7, Kudankita, Chiyoda-ku Kudanshita 8th floor, Yodobashi Akiba Building, 1-1, Kanda-hanaoka-cho, Grand Breton Café -

Ishikawa Access Map Kanazawa City Center

Golf Courses KANAZAWA CITY CENTER MAP A great number of scenic golf courses exist in Ishikawa, taking advantage of the many magnificent natural landscapes. Imagine golfing on top of a hill in Noto with shots seemingly descending down to the Sea of Japan, or at the foot of Mt. Hakusan where golfers dauntlessly shoot towars the massive mountainous background. Ishikawa of- 15 16 fers you a unique opportunity to not just play golf, but be one with nature as well! HEGURAJIMA Island The Country Club Noto Kanazawa Links Golf Club ❶● ⓭● 17 14 0768-52-3131 076-237-2222 http://www.cc-noto.co.jp/ Hotel Kanazawa ⓮● Kanazawa 6 ❷● Notojima Golf and Central Country Club 18 Asanogawa Country Club 076-251-0011 River Wajima 0767-85-2311 Kanazawa Kobo-Nagaya Senmaida Rice http://www.notojima-golf.jp/ ● Hakusan Country Club Hyakuban-gai 0761-51-4181 Shopping Mall Terrece http://www.incl.ne.jp/golf/haku/haku1.html ❸● Tokinodai Country Club 13 Suzuyaki Museum 0767-27-1121 4 of Art http://www.tokinodai.co.jp/ ● Kaga Huyo Country Club Wajima 0761-65-2020 2 12 Onsen ❹● Wakura Golf Club 3 0767-52-2580 ● Twin Fields Golf Club 2 Suzu 0761-47-4500 7 Mitsuke-jima http://www.wakuragolfclub.co.jp/ 1 5 Onsen http://www.twin-fields.com/ Hotel Nikko 19 Island ❺● Noto Golf Club Ishikawa Wajima Urushi 0767-32-1212 ● Komatsu Country Club ANA Crowne Plaza Hotel Museum of Art http://www.daiwaresort.co.jp/noto-gc/ 0761-43-3030 5 NANATSUJIMA ❻● Chirihama Country Club ● Komatsu Public Golf Course Island 0767-28-4411 0761-65-2277 10 ❼● Noto Country Club ● Kaga Country Club 0767-28-3155 -

Yamanaka Onsen Niigata Fukushima

Tourist map of Yamanaka Onsen Niigata Fukushima and Hokuriku area Nagaoka Joetsumyoko Sta. Itoigawa Echigoyuzawa Sta. Shintakaoka Sta. Iiyama Kurobe Kanazawa Unazukionsen Sta. Nagano Toyama Tateyama/Kurobe Kaga Onsen Sta. Komatsu Annakaharuna Sta. Utsunomiya Kenrokuen Garden Ueda Tojinbo Takasaki Awaraonsen Sta. Shirakawago Sakudaira Sta. Karuizawa Fukui Yamanaka Onsen Omiya The aroma of the Onsen has been healing travelers Nanjo Eiheiji Temple Tokyo since its inauguration 1300 years ago. Tsuruga Maibara Tottori Nagoya Kyoto Shizuoka Kobe Okayama Shinosaka Sta. Access to Yamanaka Onsen Train To JR Line Kaga Onsen Station ◎ Tokyo – Hokuriku Shinkansen (Kagayaki or Hakutaka) – Kanazawa – Hokuriku line express (Shirasagi or underbird) – Kaga Onsen station Approx 2 hours 55 minutes ◎ Tokyo – Tokaido Shinkansen (Hikari) – Maibara – Hokuriku line express (Shirasagi) – Kaga Onsen station Approx 3 hours 50 minutes ◎ Kyoto – Hokuriku line express (underbird) – Kaga Onsen station Approx 1 hour 45 minutes ◎ Osaka – Hokuriku line express (underbird) – Kaga Onsen station Approx 2 hours 20 minutes ◎ Nagoya – Tokaido Shinkansen (Hikari) – Maibara – Hokuriku line express (Shirasagi) – Kaga Onsen station Approx 2 hours 10 minutes ◎ Kanazawa – Hokuriku line express (Shirasagi or underbird) – Kaga Onsen station Approx 25 minutes * Time calculated for the fastest trains available. * Transportation services available from Kaga Onsen Station. * 20 minutes from Kaga Onsen Station by taxi. Hokuriku Shinkansen running between Kanazawa and Tokyo was put into service on March 14th 2015. Hokuriku Shinkansen made it 1 hour and 20 minutes faster to travel from Tokyo to Kanazawa. Airplane To Komatsu airport ◎ From Haneda Approx 1 hour ◎ From Narita Approx 1 hour 20 minutes ◎ From Sapporo Approx 1 hour 45 minutes ◎ From Sendai Approx 1 hour 10 minutes ◎ From Fukuoka Approx 1 hour 30 minutes * Approx 30 minutes by Can Bus from Komatsu airport to Kaga Onsen. -

