Evidence for Equality the Future of Equality in Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Challenging Lesbian and Gay Inequalities in Education. Gender and Education Series. REPORT NO ISBN-0-335-19130-4 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 253P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 398 296 UD 031 103 AUTHOR Epstein, Debbie, Ed. TITLE Challenging Lesbian and Gay Inequalities in Education. Gender and Education Series. REPORT NO ISBN-0-335-19130-4 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 253p. AVAILABLE FROMOpen University Press, Celtic Court, 22 Ballmoor, Buckingham, MK18 1KW, England, United Kingdom ($27.50); Open University Press, 1900 Frost Road, Suite 101, Bristol, PA 19007. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academie Achievement; Elementary Secondary Education; *Equal Education; Foreign Countries; *Homophobia; *Homosexuality; Minority Groups; Peer Acceptance; Peer Relationship; *Self Esteem; Sex Education; *Social Discrimination; Social Support Groups; *Student Attitudes IDENTIFIERS *Bisexuality; Homosexual Teachers; United Kingdom ABSTRACT Educators in Britain have tended to ignore lesbian and gay issues, creating a gap that this book addresses by discussing the complex debates about sexuality and schooling. Contributors to this collection tell stories of distress and victimization and of achievement and support in the following: (1) "Introduction: Lesbian and Gay Equality in Education--Problems and Possibilities" (Debbie Epstein); (2)"So the Theory Was Fine" (Alistair, Dave, Rachel, and Teresa);(3) "Growing Up Lesbian: The Role of the School" (Marigold Rogers);(4) "A Burden of Aloneness" (Kola) ;(5) "Are You a Lesbian, Miss?" (Susan A. L. Sanders and Helena Burke);(6) "Victim of a Victimless Crime: Ritual and Resistance" -

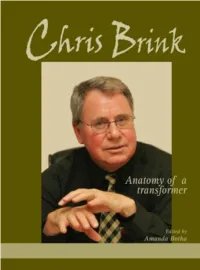

Chris Brink Anatomy of a Transformer

Chris Brink Anatomy of a transformer Editor Amanda Botha Chris Brink: Anatomy of a transformer Published by SUN PReSS, a division of AFRICAN SUN MeDIA Pty. (Ltd.) Ryneveld Street, Stellenbosch 7600 www.africansunmedia.co.za www.sun-e-shop.co.za Cover photograph: With recognition to Rapport Photo’s: With recognition to Anton Jordaan and Hennie Rudman, SSFD Design and page layout: Ilse Roelofse Concept design: Heloïse Davis Cover design: Ilse Roelofse All rights reserved Copyright © 2007 Stellenbosch University No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic, photographic or mechanical means, including photocopying and recording on record, tape or laser disk, on microfilm, via the Internet, by e-mail, or by any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission by the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-920109-80-6 e-ISBN: 978-1-920689-37-7 DOI: 10.18820/9781920689377 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRELIMINARIES i Foreword: Elize Botha ii Introduction: Amanda Botha iii Note from Council: Edwin Hertzog iv Short Curriculum Vitae: Chris Brink v Stellenbosch University: Vision statement 2012 PART I: FIVE YEARS OF TRANSFORMATION 1.1 Transformation as demythologisation 1.2 What is an Afrikaans university? 1.3 The state of the University PART II: KEY SPEECHES, DOCUMENTS AND VIEWS 2.1 Personal Vision Statement, 2001 2.1.1 Introduction 2.1.2 Personal Vision Statement for Stellenbosch University 2.1.3 Reaction 2.1.3.1 Maties choose a Rector and say: “We are open to new influences” – Hanlie Retief (Rapport, -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. I witnessed the demonstrations against Terrence McNally’s play, Corpus Christi, in 1999 at Edinburgh’s Bedlam Theatre, the home of the University’s student theatre company. But these protests were not taken seriously by any- one I knew: acknowledged as a nuisance, certainly, but also judged to be very good for publicity in the competitive Festival fringe. 2. At ‘How Was it for You? British Theatre Under Blair’, a conference held in London on 9 December 2007, the presentations of directors Nicholas Hytner, Emma Rice and Katie Mitchell, writers Mark Lawson, Kwame Kwei-Armah, Tanika Gupta and Mark Ravenhill, and actor and Equity Rep Malcolm Sinclair all included reflection upon issues of censorship, the policing of per- formance or indirect forms of constraint upon content. Ex-Culture Minister Tessa Jowell’s opening presentation also discussed censorship and the closure of Behzti. 3. Andrew Anthony, ‘Amsterdammed’, The Observer, 5 December 2004; Alastair Smart, ‘Where Angels Fear to Tread’, The Sunday Telegraph, 10 December 2006. 4. Christian Voice went on to organise protests at the theatre pro- duction’s West End venue and then throughout the country on a national tour. ‘Springer protests pour in to BBC’, BBC News, 6 January 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/tv_and_radio/4152433.stm [accessed 1 August 2007]. 5. Angelique Chrisafis, ‘Loyalist Paramilitaries Drive Playwright from His Home’, The Guardian, 21 December 2005. 6. ‘Tate “Misunderstood” Banned Work’, BBC News, 26 September 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/entertainment/arts/4281958.stm [accessed 1 August 2007]; for discussion of the Bristol Old Vic’s decision, see Ian Shuttleworth, ‘Prompt Corner’, Theatre Record, 25.23, 6 December 2005, pp. -

