Woodrow Wilson and a Third Nomination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Experience with Diplomacy and Military Restraint I

PART I: THE AmERICAN EXPERIENCE WITH DIPLOMACY AND MILITARY RESTRAINT i. Orphaned Diplomats: The American Struggle to Match Diplomacy with Power Jeremi Suri E. Gordon Fox Professor of History and Director, European Union Center of Excellence, University of Wisconsin, Madison Benjamin Franklin spent the American Revolution in Paris. He had helped to draft the Declaration of Independence in the summer of 1776, one of the most radical documents of the eighteenth century—sparking rebellion on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Serving as a representative for the Continental Congress in France during the next decade, Franklin became a celebrity. He was the enlightened idealist from the frontier, the man of principled action who enthralled onlookers in the rigid European class societies of the 1770s and ’80s. Franklin embodied the American critique of Old World society, economy, and diplomacy. He was one of many American revolutionaries to take aim at the degenerate world of powdered wigs, fancy uniforms, and silver-service dinners where the great men of Europe decided the fate of distant societies. Franklin was a representative of the enduring American urge to replace the diplomacy of aristocrats with the openness and freedom of democrats.1 Despite his radical criticisms of aristocracy, Franklin was also a prominent participant in Parisian salons. To the consternation of John Adams and John Jay, he dined most evenings with the most conservative elements of French high society. Unlike Adams, he did not refuse to dress the part. For all his frontiers- man claims, Franklin relished high-society silver-service meals, especially if generous portions of wine were available for the guests. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

16. a New Kind of First Lady: Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House

fdr4freedoms 1 16. A New Kind of First Lady: Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt at the dedication of a high school in their hometown of Hyde Park, New York, October 5, 1940. Having overcome the shyness that plagued her in youth, ER as First Lady displayed a great appetite for meeting people from all walks of life and learning about their lives and troubles. FDRL Eleanor Roosevelt revolutionized the role of First Lady. No writers; corresponded with thousands of citizens; and served presidential wife had been so outspoken about the nation’s as the administration’s racial conscience. affairs or more hardworking in its causes. ER conveyed to the Although polls at the time of her death in 1962 revealed American people a deep concern for their welfare. In all their ER to be one of the most admired women in the world, not diversity, Americans loved her in return. everyone liked her, especially during her husband’s presidency, When she could have remained aloof or adopted the when those who differed with her strongly held progressive ceremonial role traditional for First Ladies, ER chose to beliefs reviled ER as too forward for a First Lady. She did not immerse herself in all the challenges of the 1930s and ‘40s. shy away from controversy. Her support of a West Virginia She dedicated her tireless spirit to bolstering Americans Subsistence Homestead community spurred debate over against the fear and despair inflicted by the Great Depression the value of communal housing and rural development. By and World War II. -

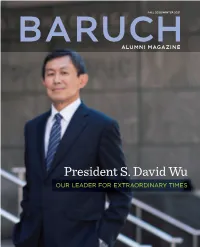

President S. David Wu

FALL 2020/WINTER 2021 BARUCHALUMNI MAGAZINE President S. David Wu OUR LEADER FOR EXTRAORDINARY TIMES MESSAGE FROM FALL 2020/WINTER 2021 THE PRESIDENT IN THIS ISSUE Dear Baruch Alumni, I feel incredibly honored and privileged to join the Baruch community at a pivotal moment in the College’s history. As the nation grapples with the pandemic, the resulting 6 CAMPUS WELCOME Baruch Alumni Magazine economic damage, and the reckoning to end systemic racism, the entire Baruch A Q&A with President S. David Wu: His Vision for Cheryl de Jong–Lambert community unified and overcame unimaginable challenges to continue core College Director of Communications operations and deliver distance learning while supporting our students to keep pace Baruch College and Public Higher Education in the U.S. EDITOR IN CHIEF: Diane Harrigan with their education. I have been impressed not only with Baruch’s remarkable, resilient Baruch’s new president, S. David Wu, PhD, talks personal history, first impressions, and bold initiatives, students, faculty, and staff but with the alumni community. Your welcome has been which include reimagining college education—Baruch style—in the new normal. Says President Wu, SENIOR EDITOR: Gregory M. Leporati genuine and heartfelt, your connection to your alma mater strong, and your appreciation “Baruch shows what is possible at a time when our country desperately needs a more robust and more GRAPHIC DESIGN: Vanguard for the value and impact of your Baruch education has been an inspiration for me. inclusive system of public higher education.” OFFICE OF ALUMNI RELATIONS AND VOLUNTEER ENGAGEMENT My first 100 days were illuminating and productive. -

