Yuraygir National Park Contextual History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dpaper June13

Dundurrabin Community News June, 2013 Volume 5, Issue 2 Dundurrabin Community Centre News At the AGM in March a new in getting some badly needed important to keep it as a committee was elected. Several maintenance completed and community meeting place. existing members decided not We will be holding a monster to continue and we’d like to Working Bee / Community get- thank Marnie and Allan Carr, BEE together on Sat 29th June. Glenda Harvey and Di Clark for WORKING Dinner their valuable contributions in Community We’re hoping to do a big clean the old committee. Trivia Quiz up as well as do a number of improvements. We’d like to welcome Jo Ware and Tracey The committee can’t do it by McClafferty to the new SATURDAY 29TH JUNE themselves. WE NEED YOUR committee which now 10am to 4pm HELP. consists of: At the DUNDURRABIN It doesn’t matter what skills Peter Clark - Chair, COMMUNITY CENTRE you have WE NEED YOUR Jo Ware - Secretary, HELP. Malcolm Stanton - 5pm Bonfire and Community Treasurer, Dinner - to be followed by a If you can spare an hour or two Kate Goode, Trivia Quiz or more please come along Tracey McClafferty and and help. Phil Ward. Working Bee - What to bring - working clothes, whipper The role of the committee The working bee will be from snipper or mower if you can or is, with Council’s help, to 10am till 4pm. This will be gardening hand tools • Clean, maintain and followed at 5pm by a bonfire improve the Centre Community Dinner - A plate of and a Community Dinner food to share, BBQ facilities [please bring a plate of food to • Take bookings for the share] and then a Trivia Quiz. -

Approved Conservation Advice for Rutidosis Heterogama (Heath Wrinklewren)

This Conservation Advice was approved by the Minister/Delegate of the Minister on: 3/07/2008. Approved Conservation Advice (s266B of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999). Approved Conservation Advice for Rutidosis heterogama (Heath Wrinklewren) This Conservation Advice has been developed based on the best available information at the time this conservation advice was approved. Description Rutidosis heterogama, Family Asteraceae, also known as the Heath Wrinklewren or Heath Wrinklewort, is a perennial herb with decumbent (reclining to lying down) to erect stems, growing to 30 cm high (Harden, 1992; DECC, 2005a). The tiny yellow flowerheads are probably borne March to April (Leigh et al., 1984), chiefly in Autumn (Harden, 1992) or November to January. Seeds are dispersed by wind (Clarke et al., 1998) and the species appears to require soil disturbance for successful recruitment (Clarke et al., 1998). Conservation Status Heath Wrinklewren is listed as vulnerable. This species is eligible for listing as vulnerable under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth) (EPBC Act) as, prior to the commencement of the EPBC Act, it was listed as vulnerable under Schedule 1 of the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992 (Cwlth). The species is also listed as vulnerable on the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (NSW). Distribution and Habitat Heath Wrinklewren is confined to the North Coast and Northern Tablelands regions of NSW. It is known from the Hunter Valley to Maclean, Wooli to Evans Head, and Torrington (Harden, 1992). It occurs within the Border Rivers–Gwydir, Hunter–Central Rivers and Northern Rivers (NSW) Natural Resource Management Regions. -

No. XIII. an Act to Provide More Effectually for the Representation of the People in the Legis Lative Assembly

No. XIII. An Act to provide more effectually for the Representation of the people in the Legis lative Assembly. [12th July, 1880.] HEREAS it is expedient to make better provision for the W Representation of the People in the Legislative Assembly and to amend and consolidate the Law regulating Elections to the Legisla tive Assembly Be it therefore enacted by the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty by and with the advice and consent of the Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly of New South Wales in Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same as follows :— Preliminary. 1. In this Act the following words in inverted commas shall have the meanings set against them respectively unless inconsistent with or repugnant to the context— " Governor"—The Governor with the advice of the Executive Council. "Assembly"—The Legislative Assembly of New South Wales. " Speaker"—The Speaker of the Assembly for the time being. " Member"—Member of the Assembly. "Election"—The Election of any Member or Members of the Assembly. " Roll"—The Roll of Electors entitled to vote at the election of any Member of the Assembly as compiled revised and perfected under the provisions of this Act. "List"—-Any List of Electors so compiled but not revised or perfected as aforesaid. " Collector"—Any duly appointed Collector of Electoral Lists. "Natural-born subject"—Every person born in Her Majesty's dominions as well as the son of a father or mother so born. " Naturalized subject"—Every person made or hereafter to be made a denizen or who has been or shall hereafter be naturalized in this Colony in accordance with the Denization or Naturalization laws in force for the time being. -