The Rosemarie Nathanson Charitable Trust the Shoresh Charitable Trust the R and S Cohen Foundation the Margolis Family the Kobler Trust

SPONSORS THE ROSEMARIE NATHANSON CHARITABLE TRUST THE SHORESH CHARITABLE TRUST THE R AND S COHEN FOUNDATION THE MARGOLIS FAMILY THE KOBLER TRUST BANK LEUMI (UK) DIGITAL MARKETING MEDIA TRAVEL GALA SPONSOR SPONSOR SPONSOR SPONSOR President: Hilton Nathanson Patrons Carolyn and Harry Black Peter and Leanda Englander Isabelle and Ivor Seddon Sir Ronald Cohen and Lady The Kyte Group Ltd Eric Senat Sharon Harel-Cohen Lord and Lady Mitchell Andrew Stone Honorary Patrons Honorary Life Patron: Sir Sydney Samuelson CBE Tim Angel OBE Romaine Hart OBE Tracy-Ann Oberman Helen Bamber OBE Sir Terry Heiser Lord Puttnam of Queensgate CBE Dame Hilary Blume Stephen Hermer Selwyn Remington Lord Collins of Mapesbury Lord Janner of Braunstone QC Ivor Richards Simon Fanshawe Samir Joory Jason Solomons Vanessa Feltz Lia van Leer Chaim Topol Sir Martin Gilbert Maureen Lipman CBE Michael Grabiner Paul Morrison Funding Contributors In Kind Sponsors Film Sponsors The Arthur Matyas & Jewish Genetic Disorders UK - The Mond Family Edward (Oded) Wojakovski with thanks to The Dr. Benjamin Fiona and Peter Needleman Charitable Foundation Angel Foundation The Normalyn Charitable Trust Anthony Filer Stella and Samir Joory Stuart and Erica Peters The Blair Partnership Joyce and David Kustow René Cassin Foundation The Ingram Family The Gerald Ronson Foundation The Rudnick Family Charlotta and Roger Gherson Veronique and Jonathan Lewis The Skolnick Family Jane and Michael Grabiner London Jewish Cultural Centre Velo Partners Dov Hamburger/ Carolyn and Mark Mishon Yachad Searchlight Electric The Lowy Mitchell Foundation 1 Welcome to the 16th UK JeWish Film Festival It is with enormous pleasure that I invite you to join us at the 16th UK Jewish Film Festival which, for the first time, will bring screenings simultaneously to London, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool and Manchester. -

