Copperhead & Endangered Species Agkistrodon Contortrix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COTTONMOUTH Agkistrodon Piscivorus

COTTONMOUTH Agkistrodon piscivorus Agkistrodon is derived from ankistron and odon which in Greek mean “fishhook” and “tooth or teeth;” referring to the curved fangs of this species. Piscivorus is derived from piscis and voro which in Latin mean “fish” and “to eat”. Another common name for cottonmouth is water moccasin. The Cottonmouth is venomous. While its bite is rarely fatal, tissue damage is likely to occur and can be severe if not treated promptly. IDENTIFICATION Appearance: The cottonmouth is a stout- bodied venomous snake that reaches lengths of 30 to 42 inches as adults. Most adults are uniformly dark brown, olive, or black, tending to lose the cross banded patterning with age. Some individuals may have a dark cheek stripe (upper right image). The cottonmouth has the diagnostic features of the pit-viper family such as a wedge-shaped head, sensory pits between the eyes and nostrils, and vertical “cat-like” pupils. Juveniles are lighter and more boldly patterned with a yellow coloration toward the tip of the tail (lower right image). Dorsal scales are weakly keeled, and the subcaudal scales form only one row. Cottonmouths also have a single anal Mike Redmer plate. Subspecies: There are three subspecies of the cottonmouth. The Western Cottonmouth (A. p. leucostoma) is the only subspecies found in the Midwest. The term leucostoma refers to the white interior of mouth. Confusing Species: The non-venomous watersnakes (Nerodia) are commonly confused with Cottonmouths across their range, simply because they are snakes in water. Thus it is important to note that Cottonmouths are only found in southernmost Midwest. -

Nelsons Milk Snake

Nelsons Milk SNake PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION: • This species of milk snake typically keeps to southern and central Mexico, but have been • The red rings on a Nelson’s milk snake found on some tropical/costal islands as well. range from around 13 to 18, and has a predominantly black snout (except for DIET: when albino). • These snakes will consume various types • The red bands on the nelson’s milk snake are of rodents, amphibians, lizards and even the thickest stripes on their bodies, with black other snakes. being slightly thinner, and white being the thinnest. • Due to their cannibalistic nature nelson’s milk snakes must be housed separately SIZE AND LIFESPAN: when not breeding. • Adult nelson’s milk snakes are a small REPRODUCTION: to medium size snake, averaging around 42 inch (106cm). • Mating in the wild takes place in late spring and early summer. • The lifespan of these snakes is around 12-15 years, but has been known to live to 20 years • The female will select a nest site that is warm of age in captivity! and humid, and will then lays her clutch which contains up to 15 eggs. NATIVE HABITAT: • This species is often found in costal bushes and tropical forests, which provided them with many hiding spots that can protect them. • They are typically found in Mexico, ranging from southern Guanajuato and central Jalisco, all the way to the Pacific Coast. FUN FACTS: • The Nelson’s milk snake is a subspecies of king snakes. • They are nonvenomous, but are typically very shy and take a while to get use to being handled. -

Species Results from Database Search

Species Results From Database Search Category Reptiles Common Name Alabama Map Turtle Scientific Name Graptemys pulchra LCC Global Trust N No. of States 1 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Kingsnake Scientific Name Lampropeltis getula nigra LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Racer Scientific Name Coluber constrictor constrictor LCC Global Trust N No. of States 1 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Rat Snake Scientific Name Elaphe obsoleta LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Bog turtle Scientific Name Clemmys (Glyptemys) muhlen LCC Global Trust Y No. of States 4 Habitat_Feature Monday, January 28, 2013 Page 1 of 14 Category Reptiles Common Name Broadhead Skink Scientific Name Eumeces laticeps LCC Global Trust N No. of States 5 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Coal Skink Scientific Name Eumeces anthracinus LCC Global Trust Y No. of States 8 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Five-lined Skink Scientific Name Eumeces fasciatus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Map Turtle Scientific Name Graptemys geographica LCC Global Trust N No. of States 6 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Musk Turtle Scientific Name Sternotherus odoratus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Monday, January 28, 2013 Page 2 of 14 Category Reptiles Common Name Common Ribbonsnake Scientific Name Thamnophis sauritus sauritus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 6 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Snapping Turtle Scientific Name Chelydra serpentina LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Corn snake Scientific Name Elaphe guttata guttata LCC Global Trust N No. -

