Forest As Volk: Ewiger Wald and the Religion of Nature in the Third Reich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collective Identity in Germany: an Assessment of National Theories

James Madison Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 7 | Issue 1 2019-2020 Collective Identity in Germany: An Assessment of National Theories Sean Starkweather James Madison University Follow this and other works at: http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/jmurj Recommended APA 7 Citation Starkweather, S. (2020). Collective identity in Germany: An assessment of national theories. James Madison Undergraduate Research Journal, 7(1), 36-48. http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/jmurj/vol7/iss1/4 This full issue is brought to you for free and open access by JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in James Madison Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Collective Identity in Germany An Assessment of National Theories Sean Starkweather “Köln stellt sich quer - Tanz die AfD” by Elke Witzig is licensed under CC BY-SA-4.0 Beginning in the 18th century, the question of what makes a nation has occupied a prominent place in German politics. From the national theories of the 18th-century German Romantics, who identified cultural and ethnic factors as being the key determinants, to modern civic nationalists and postnationalists, who point to liberal civic values and institutions, the importance of collective identity and how it is oriented has remained an important topic for German scholars and policymakers. Using survey research, I assess the accuracy and relevance of these theories in contemporary German society. I find that, contrary to the optimism of modern thinkers, German collective identity remains aligned with the national theories of the Romantics, resulting in ethnic discrimination and heightened fears over the loss of culture through external ideological and ethnic sources. -

![Autarky and Lebensraum. the Political Agenda of Academic Plant Breeding in Nazi Germany[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9515/autarky-and-lebensraum-the-political-agenda-of-academic-plant-breeding-in-nazi-germany-1-289515.webp)

Autarky and Lebensraum. the Political Agenda of Academic Plant Breeding in Nazi Germany[1]

Journal of History of Science and Technology | Vol.3 | Fall 2009 Autarky and Lebensraum. The political agenda of academic plant breeding in Nazi Germany[1] By Thomas Wieland * Introduction In a 1937 booklet entitled Die politischen Aufgaben der deutschen Pflanzenzüchtung (The Political Objectives of German Plant Breeding), academic plant breeder and director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (hereafter KWI) for Breeding Research in Müncheberg near Berlin Wilhelm Rudorf declared: “The task is to breed new crop varieties which guarantee the supply of food and the most important raw materials, fibers, oil, cellulose and so forth from German soils and within German climate regions. Moreover, plant breeding has the particular task of creating and improving crops that allow for a denser population of the whole Nordostraum and Ostraum [i.e., northeastern and eastern territories] as well as other border regions…”[2] This quote illustrates two important elements of National Socialist ideology: the concept of agricultural autarky and the concept of Lebensraum. The quest for agricultural autarky was a response to the hunger catastrophe of World War I that painfully demonstrated Germany’s dependence on agricultural imports and was considered to have significantly contributed to the German defeat in 1918. As Herbert Backe (1896–1947), who became state secretary in 1933 and shortly after de facto head of the German Ministry for Food and Agriculture, put it: “World War 1914–18 was not lost at the front-line but at home because the foodstuff industry of the Second Reich [i.e., the German Empire] had failed.”[3] The Nazi regime accordingly wanted to make sure that such a catastrophe would not reoccur in a next war. -

![Guide to the MS-196: “Meine Fahrten 1925-1938” Scrapbook [My Trips 1925-1938]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6096/guide-to-the-ms-196-meine-fahrten-1925-1938-scrapbook-my-trips-1925-1938-296096.webp)

Guide to the MS-196: “Meine Fahrten 1925-1938” Scrapbook [My Trips 1925-1938]

________________________________________________________________________ Guide to the MS-196: “Meine Fahrten 1925-1938” Scrapbook [My Trips 1925-1938] Jesse Siegel ’16, Smith Project Intern July 2016 MS – 196: “Meine Fahrten” Scrapbook (Title page, 36 pages) Inclusive Dates: October 1925—April 1938 Bulk Dates: 1927, 1929-1932 Processed by: Jesse Siegel ’16, Smith Project Intern July 15, 2016 Provenance Purchased from Between the Covers Company, 2014. Biographical Note Possibly a group of three brothers—G. Leiber, V. Erich Leiber, and R. Leiber— participated in the German youth movement during the 1920s and 1930s. The probable maker of the photo album, Erich Leiber, was probably born before 1915 in north- western Germany, most likely in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. His early experiences with the youth movement appear to have been in conjunction with school outings and Christian Union for Young Men (CVJM) in Austria. He also travelled to Sweden in 1928, but most of his travels are concentrated in northwestern Germany. Later in 1931 he became an active member in a conservative organization, possibly the Deutsche Pfadfinderschaft St. Georg,1 participating in outings to nationalistic locations such as the Hermann Monument in the Teutoburg Forest and to the Naval Academy at Mürwik in Kiel. In 1933 Erich Leiber joined the SA and became a youth leader or liaison for a Hitler Youth unit while still maintaining a connection to a group called Team Yorck, a probable extension of prior youth movement associates. After 1935 Erich’s travels seem reduced to a small group of male friends, ending with an Easter trip along the Rhine River in 1938. -