THE SUSS-EX CLUB NEWSLETTER NO. 4 March

THE SUSS-EX CLUB NEWSLETTER NO. 4 March 2007 Welcome to this latest Suss-Ex Newsletter. The group is gradually building up some momentum, with a range of activities already behind us and a number of ex- citing ones ahead for you to note in your diary. So far this has been run by an infor- mal steering group chaired by former VC Sir Gordon Conway, but the time is ap- proaching when we can aim to set up a more formal and permanent structure. A working group is formulating proposals. Watch this spot. If you are a new recipient of this newsletter, you will find more information on the steering group and activities so far on the Suss-Ex Club website at http://www.sussex.ac.uk/suss-ex/ —also worth a glance from time to time by any members who would like to keep up with what is going on. CONTENTS: • Keeping in touch • Events Diary 2007 • Reports on past events • Obituaries • Emeritus Titles • Response Form KEEPING IN TOUCH: We believe that all those receiving this Newsletter by e-mail have given permission to be communicated with concerning activities and matters of likely interest to staff formerly employed on the University of Sussex campus. If we are not right in your case, please tell us! We could still do with alerting more former staff to the existence of the Club, and would welcome volunteers to take one of the following areas under their wing and do what they can to unearth and contact former colleagues and persuade them also to fill in the form giving their contact details (see http://www.sussex.ac.uk/suss- ex ), and thereby start receiving Suss-Ex Club communications. -

Legends of South African Science Ii

LEGENDS OF SOUTH AFRICAN SCIENCE II © Academy of Science of South Africa March 2020 ISBN 978-1-928496-01-4 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/assaf.2018/0036 Cite: Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf), (2019). Legends of South African Science II. [Online] Available at: DOI http://dx.doi. org/10.17159/assaf.2018/0036 Published by: Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf) PO Box 72135, Lynnwood Ridge, Pretoria, South Africa, 0040 Tel: +27 12 349 6600 • Fax: +27 86 576 9520 E-mail: [email protected] Reproduction is permitted, provided the source and publisher are appropriately acknowledged. The Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf) was inaugurated in May 1996. It was formed in response to the need for an Acade- my of Science consonant with the dawn of democracy in South Africa: activist in its mission of using science and scholarship for the benefit of society, with a mandate encompassing all scholarly disciplines that use an open-minded and evidence-based approach to build knowledge. ASSAf thus adopted in its name the term ‘science’ in the singular as reflecting a common way of enquiring rather than an aggregation of different disciplines. Its Members are elected, based on a combination of two principal criteria: academic excellence and significant contributions to society. The Parliament of South Africa passed the Academy of Science of South Africa Act (No 67 of 2001), which came into force on 15 May 2002. This made ASSAf the only academy of science in South Africa officially recognised by government and representing the country in the international community of science academies and elsewhere. -

Wednesday 06 October 2021

WEDNESDAY 06 OCTOBER 2021 08:30 – 09:30 REGISTRATION Registration TEA AND COFFEE ON ARRIVAL IGNITING CONVERSATIONS: THE ENGAGED UNIVERSITY CONFERENCE OPENING | SESSION 1-3 | 09:30 – 10:30 CONFERENCE WELCOME | Professor Sibongile Muthwa | Chairperson Universities South Africa | Venue 1 & Digital SESSION 1 Vice-Chancellor - Nelson Mandela University 09:30 – 09:40 SESSION 2 OFFICIAL CONFERENCE OPENING | Professor Ahmed Bawa | Chief Executive Officer - Venue 1 & Digital 09:40 – 09:50 Universities South Africa The National Higher Education Conference - 2021 - Reflecting on the Conference Theme SESSION 3 OPENING KEYNOTE ADDRESS | Dr Blade Nzimande | Honourable Minister of Higher Venue 1 & Digital 09:50 – 10:30 Education, Science and Technology SESSION 4 PLENARY SESSION 1, 2 & 3 Venue 1 & Digital 10:30 – 12:00 INTERNATIONAL SPEAKER SESSION SESSION 4A Venue 1 & Digital PLENARY SESSION 1 | Professor Ira Harkavy | Vice-Chancellor & Chair, International 10:30 - 11:00 Consortium on Higher Education SESSION 4A Venue 1 & Digital SESSION CHAIR | Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng | Vice-Chancellor - University of 10:30 - 11:00 Cape Town SESSION 4B PLENARY SESSION 2 | Dr Hilligje van't Land | Secretary-General, International Venue 1 & Digital 11:00 – 11:30 Association of Universities (IAU) | Executive Director, International Universities Bureau SESSION 4C PLENARY SESSION 3 Professor Joana Setzer| Professor at the Grantham Research 11:30 – 12:00 Institute on Climate Change & the Environment, LSE | United Kingdom SESSION 4B&C SESSION CHAIR | Professor Chris -