Former House of the Ishimaru Family “L'assemblee HIROO”

Community Information Paper No.42 February 2018 Translated/Issued by Azabu Regional City Office Edited by the Azabu Editing Office 5-16-45 Roppongi, Minato City, Tokyo, 106-8515 Tel: 03-5114-8812 (Rep.) Fax: 03-3583-3782 Please contact Minato Call for inquiries regarding Residents’ Life Support. Tel: 03-5472-3710 A community information paper created and edited by people who live in Azabu. Fascinated by Artistic Azabu ⑮ A Mansion Preserved and Protected in the Azabu Area Former House of the Ishimaru Family “l’Assemblee HIROO” l’Assemblee HIROO Area of the premises: 542.1m2 (About 167.3 tsubo), Building floor space: 314.8m2 (About 97.2 tsubo) Do you know about this mansion quietly nestled along the Teppo-zaka alleyway slope in Minami Azabu? It turned 95 years old in 2017, but still has all the fascinating and elegant appearance it had when it was first built. This luxurious mansion was built for the late Mr. Sukezaburo In what was formerly a bedroom, there are several elements Ishimaru, upon his return from London in 1922. In the fol- of Japanese style, including sliding doors and tokonoma (al- lowing year, 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake struck this cove). However, all of this is matched harmoniously with the area. Fortunately, this building was not seriously damaged. Western-style fireplace, also designed in consideration of the family’s lifestyle. On the premises, there are three of the zelkova trees that are over 300 years old. There is a story that relates how, during The stone pillar in the dining room, the handrail of the stairs, the Great Tokyo Air Raid in 1945, those living in the neigh- and the beams in the student room on the top floor remain borhood poured water over this cypress tree to protect the unchanged and fully functional, the same as they have always Some earthquake reinforcement has been carried out for the building, and the stones forming the pillar are the same as tree. -

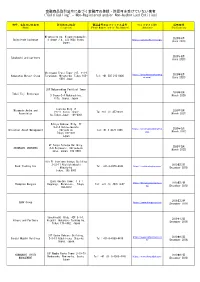

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered And/Or Non-Authorized Entities)

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered and/or Non-Authorized Entities) 商号、名称又は氏名等 所在地又は住所 電話番号又はファックス番号 ウェブサイトURL 掲載時期 (Name) (Location) (Phone Number and/or Fax Number) (Website) (Publication) Miyakojima-ku, Higashinodamachi, 2020年6月 SwissTrade Exchange 4-chōme−7−4, 534-0024 Osaka, https://swisstrade.exchange/ (June 2020) Japan 2020年6月 Takahashi and partners (June 2020) Shiroyama Trust Tower 21F, 4-3-1 https://www.hamamatsumerg 2020年6月 Hamamatsu Merger Group Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105- Tel: +81 505 213 0406 er.com/ (June 2020) 0001 Japan 28F Nakanoshima Festival Tower W. 2020年3月 Tokai Fuji Brokerage 3 Chome-2-4 Nakanoshima. (March 2020) Kita. Osaka. Japan Toshida Bldg 7F Miyamoto Asuka and 2020年3月 1-6-11 Ginza, Chuo- Tel:+81 (3) 45720321 Associates (March 2021) ku,Tokyo,Japan. 104-0061 Hibiya Kokusai Bldg, 7F 2-2-3 Uchisaiwaicho https://universalassetmgmt.c 2020年3月 Universal Asset Management Chiyoda-ku Tel:+81 3 4578 1998 om/ (March 2022) Tokyo 100-0011 Japan 9F Tokyu Yotsuya Building, 2020年3月 SHINBASHI VENTURES 6-6 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku (March 2023) Tokyo, Japan, 102-0083 9th Fl Onarimon Odakyu Building 3-23-11 Nishishinbashi 2019年12月 Rock Trading Inc Tel: +81-3-4579-0344 https://rocktradinginc.com/ Minato-ku (December 2019) Tokyo, 105-0003 Izumi Garden Tower, 1-6-1 https://thompsonmergers.co 2019年12月 Thompson Mergers Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Tel: +81 (3) 4578 0657 m/ (December 2019) 106-6012 2019年12月 SBAV Group https://www.sbavgroup.com (December 2019) Sunshine60 Bldg. 42F 3-1-1, 2019年12月 Hikaro and Partners Higashi-ikebukuro Toshima-ku, (December 2019) Tokyo 170-6042, Japan 31F Osaka Kokusai Building, https://www.smhpartners.co 2019年12月 Sendai Mubuki Holdings 2-3-13 Azuchi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tel: +81-6-4560-4410 m/ (December 2019) Osaka, Japan. -

