Snakes of Missouri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressure and Duration of Constriction in Boa Constrictor Is Influenced by a Simulated Prey Heartbeat Allison Elizabeth Hall Dickinson College

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Student Honors Theses By Year Student Honors Theses 5-23-2010 Pressure and Duration of Constriction in Boa Constrictor is Influenced by a Simulated Prey Heartbeat Allison Elizabeth Hall Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_honors Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Allison Elizabeth, "Pressure and Duration of Constriction in Boa Constrictor is Influenced by a Simulated Prey Heartbeat" (2010). Dickinson College Honors Theses. Paper 86. This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pressure and Duration of Constriction in Boa constrictor is Influenced by a Simulated Prey Heartbeat By Allison E. Hall With the collaboration of Amanda Hayes and Katelyn McCann Submitted in partial fulfillment of Honors Requirements for the Department of Biology Dr. Scott Boback, Supervisor Dr. Charles Zwemer, Supervisor Dr. David Kushner, Reader May 18, 2010 Abstract Constricting prey is energetically costly for snakes and therefore it would be beneficial to minimize this cost. However, the consequences of arresting a constriction event too soon could be deadly. Thus, the duration of constriction is bounded by competing demands to kill prey and conserve energy. Snakes possess mechanoreceptors within their ventral and dorsal skin that are used for detecting approaching predators and prey. This experiment sought to determine whether Boas (Boa constrictor) can sense a simulated heartbeat in their prey. It was predicted that if snakes possess this ability, those constricting rats with a simulated heart would constrict with greater pressure and increased duration than snakes constricting rats without a simulated heartbeat. -

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Kansas Biological Survey Report #151 Kelly Kindscher, Randy Jennings, William Norris, and Roland Shook September 8, 2008 Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Cover Photo: The Gila River in New Mexico. Photo by Kelly Kindscher, September 2006. Kelly Kindscher, Associate Scientist, Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, 2101 Constant Avenue, Lawrence, KS 66047, Email: [email protected] Randy Jennings, Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] William Norris, Associate Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Roland Shook, Emeritus Professor, Biology, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Citation: Kindscher, K., R. Jennings, W. Norris, and R. Shook. Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico. Open-File Report No. 151. Kansas Biological Survey, Lawrence, KS. ii + 42 pp. Abstract During 2006 and 2007 our research crews collected data on plants, vegetation, birds, reptiles, and amphibians at 49 sites along the Gila River in southwest New Mexico from upstream of the Gila Cliff Dwellings on the Middle and West Forks of the Gila to sites below the town of Red Rock, New Mexico. -

Pituophis Catenifer

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer Pacific Northwestern Gophersnake – P.c. catenifer Great Basin Gophersnake – P.C. deserticola Bullsnake – P.C. sayi in Canada EXTIRPATED - Pacific Northwestern Gophersnake – P.c. catenifer THREATENED - Great Basin Gophersnake – P.c. deserticola DATA DEFICIENT - Bullsnake – P.c. sayi 2002 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION DES ENDANGERED WILDLIFE IN ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: Please note: Persons wishing to cite data in the report should refer to the report (and cite the author(s)); persons wishing to cite the COSEWIC status will refer to the assessment (and cite COSEWIC). A production note will be provided if additional information on the status report history is required. COSEWIC 2002. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 33 pp. Waye, H., and C. Shewchuk. 2002. COSEWIC status report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer in Canada in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-33 pp. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Ếgalement disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport du COSEPAC sur la situation de la couleuvre à nez mince (Pituophis catenifer) au Canada Cover illustration: Gophersnake — Illustration by Sarah Ingwersen, Aurora, Ontario. -