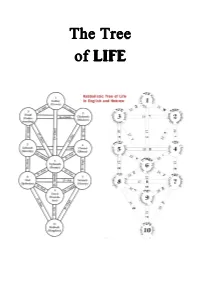

The Tree of LIFE

The Tree of LIFE ~ 2 ~ ~ 3 ~ ~ 4 ~ Trees of Life. From the highest antiquity trees were connected with the gods and mystical forces in nature. Every nation had its sacred tree, with its peculiar characteristics and attributes based on natural, and also occasionally on occult properties, as expounded in the esoteric teachings. Thus the peepul or Âshvattha of India, the abode of Pitris (elementals in fact) of a lower order, became the Bo-tree or ficus religiosa of the Buddhists the world over, since Gautama Buddha reached the highest knowledge and Nirvâna under such a tree. The ash tree, Yggdrasil, is the world-tree of the Norsemen or Scandinavians. The banyan tree is the symbol of spirit and matter, descending to the earth, striking root, and then re-ascending heavenward again. The triple- leaved palâsa is a symbol of the triple essence in the Universe - Spirit, Soul, Matter. The dark cypress was the world-tree of Mexico, and is now with the Christians and Mahomedans the emblem of death, of peace and rest. The fir was held sacred in Egypt, and its cone was carried in religious processions, though now it has almost disappeared from the land of the mummies; so also was the sycamore, the tamarisk, the palm and the vine. The sycamore was the Tree of Life in Egypt, and also in Assyria. It was sacred to Hathor at Heliopolis; and is now sacred in the same place to the Virgin Mary. Its juice was precious by virtue of its occult powers, as the Soma is with Brahmans, and Haoma with the Parsis. -

Depopulation: on the Logic of Heidegger's Volk

Research research in phenomenology 47 (2017) 297–330 in Phenomenology brill.com/rp Depopulation: On the Logic of Heidegger’s Volk Nicolai Krejberg Knudsen Aarhus University [email protected] Abstract This article provides a detailed analysis of the function of the notion of Volk in Martin Heidegger’s philosophy. At first glance, this term is an appeal to the revolutionary mass- es of the National Socialist revolution in a way that demarcates a distinction between the rootedness of the German People (capital “P”) and the rootlessness of the modern rabble (or people). But this distinction is not a sufficient explanation of Heidegger’s position, because Heidegger simultaneously seems to hold that even the Germans are characterized by a lack of identity. What is required is a further appropriation of the proper. My suggestion is that this logic of the Volk is not only useful for understanding Heidegger’s thought during the war, but also an indication of what happened after he lost faith in the National Socialist movement and thus had to make the lack of the People the basis of his thought. Keywords Heidegger – Nazism – Schwarze Hefte – Black Notebooks – Volk – people Introduction In § 74 of Sein und Zeit, Heidegger introduces the notorious term “the People” [das Volk]. For Heidegger, this term functions as the intersection between phi- losophy and politics and, consequently, it preoccupies him throughout the turbulent years from the National Socialist revolution in 1933 to the end of WWII in 1945. The shift from individual Dasein to the Dasein of the German People has often been noted as the very point at which Heidegger’s fundamen- tal ontology intersects with his disastrous political views. -

