Shifting Currents: a History of Rivers, Control and Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gibraltar Range Parks and Reserves

GIBRALTAR RANGE GROUP OF PARKS (Incorporating Barool, Capoompeta, Gibraltar Range, Nymboida and Washpool National Parks and Nymboida and Washpool State Conservation Areas) PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Part of the Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) February 2005 This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for the Environment on 8 February 2005. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This draft plan of management was prepared by the Northern Directorate Planning Group with assistance from staff of the Glen Innes East and Clarence South Areas of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. The contributions of the Northern Tablelands and North Coast Regional Advisory Committees are greatly appreciated. Cover photograph: Coombadjha Creek, Washpool National Park. © Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) 2005: Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgment. ISBN 0 7313 6861 4 i FOREWORD The Gibraltar Range Group of Parks includes Barool, Capoompeta, Gibraltar Range, Nymboida and Washpool National Parks and Nymboida and Washpool State Conservation Areas. These five national parks and two state conservation areas are located on the Gibraltar Range half way between Glen Innes and Grafton, and are transected by the Gwydir Highway. They are considered together in this plan because they are largely contiguous and have similar management issues. The Gibraltar Range Group of Parks encompasses some of the most diverse and least disturbed forested country in New South Wales. The Parks contain a stunning landscape of granite boulders, expansive rainforests, tall trees, steep gorges, clear waters and magnificent scenery over wilderness forests. Approximately one third of the area is included on the World Heritage list as part of the Central Eastern Rainforest Reserves of Australia (CERRA). -

No. XIII. an Act to Provide More Effectually for the Representation of the People in the Legis Lative Assembly

No. XIII. An Act to provide more effectually for the Representation of the people in the Legis lative Assembly. [12th July, 1880.] HEREAS it is expedient to make better provision for the W Representation of the People in the Legislative Assembly and to amend and consolidate the Law regulating Elections to the Legisla tive Assembly Be it therefore enacted by the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty by and with the advice and consent of the Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly of New South Wales in Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same as follows :— Preliminary. 1. In this Act the following words in inverted commas shall have the meanings set against them respectively unless inconsistent with or repugnant to the context— " Governor"—The Governor with the advice of the Executive Council. "Assembly"—The Legislative Assembly of New South Wales. " Speaker"—The Speaker of the Assembly for the time being. " Member"—Member of the Assembly. "Election"—The Election of any Member or Members of the Assembly. " Roll"—The Roll of Electors entitled to vote at the election of any Member of the Assembly as compiled revised and perfected under the provisions of this Act. "List"—-Any List of Electors so compiled but not revised or perfected as aforesaid. " Collector"—Any duly appointed Collector of Electoral Lists. "Natural-born subject"—Every person born in Her Majesty's dominions as well as the son of a father or mother so born. " Naturalized subject"—Every person made or hereafter to be made a denizen or who has been or shall hereafter be naturalized in this Colony in accordance with the Denization or Naturalization laws in force for the time being. -

The Influence of Learning on a Tourism Destination Community's Responses

The influence of learning on a tourism destination community’s responses to the impacts of climate change Thi Duyen Anh Pham Master of Social Planning and Development Bachelor of Science A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 School of Business Abstract Climate change presents significant challenges for the sustainability of the tourism sector. Tourism destinations in developing countries have been identified as the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change; however, little is known about the situation of climate change and the tourism sector in the developing world, despite the relative importance of tourism to the local economies. Building adaptive capacity is important to increase the capability of the local destination community stakeholders to manage the impacts of climate change on their business and on the broader destination. Considerable adaptation research has been conducted; however, adaptation discourses in the tourism sector are still predominantly focused on responding to the predicted impacts of future climate change rather than addressing the underlying factors that affect the vulnerability and adaptive capacity of tourism destinations and local community stakeholders. Recent research in social ecological systems has indicated that learning is an essential aspect of building adaptive capacity. In this context, social learning is emerging as an adaptation approach that addresses issues hindering adaptation, such as a lack of knowledge and awareness, and encourages a proactive response by human systems to climate change. Underpinned by the theories of climate change adaptation and social learning, this research seeks to understand the influence of learning on a destination community’s responses to the impacts of climate change. -