Radio 4 Christmas 2004 Highlights

CHRISTMAS HIGHLIGHTS Contents 2 Drama and Readings Factual A Chile Christmas 6 Correspondents Look Ahead 19 A Long Time Dead 4 Crib City 10 All Fingers And Thumbs 17 Crypt Music Kings 18 Ancient And Modern 8 Falling Up 7 Angelic Hosts 5 Food Quiz Special 13 Augustus Carp Esq. By Himself 6 Fractured 5 Boxing Clever 14 Hallelujah! 11 In The Bosom Of The Family 19 If The Slipper Fits 15 Just William – Doin’ Good 14 JM Barrie – Man And Boy 14 Lorna Doone 4 Magic Carpets 3 Peter And Wendy (rpt) 15 Opening Nights: Peter Pan Takes Flight 8 The Adventure Of The Christmas Pudding 9 People’s D-Day 13 The Dittisham Nativity 8 Remember Alistair Cooke 12 The Little White Bird 12 Robert Burns 20 The Nutcracker 3 Santarchy 11 The Sorcerer’s Apprentice 16 Sing Christmas 12 Soul Music 11 Comedy and Entertainment Start The Week 14 The Long Winter 9 Best Of I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue 15 The Reunion 13 Fanshawe Gets To The Bottom Of…Christmas 11 Veg Talk 19 Fanshawe Gets To The Bottom Of…The Party Season 19 Wall Of Death 4 Hamish And Dougal Hogmanay Special 19 Who Was Wenceslas And Who Decided He Was Good? 7 Lets Hear It For The King Of Judea 3 The Now Show Christmas Special 10 Religion Roy Hudd’s Tales From The Lodge Room 15 Steven Appleby’s Normal Christmas 8 Christmas In Bethlehem 11 The Write Stuff 17 Christmas Service 11 With Great Pleasure At Christmas 11 Daily Service 9 Festival Of Nine Lessons And Carols 9 Midnight Mass 9 Sunday Worship 13 The Choice 6 3 Saturday 18 December 2004 BBC RADIO 4 Saturday 18 December Magic Carpets 1/1 3.30-4.00pm Let’s Hear It For The King Of Judea 1/1 Seaside entertainer Tony Lidington (who has flown on a magic 10.30-11.00am carpet himself) explores the symbolism and language of carpets. -

Higher Education Management and Policy

Volume 21/1 Volume 2009 Higher Education Management and Policy JOURNAL OF THE PROGRAMME ON INSTITUTIONAL Higher Education MANAGEMENT IN HIGHER EDUCATION Management A Faustian Bargain? Institutional Responses to National and International Rankings Peter W.A. West 9 and Policy “Standards Will Drop” – and Other Fears about the Equality Agenda in Higher Education JOURNAL OF THE PROGRAMME Chris Brink 19 ON INSTITUTIONAL MANAGEMENT The Knowledge Economy and Higher Education: A System for Regulating IN HIGHER EDUCATION the Value of Knowledge Simon Marginson 39 Rankings and the Battle for World-Class Excellence: Institutional Strategies and Policy Choices Ellen Hazelkorn 55 What’s the Difference? A Model for Measuring the Value Added by Higher Education in Australia Higher Education Management and Policy Hamish Coates 77 Defining the Role of Academics in Accountability Elaine El-Khawas 97 The Growing Accountability Agenda: Progress or Mixed Blessing? Jamil Salmi 109 The Regional Engagement of Universities: Building Capacity in a Sparse Innovation Environment Paul Benneworth and Alan Sanderson 131 Subscribers to this printed periodical are entitled to free online access. If you do not yet have online access via your institution’s network, contact your librarian or, if you subscribe personally, send an e-mail to [email protected]. Volume 21/1 2009 ISSN 1682-3451 2009 SUBSCRIPTION (3 ISSUES) -:HRLGSC=XYZUUU: Volume 21/1 ����������������������� 89 2009 01 1 P 2009 JOURNAL OF THE PROGRAMME ON INSTITUTIONAL MANAGEMENT IN HIGHER EDUCATION Higher Education Management and Policy Volume 21/1 ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT The OECD is a unique forum where the governments of 30 democracies work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. -

