Eleanor Roosevelt and the Arthurdale Subsistence Housing Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16. a New Kind of First Lady: Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House

fdr4freedoms 1 16. A New Kind of First Lady: Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt at the dedication of a high school in their hometown of Hyde Park, New York, October 5, 1940. Having overcome the shyness that plagued her in youth, ER as First Lady displayed a great appetite for meeting people from all walks of life and learning about their lives and troubles. FDRL Eleanor Roosevelt revolutionized the role of First Lady. No writers; corresponded with thousands of citizens; and served presidential wife had been so outspoken about the nation’s as the administration’s racial conscience. affairs or more hardworking in its causes. ER conveyed to the Although polls at the time of her death in 1962 revealed American people a deep concern for their welfare. In all their ER to be one of the most admired women in the world, not diversity, Americans loved her in return. everyone liked her, especially during her husband’s presidency, When she could have remained aloof or adopted the when those who differed with her strongly held progressive ceremonial role traditional for First Ladies, ER chose to beliefs reviled ER as too forward for a First Lady. She did not immerse herself in all the challenges of the 1930s and ‘40s. shy away from controversy. Her support of a West Virginia She dedicated her tireless spirit to bolstering Americans Subsistence Homestead community spurred debate over against the fear and despair inflicted by the Great Depression the value of communal housing and rural development. By and World War II. -

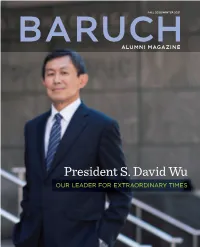

President S. David Wu

FALL 2020/WINTER 2021 BARUCHALUMNI MAGAZINE President S. David Wu OUR LEADER FOR EXTRAORDINARY TIMES MESSAGE FROM FALL 2020/WINTER 2021 THE PRESIDENT IN THIS ISSUE Dear Baruch Alumni, I feel incredibly honored and privileged to join the Baruch community at a pivotal moment in the College’s history. As the nation grapples with the pandemic, the resulting 6 CAMPUS WELCOME Baruch Alumni Magazine economic damage, and the reckoning to end systemic racism, the entire Baruch A Q&A with President S. David Wu: His Vision for Cheryl de Jong–Lambert community unified and overcame unimaginable challenges to continue core College Director of Communications operations and deliver distance learning while supporting our students to keep pace Baruch College and Public Higher Education in the U.S. EDITOR IN CHIEF: Diane Harrigan with their education. I have been impressed not only with Baruch’s remarkable, resilient Baruch’s new president, S. David Wu, PhD, talks personal history, first impressions, and bold initiatives, students, faculty, and staff but with the alumni community. Your welcome has been which include reimagining college education—Baruch style—in the new normal. Says President Wu, SENIOR EDITOR: Gregory M. Leporati genuine and heartfelt, your connection to your alma mater strong, and your appreciation “Baruch shows what is possible at a time when our country desperately needs a more robust and more GRAPHIC DESIGN: Vanguard for the value and impact of your Baruch education has been an inspiration for me. inclusive system of public higher education.” OFFICE OF ALUMNI RELATIONS AND VOLUNTEER ENGAGEMENT My first 100 days were illuminating and productive. -

President Harry S Truman's Office Files, 1945–1953

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microforms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT HARRY S TRUMAN’S OFFICE FILES, 1945–1953 Part 2: Correspondence File UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microforms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT HARRY S TRUMAN’S OFFICE FILES, 1945–1953 Part 2: Correspondence File Project Coordinators Gary Hoag Paul Kesaris Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by David W. Loving A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, Maryland 20814-3389 LCCN: 90-956100 Copyright© 1989 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-151-7. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................ v Scope and Content Note ....................................................................................................... xi Source and Editorial Note ..................................................................................................... xiii Reel Index Reel 1 A–Atomic Energy Control Commission, United Nations ......................................... 1 Reel 2 Attlee, Clement R.–Benton, William ........................................................................ 2 Reel 3 Bowles, Chester–Chronological -

