Snakes of Ontario Identifier Introduction Eastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nelsons Milk Snake

Nelsons Milk SNake PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION: • This species of milk snake typically keeps to southern and central Mexico, but have been • The red rings on a Nelson’s milk snake found on some tropical/costal islands as well. range from around 13 to 18, and has a predominantly black snout (except for DIET: when albino). • These snakes will consume various types • The red bands on the nelson’s milk snake are of rodents, amphibians, lizards and even the thickest stripes on their bodies, with black other snakes. being slightly thinner, and white being the thinnest. • Due to their cannibalistic nature nelson’s milk snakes must be housed separately SIZE AND LIFESPAN: when not breeding. • Adult nelson’s milk snakes are a small REPRODUCTION: to medium size snake, averaging around 42 inch (106cm). • Mating in the wild takes place in late spring and early summer. • The lifespan of these snakes is around 12-15 years, but has been known to live to 20 years • The female will select a nest site that is warm of age in captivity! and humid, and will then lays her clutch which contains up to 15 eggs. NATIVE HABITAT: • This species is often found in costal bushes and tropical forests, which provided them with many hiding spots that can protect them. • They are typically found in Mexico, ranging from southern Guanajuato and central Jalisco, all the way to the Pacific Coast. FUN FACTS: • The Nelson’s milk snake is a subspecies of king snakes. • They are nonvenomous, but are typically very shy and take a while to get use to being handled. -

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S: A Reference to Snake Identification, Field Safety, Basic Safe Capture and Handling Methods and First Aid Measures for Reptile Envenomation Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, William M. Niederhofer ACO & John Wisser MS. Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 (Wozniak) City Of Pearland Animal Control, 2002 Old Alvin Rd. Pearland, Texas 77581 (Niederhofer) 464 County Road 949 E Alvin, Texas 77511 (Wisser) Corresponding Author: Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 [email protected] ABSTRACT: Each year numerous emergency response personnel including animal control officers, police officers, wildlife rehabilitators, public health officers and others either respond to calls involving venomous snakes or are forced to venture into the haunts of these animals in the scope of their regular duties. North America is home to two distinct families of native venomous snakes: Viperidae (rattlesnakes, copperheads and cottonmouths) and Elapidae (coral snakes) and southeastern Texas has indigenous species representing both groups. While some of these snakes are easily identified, some are not and many rank amongst the most feared and misunderstood animals on earth. This article specifically addresses all of the native species of venomous snakes that inhabit Health Service Region 6/5s and is intended to serve as a reference to snake identification, field safety, basic safe capture and handling methods and the currently recommended first aide measures for reptile envenomation. -

Lizards & Snakes: Alive!

LIZARDSLIZARDS && SNAKES:SNAKES: ALIVE!ALIVE! EDUCATOR’SEDUCATOR’S GUIDEGUIDE www.sdnhm.org/exhibits/lizardsandsnakeswww.sdnhm.org/exhibits/lizardsandsnakes Inside: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Must-Read Key Concepts and Background Information • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Activities to Extend Learning Back in the Classroom • Map of the Exhibition to Guide Your Visit • Correlations to California State Standards Special thanks to the Ellen Browning Scripps Foundation and the Nordson Corporation Foundation for providing underwriting support of the Teacher’s Guide KEYKEY CONCEPTSCONCEPTS Squamates—legged and legless lizards, including snakes—are among the most successful vertebrates on Earth. Found everywhere but the coldest and highest places on the planet, 8,000 species make squamates more diverse than mammals. Remarkable adaptations in behavior, shape, movement, and feeding contribute to the success of this huge and ancient group. BEHAVIOR Over 45O species of snakes (yet only two species of lizards) An animal’s ability to sense and respond to its environment is are considered to be dangerously venomous. Snake venom is a crucial for survival. Some squamates, like iguanas, rely heavily poisonous “soup” of enzymes with harmful effects—including on vision to locate food, and use their pliable tongues to grab nervous system failure and tissue damage—that subdue prey. it. Other squamates, like snakes, evolved effective chemore- The venom also begins to break down the prey from the inside ception and use their smooth hard tongues to transfer before the snake starts to eat it. Venom is delivered through a molecular clues from the environment to sensory organs in wide array of teeth. -