Venomous Snakes of Texas.Pub

Price, Andrew. 1998. Poisonous Snakes of Texas. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Distributed by University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas. Tenant, Alan. 1998. A Field Guide to Texas Snakes. Gulf Publishing Com- pany, Houston, Texas. Texas Coral Snake, Micrurus fulvius Werler, John E. & James R. Dixon. tenere. This species averages 20 2000. Texas Snakes: Identification, inches (record 47 inches). Slender, Distribution, and Natural History. Uni- brightly colored snake with red, black versity of Texas Press, Austin, Texas. and yellow bands that completely en- circle the body. Red and yellow color touch. Venomous Snakes of East Texas Additional, more in depth information Written by: Gordon B. Henley, Jr. Zoo on snakes of Texas, in particular the Director venomous species, can be found in Photos by: Celia K. Falzone, General the following publications: Curator Editorial Assistance provided by: Conant, Roger & Joseph T. Collins. J. Colin Crawford, Education Assistant 1998. A Field Guide to Reptile and Amphibians: Eastern and Central North America. Houghton Mifflin Provided as a Public Service Company, Boston, Massachusetts. by Dixon, James R. 1987. Amphibians and Reptiles of Texas. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, Texas. (2nd Edition 2000). Venomous Snakes of East Texas with Emphasis on Angelina County Texas provides habitat for approximately 115 species of snakes with nearly 44 spe- cies found in the piney woods region of East Texas. Fifteen species of venomous snakes are found throughout the state while only 5 venomous species are found Southern Copperhead, Agkistrodon in the East Texas pine forests: two spe- contortrix contortrix. This species aver- cies of rattlesnakes; a copperhead; the ages 24 inches (record 52 inches). -

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S: A Reference to Snake Identification, Field Safety, Basic Safe Capture and Handling Methods and First Aid Measures for Reptile Envenomation Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, William M. Niederhofer ACO & John Wisser MS. Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 (Wozniak) City Of Pearland Animal Control, 2002 Old Alvin Rd. Pearland, Texas 77581 (Niederhofer) 464 County Road 949 E Alvin, Texas 77511 (Wisser) Corresponding Author: Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 [email protected] ABSTRACT: Each year numerous emergency response personnel including animal control officers, police officers, wildlife rehabilitators, public health officers and others either respond to calls involving venomous snakes or are forced to venture into the haunts of these animals in the scope of their regular duties. North America is home to two distinct families of native venomous snakes: Viperidae (rattlesnakes, copperheads and cottonmouths) and Elapidae (coral snakes) and southeastern Texas has indigenous species representing both groups. While some of these snakes are easily identified, some are not and many rank amongst the most feared and misunderstood animals on earth. This article specifically addresses all of the native species of venomous snakes that inhabit Health Service Region 6/5s and is intended to serve as a reference to snake identification, field safety, basic safe capture and handling methods and the currently recommended first aide measures for reptile envenomation. -

Lizards & Snakes: Alive!

LIZARDSLIZARDS && SNAKES:SNAKES: ALIVE!ALIVE! EDUCATOR’SEDUCATOR’S GUIDEGUIDE www.sdnhm.org/exhibits/lizardsandsnakeswww.sdnhm.org/exhibits/lizardsandsnakes Inside: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Must-Read Key Concepts and Background Information • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Activities to Extend Learning Back in the Classroom • Map of the Exhibition to Guide Your Visit • Correlations to California State Standards Special thanks to the Ellen Browning Scripps Foundation and the Nordson Corporation Foundation for providing underwriting support of the Teacher’s Guide KEYKEY CONCEPTSCONCEPTS Squamates—legged and legless lizards, including snakes—are among the most successful vertebrates on Earth. Found everywhere but the coldest and highest places on the planet, 8,000 species make squamates more diverse than mammals. Remarkable adaptations in behavior, shape, movement, and feeding contribute to the success of this huge and ancient group. BEHAVIOR Over 45O species of snakes (yet only two species of lizards) An animal’s ability to sense and respond to its environment is are considered to be dangerously venomous. Snake venom is a crucial for survival. Some squamates, like iguanas, rely heavily poisonous “soup” of enzymes with harmful effects—including on vision to locate food, and use their pliable tongues to grab nervous system failure and tissue damage—that subdue prey. it. Other squamates, like snakes, evolved effective chemore- The venom also begins to break down the prey from the inside ception and use their smooth hard tongues to transfer before the snake starts to eat it. Venom is delivered through a molecular clues from the environment to sensory organs in wide array of teeth. -

Eastern Milksnake,Lampropeltis Triangulum

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2014 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2014. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 61 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 29 pp. Fischer, L. 2002. COSEWIC status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-29 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Jonathan Choquette for writing the status report on the Eastern Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum) in Canada. This report was prepared under contract with Environment Canada and was overseen by Jim Bogart, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Amphibians and Reptiles Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Couleuvre tachetée (Lampropeltis triangulum) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Eastern Milksnake — Sketch of the Eastern Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum). -