FOR BARUCH COLLEGE “I Am Proud to Become the Eighth President of Baruch

SPRING/SUMMER 2020 BARUCHALUMNI MAGAZINE to have had the opportunity to partner with the trustees of SPRING/SUMMER 2020 Farewell Message from the Baruch College Fund (BCF), the College’s fundraising IN THIS ISSUE foundation. I especially thank the BCF presidents during my tenure—Helen Mills, Max Berger (’68, LLD-Hon. ’19), PRESIDENT Joel J. Cohen (’59), and Lawrence Simon (’65)—as well as past BCF Chairman Lawrence Zicklin (’57, LHD-Hon. 6 COVER STORY Baruch Alumni Magazine ’99) for their vision, dedication, and commitment. WALLERSTEIN The Wallerstein Decade: Celebrating Cheryl de Jong–Lambert Director of Communications Dear Friends, Meeting alumni, literally all over the world, has been 10 Years of Transformative Change among the highlights of my tenure and has shown me what As President Mitchel B. Wallerstein, PhD, winds down his EDITOR IN CHIEF: Diane Harrigan Let me begin by expressing my hope that you, your family, a committed, purposeful group you are. Thus, on behalf decade-long tenure in June, the Baruch community looks back SENIOR EDITOR: Gregory M. Leporati and friends are safe and well. Our country—and the New of this June’s graduating class and recent alumni, I have a on a period of historic accomplishments, transformation, and GRAPHIC DESIGN: Vanguard York region, in particular—has endured tremendous request: If you have or know of employment opportunities, a culture of proactive problem solving that continues to this day. challenges from the COVID-19 pandemic, and I send my OFFICE OF ALUMNI RELATIONS please share them with the College. Our graduating students Says Max Berger (’68, LLD-Hon. -

Baruch College MITCHELB

What’s Brewing? Alumni Innovate the Coffee Industry +A TRIBUTE TO WILLIAM NEWMAN (’47) Message from the President Whether you are one of the students whom we To mark their arrival—and to recognize the promotions, celebrated at Commencement on June 3, or you retirements, and achievements of the faculty as a whole— count yourself among the nearly 150,000 Baruch we hosted our inaugural Faculty Convocation, a special College alumni who span the globe, I am certain celebration that will become an annual fall tradition at that you can recall a faculty member—or several— the College. who had a big impact on your life. With deep appreciation to generous alumni, we were also I still remember with fondness and awe a professor who able to create four new endowed positions. At the Zicklin taught undergraduate political science, who shaped my School of Business, Lawrence Zicklin (’57) endowed the keen interest in public policy and motivated me to want Neuberger Berman/Zicklin Family Chair in Data Analytics to serve in the U.S. government, which I later did for in Accounting, now held by Vernon Richardson, PhD, and five years before becoming the dean of one of the leading Marvin C. Schwartz (’62) created the Neuberger Berman/ schools of public and international affairs. Schwartz Family Chair in Finance to focus on cutting-edge technology. A search is currently underway to fill the role. Our faculty are the intellectual heart and soul of Baruch. People who pursue careers in academia are making a With great thanks to ongoing support from Austin W. -

1924 the True Beginnings of the Army Industrial College Can Be T

CHAPTER 2 THE ORIGINS OF THE ARMY INDUSTRIAL COLLEGE, 1918 - 1924 The true beginnings of the Army Industrial College can be traced to our experience in World War I and its aftermath. The United States relatively poor performance in industrial mobilization to support American entry in that conflict prompted a series of post-war inquiries in Congress and the War Department aimed at finding ways to put in place systems and professionally educated senior leaders capable of responding to any future contingency. The Army Industrial College was founded as part of the national security initiatives in this era. WORLD WAR I: THE AFTERMATH Wartime Experience When the United States entered the war in April, 1917, hostilities in Europe had already been raging for nearly three years. Woodrow Wilson, re-elected to the Presidency in 1916 on the Democratic Party's reminder that, "he kept us out of war," now faced the challenge of a massive conflict in France. Giving way to a heretofore strong national sentiment of isolationism, the country sent its young men to "kill the Kaiser," and rallied in support of "the war to end all wars," a war that promised to "make the world safe for democracy" (Coffman, 1968; Morison, 1965). General John J. Pershing and a few elements of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) reached Paris on Independence Day in the summer of 1917, but delays in recruitment (a Selective Service law was eventually enacted), training, and transportation delayed significant American participation in the fighting until the spring of 1918 (Morison, 1965; Garraty, 1987). Despite the advantage of its late entry into the war, the United States was unprepared to support the logistical needs of what was arguably its first large scale conflict in which sophisticated modern equipment was introduced in sufficient numbers to influence the outcome of events. -

