First Law of Thermodynamics: Control Volumes Here We Will Extend the Conservation of Energy to Systems That Involve Mass Flow Across Their Boundaries, Control Volumes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

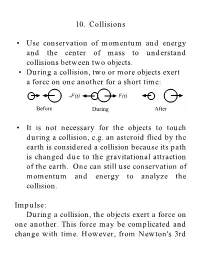

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, Heat, and Entropy

3.012 Fundamentals of Materials Science Fall 2005 Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, heat, and entropy Today: LAST TIME .........................................................................................................................................................................................2� State functions ..............................................................................................................................................................................2� Path dependent variables: heat and work..................................................................................................................................2� DEFINING TEMPERATURE ...................................................................................................................................................................4� The zeroth law of thermodynamics .............................................................................................................................................4� The absolute temperature scale ..................................................................................................................................................5� CONSEQUENCES OF THE RELATION BETWEEN TEMPERATURE, HEAT, AND ENTROPY: HEAT CAPACITY .......................................6� The difference between heat and temperature ...........................................................................................................................6� Defining heat capacity.................................................................................................................................................................6� -

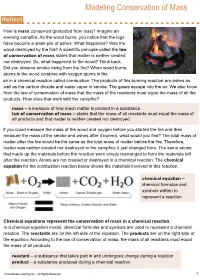

Modeling Conservation of Mass

Modeling Conservation of Mass How is mass conserved (protected from loss)? Imagine an evening campfire. As the wood burns, you notice that the logs have become a small pile of ashes. What happened? Was the wood destroyed by the fire? A scientific principle called the law of conservation of mass states that matter is neither created nor destroyed. So, what happened to the wood? Think back. Did you observe smoke rising from the fire? When wood burns, atoms in the wood combine with oxygen atoms in the air in a chemical reaction called combustion. The products of this burning reaction are ashes as well as the carbon dioxide and water vapor in smoke. The gases escape into the air. We also know from the law of conservation of mass that the mass of the reactants must equal the mass of all the products. How does that work with the campfire? mass – a measure of how much matter is present in a substance law of conservation of mass – states that the mass of all reactants must equal the mass of all products and that matter is neither created nor destroyed If you could measure the mass of the wood and oxygen before you started the fire and then measure the mass of the smoke and ashes after it burned, what would you find? The total mass of matter after the fire would be the same as the total mass of matter before the fire. Therefore, matter was neither created nor destroyed in the campfire; it just changed form. The same atoms that made up the materials before the reaction were simply rearranged to form the materials left after the reaction. -

Linear-Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics Theory for Coupled Heat and Mass Transport

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Chemical and Biomolecular Research Papers -- Yasar Demirel Publications Faculty Authors Series 2001 Linear-nonequilibrium thermodynamics theory for coupled heat and mass transport Yasar Demirel University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Stanley I. Sandler University of Delaware, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cbmedemirel Part of the Chemical Engineering Commons Demirel, Yasar and Sandler, Stanley I., "Linear-nonequilibrium thermodynamics theory for coupled heat and mass transport" (2001). Yasar Demirel Publications. 8. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cbmedemirel/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Chemical and Biomolecular Research Papers -- Faculty Authors Series at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yasar Demirel Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 44 (2001), pp. 2439–2451 Copyright © 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. Used by permission. www.elsevier.comllocate/ijhmt Submitted November 5, 1999; revised September 6, 2000. Linear-nonequilibrium thermodynamics theory for coupled heat and mass transport Yasar Demirel and S. I. Sandler Center for Molecular and Engineering Thermodynamics, Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716, USA Corresponding author — Y. Demirel Abstract Linear-nonequilibrium thermodynamics (LNET) has been used to express the entropy generation and dis- sipation functions representing the true forces and flows for heat and mass transport in a multicomponent fluid. These forces and flows are introduced into the phenomenological equations to formulate the cou- pling phenomenon between heat and mass flows. -

Law of Conversation of Energy

Law of Conservation of Mass: "In any kind of physical or chemical process, mass is neither created nor destroyed - the mass before the process equals the mass after the process." - the total mass of the system does not change, the total mass of the products of a chemical reaction is always the same as the total mass of the original materials. "Physics for scientists and engineers," 4th edition, Vol.1, Raymond A. Serway, Saunders College Publishing, 1996. Ex. 1) When wood burns, mass seems to disappear because some of the products of reaction are gases; if the mass of the original wood is added to the mass of the oxygen that combined with it and if the mass of the resulting ash is added to the mass o the gaseous products, the two sums will turn out exactly equal. 2) Iron increases in weight on rusting because it combines with gases from the air, and the increase in weight is exactly equal to the weight of gas consumed. Out of thousands of reactions that have been tested with accurate chemical balances, no deviation from the law has ever been found. Law of Conversation of Energy: The total energy of a closed system is constant. Matter is neither created nor destroyed – total mass of reactants equals total mass of products You can calculate the change of temp by simply understanding that energy and the mass is conserved - it means that we added the two heat quantities together we can calculate the change of temperature by using the law or measure change of temp and show the conservation of energy E1 + E2 = E3 -> E(universe) = E(System) + E(Surroundings) M1 + M2 = M3 Is T1 + T2 = unknown (No, no law of conservation of temperature, so we have to use the concept of conservation of energy) Total amount of thermal energy in beaker of water in absolute terms as opposed to differential terms (reference point is 0 degrees Kelvin) Knowns: M1, M2, T1, T2 (Kelvin) When add the two together, want to know what T3 and M3 are going to be. -