Copperhead & Endangered Species Agkistrodon Contortrix

Natural Heritage Copperhead & Endangered Species Agkistrodon contortrix Program State Status: Endangered www.mass.gov/nhesp Federal Status: None Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife DESCRIPTION: Copperheads get their name due to their solid, relatively unmarked, coppery-colored head resembling the color of an old copper coin. As with all pit vipers, Copperheads have broad, triangularly shaped heads, with a distinct narrowing just behind the head. The eyes have vertically elliptical (catlike) pupils. There is a very thin line on each side of the face that separates the richer copper color of the top of the head from the lighter color of the lip area. The iris of the eye is pale gold, and the pupil is dark. On the body there is a series of dark brown to reddish, hourglass-shaped, cross bands. These are narrow in the middle of the body and broad to the sides. The ground color ranges from beige to tan. Body markings are continuous over the entire length of the body, including the tail. Young snakes are replicas of adults, except that the body has an overtone of light grey and the tip of the tail is yellow. Adult from Hampshire County; photo by Mike Jones/MassWildlife Adult Copperheads usually measure 60–90 cm (24–36 inches) in length; the newborn young are usually 18–23 ridge protrudes from the middle of each scale), giving cm (7–9 inches). Males usually have longer tails, but the snake a relatively rough-skinned appearance. females can grow to greater total lengths (up to 4 feet). There is no reliable external cue to differentiate the SIMILAR SPECIES IN MASSACHUSETTS: The sexes. -

Eastern Milksnake,Lampropeltis Triangulum

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2014 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2014. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 61 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 29 pp. Fischer, L. 2002. COSEWIC status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-29 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Jonathan Choquette for writing the status report on the Eastern Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum) in Canada. This report was prepared under contract with Environment Canada and was overseen by Jim Bogart, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Amphibians and Reptiles Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Couleuvre tachetée (Lampropeltis triangulum) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Eastern Milksnake — Sketch of the Eastern Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum). -

Snakes of New York State

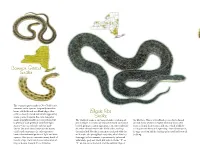

Common Garter Snake ˜e common garter snake is New York’s most common snake species, frequently found in lawns, old ÿelds and woodland edges. One Black Rat of three closely related and similar appearing snake species found in the state, the garter Snake snake is highly variable in color pattern, but ˜e black rat snake is our longest snake, reaching six the blotches. ˜is is a woodland species, but is found is generally dark greenish with three light feet in length. Its scales are uniformly black and faintly around barns where it is highly desirable for its abil- stripes—one on each side and one mid- keeled, giving it a satiny appearance. In some individu- ity to seek and destroy mice and rats, which it kills by dorsal. ˜e mid-dorsal stripe can be barely als, white shows between the black scales, making coiling around them and squeezing. Around farmyards, visible and sometimes the sides appear to the snake look blotchy. Sometimes confused with the its eggs are o˛en laid in shavings piles used for livestock have a checkerboard pattern of light and dark milk snake, the young black rat snake, which hatches bedding. squares. ˜is species consumes many kinds of from eggs in late summer, is prominently patterned insects, slugs, worms and an occasional small with white, grey and black, but lacks both the “Y” or frog or mouse. Length: 16 to 30 inches. “V” on the top of the head, and the reddish tinge to Timber Rattlesnake Copperhead ˜e copperhead is an attractively-patterned, venomous snake with a pinkish-tan color super- imposed on darker brown to chestnut colored saddles that are narrow at the spine and wide at the sides. -

Amphibians and Reptiles Of

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Amphibians and Reptiles of Aransas National Wildlife Refuge Abundance Common Name Abundance Common Name Abundance C Common; suitable habitat is available, Scientific Name Scientific Name should not be missed during appropriate season. Toads and Frogs Texas Tortoise R Couch’s Spadefoot C Gopherus berlandieri U Uncommon; present in moderate Scaphiopus couchi Guadalupe Spiny Soft-shelled Turtle R numbers (often due to low availability Hurter’s Spadefoot C Trionyx spiniferus guadalupensis of suitable habitat); not seen every Scaphiopus hurteri Loggerhead O visit during season Blanchard’s Cricket Frog U Caretta caretta Acris crepitans blanchardi Atlantic Green Turtle O O Occasional; present, observed only Green Tree Frog C Chelonia mydas mydas a few times per season; also includes Hyla cinerea Atlantic Hawksbill O those species which do not occur year, Squirrel Tree Frog U Eretmochelys imbricata imbricata while in some years may be Hyla squirella Atlantic Ridley(Kemp’s Ridley) O fairly common. Spotted Chorus Frog U Lepidocheyls kempi Pseudacris clarki Leatherback R R Rare; observed only every 1 to 5 Strecker’s Chorus Frog U Dermochelys coriacea years; records for species at Aransas Pseudacris streckeri are sporadic and few. Texas Toad R Lizards Bufo speciosus Mediterranean Gecko C Introduction Gulf Coast Toad C Hemidactylus turcicus turcicus Amphibians have moist, glandular skins, Bufo valliceps valliceps Keeled Earless Lizard R and their toes are devoid of claws. Their Bullfrog C Holbrookia propinqua propinqua young pass through a larval, usually Rana catesbeiana Texas Horned Lizard R aquatic, stage before they metamorphose Southern Leopard Frog C Phrynosoma cornutum into the adult form. -