Northern Tablelands Region Achievement Report 2015-2016 M Price

Northern Tablelands Region Achievement Report 2015-2016 M Price WHO WE ARE KEY PARTNERSHIPS Reserves in the east protect mountain and ................................................................................................ ................................................................................................ gorge country landscapes which include The Northern Tablelands Region manages We work with and for our communities in rainforests of the Gondwana Rainforests of over 592,000 hectares, in 93 reserves spread conserving, protecting and managing the Australia World Heritage site, high altitude over the escarpments, tablelands and very significant values of our parks, and granite peaks and the wild rivers of the western slopes of northern NSW. in providing opportunities for engaging Macleay River catchment. experiences. The Strategic Programs Team and Regional Across the region’s rural tablelands Administrative Support Team work from We foster important partnerships with and slopes, significant areas have been our Armidale office, and there are three Aboriginal groups, reserve neighbours, protected, such as Torrington State management areas: Walcha, Glen Innes and communities in adjoining towns and villages, Conservation Area, Warrabah National Park Tenterfield. We also have depots in Armidale, local government, the Rural Fire Service, and Kwiambal National Park, where unique Yetman and Bingara. Local Land Services, Forestry Corporation, landscapes and remnants of the original local members of NSW Parliament and New England -

Public Leadership—Perspectives and Practices

Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Edited by Paul ‘t Hart and John Uhr Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/public_leadership _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Public leadership pespectives and practices [electronic resource] / editors, Paul ‘t Hart, John Uhr. ISBN: 9781921536304 (pbk.) 9781921536311 (pdf) Series: ANZSOG series Subjects: Leadership Political leadership Civic leaders. Community leadership Other Authors/Contributors: Hart, Paul ‘t. Uhr, John, 1951- Dewey Number: 303.34 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Images comprising the cover graphic used by permission of: Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development Australian Associated Press Australian Broadcasting Corporation Scoop Media Group (www.scoop.co.nz) Cover graphic based on M. C. Escher’s Hand with Reflecting Sphere, 1935 (Lithograph). Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2008 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University. He is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). -

Fossickers Way

Fossickers Way Fossickers Way OPEN IN MOBILE Jacaranda trees line a street in the country town of Tamworth Details Open leg route 559.4KM / 347.6MI (Est. travel time 7 hours) Brush up on gold rush history in the rolling green hills of NSW's gorgeous gemstone country. Wind along sun-dappled country roads from Barraba to Tamworth, fossick for hidden gems, and explore historic colonial towns and spectacular national parks. What is a QR code? To learn how to use QR codes refer to the last page 1 of 29 Fossickers Way What is a QR code? To learn how to use QR codes refer to the last page 2 of 29 Fossickers Way 1 Day 1: Barraba OPEN IN MOBILE The trail kicks o in the character-Êlled New England town of Barraba, hugging a picturesque bend of the Manilla River between the Horton Valley and the beautiful Nandewar Ranges. With its tree-lined streets, heritage buildings and old fashioned shop fronts, Barraba is a delightful gold rush town dating back to the mid 1800s. The area is a haven for birdwatchers and rare 40m mural artwork on Barraba Silos by artist Fintan Magee birds alike, including the endangered Regent Honeyeater and 190 other bird species. Part of the Silo Art Trail, keep an eye out for the amazing 40m high Barraba Silo mural, The Water Diviner, on your way into town. You can while away a pleasant afternoon at the Split Rock Dam, a popular spot for local Êshing and water sports. Don’t miss the dramatic rock formations of Mount Kaputar National Park, an extinct volcano surrounded by remnant rainforest with bushwalking trails, abundant wildËowers and towering snow gums. -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 12 Friday, 1 February 2008 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

