Systematics of the Colubrid Snake Lamproneltis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

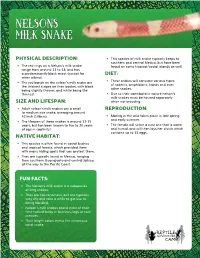

Nelsons Milk Snake

Nelsons Milk SNake PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION: • This species of milk snake typically keeps to southern and central Mexico, but have been • The red rings on a Nelson’s milk snake found on some tropical/costal islands as well. range from around 13 to 18, and has a predominantly black snout (except for DIET: when albino). • These snakes will consume various types • The red bands on the nelson’s milk snake are of rodents, amphibians, lizards and even the thickest stripes on their bodies, with black other snakes. being slightly thinner, and white being the thinnest. • Due to their cannibalistic nature nelson’s milk snakes must be housed separately SIZE AND LIFESPAN: when not breeding. • Adult nelson’s milk snakes are a small REPRODUCTION: to medium size snake, averaging around 42 inch (106cm). • Mating in the wild takes place in late spring and early summer. • The lifespan of these snakes is around 12-15 years, but has been known to live to 20 years • The female will select a nest site that is warm of age in captivity! and humid, and will then lays her clutch which contains up to 15 eggs. NATIVE HABITAT: • This species is often found in costal bushes and tropical forests, which provided them with many hiding spots that can protect them. • They are typically found in Mexico, ranging from southern Guanajuato and central Jalisco, all the way to the Pacific Coast. FUN FACTS: • The Nelson’s milk snake is a subspecies of king snakes. • They are nonvenomous, but are typically very shy and take a while to get use to being handled. -

Griffith Park Wildlife Management Plan

GRIFFITH PARK WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT PLAN (FINAL) January 22, 2009 Monterey ensatina Ensatina eschsholtzi, photographed in Brush Canyon in August 2008 (D.S. Cooper) Report submitted to the Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks by Cooper Ecological Monitoring, Inc. Contract No. 2930. Daniel S. Cooper and Paul Mathewson Cooper Ecological Monitoring, Inc. 5850 W. 3rd St., #167 Los Angeles, CA 90036 www.cooperecological.com Contact: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 4 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (incl. Best Management Practices) . 4 3. INTRODUCTION . 7 3.1. Justification for Plan . 7 3.2 Audience . 8 3.3 History . 9 3.4 Setting . 10 3.5 Wildlife Management Plan Goals and Guiding Principles . 11 4. HABITAT DESCRIPTIONS . 12 4.1 Terrestrial Habitats . 15 4.2 Aquatic Habitats . 22 4.3 Urban Interface Zone . 23 5. SPECIES INFORMATION . 24 5.1 Special-status species . 25 5.2 Stewardship species . 34 6. WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT GOALS . 41 6.1 Promote native wildlife populations and habitats . 41 6.1.1 Identify and defend native vegetation and biological "hotspots" . 41 6.1.2 Clarify location and usage of wildlife corridors . 42 6.1.3 Identify restoration priorities (incl. site descriptions) . 44 6.2 Facilitate the collection of wildlife distribution and ecological information . 51 6.3 Minimize human-wildlife conflict . 52 2 6.3.1 Strengthen law enforcement . 52 6.3.2 Consult with regulatory agencies . 52 6.3.3 Reduce "edge effects" . 54 6.3.4 Manage recreation to avoid conflicts with wildlife . 56 6.3.5 Reduce "passive wildlife feeding" . 58 6.3.6 Reduce use of rodenticides near wildland habitat . -