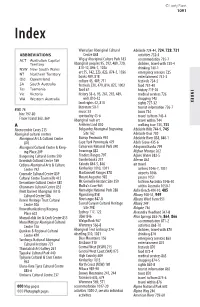

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Landcare in the Clarence Celebrating 25 Years

The History of Landcare in the Clarence celebrating 25 years 1989—2014 Acknowledgements Compiled by Alastair Maple Clarence Landcare Inc. would like to thank the many people who Edited by Carole Bryant contributed photos, newspaper articles, personal time and their own writing for Clarence Landcare Inc.© 2014 and recollections in the compilation of this special publication celebrating Clarence Landcare’s achievements over the past 25 years. Where possible, acknowledgement has been made to the contributor/s. However, this is not Cover photos: Clarence River and always so, and apologies are made to the people concerned for what may Susan Island, Grafton. well appear to them and others as glaring omissions. Photos: Carole Bryant We would also like to thank Clarence Valley Council for their contribution to Clarence Landcare over the past 25 years. A message from Clarence Landcare’s Chairman Twenty-five years ago the National Farmers Federation Landcare in the Clarence has evolved and has become and the Australian Conservation Foundation formed the more holistic in the approach to environmental issues. Landcare movement. The uncommon alliance between those two groups threw significant weight behind the We no longer focus on the restoration and protection of pitch for a Landcare movement. A movement that put a our natural environment. The improvement and enhance- spotlight on the challenges that faced the Australian land- ment of our productive landscapes ties their economic scape and the hope that Landcare would be able to make benefit to the existing environmental and social compo- a difference. nent that is Landcare. Clarence Landcare began with the assistance of the Total Agriculture of the future will see the people of the cities Catchment Management in 1996 as the 4C’s. -

An Ecological History of the Koala Phascolarctos Cinereus in Coffs Harbour and Its Environs, on the Mid-North Coast of New South Wales, C1861-2000

An Ecological History of the Koala Phascolarctos cinereus in Coffs Harbour and its Environs, on the Mid-north Coast of New South Wales, c1861-2000 DANIEL LUNNEY1, ANTARES WELLS2 AND INDRIE MILLER2 1Offi ce of Environment and Heritage NSW, PO Box 1967, Hurstville NSW 2220, and School of Biological Sciences, University of Sydney, NSW 2006 ([email protected]) 2Offi ce of Environment and Heritage NSW, PO Box 1967, Hurstville NSW 2220 Published on 8 January 2016 at http://escholarship.library.usyd.edu.au/journals/index.php/LIN Lunney, D., Wells, A. and Miller, I. (2016). An ecological history of the Koala Phascolarctos cinereus in Coffs Harbour and its environs, on the mid-north coast of New South Wales, c1861-2000. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 138, 1-48. This paper focuses on changes to the Koala population of the Coffs Harbour Local Government Area, on the mid-north coast of New South Wales, from European settlement to 2000. The primary method used was media analysis, complemented by local histories, reports and annual reviews of fur/skin brokers, historical photographs, and oral histories. Cedar-cutters worked their way up the Orara River in the 1870s, paving the way for selection, and the fi rst wave of European settlers arrived in the early 1880s. Much of the initial development arose from logging. The trade in marsupial skins and furs did not constitute a signifi cant threat to the Koala population of Coffs Harbour in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The extent of the vegetation clearing by the early 1900s is apparent in photographs. -