223 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 12 Friday, 1 February 2008 Published under authority by Government Advertising LEGISLATION Proclamations New South Wales Commencement Proclamation under the Police Amendment Act 2007 No 68 MARIE BASHIR,, GovernorGovernor I, Professor Marie Bashir AC, CVO, Governor of the State of New South Wales, with the advice of the Executive Council, and in pursuance of section 2 of the Police Amendment Act 2007, do, by this my Proclamation, appoint 4 February 2008 as the day on which the uncommenced provisions of that Act commence. SignedSigned andand sealedsealed atat Sydney,Sydney, thisthis 30th day of January day of 2008. 2008. By Her Excellency’s Command, DAVID CAMPBELL, M.P., L.S. MinisterMinister for for Police Police GOD SAVE THE QUEEN! Explanatory note The object of this Proclamation is to commence the uncommenced provisions of the Police Amendment Act 2007, including provisions relating to employment matters and complaints made against police. s2008-020-30.d03 Page 1 224 LEGISLATION 1 February 2008 Regulations New South Wales Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Section 94A Levies) Regulation 2008 under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 Her Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has made the following Regulation under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979. FRANK SARTOR, M.P., Minister for Planning Explanatory note The object of this Regulation is to provide that, for development within the area to which Newcastle City Centre Local Environmental Plan 2008 applies that has a proposed cost of more than $250,000, the maximum section 94A levy that may be imposed is 3 per cent of the proposed cost of that development. -

The Bicentennial National Trail (3Rd Edition 2006) Guide Book Number

The Bicentennial National Trail (3rd Edition 2006) Guide Book Number 7 Trail Updates July 2018 Page 1 of 7 BNT office 1300 138 724 [email protected] Guide books [email protected] The Bicentennial National Trail is “a living trail” and as such conditions and access details are continually changing. Some of the information in the ‘update notes’ may have been provided by trekkers and may not have been verified on the ground by the section coordinator or a BNT Board member. Update notes are only a guide and situations can change from day to day therefore, you must try to contact the section coordinator and not rely solely on the guidebook or the update notes. You travel at your own risk as travelling on the BNT is regarded as self-reliant trekking. Note that these updates are to be used in conjunction with the guidebook identified above. Could all trekkers please send any information on track changes to the BNT office so the update notes can be as current as possible. Your notes need to be clear and concise. Please contact your local coordinator prior to trekking to advise of approximate travel dates and to obtain an update on local conditions. Can you also notify the office or section coordinator of any problems you may encounter, thank you. Happy trekking. DO NOT attempt this route after heavy rains as the river crossings are very treacherous when in flood. GUIDE BOOK 7 UPDATES Re-routing of BNT on Map 1 & 2 – Killarney to Wylie Creek Guidebook 7 Glue to pages 28 & 30 Map 1 & 2 Killarney to Wylie Creek. -

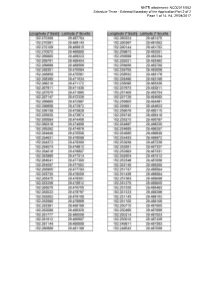

NCD2017/002 Schedule Three

NNTR attachment: NCD2017/002 Schedule Three - External Boundary of the Application Part 2 of 2 Page 1 of 14, A4, 29/08/2017 NNTR attachment: NCD2017/002 Schedule Three - External Boundary of the Application Part 2 of 2 Page 2 of 14, A4, 29/08/2017 Then north westerly to the southernmost corner of an unnamed road which bisects the southern boundary of Lot 1 on DP751494; then generally northerly along the eastern boundaries of that unnamed road to Latitude 29.394977° South; then generally northerly through the following coordinate points; NNTR attachment: NCD2017/002 Schedule Three - External Boundary of the Application Part 2 of 2 Page 3 of 14, A4, 29/08/2017 NNTR attachment: NCD2017/002 Schedule Three - External Boundary of the Application Part 2 of 2 Page 4 of 14, A4, 29/08/2017 NNTR attachment: NCD2017/002 Schedule Three - External Boundary of the Application Part 2 of 2 Page 5 of 14, A4, 29/08/2017 Then northerly to an eastern boundary of the Upper Rocky River road reserve at Latitude 29.334920° South; then generally northerly along the eastern boundaries of that road reserve to Latitude 29.209676° South; then generally northerly through the following coordinate points; Then northerly to again an eastern boundary of Upper Rocky River road reserve at Latitude 29.200911° South; then generally northerly along the eastern boundaries of that road reserve to its intersection with the southern boundary of Billarimba road reserve; then northerly to the northern boundary of that road reserve at Longitude 152.249268° East; then generally north -