Non-Native Small Terrestrial Vertebrates in the Galapagos 2 3 Diego F

1 Non-Native Small Terrestrial Vertebrates in the Galapagos 2 3 Diego F. Cisneros-Heredia 4 5 Universidad San Francisco de Quito USFQ, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, Laboratorio de Zoología 6 Terrestre & Museo de Zoología, Quito 170901, Ecuador 7 8 King’s College London, Department of Geography, London, UK 9 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 12 13 14 Introduction 15 Movement of propagules of a species from its current range to a new area—i.e., extra-range 16 dispersal—is a natural process that has been fundamental to the development of biogeographic 17 patterns throughout Earth’s history (Wilson et al. 2009). Individuals moving to new areas usually 18 confront a different set of biotic and abiotic variables, and most dispersed individuals do not 19 survive. However, if they are capable of surviving and adapting to the new conditions, they may 20 establish self-sufficient populations, colonise the new areas, and even spread into nearby 21 locations (Mack et al. 2000). In doing so, they will produce ecological transformations in the 22 new areas, which may lead to changes in other species’ populations and communities, speciation 23 and the formation of new ecosystems (Wilson et al. 2009). 24 25 Human extra-range dispersals since the Pleistocene have produced important distribution 26 changes across species of all taxonomic groups. Along our prehistory and history, we have aided 27 other species’ extra-range dispersals either by deliberate translocations or by ecological 28 facilitation due to habitat changes or modification of ecological relationships (Boivin et al. 29 2016). -

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S: A Reference to Snake Identification, Field Safety, Basic Safe Capture and Handling Methods and First Aid Measures for Reptile Envenomation Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, William M. Niederhofer ACO & John Wisser MS. Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 (Wozniak) City Of Pearland Animal Control, 2002 Old Alvin Rd. Pearland, Texas 77581 (Niederhofer) 464 County Road 949 E Alvin, Texas 77511 (Wisser) Corresponding Author: Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 [email protected] ABSTRACT: Each year numerous emergency response personnel including animal control officers, police officers, wildlife rehabilitators, public health officers and others either respond to calls involving venomous snakes or are forced to venture into the haunts of these animals in the scope of their regular duties. North America is home to two distinct families of native venomous snakes: Viperidae (rattlesnakes, copperheads and cottonmouths) and Elapidae (coral snakes) and southeastern Texas has indigenous species representing both groups. While some of these snakes are easily identified, some are not and many rank amongst the most feared and misunderstood animals on earth. This article specifically addresses all of the native species of venomous snakes that inhabit Health Service Region 6/5s and is intended to serve as a reference to snake identification, field safety, basic safe capture and handling methods and the currently recommended first aide measures for reptile envenomation. -

Snakes of Utah by Douglas C. Cox and Wilmer W. Tanner

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 56 Number 3 Article 16 7-26-1996 Snakes of Utah by Douglas C. Cox and Wilmer W. Tanner Andrew H. Barnum Dixie College, St. George, Utah Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Barnum, Andrew H. (1996) "Snakes of Utah by Douglas C. Cox and Wilmer W. Tanner," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 56 : No. 3 , Article 16. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol56/iss3/16 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Great Basin Naturalist 56(3), © 1996, pp. 283-285 BOOK REVIEW Snakes of Utah. Douglas C. Cox aud Wilmer would be more useful if a caption were shown W. Tanner; Mark Philbrick, photography. by the other photographs throughout the text, Monte L. Beau Life Science Museum, Brig e.g., the photo opposite page 1 aud those shown ham Young University, Provo, UT. 1996. on pages 3, 4, 5, 8. The herpetologist will $17.95 softcover. probably recognize these without caption, but, as stated, it's likely these specialists will not be Snakes of Utah, anticipated for some time, the primary users of the text. Identification of is finally available for distribution. This book snakes by these photographs may not be obvi let (92 total pages) includes all known species ous to most readers. -

Lizards & Snakes: Alive!