What Role Does Ecological Research Play in Managing Biodiversity in Protected Areas? Australia’S Oldest National Park As a Case Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online What Role Does Ecological Research Play in Managing Biodiversity in Protected Areas? Australia’s Oldest National Park as a Case Study ROSS L. GOLDINGAY School of Environmental Science & Management, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW 2480 Published on 3 September 2012 at http://escholarship.library.usyd.edu.au/journals/index.php/LIN Goldingay, R.L. (2012). What role does ecological research play in managing biodiversity in protected areas? Australia’s oldest National Park as a case study. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 134, B119-B134. How we manage National Parks (protected areas or reserves) for their biodiversity is an issue of current debate. At the centre of this issue is the role of ecological research and its ability to guide reserve management. One may assume that ecological science has suffi cient theory and empirical evidence to offer a prescription of how reserves should be managed. I use Royal National Park (Royal NP) as a case study to examine how ecological science should be used to inform biodiversity conservation. Ecological research relating to reserve management can be: i) of generic application to reserve management, ii) specifi c to the reserve in which it is conducted, and iii) conducted elsewhere but be of relevance due to the circumstances (e.g. species) of another reserve. I outline how such research can be used to inform management actions within Royal NP. I also highlight three big challenges for biodiversity management in Royal NP: i) habitat connectivity, ii) habitat degradation and iii) fi re management. -

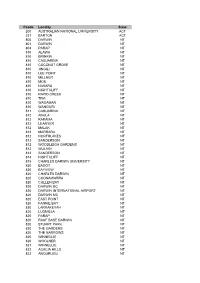

Pcode Locality State 200 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL

Pcode Locality State 200 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY ACT 221 BARTON ACT 800 DARWIN NT 801 DARWIN NT 804 PARAP NT 810 ALAWA NT 810 BRINKIN NT 810 CASUARINA NT 810 COCONUT GROVE NT 810 JINGILI NT 810 LEE POINT NT 810 MILLNER NT 810 MOIL NT 810 NAKARA NT 810 NIGHTCLIFF NT 810 RAPID CREEK NT 810 TIWI NT 810 WAGAMAN NT 810 WANGURI NT 811 CASUARINA NT 812 ANULA NT 812 KARAMA NT 812 LEANYER NT 812 MALAK NT 812 MARRARA NT 812 NORTHLAKES NT 812 SANDERSON NT 812 WOODLEIGH GARDENS NT 812 WULAGI NT 813 SANDERSON NT 814 NIGHTCLIFF NT 815 CHARLES DARWIN UNIVERSITY NT 820 BAGOT NT 820 BAYVIEW NT 820 CHARLES DARWIN NT 820 COONAWARRA NT 820 CULLEN BAY NT 820 DARWIN DC NT 820 DARWIN INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT NT 820 DARWIN MC NT 820 EAST POINT NT 820 FANNIE BAY NT 820 LARRAKEYAH NT 820 LUDMILLA NT 820 PARAP NT 820 RAAF BASE DARWIN NT 820 STUART PARK NT 820 THE GARDENS NT 820 THE NARROWS NT 820 WINNELLIE NT 820 WOOLNER NT 821 WINNELLIE NT 822 ACACIA HILLS NT 822 ANGURUGU NT 822 ANNIE RIVER NT 822 BATHURST ISLAND NT 822 BEES CREEK NT 822 BORDER STORE NT 822 COX PENINSULA NT 822 CROKER ISLAND NT 822 DALY RIVER NT 822 DARWIN MC NT 822 DELISSAVILLE NT 822 FLY CREEK NT 822 GALIWINKU NT 822 GOULBOURN ISLAND NT 822 GUNN POINT NT 822 HAYES CREEK NT 822 LAKE BENNETT NT 822 LAMBELLS LAGOON NT 822 LIVINGSTONE NT 822 MANINGRIDA NT 822 MCMINNS LAGOON NT 822 MIDDLE POINT NT 822 MILIKAPITI NT 822 MILINGIMBI NT 822 MILLWOOD NT 822 MINJILANG NT 822 NGUIU NT 822 OENPELLI NT 822 PALUMPA NT 822 POINT STEPHENS NT 822 PULARUMPI NT 822 RAMINGINING NT 822 SOUTHPORT NT 822 TORTILLA -