Functioning and Changes in the Streamflow Generation of Catchments

Ecohydrology in space and time: functioning and changes in the streamflow generation of catchments Ralph Trancoso Bachelor Forest Engineering Masters Tropical Forests Sciences Masters Applied Geosciences A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Earth and Environmental Sciences Trancoso, R. (2016) PhD Thesis, The University of Queensland Abstract Surface freshwater yield is a service provided by catchments, which cycle water intake by partitioning precipitation into evapotranspiration and streamflow. Streamflow generation is experiencing changes globally due to climate- and human-induced changes currently taking place in catchments. However, the direct attribution of streamflow changes to specific catchment modification processes is challenging because catchment functioning results from multiple interactions among distinct drivers (i.e., climate, soils, topography and vegetation). These drivers have coevolved until ecohydrological equilibrium is achieved between the water and energy fluxes. Therefore, the coevolution of catchment drivers and their spatial heterogeneity makes their functioning and response to changes unique and poses a challenge to expanding our ecohydrological knowledge. Addressing these problems is crucial to enabling sustainable water resource management and water supply for society and ecosystems. This thesis explores an extensive dataset of catchments situated along a climatic gradient in eastern Australia to understand the spatial and temporal variation -

New South Wales Government Gazette No. 41 of 12 October

4321 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 107 Friday, 12 October 2012 Published under authority by the Department of Premier and Cabinet LEGISLATION Online notification of the making of statutory instruments Week beginning 1 October 2012 THE following instruments were officially notified on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) on the dates indicated: Proclamations commencing Acts City of Sydney Amendment (Central Sydney Traffic and Transport Committee) Act 2012 No 47 (2012-498) — published LW 5 October 2012 Crime Commission Act 2012 No 66 (2012-499) — published LW 5 October 2012 Government Advertising Act 2011 No 35 (2012-500) — published LW 5 October 2012 Water Management Act 2000 No 92 (2012-495) — published LW 4 October 2012 Regulations and other statutory instruments Crime Commission Regulation 2012 (2012-501) — published LW 5 October 2012 Criminal Assets Recovery Amendment Regulation 2012 (2012-502) — published LW 5 October 2012 Government Advertising Regulation 2012 (2012-503) — published LW 5 October 2012 Police Amendment (Legal Advice Disclosure) Regulation 2012 (2012-504) — published LW 5 October 2012 Police Amendment (Targeted Tests) Regulation 2012 (2012-505) — published LW 5 October 2012 Water Management (Application of Act to Certain Water Sources) Proclamation (No 2) 2012 (2012-496) — published LW 4 October 2012 Water Management (General) Amendment (Water Sharing Plans) Regulation 2012 (2012-497) — published LW 4 October 2012 Water Sharing Plan for the Barwon-Darling Unregulated and -

Yuraygir National Park Contextual History

Yuraygir National Park Contextual History A report for the Cultural Landscapes: Connecting History, Heritage and Reserve Management research project This report was written by Johanna Kijas. Many thanks to Roy Bowling, Marie Preston, Rosemary Waugh-Allcock, Allen Johnson, Joyce Plater, Shirley Causley, Clarrie and Shirley Winkler, Bill Niland and Peter Morgan for their vivid memories of the pre- and post-national park landscape. Particular thanks to Rosemary Waugh-Allcock for her hospitality and sharp memory of a changing place, and to Joyce Plater for her resources and interest in the project. Thanks to long-term visitors to the Pebbly Beach camping area who consented to be interviewed over the phone, and Ian Brown for his memories of trips to Freshwater. Thanks to Ken Teakle for taking the time to provide DECC with copies of his photographic history of Pebbly Beach, and to Barbara Knox for permission to use her interview carried out with Gina Hart. Cover photo: Johanna Kijas. Published by: Department of Environment and Climate Change 59–61 Goulburn Street PO Box A290 Sydney South 1232 Ph: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Ph: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Ph: 1300 361 967 (national parks information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN: 978 1 74122 455 9 DECC: 2007/265 November 2007 Contents Executive summary Section 1: Overview and maps 1 1.1 Introduction: a contextual history of Yuraygir National Park 1