LIZARDSLIZARDS && SNAKES:SNAKES: ALIVE!ALIVE! EDUCATOR’SEDUCATOR’S GUIDEGUIDE www.sdnhm.org/exhibits/lizardsandsnakeswww.sdnhm.org/exhibits/lizardsandsnakes Inside: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Must-Read Key Concepts and Background Information • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Activities to Extend Learning Back in the Classroom • Map of the Exhibition to Guide Your Visit • Correlations to California State Standards Special thanks to the Ellen Browning Scripps Foundation and the Nordson Corporation Foundation for providing underwriting support of the Teacher’s Guide KEYKEY CONCEPTSCONCEPTS Squamates—legged and legless lizards, including snakes—are among the most successful vertebrates on Earth. Found everywhere but the coldest and highest places on the planet, 8,000 species make squamates more diverse than mammals. Remarkable adaptations in behavior, shape, movement, and feeding contribute to the success of this huge and ancient group. BEHAVIOR Over 45O species of snakes (yet only two species of lizards) An animal’s ability to sense and respond to its environment is are considered to be dangerously venomous. Snake venom is a crucial for survival. Some squamates, like iguanas, rely heavily poisonous “soup” of enzymes with harmful effects—including on vision to locate food, and use their pliable tongues to grab nervous system failure and tissue damage—that subdue prey. it. Other squamates, like snakes, evolved effective chemore- The venom also begins to break down the prey from the inside ception and use their smooth hard tongues to transfer before the snake starts to eat it. Venom is delivered through a molecular clues from the environment to sensory organs in wide array of teeth. -

Israel's System for Risk Assessment of Imported Wildlife for the Pet Trade

Israel ’s System for Risk Assessment of Imported Wildlife for the Pet Trade Dr. Simon Nemtzov Israel Nature and Parks Authority Jerusalem, Israel [email protected] 1 Univ. Notre Dame – April 2008 Israel is especially susceptible to invasive species because of its rich diversity of habitats and ecosystems. Why does Israel have such a high level of biodiversity? Species per m 2 in Mediterranean countries Eurostat 2008 2 1 EUROPE ASIA AFRICA 3 Biogeography of Israel Northern Israel: – Mediterranean ecosystem – Up to 1000 mm rainfall Central Israel Iraq – Dense urban population Israel Southern Israel: – Sudanese desert ecosystem – < 100 mm rainfall – Relatively low human impact Saudi Arabia 40 miles / 60 km 4 2 Israel ’s geographic factors Small area: ~21,700 km 2 (~ 8,400 sq mi) – (about the size of New Jersey) Intersection of 3 continents: – Asia, Africa and Europe – 4 biogeographical regions: Rich diversity of ecotones and biota Sea of Galilee - Lake Kinneret 5 Wildlife biodiversity in Israel 16 species of Carnivores: Striped hyena (Hyena hyena ) 5 species of canids: wolf (Canis lupus ), 3 foxes, golden jackal (C. aureus ) 5 sp. of mustelids : 2 badgers, beech marten, marbled polecat, otter (Lutra lutra ) Egyptian mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon ) 4 species of felids 6 3 Wildlife biodiversity in Israel 4 species of felids: Caracal (Felis caracal ) Leopard (Panthera pardus ) Wild cat (Felis silvestris ) Jungle cat (Felis chaus ) (Sand cat (Felis margarita) ) 7 Risk Assessment Procedure Simplified system based on Australia ’s system (Bomford 1991, 2003) Importer requests an import permit from INPA No application fee! INPA ecologist collects biological data (answers “The Questions ”), prepares opinion, and assigns initial risk category (H / M / L) 3 ecologist referees → Consensus category Coypu 8 4 The risk assessment questions 1. -