Snakes of New Jersey Brochure

Introduction Throughout history, no other group of animals has undergone and sur- Snakes: Descriptions, Pictures and 4. Corn snake (Elaphe guttata guttata): vived such mass disdain. Today, in spite of the overwhelming common 24”-72”L. The corn snake is a ➣ Wash the bite with soap and water. Snakes have been around for over 100,000,000 years and despite the Range Maps state endangered species found odds, historically, 23 species of snakes existed in New Jersey. However, sense and the biological facts that attest to the snake’s value to our 1. Northern water snake (Nerodia sipedon sipedon): ➣ Immobilize the bitten area and keep it lower than your environment, a good portion of the general public still looks on the in the Pine Barrens of NJ. It heart. most herpetologists believe the non-venomous queen snake is now 22”-53”L. This is one of the most inhabits sandy, forested areas SNAKES OF extirpated (locally extinct) in New Jersey. 22 species of snakes can still snake as something to be feared, destroyed, or at best relegated to common snakes in NJ, inhabit- preferring pine-oak forest with be found in the most densely populated state in the country. Two of our glassed-in cages at zoos. ing freshwater streams, ponds, an understory of low brush. It ➣ lakes, swamps, marshes, and What not to do if bitten by a snake species are venomous, the timber rattlesnake and the northern All snakes can swim, but only the northern water snake and may also be found in hollow queen snake rely heavily on waterbodies. -

Thirty-Nine Species of Snakes Inhabit Illinois, Dwelling in Forests, Grasslands

I l l i n o i s yellowbelly water snake Nerodia erythrogaster SNAKESSNAKES eastern hognose snake Heterodon platirhinos eastern worm snake Carphophis amoenus racer Coluber constrictor western ribbon snake Thamnophis proximus Graham’s crayfish snake Regina grahamii northern water snake Nerodia sipedon western mud snake Farancia abacura smooth earth snake Virginia valeriae common garter snake Thamnophis sirtalis redbelly snake Storeria occipitomaculata western fox snake Pantherophis vulpinus prairie kingsnake Lampropeltis calligaster bullsnake Pituophis catenifer diamondback water snake Nerodia rhombifer common kingsnake Lampropeltis getula red milk snake Lampropeltis triangulum syspila brown snake Storeria dekayi rough green snake Opheodrys aestivus black rat snake juvenile cottonmouth juvenile ringneck snake Diadophis punctatus black rat snake Pantherophis spiloides cottonmouth Agkistrodon piscivorus timber rattlesnake juvenile copperhead juvenile eastern massasauga juvenile timber rattlesnake Crotalus horridus copperhead Agkistrodon contortrix eastern massasauga Sistrurus catenatus Species List Family Colubridae This poster was made possible by: eastern worm snake Carphophis amoenus hirty-nine species of snakes inhabit Illinois, dwelling in forests, grasslands, marshes, swamps, ponds, racer Coluber constrictor ringneck snake Diadophis punctatus western mud snake Farancia abacura Illinois Department of Natural Resources lakes, streams, rivers, and sloughs. Some species are quite common, while others are very rare. These eastern hognose snake Heterodon platirhinos prairie kingsnake Lampropeltis calligaster Division of Education common kingsnake Lampropeltis getula Division of Natural Heritage reptiles are solitary predators that eat a variety of prey. Snakes have interesting structural features Classification: red milk snake Lampropeltis triangulum syspila T yellowbelly water snake Nerodia erythrogaster Illinois State Museum Kingdom Animalia diamondback water snake Nerodia rhombifer including the Jacobson’s organ, which is used to detect odors. -