The United States, Great Britain, the First World

FROM ASSOCIATES TO ANTAGONISTS: THE UNITED STATES, GREAT BRITAIN, THE FIRST WORLD WAR, AND THE ORIGINS OF WAR PLAN RED, 1914-1919 Mark C. Gleason, B.S. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major-Professor Robert Citino, Committee Member Michael Leggiere, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Gleason, Mark C. From Associates to Antagonists: The United States, Great Britain, the First World War, and the Origins of WAR PLAN RED, 1914-1919. Master of Arts (History), May 2012, 178 pp., bibliography, 144 titles. American military plans for a war with the British Empire, first discussed in 1919, have received varied treatment since their declassification. The most common theme among historians in their appraisals of WAR PLAN RED is that of an oddity. Lack of a detailed study of Anglo- American relations in the immediate post-First World War years makes a right understanding of the difficult relationship between the United States and Britain after the War problematic. As a result of divergent aims and policies, the United States and Great Britain did not find the diplomatic and social unity so many on both sides of the Atlantic aspired to during and immediately after the First World War. Instead, United States’ civil and military organizations came to see the British Empire as a fierce and potentially dangerous rival, worthy of suspicion, and planned accordingly. Less than a year after the end of the War, internal debates and notes discussed and circulated between the most influential members of the United States Government, coalesced around a premise that became the rationale for WAR PLAN RED. -

President Harry S Truman's Office Files, 1945–1953

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microforms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT HARRY S TRUMAN’S OFFICE FILES, 1945–1953 Part 2: Correspondence File UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microforms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT HARRY S TRUMAN’S OFFICE FILES, 1945–1953 Part 2: Correspondence File Project Coordinators Gary Hoag Paul Kesaris Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by David W. Loving A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, Maryland 20814-3389 LCCN: 90-956100 Copyright© 1989 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-151-7. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................ v Scope and Content Note ....................................................................................................... xi Source and Editorial Note ..................................................................................................... xiii Reel Index Reel 1 A–Atomic Energy Control Commission, United Nations ......................................... 1 Reel 2 Attlee, Clement R.–Benton, William ........................................................................ 2 Reel 3 Bowles, Chester–Chronological -

Eleanor Roosevelt and the Arthurdale Subsistence Housing Project

Volume 4, Issue No. 1. Turning Coal to Diamond: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Arthurdale Subsistence Housing Project Renée Trepagnier Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA ÒÏ Abstract: In 1933, Eleanor Roosevelt (ER), the First Lady of the United States, initiated a subsistence housing project, Arthurdale, funded by the federal government to help a poor coal mining town in West Virginia rise above poverty. ER spotlighted subsistence housing as a promising venture for poor American workers to develop economic stability and community unification. She encountered harsh pushback from the federal government, the American public, and private industries. Deemed communistic and excessively expensive, Arthrudale pushed the boundaries of federal government involvement in community organization. Bureaucratic and financial issues impacted the community’s employment rates, income, and community cooperation. ER persisted, perhaps too blindly, until the federal government declared the project a failure and pulled out to avoid further financial loses. ER’s involvement in Arthurdale’s administration and bureaucracy radically shifted the role of the First Lady, a position with no named responsibilities or regulations. Before ER, First Ladies never exercised authority in federally regulated projects and rarely publicly presented their opinions. Did ER’s involvement in Arthurdale hinder or promote the project’s success? Should a First Lady involve herself in federal policy? If so, how much authority should she possess? “Nothing we do in this world is ever wasted and I have come to the conclusion that practically nothing we ever do stands by itself. If it is good, it will serve some good purpose in the future. If it is evil, it may haunt us and handicap our efforts in unimagined ways” –Eleanor Roosevelt 1961 Crushing Poverty in West Virginia In the mid to late 19th century, industrialization developed in the United States, necessitating a demand for coal. -