BENEDICT, STEPHEN: Papers, 1952-2004

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS BENEDICT, STEPHEN: Papers, 1952-2004 Accessions A71-39, A89-13, A90-8, A93-8, A93-8/1, A03-13, A04-10, A04-10/1, A07-12 Processed by: HP, VJA Date Completed: March 2014 The papers of Stephen Benedict, assistant to Dr. Gabriel Hauge, research director of Citizens for Eisenhower, 1951-53, assistant to the Administrative Assistant to the President for Economic Affairs, 1953-54, Assistant Staff Secretary, 1954-55, were deposited in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library in 1970, 1989, 1990, 1992 and 1993 by Mr. Benedict. In December 1970 Mr. Benedict executed an instrument of gift for these papers. The donor retains all literary property rights in his own writings in all papers donated to the U.S. Government. After his death the literary property rights in such writings will pass to the U.S. Linear feet shelf space occupied: 5.6 Approximate number of pages: 9,000 By agreement with the donor the following classes of documents will be withheld from research use: 1. Papers relating to the family and private business affairs of the donor. 2. Papers relating to the family and private business affairs of other persons who have had correspondence with the donor. 3. Papers relating to investigations of individuals or to appointments and personnel matters. 4. Papers containing statements made by or to the donor in confidence unless in the judgment of the Director of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library the reason for the confidentiality no longer exists. 5. All other papers which contain information or statements that might be used to injure, harass, or damage any living person. -

Cassie Connor Collection, Mss

Cassie Connor Collection A Register – 1934-1969, No Date Creator: Cassie Connor Collection Number: Mss 286 Title: Cassie Connor Collection Abstract: This material was collected by Cassie Connor, longtime secretary of James F. Byrnes, which gives additional insight into the work of the former Senator, advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Supreme Court Justice, Secretary of State under President Harry Truman, and Governor of South Carolina. Quantity: .65 cubic feet consisting of 10 folders, three bound volumes and 128 photographs in 3 boxes. Scope and Content Note The papers include correspondence, photographs, postcards, shorthand notes, travel documents, and bound material. The correspondence in this collection is divided into two subsets. The first includes items received by James F. Byrnes between the years 1934-1958. Among these items are letters from political figures such as President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill. In addition, there are letters from notable Hollywood figures such as Spencer Tracy and Clark Gable. The second set of correspondence contains material that Cassie Connor either sent or received. These include received items from relatives stationed overseas during World War II as well as letters from Bernard Baruch. There are 128 photographs that depict Byrnes, Connor, and members of various U.S. delegations and political figures that accompanied them on diplomatic missions such as Potsdam in 1945 and the Paris Peace Conference in 1946. Of note are six postcards addressed to Hermann Göring from German well-wishers concerning the birth of his daughter Edda in 1938. These were found in the book Hermann Göring Redun und Aufsatze from this collection. -

The White House Correspondence and Memoranda Series

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of The Papers of John Foster Dulles and of Christian A. Herter, 1953-1961 THE WHITE HOUSE CORRESPONDENCE AND MEMORANDA SERIES UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA The Presidential Documents Series The Papers of John Foster Dulles and of Christian A. Herter, 1953-1961 THE WHITE HOUSE CORRESPONDENCE AND MEMORANDA SERIES Microfilmed from the holdings of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester A microfilm project of University Publications of America, Inc. 44 North Market Street • Frederick, Maryland 21701 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dulles, John Foster, 1888-1959. The papers of John Foster Dulles and of Christian A. Herter, 1953-1961 [microform]. (The White House correspondence and memoranda series) (The Presidential documents series) "Microfilmed from the holdings of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library." Includes index. 1. United States-Foreign relations-1953-1961-- Sources. 2. Dulles, John Foster, 1888-1959--Archives. 3. Herter, Christian Archibald, 1895-1966-Archives. I. Herter, Christian Archibald, 1895-1966. II. Lester, Robert. III. Dwight D. Eisenhower Library. IV. Title. V. Series. VI. Series: Presidential documents series. [E835] 327.73 87-13343 ISBN 0-89093-891-1 Copyright © 1986 by University Publications of America, Inc. All rights reserved. ISBN 0-89093-891-1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronym List v Scope and Content Note vii Reel Index Reels 1 -4 John Foster Dulles: White House Memoranda Series Chronological Subseries 1 Reel 5 John Foster Dulles: White House Memoranda Series cont. Chronological Subseries cont 14 General Foreign Policy Subseries 15 Intelligence Subseries 16 Internal Security Subseries 16 John Foster Dulles: Draft Presidential Correspondence and Speeches Series 17 Reels 6-7 John Foster Dulles: Draft Presidential Correspondence and Speeches Series cont 17 Reel 8 John Foster Dulles: Draft Presidential Correspondence and Speeches Series cont 23 Christian A. -