Beyond the Racial State

Beyond the Racial State Rethinking Nazi Germany Edited by DEVIN 0. PENDAS Boston College MARK ROSEMAN Indiana University and · RICHARD F. WETZELL German Historical Institute Washington, D.C. GERMAN lflSTORICAL INSTITUTE Washington, D.C. and CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS I Racial Discourse, Nazi Violence, and the Limits of the Racial State Model Mark Roseman It seems obvious that the Nazi regime was a racial state. The Nazis spoke a great deal about racial purity and racial difference. They identified racial enemies and murdered them. They devoted considerable attention to the health of their own "race," offering significant incentives for marriage and reproduction of desirable Aryans, and eliminating undesirable groups. While some forms of population eugenics were common in the interwar period, the sheer range of Nazi initiatives, coupled with the Nazis' willing ness to kill citizens they deemed physically or mentally substandard, was unique. "Racial state" seems not only a powerful shorthand for a regime that prioritized racial-biological imperatives but also above all a pithy and plausible explanatory model, establishing a strong causal link between racial thinking, on the one hand, and murderous population policy and genocide, on the other. There is nothing wrong with attaching "racial. state" as a descriptive label tci the Nazi regime. It successfully connotes a regime that both spoke a great deal about race and acted in the name of race. It enables us to see the links between a broad set of different population measures, some positively discriminatory, some murderously eliminatory. It reminds us how sttongly the Nazis believed that maximizing national power depended on managing the health and quality of the population. -

The Weather in Germany in Spring 2021

Press Release The weather in Germany – Spring 2021 Coldest spring since 2013 – but average sunshine Offenbach, 31 May 2021 – Spring 2021 was much too cool. Thus, the series of excessively warm springs in Germany, which had started in 2013, came to an end. The cool north winds in April and the inflow of fresh maritime air in May, in particular, kept average temperatures low. Summery weather only made a brief appearance. Whereas the amount of precipitation was less than the long-term average, the sunshine duration was slightly higher than normal. This is the summary announced by the Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) after an initial analysis of the observations from its approximately 2,000 measuring stations. A mild March was followed by a very cool April and May At 7.2 degrees Celsius (°C), the average temperature in spring 2021 was 0.5 degrees lower than the international reference value 1961–1990. Compared to the current 1991–2020 reference period, the deviation was -1.7 degrees. The factors that determined the negative deviation were the coldest April for 40 years and the cool May. Before this, March had brought fluctuating temperatures. Germany only enjoyed a brief high summer intermezzo for Mother's Day on 9 May. During this time, Waghäusel-Kirrlach, to the south-west of Heidelberg, registered the first hot day of 2021 (> 30 °C) with a temperature of 31.3 °C, which was also the hottest spring temperature nationwide. The lowest temperature was recorded on 6 April at Messstetten on the Swabian Alb (-13.6 °C). Little precipitation in the north-east in contrast to plenty of precipitation in the south per square metre (l/m²): at around 175 l/m2, it was only 93 per cent of the long-term average. -

Paper 3 Weimar and Nazi Germany Revision Guide and Student Activity Book

Paper 3 Weimar and Nazi Germany Revision Guide and Student Activity Book Section 1 – Weimar Republic 1919-1929 What was Germany like before and after the First World War? Before the war After the war The Germans were a proud people. The proud German army was defeated. Their Kaiser, a virtual dictator, was celebrated for his achievements. The Kaiser had abdicated (stood down). The army was probably the finest in the world German people were surviving on turnips and bread (mixed with sawdust). They had a strong economy with prospering businesses and a well-educated, well-fed A flu epidemic was sweeping the country, killing workforce. thousands of people already weakened by rations. Germany was a superpower, being ruled by a Germany declared a republic, a new government dictatorship. based around the idea of democracy. The first leader of this republic was Ebert. His job was to lead a temporary government to create a new CONSTITUTION (SET OF RULES ON HOW TO RUN A COUNTRY) Exam Practice - Give two things you can infer from Source A about how well Germany was being governed in November 1918. (4 marks) From the papers of Jan Smuts, a South African politician who visited Germany in 1918 “… mother-land of our civilisation (Germany) lies in ruins, exhausted by the most terrible struggle in history, with its peoples broke, starving, despairing, from sheer nervous exhaustion, mechanically struggling forward along the paths of anarchy (disorder with no strong authority) and war.” Inference 1: Details in the source that back this up: Inference 2: Details in the source that back this up: On the 11th November, Ebert and the new republic signed the armistice. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

Indictment Presented to the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg, 18 October 1945)