Of-Biography - of $ -.*«*; Tubffo

! Of-Biography - Of $ -.*«*; Tubffo tive from South Carolina, born in JOHN C. CALHOUN Charleston January 2, 1797; at John CaJdvvell Calhoun was Portraits of Two South Carolinians tended Charleston College and the born at "the Long Canes set i •• ©© school of the Rev. Moses Wad- tlement" In what became Abbe- dell at Abbevule; was graduated ville County, March 18, 1782; V from the College of South Caro was graduated from Yale in lina (USC) in 1814; studied law 1804 and from Litch field law In State Department Collection 1814-1817; further pursued stu School, 1806, admitted to the bar dies in Paris and Edinburg in in 1807 and commenced prac 1818 and 1819; admitted to the By Kathleen Leicit tice In Abbeville; married Flo- bar in 1822 and commenced ride Bonneau Calhoun in 1811; practice in Charleston; member TN THE Department of State the works of those less promi Washington on February 28,1844. gave up the practice of law and of the State House of Repre 1 in Washington, there is a nent. Some are by unknown or James Gillespie Blaine con established himself as a plant sentatives 1820-22 and 1924-30; little-known collection of por obscure artists. j vened and presided over the er; member of the House of one of the founders and editor traits in oils of the men who All appear to be painted on first Pan American Conference Representative 1808-09; Repre of the Southern Review 1828-32; canvas. in 1889. Robert Bacon, mem sentative from South Carolina have served our country as attorney general for South Caro The title "Secretary ol State" ber of Genend Pershing©s stalf, 1811-17; was Secretary of War in Secretaries of State. -

FOR BARUCH COLLEGE “I Am Proud to Become the Eighth President of Baruch

SPRING/SUMMER 2020 BARUCHALUMNI MAGAZINE to have had the opportunity to partner with the trustees of SPRING/SUMMER 2020 Farewell Message from the Baruch College Fund (BCF), the College’s fundraising IN THIS ISSUE foundation. I especially thank the BCF presidents during my tenure—Helen Mills, Max Berger (’68, LLD-Hon. ’19), PRESIDENT Joel J. Cohen (’59), and Lawrence Simon (’65)—as well as past BCF Chairman Lawrence Zicklin (’57, LHD-Hon. 6 COVER STORY Baruch Alumni Magazine ’99) for their vision, dedication, and commitment. WALLERSTEIN The Wallerstein Decade: Celebrating Cheryl de Jong–Lambert Director of Communications Dear Friends, Meeting alumni, literally all over the world, has been 10 Years of Transformative Change among the highlights of my tenure and has shown me what As President Mitchel B. Wallerstein, PhD, winds down his EDITOR IN CHIEF: Diane Harrigan Let me begin by expressing my hope that you, your family, a committed, purposeful group you are. Thus, on behalf decade-long tenure in June, the Baruch community looks back SENIOR EDITOR: Gregory M. Leporati and friends are safe and well. Our country—and the New of this June’s graduating class and recent alumni, I have a on a period of historic accomplishments, transformation, and GRAPHIC DESIGN: Vanguard York region, in particular—has endured tremendous request: If you have or know of employment opportunities, a culture of proactive problem solving that continues to this day. challenges from the COVID-19 pandemic, and I send my OFFICE OF ALUMNI RELATIONS please share them with the College. Our graduating students Says Max Berger (’68, LLD-Hon. -