Honduran Milk Snake

Honduran Milk Snake (Lampropeltis Triangulum Hondurensis) Adult Size 2 ft. to 6 ft. depending Life Span 10-15 years on species Male/Female Differences The female has a much shorter and stubbier tale, while the male’s tail is elongated. Compatibility Milk Snakes are best kept singly. Many Milk Snake species favor other snakes as food and are notorious cannibals. Origin Subtropical lowland areas of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. Climate Tropical. Day Cycle Primarily nocturnal. Temperature The hot end of the enclosure should be 86-90°F while the cool end should be approximately 76-80°F. During the night, the temperature should drop to a more constant overall temperature of 74-78°F. Lighting Supplemental lighting is not necessary for Milk Snakes. Full spectrum lighting however increases appetite and emotional health if used on a 12/12 cycle, meaning 12 hours on and 12 hours off. Continuous bright, overhead lighting is stressful to snakes. Make sure to provide a basking spot if one plans on using UVB lighting. Humidity 50-70% humidity. Habitat/Territory Tropical lowlands. Extremely partial to shady areas and caves. Substrate/Bedding Some viable options for substrate include; sterilized bark, cage carpet, cypress mulch, or coconut husk. Keep damp moss in about 30% of your cage located on or near your snakes hiding spot. Cage should be sprayed down once or twice day to maintain proper humidity levels. Less porous substrate is least likely to develop mite infestations and will increases ease of cleaning. Hiding Place/Den Provide abundant plants - either artificial or real - as well as caves or hides on both ends of the tank. -

Pueblan Milk Snake Lampropeltis Triangulum

UPDATED 2019 Pueblan Milk Snake Lampropeltis triangulum Natural History Description: Milk snakes can grow to 20-60 inches in length. Milk snakes range from Canada to Ecuador, and their appearance, habitat, and diet can vary greatly throughout this distribution. Some, like CNC’s milk snake, have brightly colored stripes, but others are cream with brown or red blotches. The latter appearance is more common in the northern US, while brightly striped patterns are found in the southern US and down into Mexico and South America. While these snakes lack venom, they can easily be confused with a coral snake, which is venomous. In fact, the red-black-yellow pattern probably evolved to mimic the appearance of dangerous coral snakes. Vocalizations: If the milk snake feels threatened by a fox, coyote, or other danger, it will vibrate its tail in the nearby leaves or grass, making a sound similar to a rattlesnake. Breeding: Milk snakes are “oviparous,” which means they lay eggs. They mate in late spring or ear- ly summer and the female will lay 8-12 eggs. The young snakes are 6 to 10 inches long. Distribution: Milk snakes are found throughout northern Mexico. Habitat: The milk snake is able to thrive in a variety of habitats, including forests, grasslands, rocky outcroppings, and barns. They were given the name ‘milk snake’ because people falsely believed the snakes came to barns to steal milk from cows. Milk snakes like to live near barns primarily due to the abundance of prey there. They are elusive snakes and, in the warmer months, only come out at night to hunt. -

Evolution of a Snake Mimicry Complex

Evolution of a snake mimicry complex George Raymond Harper, Jr. A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Biology. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by: David W. Pfennig Joel G. Kingsolver Peter B. Marko Karin S. Pfennig Maria R. Servedio © 2006 George Raymond Harper Jr. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract George Harper : Evolution of a snake mimicry complex (Under the direction of David Pfennig) Batesian mimicry, the adaptive resemblance of harmless organisms (mimics) to harmful organisms (models) that causes predators to avoid both models and mimics, occurs in diverse taxa. Despite the fascination that mimicry complexes generate, many questions remain unanswered concerning the role of mimicry in evolution. My Ph.D. research has examined the evolution of a snake mimicry co mplex in the southeastern United States in which selection on the mimetic phenotype varies spatially in magnitude and direction. The mimic, harmless scarlet kingsnakes (Lampropeltis triangulum elapsoides ), and the model, venomous eastern coral snakes ( Micr urus fulvius ), vary in absolute and relative abundance such that the model is more common deep within its range and the mimic is more abundant at the edge of the model’s range. Also, despite selection against the mimetic phenotype outside the range of the model, the range of the mimic exceeds that of the model (an area termed allopatry). Therefore, I sought to determine: 1) what evolutionary mechanisms maintain the mimic in allopatry, 2) whether there has been an evolutionary response to selection against t he mimetic phenotype in allopatry, and 3) whether spatial variation in the relative abundance of models and mimics leads to spatial variation in the degree to which mimics resemble the local model.