Indictment presented to the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg, 18 October 1945) Caption: On 18 October 1945, the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg accuses 24 German political, military and economic leaders of conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity. Source: Indictment presented to the International Military Tribunal sitting at Berlin on 18th October 1945. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, November 1945. 50 p. (Cmd. 6696). p. 2-50. Copyright: Crown copyright is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office and the Queen's Printer for Scotland URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/indictment_presented_to_the_international_military_tribunal_nuremberg_18_october_1945-en- 6b56300d-27a5-4550-8b07-f71e303ba2b1.html Last updated: 03/07/2015 1 / 46 03/07/2015 Indictment presented to the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg, 18 October 1945) INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, AND THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS — AGAINST — HERMANN WILHELM GÖRING, RUDOLF HESS, JOACHIM VON RIBBENTROP, ROBERT LEY, WILHELM KEITEL, ERNST KALTEN BRUNNER, ALFRED ROSENBERG, HANS FRANK, WILHELM FRICK, JULIUS STREICHER, WALTER FUNK, HJALMAR SCHACHT, GUSTAV KRUPP VON BOHLEN UND HALBACH, KARL DÖNITZ, ERICH RAEDER, BALDUR VON SCHIRACH, FRITZ SAUCKEL, ALFRED JODL, MARTIN BORMANN, FRANZ VON PAPEN, ARTUR SEYSS INQUART, ALBERT SPEER, CONSTANTIN VON NEURATH, AND HANS FRITZSCHE, -

Gerr"1AN IDENT ITV TRANSFORNED

GERr"1AN IDENT ITV TRANSFORNED 1. Is GePmany a SpeciaZ Case? German identity problems are usually viewed as a special case. I do not think it is necessary to argue this point with any elabor ation. It is argued that the Germans' obsessions about identity reached a peak of mental aberration in the Second World War, when in a fit of total national insanity they set about mass murdering most of Europe on the grounds of arbitrary and invented grades of approved and disapproved races, drawn from a misunderstanding of physical anthropology. The sources of the identity problem have been subjected to a great deal of analysis, but remain obscure. l Before I go on to look at how true it is that German identity poses special problems, let me briefly mention a recent example of the extent to which the attitudes drawn from the Second World War have permeated our consciousness. I enjoy science fiction, and last summer I watched a film on TV, made in America by a consortium of apparently largely Mafia money, which concerned the invasion of the earth from outer space. The invaders were lizards from another solar system. They were lizards who were able to make themselves look like people by wearing a synthetic human skin, but underneath were reptiles. Some clever people observed this from the beginning, but were disbelieved. The lizards seemed friendly, and quickly acquired what were called collaborators, drawn from the ambitious and weak elements in society. Lizards played on conservative instincts, such as a desire for law and order. -

A Comparative Study of the Conception and Changes of the German Woods by Germans Throughout History Seen Through Art

A comparative study of the conception and changes of the German woods by Germans throughout history seen through art Anna Henryson 13015491 Module: CP6013 BA Fine Art (Photography) The Cass Dissertation April/2016 Contents List of illustrations I. Introduction II. 19th century III. Nature preservation and the forgotten art IV. The German woods in the present V. Conclusion Bibliography 2 List of Illustrations 1. Maps of the World, Map of Germany, 2013, p. 6. 2. Carl Wilhelm Kolbe, Study of oak trees (recto), 1800, p. 9. 3. Caspar David Friedrich, The Chasseur in the Forest, 1814, p. 10. 4. Caspar David Friedrich, The Cross in the Mountains, 1812, p. 11. 5. Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818, p. 12. 6. Ernst Barlach, The Seventh Day (Der siebente Tag) from The Transformations of God (Die Wandlungen Gottes), 1922, p. 15. 7. Hans Thoma, The Hiker in the Black Forest, 1891, p. 17. 8. Werner Piener, Hügellandschaft mit Feldern, p. 18. 9. Anselm Kiefer, Occupations, 1969, p. 19. 10. Anselm Kiefer, Varus, 1976, p. 20. 11. Joseph Beuys, Feuerstätte I und Feuerstätte II (Hearth I and Hearth II), 1968–74 and 1978–9, p. 22. 12. Joseph Beuys, 7000 Oak Trees, 1982, © DACS, 2016, p. 23. 3 Introduction ‘A well ordered ideal of ecology… can only stem from art… Art is then, a genuinely human medium for revolutionary change in the sense of completing the transformation from a sick world to a healthy one.’1 A quote from Joseph Beuys, one of the leading artists during the later part of the 20th century and one of the co-founders of the Green Party in Germany.