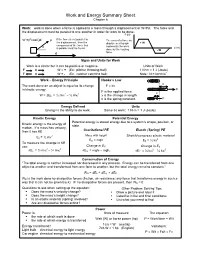

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Key Concepts: Conservation of Mass, Momentum, Energy Fluid: a Material

Key concepts: Conservation of mass, momentum, energy Fluid: a material that deforms continuously and permanently under the application of a shearing stress, no matter how small. Fluids are either gases or liquids. (Under very specialized conditions, a phase of intermediate properties can be stable, but we won’t consider that possibility.) In liquids, the molecules are relatively closely spaced, allowing the magnitude of their (attractive, electrically-based) interaction energy to be of the same magnitude as their kinetic energy. As a result, they exist as a loose collection of clusters. In gases, the molecules are much more widely separated, so the kinetic energy (at a given temperature, identical to that in the liquid) is far greater than the interaction energy (much less than in the liquid), and molecule do not form clusters. In a liquid, the molecules themselves typically occupy a few percent of the total space available; in a gas, they occupy a few thousandths of a percent. Nevertheless, for our purposes, all fluids are considered to be continua (no voids or holes).The absence of significant intermolecular attraction allows gases to fill whatever volume is available to them, whereas the presence of such attraction in liquids prevents them from doing so. The attractive forces in liquid water are unusually strong, compared to other liquids. Properties of Fluids: m Density is mass/volume: ρ = . The density of liquid water is V 3 o −3 3 ~1.0 kg/m ; that of air at 20 C is ~1.2x10 kg/m . mg W Specific weight is weight/volume: γ = = = ρg V V C:\Adata\CLASNOTE\342\Class Notes\Key concepts_Topic 1.doc 1 γ Specific gravity is density normalized to the density of water: sg..= i γ w V 1 Specific volume is volume/mass: V = = m ρ Bulk modulus or modulus of elasticity is the pressure change per dp dp fractional change in volume or density: E =− = . -

Damage Cases and Environmental Releases from Mines and Mineral Processing Sites

DAMAGE CASES AND ENVIRONMENTAL RELEASES FROM MINES AND MINERAL PROCESSING SITES 1997 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Solid Waste 401 M Street, SW Washington, DC 20460 Contents Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Discussion and Summary of Environmental Releases and Damages ......................... Page 1 Methodology for Developing Environmental Release Cases ............................... Page 19 ARIZONA ASARCO Silver Bell Mine: "Waste and Process Water Discharges Contaminate Three Washes and Ground Water" ................................................... Page 24 Cyprus Bagdad Mine: "Acidic, Copper-Bearing Solution Seeps to Boulder Creek" ................................ Page 27 Cyprus Twin Buttes Mine: "Tank Leaks Acidic Metal Solution Resulting in Possible Soil and Ground Water Contamination" ...................................... Page 29 Magma Copper Mine: "Broken Pipeline Seam Causes Discharge to Pinal Creek" ................................ Page 31 Magma Copper Mine: "Multiple Discharges of Polluted Effluents Released to Pinto Creek and Its Tributaries" .................................................... Page 33 Magma Copper Mine: "Multiple Overflows Result in Major Fish Kill in Pinto Creek" ............................... Page 36 Magma Copper Mine: "Repeated Release of Tailings to Pinto Creek" .......................................... Page 39 Phelps Dodge Morenci Mine: "Contaminated Storm Water Seeps to Ground Water and Surface Water" ................................................................ Page 43 Phelps Dodge -

Chapter 3 3.4-2 the Compressibility Factor Equation of State

Chapter 3 3.4-2 The Compressibility Factor Equation of State The dimensionless compressibility factor, Z, for a gaseous species is defined as the ratio pv Z = (3.4-1) RT If the gas behaves ideally Z = 1. The extent to which Z differs from 1 is a measure of the extent to which the gas is behaving nonideally. The compressibility can be determined from experimental data where Z is plotted versus a dimensionless reduced pressure pR and reduced temperature TR, defined as pR = p/pc and TR = T/Tc In these expressions, pc and Tc denote the critical pressure and temperature, respectively. A generalized compressibility chart of the form Z = f(pR, TR) is shown in Figure 3.4-1 for 10 different gases. The solid lines represent the best curves fitted to the data. Figure 3.4-1 Generalized compressibility chart for various gases10. It can be seen from Figure 3.4-1 that the value of Z tends to unity for all temperatures as pressure approach zero and Z also approaches unity for all pressure at very high temperature. If the p, v, and T data are available in table format or computer software then you should not use the generalized compressibility chart to evaluate p, v, and T since using Z is just another approximation to the real data. 10 Moran, M. J. and Shapiro H. N., Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics, Wiley, 2008, pg. 112 3-19 Example 3.4-2 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A closed, rigid tank filled with water vapor, initially at 20 MPa, 520oC, is cooled until its temperature reaches 400oC. -

