Churchill and Britain's 'Financial Dunkirk'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HEBEELE, Gerald Clarence, 1932- the PREDICAMENT of the BRITISH UNIONIST PARTY, 1906-1914

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68-3000 HEBEELE, Gerald Clarence, 1932- THE PREDICAMENT OF THE BRITISH UNIONIST PARTY, 1906-1914. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 History, modem University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © Copyright by Gerald Clarence Heberle 1968 THE PREDICAMENT OF THE BRITISH UNIONIST PARTY, 1906-1914 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gerald c / Heberle, B.A., M.A, ******* The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by B k f y f ’ P c M k ^ . f Adviser Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my deepest gratitude to Professor Philip P. Poirier of the Department of History, The Ohio State University, Dr. Poirier*s invaluable advice, his unfailing patience, and his timely encouragement were of immense assistance to me in the production of this dissertation, I must acknowledge the splendid service of the staff of the British Museum Manuscripts Room, The Librarian and staff of the University of Birmingham Library made the Chamberlain Papers available to me and were most friendly and helpful. His Lordship, Viscount Chilston, and Dr, Felix Hull, Kent County Archivist, very kindly permitted me to see the Chilston Papers, I received permission to see the Asquith Papers from Mr, Mark Bonham Carter, and the Papers were made available to me by the staff of the Bodleian Library, Oxford University, To all of these people I am indebted, I am especially grateful to Mr, Geoffrey D,M, Block and to Miss Anne Allason of the Conservative Research Department Library, Their cooperation made possible my work in the Conservative Party's publications, and their extreme kindness made it most enjoyable. -

London Calling: BBC External Services, Whitehall and the Cold War 1944- 57

London calling: BBC external services, Whitehall and the cold war 1944- 57. Webb, Alban The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/1577 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] LONDON CALLING: SSC EXTERNAL SERVICES, WHITEHALL AND THE COLD WAR, 1944-57 ALBAN WEBB Queen Mary College, University of London A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) 1 Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: '~"\ ~~Ue6b Alban Webb Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: Alban Webb ABSTRACT The Second World War had radically changed the focus of the BBC's overseas operation from providing an imperial service in English only, to that of a global broadcaster speaking to the world in over forty different languages. The end of that conflict saw the BBC's External Services, as they became known, re-engineered for a world at peace, but it was not long before splits in the international community caused the postwar geopolitical landscape to shift, plunging the world into a cold war. At the British government's insistence a re-calibration of the External Services' broadcasting remit was undertaken, particularly in its broadcasts to Central and Eastern Europe, to adapt its output to this new and emerging world order. -

The Attlee Governments

Vic07 10/15/03 2:11 PM Page 159 Chapter 7 The Attlee governments The election of a majority Labour government in 1945 generated great excitement on the left. Hugh Dalton described how ‘That first sensa- tion, tingling and triumphant, was of a new society to be built. There was exhilaration among us, joy and hope, determination and confi- dence. We felt exalted, dedication, walking on air, walking with destiny.’1 Dalton followed this by aiding Herbert Morrison in an attempt to replace Attlee as leader of the PLP.2 This was foiled by the bulky protection of Bevin, outraged at their plotting and disloyalty. Bevin apparently hated Morrison, and thought of him as ‘a scheming little bastard’.3 Certainly he thought Morrison’s conduct in the past had been ‘devious and unreliable’.4 It was to be particularly irksome for Bevin that it was Morrison who eventually replaced him as Foreign Secretary in 1951. The Attlee government not only generated great excitement on the left at the time, but since has also attracted more attention from academics than any other period of Labour history. Foreign policy is a case in point. The foreign policy of the Attlee government is attractive to study because it spans so many politically and historically significant issues. To start with, this period was unique in that it was the first time that there was a majority Labour government in British political history, with a clear mandate and programme of reform. Whereas the two minority Labour governments of the inter-war period had had to rely on support from the Liberals to pass legislation, this time Labour had power as well as office. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Recall of Mps

House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee Recall of MPs First Report of Session 2012–13 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 21 June 2012 HC 373 [incorporating HC 1758-i-iv, Session 2010-12] Published on 28 June 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider political and constitutional reform. Current membership Mr Graham Allen MP (Labour, Nottingham North) (Chair) Mr Christopher Chope MP (Conservative, Christchurch) Paul Flynn MP (Labour, Newport West) Sheila Gilmore MP (Labour, Edinburgh East) Andrew Griffiths MP (Conservative, Burton) Fabian Hamilton MP (Labour, Leeds North East) Simon Hart MP (Conservative, Camarthen West and South Pembrokeshire) Tristram Hunt MP (Labour, Stoke on Trent Central) Mrs Eleanor Laing MP (Conservative, Epping Forest) Mr Andrew Turner MP (Conservative, Isle of Wight) Stephen Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Bristol West) Powers The Committee’s powers are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in Temporary Standing Order (Political and Constitutional Reform Committee). These are available on the Internet via http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmstords.htm. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/pcrc. A list of Reports of the Committee in the present Parliament is at the back of this volume. -