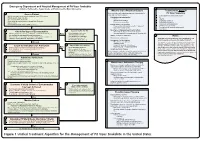

Snake Bite Protocol

Lavonas et al. BMC Emergency Medicine 2011, 11:2 Page 4 of 15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-227X/11/2 and other Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center treatment of patients bitten by coral snakes (family Ela- staff. The antivenom manufacturer provided funding pidae), nor by snakes that are not indigenous to the US. support. Sponsor representatives were not present dur- At the time this algorithm was developed, the only ing the webinar or panel discussions. Sponsor represen- antivenom commercially available for the treatment of tatives reviewed the final manuscript before publication pit viper envenomation in the US is Crotalidae Polyva- ® for the sole purpose of identifying proprietary informa- lent Immune Fab (ovine) (CroFab , Protherics, Nash- tion. No modifications of the manuscript were requested ville, TN). All treatment recommendations and dosing by the manufacturer. apply to this antivenom. This algorithm does not con- sider treatment with whole IgG antivenom (Antivenin Results (Crotalidae) Polyvalent, equine origin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Final unified treatment algorithm Marietta, Pennsylvania, USA)), because production of The unified treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1. that antivenom has been discontinued and all extant The final version was endorsed unanimously. Specific lots have expired. This antivenom also does not consider considerations endorsed by the panelists are as follows: treatment with other antivenom products under devel- opment. Because the panel members are all hospital- Role of the unified treatment algorithm -

Caryospora Duszynskii

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 65 Article 27 2011 Caryospora duszynskii (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from the Speckled Kingsnake, Lampropeltis holbrooki (Reptilia: Ophidia), in Arkansas, with a Summary of PreviousReports Chris T. McAllister Eastern Oklahoma State College, [email protected] H. W. Robison Southern Arkansas University R. S. Seville University of Wyoming Z. P. Roehrs University of Wyoming S. E. Trauth Arkansas State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation McAllister, Chris T.; Robison, H. W.; Seville, R. S.; Roehrs, Z. P.; and Trauth, S. E. (2011) "Caryospora duszynskii (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from the Speckled Kingsnake, Lampropeltis holbrooki (Reptilia: Ophidia), in Arkansas, with a Summary of PreviousReports," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 65 , Article 27. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol65/iss1/27 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This General Note is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 65 [2011], Art. 27 Caryospora duszynskii (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from the Speckled Kingsnake, Lampropeltis holbrooki (Reptilia: Ophidia), in Arkansas, with a Summary of Previous Reports C.T. -

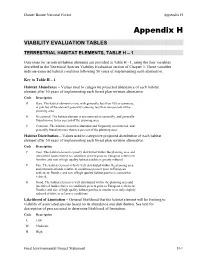

Appendices to the Final Environmental Impact Statement

Daniel Boone National Forest Appendix H Appendix H VIABILITY EVALUATION TABLES TERRESTRIAL HABITAT ELEMENTS, TABLE H – 1 Outcomes for terrestrial habitat elements are provided in Table H - 1, using the four variables described in the Terrestrial Species Viability Evaluation section of Chapter 3. These variables indicate expected habitat condition following 50 years of implementing each alternative. Key to Table H – 1 Habitat Abundance – Values used to categorize projected abundance of each habitat element after 50 years of implementing each forest plan revision alternative. Code Description R Rare. The habitat element is rare, with generally less than 100 occurrences, or patches of the element generally covering less than one percent of the planning area. O Occasional. The habitat element is encountered occasionally, and generally found on one to ten percent of the planning area. C Common. The habitat element is abundant and frequently encountered, and generally found on more than ten percent of the planning area. Habitat Distribution – Values used to categorize projected distribution of each habitat element after 50 years of implementing each forest plan revision alternative. Code Description P Poor. The habitat element is poorly distributed within the planning area and intermixed lands relative to conditions present prior to European settlement. Number and size of high quality habitat patches is greatly reduced. F Fair. The habitat element is fairly well distributed within the planning area and intermixed lands relative to conditions present prior to European settlement. Number and size of high quality habitat patches is somewhat reduced. G Good. The habitat element is well distributed within the planning area and intermixed lands relative to conditions present prior to European settlement. -

For Creative Minds

For Creative Minds The For Creative Minds educational section may be photocopied or printed from our website by the owner of this book for educational, non-commercial uses. Cross-curricular teaching activities, interactive quizzes, and more are available online. Go to www.ArbordalePublishing.com and click on the book’s cover to explore all the links. Diurnal or Nocturnal Animals that are active during the day and asleep at night are diurnal. Animals that are active at night and asleep during the day are nocturnal. Read the following sentences and look for clues to determine if the animal is diurnal or nocturnal. A large dog sneaks up on The garter snake passes the skunk in the dark of the morning hunting night. The skunk stamps and basking in the warm her feet and throws her sunlight. If a predator tail up in the air. She arrives, he will hide his gives the other animal a head under some leaves warning before spraying. and flail his tail until it goes away. This bluebird is a The bright afternoon sun helpful garden bird. He helps this high-flying spends his days eating red-tailed hawk search insects off the plants and for her next meal. She defending his territory can see a grasshopper from other birds. from more than 200 feet (61m) away! As night falls, a small, The barn owl sweeps flying beetle with a over the field under glowing abdomen the dark night sky. emerges. She flashes her He flies slowly and light to signal to other silently, scanning the fireflies to come out. -