Koala Conservation Status in New South Wales Biolink Koala Conservation Review

koala conservation status in new south wales Biolink koala conservation review Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 6 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE NSW POPULATION .............................................................. 6 Current distribution ............................................................................................................... 6 Size of NSW koala population .............................................................................................. 8 4. INFORMING CHANGES TO POPULATION ESTIMATES ....................................... 12 Bionet Records and Published Reports ............................................................................... 15 Methods – Bionet records ............................................................................................... 15 Methods – available reports ............................................................................................ 15 Results ............................................................................................................................ 16 The 2019 Fires .................................................................................................................... 22 Methods ......................................................................................................................... -

Solitary Islands Marine Park Guide

Solitary Islands Marine Park Guide The NSW marine environment is one of our state’s greatest natural assets and Introduction needs to be managed for the greatest wellbeing of the community, now and into the future. The NSW Solitary Islands Marine Park was the first marine park declared in NSW. Located on the Coffs Coast, the park covers more than 70,000 hectares and 100 kilometres of coastline from the northern side of Muttonbird Island at Coffs Harbour north to Plover Island at the entrance to the Sandon River. It extends from the mean high water mark and upper tidal limits of coastal estuaries and lakes, seaward to the three nautical mile limit of NSW waters and includes the entire seabed. The Solitary Islands Marine Park (Commonwealth waters) covers 15,200 hectares on the seaward side of the NSW Solitary Islands Marine Park, out to the 50 metre depth contour. The Solitary Islands Marine Park (Commonwealth waters) is managed in partnership by the NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) Fisheries and Parks Australia. The NSW Solitary Islands Marine Park management rules protect the marine biodiversity of the area while supporting a wide range of social, cultural and economic values. This guide and accompanying map summarise the management rules for the NSW Solitary Islands Marine Park. For information on Solitary Islands Marine Park (Commonwealth waters) management zones please refer to the map that accompanies this guide or contact Parks Australia. 2 SOLITARY ISLANDS MARINE PARK (NSW) & SOLITARY ISLANDS MARINE PARK (COMMONWEALTH WATERS) GUIDE provides opportunities for swimming, surfing, snorkelling, Unique environmental diving, boating, fishing, walking, and panoramic ocean vistas. -

Clarence River Unregulated and Alluvial 2016

Water Sharing Plan for the Clarence River Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources 2016 [2016-381] New South Wales Status information Currency of version Current version for 6 January 2017 to date (accessed 17 February 2020 at 11:30) Legislation on this site is usually updated within 3 working days after a change to the legislation. Provisions in force The provisions displayed in this version of the legislation have all commenced. See Historical Notes Note: This Plan ceases to have effect on 30.6.2026—see cl 3. Authorisation This version of the legislation is compiled and maintained in a database of legislation by the Parliamentary Counsel's Office and published on the NSW legislation website, and is certified as the form of that legislation that is correct under section 45C of the Interpretation Act 1987. File last modified 6 January 2017. Published by NSW Parliamentary Counsel’s Office on www.legislation.nsw.gov.au Page 1 of 113 Water Sharing Plan for the Clarence River Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources 2016 [NSW] Water Sharing Plan for the Clarence River Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources 2016 [2016-381] New South Wales Contents Part 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................. 7 Note .................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 1 Name of Plan....................................................................................................................................................... -

Shifting Currents: a History of Rivers, Control and Change

Shifting Currents: A history of rivers, control and change Damian Lucas A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Technology, Sydney 2004 Certificate of Authorship / Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. ________________________________________ Damian Lucas Table of contents List of illustrations ii Abbreviations iii Abstract iv Acknowledgements vi Introduction Rivers, meanings and modification 1 I: Controlling Floods – Clarence River 1950s and 1960s 1. Transforming the floodplain 26 2. Drained too deep: Recognising damage from drainage 55 II. Capturing water – Balonne River 1950s and 1960s 3. Improving country, developing water resources 86 4. Steadying the flows: Noticing decline from modification 110 III. Reassessing modification – Clarence River 1980s and 1990s 5. A mysterious fish disease: Recognising damage from development 131 6. Pressing for a healthy river on the ‘lifestyle’ coast 167 IV. Continuing support for modification – Balonne River 1990s 7. A new wave of development: Revitalising the region 197 8. Water for the rivers: New support for river health 222 Conclusion The politics of water: Recognising the benefits and costs of modifying 247 rivers Bibliography 259 Appendix Five Feet High and Rising, Radio Feature [CD] i List of illustrations Introduction 1.