Agenda and Papers for 1 February 2018 Board Meeting

Board Meeting Thursday 1 February 2018 Venue: S3.41 (New Boardroom), 3rd floor, Seacole building, 2 Marsham Street, SW1P 4DF Board breakfast 9.00am 75 mins Water Resources pre Stakeholder event Harvey Bradshaw 10.15am informative session with Peter Simpson CEO of 75 mins Anglian Water 1. Apologies Emma Howard Boyd 11.30am 2. Declarations of Interest Emma Howard Boyd 5 mins 3. Minutes of the Board meeting held on 5 Emma Howard Boyd December 2017 and matters arising 4. Topical Update items 4.1 Chief Executive’s update James Bevan 11.35am 4.2 25 Year Environment Plan and EU Exit Harvey Bradshaw 40 mins 5. Committee meetings – oral updates and forward 12.15pm look 20 mins 5.1 Pensions Joanne Segars 5.2 E&B including annual review Gill Weeks 5.3 FCRM Lynne Frostick 5.4 Audit and Risk Assurance including annual Gill Weeks (for review Karen Burrows) 6. Regular update items 6.1 Schemes of Delegation (for approval) Joanne Segars 12.35pm 6.2 Finance report (for information) Bob Branson 10 mins Lunch 12.45pm 30 mins 7. Defra head of function guests – Jac Broughton, Emma Howard Boyd 1.15pm HR Head of Function for the Defra Group and 60 mins John Seglias, DDTS Head of Function for the Defra Group Break 2.15pm 10 mins 8. FCRM GiA final indicative allocation for 2018/19 John Curtin 2.25pm (for approval) 20 mins 9. Charges items 9.1 Levies and Charges (for approval) Bob Branson 9.2 Strategic Review of Charges (for Harvey Bradshaw 2.45pm information) 45 mins 9.3 Mobilising More Money Harvey Bradshaw 10. -

EXPERT ADVISORY BOARD – MEMBERS' PROFILES (Updated

HEFCE LGM PROJECT: Leading Curriculum Change for Sustainability - Strategic Approaches to Quality Enhancement EXPERT ADVISORY BOARD – MEMBERS’ PROFILES (updated V2) Mr Anthony McClaran (Chair) Chief Executive, Quality Assurance Agency Anthony McClaran took up post as Chief Executive of QAA on 1 October 2009, after nearly six years as Chief Executive at UCAS. He joined UCAS in 1995 to lead the then Academic Services and Development department, and was appointed Deputy Chief Executive a year later. He became Acting Chief Executive in January 2003 and was appointed Chief Executive in December of that year. A graduate in English and American Literature from the University of Kent, Anthony began his career at the University of Warwick where, among other posts, he was Admissions Officer. In 1992 he moved to the University of Hull to take up the post of Academic Registrar, with responsibility for an office which included recruitment, admissions, student records, international affairs and the internal allocation of resources. In 1995 he was appointed Acting Registrar and Secretary. Anthony sat on the Council of the University of Gloucestershire from 1997 until 2005 and in September 2007 was appointed Chair of Council, a post he relinquished on taking up his QAA role. Professor Chris Brink Vice-Chancellor, Newcastle University Professor Chris Brink is the Vice-Chancellor of Newcastle University in the UK. He is the academic and executive head of the University, and serves on several Boards in Newcastle and the Northeast of England. At national level he is the Co-Chair of the Equality Challenge Unit (ECU), serves on the Board of the UK Quality Assurance Agency (QAA), and is a member of the Advisory Committee on Leadership, Governance and Management of the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). -

Enter the Man Aaron C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Enter the Man Aaron C. Thomas Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE & DANCE ENTER THE MAN By AARON C. THOMAS A Dissertation submitted to the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2012 Aaron C. Thomas defended this dissertation on October 19, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Mary Karen Dahl Professor Directing Dissertation Patricia Warren Hightower University Representative Elizabeth A. Osborne Committee Member Leigh H. Edwards Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want, first of all, to thank my advisor, Mary Karen Dahl, for believing in this project from the first and as her graduate students always say among ourselves for always making my questions smarter. Many years ago as I was speaking to Dr. Dahl about this project when it was only an idea, she said to me: and isn’t it interesting that Aristotle placed the moment of the greatest release at the same moment as the greatest violence. If I hadnt been convinced that she would be the perfect advisor before that moment, then that sentence certainly confirmed her as the ideal director of this project. I would also like to thank my dissertation committee, Leigh Edwards, Patricia Warren Hightower, Lynn Hogan, and Elizabeth Osborne.