3.7 Biological Resources

3.7 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This section identifies major plant and animal resources within the City’s Planning Area and assesses the potential impacts of the proposed General Plan on biological resources with the understanding that certain resources, especially wildlife, are transitory and may potentially be present in a wide variety of areas regardless of previous records of observation. The City’s Planning Area consists of its incorporated boundaries and adopted Sphere of Influence (SOI). The County’s Planning Area consists of unincorporated land within the One Valley One Vision (OVOV) Planning Area boundaries that is located outside the City’s boundaries and the adopted SOI. The City and the County Planning Areas together comprise the OVOV Planning Area. A substantial portion of the area within the City has been developed. Species within the remaining natural areas are adapted to the Mediterranean climate of the region, in that they thrive in the cool, wet winters, and dry, hot summers typical of the area. Within the City boundaries, these areas include the Santa Clara River through the City; and portions of San Francisquito Canyon, Sand Canyon, Whitney Canyon, and Placerita Canyon. The major natural features of the City’s adopted SOI include the Liebre Mountains south of the National Forest boundary, including Cruzan Mesa and portions of Tick Canyon, Mint Canyon, Bouquet Canyon and San Francisquito Canyon; and the San Gabriel Mountains north of the National Forest boundary, including portions of Sand Canyon and -

Copperhead & Endangered Species Agkistrodon Contortrix

Natural Heritage Copperhead & Endangered Species Agkistrodon contortrix Program State Status: Endangered www.mass.gov/nhesp Federal Status: None Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife DESCRIPTION: Copperheads get their name due to their solid, relatively unmarked, coppery-colored head resembling the color of an old copper coin. As with all pit vipers, Copperheads have broad, triangularly shaped heads, with a distinct narrowing just behind the head. The eyes have vertically elliptical (catlike) pupils. There is a very thin line on each side of the face that separates the richer copper color of the top of the head from the lighter color of the lip area. The iris of the eye is pale gold, and the pupil is dark. On the body there is a series of dark brown to reddish, hourglass-shaped, cross bands. These are narrow in the middle of the body and broad to the sides. The ground color ranges from beige to tan. Body markings are continuous over the entire length of the body, including the tail. Young snakes are replicas of adults, except that the body has an overtone of light grey and the tip of the tail is yellow. Adult from Hampshire County; photo by Mike Jones/MassWildlife Adult Copperheads usually measure 60–90 cm (24–36 inches) in length; the newborn young are usually 18–23 ridge protrudes from the middle of each scale), giving cm (7–9 inches). Males usually have longer tails, but the snake a relatively rough-skinned appearance. females can grow to greater total lengths (up to 4 feet). There is no reliable external cue to differentiate the SIMILAR SPECIES IN MASSACHUSETTS: The sexes. -

Eastern Milksnake,Lampropeltis Triangulum

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2014 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2014. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 61 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 29 pp. Fischer, L. 2002. COSEWIC status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the milksnake Lampropeltis triangulum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-29 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Jonathan Choquette for writing the status report on the Eastern Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum) in Canada. This report was prepared under contract with Environment Canada and was overseen by Jim Bogart, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Amphibians and Reptiles Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Couleuvre tachetée (Lampropeltis triangulum) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Eastern Milksnake — Sketch of the Eastern Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum). -

A Systematic Review of the Great Basin Reptiles in the Collections of Brigham Young University and the University of Utah Wilmer W

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 26 Article 5 Number 3 – Number 4 12-31-1966 A systematic review of the Great Basin reptiles in the collections of Brigham Young University and the University of Utah Wilmer W. Tanner Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah Benjamin H. Banta Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Tanner, Wilmer W. and Banta, Benjamin H. (1966) "A systematic review of the Great Basin reptiles in the collections of Brigham Young University and the University of Utah," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 26 : No. 3 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol26/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE GREAT BASIN REPTILES IN THE COLLECTIONS OF BRIGHAM YOUNC; UNIVERSITY AND THE UNIVERSriY OF UTAH Wilmer W. Tanner and Benjamin H. Banta' Introduction This report is one of a planned series of analyses of reptile speci- mens taken from the Great Basin and now deposited in the major institutional repositories of the western United States. We hope and anticipate that such reports will provide a more adequate systematic and distributional picture of the Great Basin reptile fauna. At present we are concerned mainly with the species occurring in this region and specimen locality data If such can be completed we would then perhaps have a nearly complete list of species and subspecies occurring in the basin as well as the distribution limits of each.