Pressure Vs. Volume and Boyle's

Pressure vs. Volume and Boyle’s Law SCIENTIFIC Boyle’s Law Introduction In 1642 Evangelista Torricelli, who had worked as an assistant to Galileo, conducted a famous experiment demonstrating that the weight of air would support a column of mercury about 30 inches high in an inverted tube. Torricelli’s experiment provided the first measurement of the invisible pressure of air. Robert Boyle, a “skeptical chemist” working in England, was inspired by Torricelli’s experiment to measure the pressure of air when it was compressed or expanded. The results of Boyle’s experiments were published in 1662 and became essentially the first gas law—a mathematical equation describing the relationship between the volume and pressure of air. What is Boyle’s law and how can it be demonstrated? Concepts • Gas properties • Pressure • Boyle’s law • Kinetic-molecular theory Background Open end Robert Boyle built a simple apparatus to measure the relationship between the pressure and volume of air. The apparatus ∆h ∆h = 29.9 in. Hg consisted of a J-shaped glass tube that was Sealed end 1 sealed at one end and open to the atmosphere V2 = /2V1 Trapped air (V1) at the other end. A sample of air was trapped in the sealed end by pouring mercury into Mercury the tube (see Figure 1). In the beginning of (Hg) the experiment, the height of the mercury Figure 1. Figure 2. column was equal in the two sides of the tube. The pressure of the air trapped in the sealed end was equal to that of the surrounding air and equivalent to 29.9 inches (760 mm) of mercury. -

Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, Thermodynamic Inequalities

Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, Thermodynamic Inequalities Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities A.G. Petukhov, PHYS 743 October 4, 2017 Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, ThermodynamicA.G. Petukhov,October Inequalities PHYS 4, 743 2017 1 / 12 Maximum Work If a thermally isolated system is in non-equilibrium state it may do work on some external bodies while equilibrium is being established. The total work done depends on the way leading to the equilibrium. Therefore the final state will also be different. In any event, since system is thermally isolated the work done by the system: jAj = E0 − E(S); where E0 is the initial energy and E(S) is final (equilibrium) one. Le us consider the case when Vinit = Vfinal but can change during the process. @ jAj @E = − = −Tfinal < 0 @S @S V The entropy cannot decrease. Then it means that the greater is the change of the entropy the smaller is work done by the system The maximum work done by the system corresponds to the reversible process when ∆S = Sfinal − Sinitial = 0 Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, ThermodynamicA.G. Petukhov,October Inequalities PHYS 4, 743 2017 2 / 12 Clausius Theorem dS 0 R > dS < 0 R S S TA > TA T > T B B A δQA > 0 B Q 0 δ B < The system following a closed path A: System receives heat from a hot reservoir. Temperature of the thermostat is slightly larger then the system temperature B: System dumps heat to a cold reservoir. Temperature of the system is slightly larger then that of the thermostat Chapter II. -

The Application of Temperature And/Or Pressure Correction Factors in Gas Measurement COMBINED BOYLE’S – CHARLES’ GAS LAWS

The Application of Temperature and/or Pressure Correction Factors in Gas Measurement COMBINED BOYLE’S – CHARLES’ GAS LAWS To convert measured volume at metered pressure and temperature to selling volume at agreed base P1 V1 P2 V2 pressure and temperature = T1 T2 Temperatures & Pressures vary at Meter Readings must be converted to Standard conditions for billing Application of Correction Factors for Pressure and/or Temperature Introduction: Most gas meters measure the volume of gas at existing line conditions of pressure and temperature. This volume is usually referred to as displaced volume or actual volume (VA). The value of the gas (i.e., heat content) is referred to in gas measurement as the standard volume (VS) or volume at standard conditions of pressure and temperature. Since gases are compressible fluids, a meter that is measuring gas at two (2) atmospheres will have twice the capacity that it would have if the gas is being measured at one (1) atmosphere. (Note: One atmosphere is the pressure exerted by the air around us. This value is normally 14.696 psi absolute pressure at sea level, or 29.92 inches of mercury.) This fact is referred to as Boyle’s Law which states, “Under constant tempera- ture conditions, the volume of gas is inversely proportional to the ratio of the change in absolute pressures”. This can be expressed mathematically as: * P1 V1 = P2 V2 or P1 = V2 P2 V1 Charles’ Law states that, “Under constant pressure conditions, the volume of gas is directly proportional to the ratio of the change in absolute temperature”. Or mathematically, * V1 = V2 or V1 T2 = V2 T1 T1 T2 Gas meters are normally rated in terms of displaced cubic feet per hour.