Supporting Daily Lives, Enabling Brighter Futures

●Kamei (Corporate Sales Division) ●Pacific Co., Ltd. Our Mission ●Kamei (Residential Division) ●Shiogama Petroleum Disaster Prevention Co., Ltd. Supporting daily lives, ●Kamei (Carlife Division) ●Tochigi LPG Co., Ltd. ●Kamei Physical Distribution Services Co., Ltd. ●Sennan Energy Co., Ltd. ●Fuji Oil Service, Co., Ltd. ●Shinshirakawa LPG Supply Center Co., Ltd. Creating new value as enabling brighter futures ●Noshiro Daiichi Kyubin Co., Ltd. ●Saito Gas Co., Ltd. Since our establishment in 1903 in Shiogama, Miyagi, Japan, ●Tohoku Gas Corporation we face a changing Kamei Corporation has evolved as a community-based company society in a new era. that provides products and services which are essential to Energy people`s daily lives. This fundamental management principle persists even though we have now developed into a global corporation. As a “people`s company” which supports and ●Kamei (Residential Division) By combining daily perseverance with our improves people`s daily lives, we will continue to contribute to the Broadcasting Housing ●Kamei (Construction Materials Division) customer-oriented philosophy, Kamei has development of society. ●Kamei Engineering Co., Ltd. been able to contribute to the development of local industries and people`s daily lives. ●Miyagi Television Broadcasting Co., Ltd. ●Kamei (Food Division) Currently, society is in a major transitional ●Miyagi Television Service Co., Ltd. ●Higuchi Beikoku Co., Ltd. period, and as such, it is becoming necessary to resolve new issues such as the ●Ikemitsu Enterprises Co., Ltd. globalization of the economy and the ●Wing Ace Corporation conservation of the global environment. ●Vintners Inc. Agri Corporation ● The needs of society are also becoming ●Oshimaonoshoji Co., Ltd. Pet Food ●Sun-Eight Trading Co., Ltd. -

Shinkansen Bullet Train

Jōetsu Shinkansen (333.9 km) Train Names: TOKI, TANIGAWA Max-TOKI, Max-TANIGAWA JAPAN RAIL PASS Can also be Used for Shinkansen Jōetsu Shinkansen "Max-TOKI"etc. “bullet train” Travel Akita Shinkansen "KOMACHI" Akita Shinkansen (662.6 km) Train Name: KOMACHI Akita Shin-Aomori Yamagata Shinkansen "TSUBASA" Hokuriku Shinkansen (450.5 km) Yamagata Shinkansen Train Names: KAGAYAKI, HAKUTAKA, (421.4 km) Shinjo¯ Morioka TSURUGI, ASAMA Train Name: TSUBASA Niigata Yamagata Sendai Kanazawa Toyama Nagano Hokuriku Shinkansen "KAGAYAKI"etc. Fukushima Takasaki Omiya¯ Sanyō & Kyūshū Shinkansen "SAKURA" Sanyō Shinkansen (622.3 km) Train Names: NOZOMI*, MIZUHO*, Tōhoku Shinkansen "HAYABUSA "etc. Tōkaidō & Sanyō Shinkansen "HIKARI" HIKARI (incl. HIKARI Rail Star), SAKURA, KODAMA Tōkaidō Shinkansen (552.6 km) (Tōkyō thru Hakata, 1,174.9km) Train Names: NOZOMI*, HIKARI, KODAMA Hakata Kokura Hiroshima Okayama Shin-Osaka¯ Kyōto Nagoya Shin-Yokohama Shinagawa Tokyo¯ ¯ * There are six types of train services, “NOZOMI,” “MIZUHO,” “HIKARI,” “SAKURA,” “KODAMA” and “TSUBAME” trains on the Tōkaidō, Sanyō and Kyūshū Shinkansen, and the stations at which trains stop vary with train types. The JAPAN RAIL PASS is only valid for “HIKARI,” “SAKURA,” “KODAMA” Tōhoku Shinkansen "HAYATE," "YAMABIKO,"etc. and “TSUBAME” trains, and not valid for any seats, reserved or non-reserved, on “NOZOMI” and “MIZUHO” trains. To travel on the Tōkaidō, Sanyō and Kyūshū Shinkansen, the pass holders must take Tōhoku Shinkansen (713.7 km) “HIKARI,” “SAKURA,” “KODAMA” or “TSUBAME” trains, or -