Amphibians Present in the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve

Amphibians present in the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. The species list was generated from data compiled from NPS observations and during a 2001-2002 reptile and amphibian inventory conducted by Noah J. Anderson and Dr. Richard A. Seigel, Southeastern Louisiana University, Hammond, Louisiana. Common Name Scientific Name Habitat Association Smallmouth salamander Ambystoma texanum hardwood forests Three-toed amphiuma Amphiuma tridactylum swamp, marsh, restricted to aquatic habitats in hardwood forests Dwarf salamander Eurycea quadridigitata hardwood forests, marsh Eastern newt Notophthalmus viridescens found in and near aquatic habitats Southern dusky salamander Desmognathus auriculatus hardwood forests Lesser siren Siren intermedia swamp, marsh Northern cricket frog Acris crepitans all habitats Gulf coast toad Bufo valliceps all habitats Greenhouse frog Eleutherodactylus planirostris hardwood forests Eastern narrowmouth toad Gastrophryne carolinensis all habitats Bird-voiced treefrog Hyla avivoca hardwood forests, swamp Green treefrog Hyla cinerea all habitats Squirrel treefrog Hyla squirella swamp, hardwood forests Spring peeper Pseudacris crucifer swamp, hardwood forests Chorus frog Pseudacris triseriata hardwood forests, swamp Bullfrog Rana catesbeiana hardwood forests, swamp Bronze frog Rana clamitans all habitats Pig frog Rana grylio marsh Southern leopard frog Rana sphenocephala swamp, marsh Reptiles present in the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. -

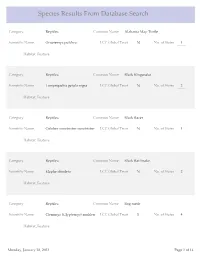

Species Results from Database Search

Species Results From Database Search Category Reptiles Common Name Alabama Map Turtle Scientific Name Graptemys pulchra LCC Global Trust N No. of States 1 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Kingsnake Scientific Name Lampropeltis getula nigra LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Racer Scientific Name Coluber constrictor constrictor LCC Global Trust N No. of States 1 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Rat Snake Scientific Name Elaphe obsoleta LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Bog turtle Scientific Name Clemmys (Glyptemys) muhlen LCC Global Trust Y No. of States 4 Habitat_Feature Monday, January 28, 2013 Page 1 of 14 Category Reptiles Common Name Broadhead Skink Scientific Name Eumeces laticeps LCC Global Trust N No. of States 5 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Coal Skink Scientific Name Eumeces anthracinus LCC Global Trust Y No. of States 8 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Five-lined Skink Scientific Name Eumeces fasciatus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Map Turtle Scientific Name Graptemys geographica LCC Global Trust N No. of States 6 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Musk Turtle Scientific Name Sternotherus odoratus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Monday, January 28, 2013 Page 2 of 14 Category Reptiles Common Name Common Ribbonsnake Scientific Name Thamnophis sauritus sauritus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 6 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Snapping Turtle Scientific Name Chelydra serpentina LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Corn snake Scientific Name Elaphe guttata guttata LCC Global Trust N No. -

The Herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: a Bibliography

The Herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: A Bibliography Revised 2 nd Edition Brian S. Gray and Mark Lethaby Special Publication of the Natural History Museum at the Tom Ridge Environmental Center, Number 1 2 Special Publication of the Natural History Museum at the Tom Ridge Environmental Center The Herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: A Bibliography Revised 2 nd Edition Compiled by Brian S. Gray [email protected] and Mark Lethaby Natural History Museum at the Tom Ridge Environmental Center, 301 Peninsula Dr., Suite 3, Erie, PA 16505 [email protected] Number 1 Erie, Pennsylvania 2017 Cover image: Smooth Greensnake, Opheodrys vernalis from Erie County, Pennsylvania. 3 Introduction Since the first edition of The herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: a bibliography (Gray and Lethaby 2012), numerous articles and books have been published that are pertinent to the literature of the region’s amphibians and reptiles. The purpose of this revision is to provide a comprehensive and updated list of publications for use by researchers interested in Erie County’s herpetofauna. We have made every effort to include all major works on the herpetology of Erie County. Included are the works of Atkinson (1901) and Surface (1906; 1908; 1913) which are among the earliest to note amphibians and or reptiles specifically from sites in Erie County, Pennsylvania. The earliest publication to utilize an Erie County specimen, however, may have been that of LeSueur (1817) in his description of Graptemys geographica (Lindeman 2009). While the bibliography is quite extensive, we did not attempt to list everything, such as articles in local newspapers, and unpublished reports, although some of the more significant of these are included. -

Wildlife Spotting Along the Thames

WILDLIFE SPOTTING ALONG THE THAMES Wildlife along the Thames is plentiful, making it a great location for birding. Bald Eagles and Osprey are regularly seen nesting and feeding along the river. Many larger birds utilize the Thames for habitat and feeding, including Red Tailed Hawks, Red Shoulder Hawks, Kestrels, King Fishers, Turkey Vultures, Wild Turkeys, Canada Geese, Blue Herons, Mallard Ducks, Black and Wood Ducks. Several species of owl have also been recorded in, such as the Barred Owl, Barn Owl, Great Horned Owl and even the Snowy Owl. Large migratory birds such as Cormorants, Tundra Swans, Great Egret, Common Merganser and Common Loon move through the watershed during spring and fall. The Thames watershed also contains one of Canada’s most diverse fish communities. Over 90 fish species have been recorded (more than half of Ontario’s fish species). Sport fishing is popular throughout the watershed, with popular species being: Rock Bass, Smallmouth Bass, Largemouth Bass, Walleye, Yellow Perch, White Perch, Crappie, Sunfish, Northern Pike, Grass Pickerel, Muskellunge, Longnose Gar, Salmon, Brown Trout, Brook Trout, Rainbow Trout, Channel Catfish, Barbot and Redhorse Sucker. Many mammals utilize the Thames River and the surrounding environment. White-tailed Deer, Muskrat, Beaver, Rabbit, Weasel, Groundhog, Chipmunk, Possum, Grey Squirrel, Flying Squirrel, Little Brown Bats, Raccoon, Coyote, Red Fox and - although very rare - Cougar and Black Bear have been recorded. Reptiles and amphibians in the watershed include Newts and Sinks, Garter Snake, Ribbon Snake, Foxsnake, Rat Snake, Spotted Turtle, Map Turtle, Painted Turtle, Snapping Turtle and Spiny Softshell Turtle. Some of the wildlife species found along the Thames are endangered making it vital to respect and not disrupt their sensitive habitat areas. -

Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L

CIR1462 Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L. Casler, Elise V. Pearlstine, Frank J. Mazzotti, and Kenneth L. Krysko2 Background snakes are often escapees or are released deliberately and illegally by owners who can no longer care for them. Snakes are members of the vertebrate order Squamata However, there has been no documentation of these snakes (suborder Serpentes) and are most closely related to lizards breeding in the EAA (Tennant 1997). (suborder Sauria). All snakes are legless and have elongated trunks. They can be found in a variety of habitats and are able to climb trees; swim through streams, lakes, or oceans; Benefits of Snakes and move across sand or through leaf litter in a forest. Snakes are an important part of the environment and play Often secretive, they rely on scent rather than vision for a role in keeping the balance of nature. They aid in the social and predatory behaviors. A snake’s skull is highly control of rodents and invertebrates. Also, some snakes modified and has a great degree of flexibility, called cranial prey on other snakes. The Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis kinesis, that allows it to swallow prey much larger than its getula floridana), for example, prefers snakes as prey and head. will even eat venomous species. Snakes also provide a food source for other animals such as birds and alligators. Of the 45 snake species (70 subspecies) that occur through- out Florida, 23 may be found in the Everglades Agricultural Snake Conservation Area (EAA). Of the 23, only four are venomous. The venomous species that may occur in the EAA are the coral Loss of habitat is the most significant problem facing many snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius), Florida cottonmouth wildlife species in Florida, snakes included.