Box Folder 12 9 "Which Way America, Next Tuesday?" 1948-1952

MS-763: Rabbi Herbert A. Friedman Collection, 1930-2004. Series E: Sermons, Speeches, and Writings, 1933-1959. Box Folder 12 9 "Which Way America, Next Tuesday?" 1948-1952. For more information on this collection, please see the finding aid on the American Jewish Archives website. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 513.487.3000 AmericanJewishArchives.org WHICH WAY .AMERICA'f N J ) A Pre-Election Sermon October 31, 1952 II This u a}Jol!lll&a sermon 11f._a1a1d with the eibtion ilP-- J,W"'~~I y '"' riv ....) mltr<l next TuesdaY., and yet I want you all to understand that this i\ is not a partisan, political appeal. I have attempted to keep my thinking on as lofty and non-partisan basis as is possible, and ( -~ " Vi I have attempted to 4i~eat myself rather 1ST the moral and spiritual issues which I feel are involved in this election, than ""-ao tthe immediate candidates. Because I have done this, I feel that there is no impropriety 1n my using the pulpit as the forum from which to direct to you these remarks. I am a stranger to Wisconsin• ~et the .famous tradition of • this state is notu.nknown to me, or, for that matter, to any stu_dent of government in .America. There was a tiDe when this state led the nation in much of the social engineering that has so immeasurably benefited the life of the average citizen. There was a time when . l LJ..\\ "1\-(_ JJ (A....,...._, I ~ ft I y l i ,.,.. Sf f this state actually gave its name to an idea • THE WISCONSIN IDEA • /ft - 2- which we studied in the text-books of political and economic science as an &xemplar of progressive government. -

A Simple Code of Ethics: a History of the Moral Purpose Inspiring Federal Regulation of the Securities Industry John H

Hofstra Law Review Volume 29 | Issue 4 Article 2 2001 A Simple Code of Ethics: A History of the Moral Purpose Inspiring Federal Regulation of the Securities Industry John H. Walsh Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Walsh, John H. (2001) "A Simple Code of Ethics: A History of the Moral Purpose Inspiring Federal Regulation of the Securities Industry," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 29: Iss. 4, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol29/iss4/2 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walsh: A Simple Code of Ethics: A History of the Moral Purpose Inspiring A SIMPLE CODE OF ETHICS: A HISTORY OF THE MORAL PURPOSE INSPIRING FEDERAL REGULATION OF THE SECURITIES INDUSTRY John H. Walsh: I. INTRODUCTION The idea that government regulation can serve a moral purpose has fallen into disrepute. Professor Henry G. Manne, an influential legal scholar,' has been particularly outspoken in this regard. "Morals," he wrote, "are a private luxury. Carried into the arena of serious debate on public policy, moral arguments are frequently either sham or a refuge for the intellectually bankrupt."2 Indeed, he suggests, to make a personal statement about the immorality of a particular type of securities transaction is to confuse oneself with God.? It was not always so. -

The Shared Mission of Herbert Hoover and Harry S. Truman to Alleviate Global Hunger in a Postwar World

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 7-9-2018 A Mutual Charge: the Shared Mission of Herbert Hoover and Harry S. Truman to Alleviate Global Hunger in a Postwar World Brian Douglas Reese Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Reese, Brian Douglas, "A Mutual Charge: the Shared Mission of Herbert Hoover and Harry S. Truman to Alleviate Global Hunger in a Postwar World" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4478. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6362 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Mutual Charge: The Shared Mission of Herbert Hoover and Harry S. Truman To Alleviate Global Hunger in a Postwar World by Brian Douglas Reese A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: David A. Horowitz, Chair Joseph Bohling Chia Yin Hsu Gerald Sussman Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Brian Douglas Reese Abstract Famine and destitution stemming from the Second World War had spread across the European continent and parts of Asia by mid-1945. Recognizing the need for recovery and survival in those regions, President Harry S. Truman at the recommendation of several Cabinet members, summoned ex-President Herbert Hoover for advice on how the United States should proceed in offering aid beyond the earlier efforts of the United Nations Rehabilitation and Relief Administration and other relief sources.