Baruch College MITCHELB

What’s Brewing? Alumni Innovate the Coffee Industry +A TRIBUTE TO WILLIAM NEWMAN (’47) Message from the President Whether you are one of the students whom we To mark their arrival—and to recognize the promotions, celebrated at Commencement on June 3, or you retirements, and achievements of the faculty as a whole— count yourself among the nearly 150,000 Baruch we hosted our inaugural Faculty Convocation, a special College alumni who span the globe, I am certain celebration that will become an annual fall tradition at that you can recall a faculty member—or several— the College. who had a big impact on your life. With deep appreciation to generous alumni, we were also I still remember with fondness and awe a professor who able to create four new endowed positions. At the Zicklin taught undergraduate political science, who shaped my School of Business, Lawrence Zicklin (’57) endowed the keen interest in public policy and motivated me to want Neuberger Berman/Zicklin Family Chair in Data Analytics to serve in the U.S. government, which I later did for in Accounting, now held by Vernon Richardson, PhD, and five years before becoming the dean of one of the leading Marvin C. Schwartz (’62) created the Neuberger Berman/ schools of public and international affairs. Schwartz Family Chair in Finance to focus on cutting-edge technology. A search is currently underway to fill the role. Our faculty are the intellectual heart and soul of Baruch. People who pursue careers in academia are making a With great thanks to ongoing support from Austin W. -

2018 Historic Autographs POTUS Autograph Checklist

2018 Historic Autographs Autograph Subjects Autograph Description Last Name Letter Chester Alan Arthur President A John Adams President A John Quincy Adams President A George Herbert Walker Bush President B George Walker Bush President B James Buchanan President B Calvin Coolidge President C Grover Cleveland President C James Earl Carter Jr President C William Jefferson Clinton President C Dwight David Eisenhower President E Gerald Rudolph Ford President F Millard Fillmore President F James Abram Garfield President G Ulysses S Grant President G Benjamin Harrison President H Herbert Clark Hoover President H Rutherford Birchard Hayes President H Warren Gamaliel Harding President H William Henry Harrison President H Andrew Jackson President J Andrew Johnson President J Lyndon Baines Johnson President J Thomas Jefferson President J James Knox Polk President K John Fitzgerald Kennedy President K Abraham Lincoln President L James Madison President M James Monroe President M William McKinley President M Richard Milhous Nixon President N Barack Hussein Obama President O Franklin Pierce President P Franklin Delano Roosevelt President R Ronald Wilson Reagan President R Theodore Roosevelt President R Donald Trump President T Harry S Truman President T John Tyler President T GroupBreakChecklists.com 2018 Historic Autographs Autograph Subject List Autograph Description Last Name Letter William Howard Taft President T Zachary Taylor President T Martin Van Buren President V George Washington President W Woodrow Wilson President W Spiro Agnew Vice President -

Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan Full Citation: Kendrick A Clements, “Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan,” Nebraska History 77 (1996): 167-176 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1996Bryan_SecState.pdf Date: 4/23/2013 Article Summary: Bryan’s foreign policy alternated between rash interventionism and timid isolationism. He proved to be too idealistic to serve successfully as secretary of state in a time of revolution and world war. Cataloging Information: Names: William Jennings Bryan, Woodrow Wilson, William McKinley, William Howard Taft, Edward M House, Roger Farnham Place Names: Philippines, Panama Canal, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Mexico, China, Japan Keywords: William Jennings Bryan, Woodrow Wilson, tariffs, income tax, Federal Reserve, Clayton Antitrust Act, Federal Trade Commission, Edward M House, treaties, German submarine warfare, League of Nations Photographs / Images: Bryan at his desk in the State Department, 1913; President Wilson and his cabinet, 1913; Bryan confirming ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment (direct election of US senators); paperweights that Bryan had had made out of old swords By Kendrick A.