Leo Amery at the India Office, 1940 – 1945

AN IMPERIALIST AT BAY: LEO AMERY AT THE INDIA OFFICE, 1940 – 1945 David Whittington A thesis submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education August 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii GLOSSARY iv INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTERS I LITERATURE REVIEW 10 II AMERY’S VIEW OF ATTEMPTS AT INDIAN CONSTITUTIONAL 45 REFORM III AMERY FROM THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ACT OF 1935 75 UNTIL THE AUGUST OFFER OF 1940 IV FROM SATYAGRAHA TO THE ATLANTIC CHARTER 113 V THE CRIPPS MISSION 155 VI ‘QUIT INDIA’, GANDHI’S FAST AND SOCIAL REFORM 205 IN INDIA VII A SUCCESSOR TO LINLITHGOW, THE STERLING BALANCES 253 AND THE FOOD SHORTAGES VIII FINAL ATTEMPTS AT CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM BEFORE THE 302 LABOUR ELECTION VICTORY CONCLUSION 349 APPENDICES 362 LIST OF SOURCES CONSULTED 370 ABSTRACT Pressure for Indian independence had been building up throughout the early decades of the twentieth century, initially through the efforts of the Indian National Congress, but also later, when matters were complicated by an increasingly vocal Muslim League. When, in May 1940, Leo Amery was appointed by Winston Churchill as Secretary of State for India, an already difficult assignment had been made more challenging by the demands of war. This thesis evaluates the extent to which Amery’s ultimate failure to move India towards self-government was due to factors beyond his control, or derived from his personal shortcomings and errors of judgment. Although there has to be some analysis of politics in wartime India, the study is primarily of Amery’s attempts at managing an increasingly insurgent dependency, entirely from his metropolitan base. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

16. a New Kind of First Lady: Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House

fdr4freedoms 1 16. A New Kind of First Lady: Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt at the dedication of a high school in their hometown of Hyde Park, New York, October 5, 1940. Having overcome the shyness that plagued her in youth, ER as First Lady displayed a great appetite for meeting people from all walks of life and learning about their lives and troubles. FDRL Eleanor Roosevelt revolutionized the role of First Lady. No writers; corresponded with thousands of citizens; and served presidential wife had been so outspoken about the nation’s as the administration’s racial conscience. affairs or more hardworking in its causes. ER conveyed to the Although polls at the time of her death in 1962 revealed American people a deep concern for their welfare. In all their ER to be one of the most admired women in the world, not diversity, Americans loved her in return. everyone liked her, especially during her husband’s presidency, When she could have remained aloof or adopted the when those who differed with her strongly held progressive ceremonial role traditional for First Ladies, ER chose to beliefs reviled ER as too forward for a First Lady. She did not immerse herself in all the challenges of the 1930s and ‘40s. shy away from controversy. Her support of a West Virginia She dedicated her tireless spirit to bolstering Americans Subsistence Homestead community spurred debate over against the fear and despair inflicted by the Great Depression the value of communal housing and rural development. By and World War II. -

Trade-Union Policy Between the Wars the Case of Holidays with Pay in Britain*

STEPHEN G. JONES TRADE-UNION POLICY BETWEEN THE WARS THE CASE OF HOLIDAYS WITH PAY IN BRITAIN* Most standard histories of Britain between the wars refer to the develop- ment of holidays with pay, albeit briefly. It is widely acknowledged that by the end of the 1930's the majority of the British working population benefited from a paid holiday. The crucial initiative, so it is claimed, was the Holidays with Pay Act of 1938, which gave Parliamentary approval to the principle of payment of wages during holidays.1 Clearly the growth of paid holidays is seen as yet another instance of a more affluent Britain, an integral element of the growth of leisure.2 However, there has been very little detailed discussion of the paid-holiday-policy option and the precise reasons for the formulation and implementation of that policy. This neglect is rather surprising given the popular support for this "fringe benefit", which was perceived as providing a certain degree of financial security during the annual break from the rigours of work. It is true that there has been more specialised treatment, but even this is of a general nature, with little reference to the industrial and political struggle for holidays with pay.3 * I would like to thank Dr M. E. Rose, Professor A. E. Musson and members of the Editorial Board for their helpful comments. 1 See C. L. Mowat, Britain Between the Wars 1918-1940 (London, 1955), p. 501; D. H. Aldcroft, The Inter-War Economy: Britain, 1919-1939 (London, 1970), p. 366; N. Branson and M. -