Saitama Prefecture Kanagawa Prefecture Tokyo Bay Chiba

Nariki-Gawa Notake-Gawa Kurosawa-Gawa Denu-Gawa Nippara-Gawa Kitaosoki-Gawa Saitama Prefecture Yanase-Gawa Shinshiba-Gawa Gake-Gawa Ohba-Gawa Tama-Gawa Yana-Gawa Kasumi-Gawa Negabu-Gawa Kenaga-Gawa Hanahata-Gawa Mizumotokoaitame Tamanouchi-Gawa Tobisu-Gawa Shingashi-Gawa Kitaokuno-Gawa Kita-Gawa Onita-Gawa Kurome-Gawa Ara-Kawa Ayase-Gawa Chiba Prefecture Lake Okutama Narahashi-Gawa Shirako-Gawa Shakujii-Gawa Edo-Gawa Yozawa-Gawa Koi-Kawa Hisawa-Gawa Sumida-Gawa Naka-Gawa Kosuge-Gawa Nakano-Sawa Hirai-Gawa Karabori-Gawa Ochiai-Gawa Ekoda-Gawa Myoushoji-Gawa KItaaki-Kawa Kanda-Gawa Shin-Naka-Gawa Zanbori-Gawa Sen-Kawa Zenpukuji-Gawa Kawaguchi-Gawa Yaji-Gawa Tama-Gawa Koto Yamairi-Gawa Kanda-Gawa Aki-Kawa No-Gawa Nihonbashi-Gawa Inner River Ozu-Gawa Shin-Kawa Daigo-Gawa Ne-Gawa Shibuya-Gawa Kamejima-Gawa Osawa-Gawa Iruma-Gawa Furu-Kawa Kyu-Edo-Gawa Asa-Kawa Shiroyama-Gawa Asa-Gawa Nagatoro-Gawa Kitazawa-Gawa Tsukiji-Gawa Goreiya-Gawa Yamada-Gawa Karasuyama-Gawa Shiodome-Gawa Hodokubo-Gawa Misawa-Gawa Diversion Channel Minami-Asa-Gawa Omaruyato-Gawa Yazawa-Gawa Jukuzure-Gawa Meguro-Gawa Yudono-Gawa Oguri-Gawa Hyoe-Gawa Kotta-Gawa Misawa-Gawa Annai-Gawa Kuhonbutsu-Gawa Tachiai-Gawa Ota-Gawa Shinkoji-Gawa Maruko-Gawa Sakai-Gawa Uchi-Kawa Tokyo Bay Tsurumi-Gawa Aso-Gawa Nomi-Kawa Onda-Gawa Legend Class 1 river Ebitori-Gawa Managed by the minister of land, Kanagawa Prefecture infrastructure, transport and tourism Class 2 river Tama-Gawa Boundary between the ward area and Tama area Secondary river. -

What Is the JR East Group Doing to Prevent Global Warming?

Environmental Environmental Measures to Prevent Global Warming What is the JR East Group Doing to Prevent Global Warming? In an effort to reduce its CO2 emission levels, the JR East Group promotes greater energy efficiency and the use of renewable energy. It also is promoting intermodal transportation, aimed at reducing CO2 emissions of the country's entire transportation system. Transportation volume (billion car-km) Energy flows of JR East Reducing energy consumption in Trend in energy consumption for train Measures to Prevent operations versus transportation volume Energy consumption for train operations (billion MJ) Energy consumption per unit of transportation train operations volume (MJ/car-km) Global Warming (Billion car-km) (Billion MJ) (MJ/car-km) Inputs/Outputs Electricity sources Energy consumption By the end of fiscal 2004, JR East had 9,410 2.2 50 20.6 (4%reduction) 21 (10%reduction) 19.7 (9%reduction) (11%reduction) (13%reduction) Energy supply and consumption energy-saving railcars in operation. This 18.8 17.9 City gas, kerosene, 18.6 18.3 JR East thermal plant Conventional railway lines (15%reduction) The energy consumed by JR East consists of elec- class C heavy oil amounts to 76% of the entire railcar fleet. 17.5 2.44 billion kWh 39% 3.11 billion kWh 50% Electricity trical and non-electrical power. Electrical power Shinkansen lines We are steadily replacing railcars on conven- 1.29 million t-CO2 *2 2.1 25 15 6.19 44.0 comes from electrical utility companies and JR 1.10 billion kWh 8% tional lines with energy-saving railcars equipped 43.1 JR East hydropower plants billion kWh 41.0 40.6 40.5 39.3 Stations, offices, etc.