Checklist of Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York

CHECKLIST OF AMPHIBIANS, REPTILES, BIRDS AND MAMMALS OF NEW YORK STATE Including Their Legal Status Eastern Milk Snake Moose Blue-spotted Salamander Common Loon New York State Artwork by Jean Gawalt Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Page 1 of 30 February 2019 New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Diversity Group 625 Broadway Albany, New York 12233-4754 This web version is based upon an original hard copy version of Checklist of the Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York, Including Their Protective Status which was first published in 1985 and revised and reprinted in 1987. This version has had substantial revision in content and form. First printing - 1985 Second printing (rev.) - 1987 Third revision - 2001 Fourth revision - 2003 Fifth revision - 2005 Sixth revision - December 2005 Seventh revision - November 2006 Eighth revision - September 2007 Ninth revision - April 2010 Tenth revision – February 2019 Page 2 of 30 Introduction The following list of amphibians (34 species), reptiles (38), birds (474) and mammals (93) indicates those vertebrate species believed to be part of the fauna of New York and the present legal status of these species in New York State. Common and scientific nomenclature is as according to: Crother (2008) for amphibians and reptiles; the American Ornithologists' Union (1983 and 2009) for birds; and Wilson and Reeder (2005) for mammals. Expected occurrence in New York State is based on: Conant and Collins (1991) for amphibians and reptiles; Levine (1998) and the New York State Ornithological Association (2009) for birds; and New York State Museum records for terrestrial mammals. -

Climate Change and Evolution of the New World Pitviper Genus

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2009) 36, 1164–1180 ORIGINAL Climate change and evolution of the New ARTICLE World pitviper genus Agkistrodon (Viperidae) Michael E. Douglas1*, Marlis R. Douglas1, Gordon W. Schuett2 and Louis W. Porras3 1Illinois Natural History Survey, Institute for ABSTRACT Natural Resource Sustainability, University of Aim We derived phylogenies, phylogeographies, and population demographies Illinois, Champaign, IL, 2Department of Biology and Center for Behavioral for two North American pitvipers, Agkistrodon contortrix (Linnaeus, 1766) and Neuroscience, Georgia State University, A. piscivorus (Lace´pe`de, 1789) (Viperidae: Crotalinae), as a mechanism to Atlanta, GA and 37705 Wyatt Earp Avenue, evaluate the impact of rapid climatic change on these taxa. Eagle Mountain, UT, USA Location Midwestern and eastern North America. Methods We reconstructed maximum parsimony (MP) and maximum likelihood (ML) relationships based on 846 base pairs of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) ATPase 8 and ATPase 6 genes sequenced over 178 individuals. We quantified range expansions, demographic histories, divergence dates and potential size differences among clades since their last period of rapid expansion. We used the Shimodaira–Hasegawa (SH) test to compare our ML tree against three biogeographical hypotheses. Results A significant SH test supported diversification of A. contortrix from northeastern Mexico into midwestern–eastern North America, where its trajectory was sundered by two vicariant events. The first (c. 5.1 Ma) segregated clades at 3.1% sequence divergence (SD) along a continental east–west moisture gradient. The second (c. 1.4 Ma) segregated clades at 2.4% SD along the Mississippi River, coincident with the formation of the modern Ohio River as a major meltwater tributary. -

AG-472-02 Snakes

Snakes Contents Intro ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................1 What are Snakes? ...............................................................1 Biology of Snakes ...............................................................1 Why are Snakes Important? ............................................1 People and Snakes ............................................................3 Where are Snakes? ............................................................1 Managing Snakes ...............................................................3 Family Colubridae ...............................................................................................................................................................................................5 Eastern Worm Snake—Harmless .................................5 Red-Bellied Water Snake—Harmless ....................... 11 Scarlet Snake—Harmless ................................................5 Banded Water Snake—Harmless ............................... 11 Black Racer—Harmless ....................................................5 Northern Water Snake—Harmless ............................12 Ring-Necked Snake—Harmless ....................................6 Brown Water Snake—Harmless .................................12 Mud Snake—Harmless ....................................................6 Rough Green Snake—Harmless .................................12 -

Snakes of New York State

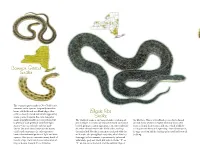

Common Garter Snake ˜e common garter snake is New York’s most common snake species, frequently found in lawns, old ÿelds and woodland edges. One Black Rat of three closely related and similar appearing snake species found in the state, the garter Snake snake is highly variable in color pattern, but ˜e black rat snake is our longest snake, reaching six the blotches. ˜is is a woodland species, but is found is generally dark greenish with three light feet in length. Its scales are uniformly black and faintly around barns where it is highly desirable for its abil- stripes—one on each side and one mid- keeled, giving it a satiny appearance. In some individu- ity to seek and destroy mice and rats, which it kills by dorsal. ˜e mid-dorsal stripe can be barely als, white shows between the black scales, making coiling around them and squeezing. Around farmyards, visible and sometimes the sides appear to the snake look blotchy. Sometimes confused with the its eggs are o˛en laid in shavings piles used for livestock have a checkerboard pattern of light and dark milk snake, the young black rat snake, which hatches bedding. squares. ˜is species consumes many kinds of from eggs in late summer, is prominently patterned insects, slugs, worms and an occasional small with white, grey and black, but lacks both the “Y” or frog or mouse. Length: 16 to 30 inches. “V” on the top of the head, and the reddish tinge to Timber Rattlesnake Copperhead ˜e copperhead is an attractively-patterned, venomous snake with a pinkish-tan color super- imposed on darker brown to chestnut colored saddles that are narrow at the spine and wide at the sides. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L.