Public Health the Vision and the Challenge

THE ROCK CARLING FELLOWSHIP 1997 Public Health The vision and the challenge THE ROCK CARLING FELLOWSHIP 1997 PUBLIC HEALTH The vision and the challenge The pursuit of public health can have no finality... The problems of public health are changing rapidly with increasing medical knowledge and changes in social and economic conditions, the age distribution of the population and the outlook of the people. Sixth Annual Report of the Department of Health for Scotland 1934 Walter W Holland CBE, FRCP, FFPHM LSE Health, London School of Economics and Political Science London AND Susie Stewart DL, MA, HON MFPHM Department of Public Health, University of Glasgow Glasgow Published by The Nuffield Trust 59 New Cavendish Street, London WIM 7RD ISBN 1-902089-10-3 © Nuffield Trust 1998 Publications Committee Sir Derek Mitchell, KCB, cvo Professor John Ledingham, DM, FRCP John Wyn Owen, CB Designed by Benjamin Rowntree Reports Limited PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY BIDDLES & CO The Rock Carling Fellowship commemorates the late Sir Ernest Rock Carling for many years a governing Trustee and Chairman of the Medical Advisory Committee of the Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust. It was stipulated that each holder of the Fellowship will seek to review in a monograph the state of knowledge and activity in one of the fields in which Sir Ernest had been particularly interested, and which is within the purposes of the Trust. The arrangements provide that the monograph will be introduced by a public lecture given at a recognised Medical Teaching Centre in the United -

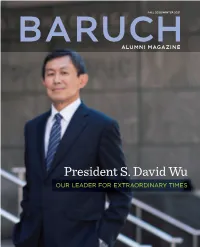

President S. David Wu

FALL 2020/WINTER 2021 BARUCHALUMNI MAGAZINE President S. David Wu OUR LEADER FOR EXTRAORDINARY TIMES MESSAGE FROM FALL 2020/WINTER 2021 THE PRESIDENT IN THIS ISSUE Dear Baruch Alumni, I feel incredibly honored and privileged to join the Baruch community at a pivotal moment in the College’s history. As the nation grapples with the pandemic, the resulting 6 CAMPUS WELCOME Baruch Alumni Magazine economic damage, and the reckoning to end systemic racism, the entire Baruch A Q&A with President S. David Wu: His Vision for Cheryl de Jong–Lambert community unified and overcame unimaginable challenges to continue core College Director of Communications operations and deliver distance learning while supporting our students to keep pace Baruch College and Public Higher Education in the U.S. EDITOR IN CHIEF: Diane Harrigan with their education. I have been impressed not only with Baruch’s remarkable, resilient Baruch’s new president, S. David Wu, PhD, talks personal history, first impressions, and bold initiatives, students, faculty, and staff but with the alumni community. Your welcome has been which include reimagining college education—Baruch style—in the new normal. Says President Wu, SENIOR EDITOR: Gregory M. Leporati genuine and heartfelt, your connection to your alma mater strong, and your appreciation “Baruch shows what is possible at a time when our country desperately needs a more robust and more GRAPHIC DESIGN: Vanguard for the value and impact of your Baruch education has been an inspiration for me. inclusive system of public higher education.” OFFICE OF ALUMNI RELATIONS AND VOLUNTEER ENGAGEMENT My first 100 days were illuminating and productive. -

The Relationship of the Home Office and the Ministry Of

THE RELATIONSHIP OF THE HOME OFFICE AND THE MINISTRY OF LABOUR WITH THE TREASURY ESTABLISHMENT DIVISION 1919-1946 AN EVALUATION OF CONTRASTING NEEDS NORMAN GEORGE PRICE Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD London School of Economics (University of London) 1 UMI Number: U042642 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U042642 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 t h e s e s F 68 nu-oaaiS ABSTRACT The thesis examines three Departments of the British Home Civil Service from 1919 to 1946: the Home Office, the Ministry of Labour and the Treasury Establishment Division. The study investigates the contrasting needs, in establishment terms, of an old "Secretary of State" department the Home Office, performing a largely regulatory role, with a new department the Ministry of Labour performing an administrative role, and the relationship of both over establishment matters with the Treasury. The study assesses the roles of individual Administrative Class civil servants in the three departments from the rank of Principal to Permanent Secretary: with particular reference to the relationships existing between the Permanent Secretaries of the two departments and the Permanent Secretaries of the Treasury and their Controllers of Establishments.