Rhetorical Qualities in the Campaign Speeches of Adlai Ewing Stevenson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

More Than a Municipal Campaign: Speech in Haverhill, Massachusetts (November 27, 1899)

More Than a Municipal Campaign: Speech in Haverhill, Massachusetts (November 27, 1899) Ladies and Gentlemen, Citizens of Haverhill:— A year ago the name of Haverhill was flashed around the world. On Wednesday next [Dec. 6, 1899] the magnificent victory achieved then will have ben ratified by an increased majority. This is something more than a municipal campaign. There are issues involved that are of vital and commanding interest to every man, woman, and child in Haverhill, in Massachusetts, throughout the length and breadth of the land. The competitive system, with its extreme wealth upon the one hand, its abject and widespread poverty upon the other, its political corruption, its economic servitude, its social demoralization is on trial. What pen or tongue, from primeval man to the dullest intellect, can describe the effect of this struggle upon the great mass of the working people? Multiplied millions of them answer to the description of the embruted peasant in the poem of Edwin Markham, a poem fraught with such significance that it blazed the immortality of the author on wings of lightning around the world: Bowed by the weight of centuries he leans Upon his hoe and gazes on the ground, The emptiness of ages in his face, And on his back the burden of the world. Who made him dead to rapture and despair, A thing that grieves not and that never hopes. Stolid and stunned, a brother to the ox? Who loosened and let down this brutal jaw? Whose was the hand that slanted back this brow? Whose breath blew out the light within this brain? 1 The capitalist system must answer for this appalling indictment at the bar of humanity. -

How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2019 Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates Gary M. Bogers University of Central Florida Part of the Music Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Bogers, Gary M., "Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates" (2019). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 511. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/511 MUSIC AND THE PRESIDENCY: HOW CAMPAIGN SONGS SOLD THE IMAGE OF PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES by GARY MICHAEL BOGERS JR. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Music Performance in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2019 Thesis Chair: Dr. Scott Warfield Co-chairs: Dr. Alexander Burtzos & Dr. Joe Gennaro ©2019 Gary Michael Bogers Jr. ii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I will discuss the importance of campaign songs and how they were used throughout three distinctly different U.S. presidential elections: the 1960 campaign of Senator John Fitzgerald Kennedy against Vice President Richard Milhouse Nixon, the 1984 reelection campaign of President Ronald Wilson Reagan against Vice President Walter Frederick Mondale, and the 2008 campaign of Senator Barack Hussein Obama against Senator John Sidney McCain. -

US Representative, 5Th District - Democratic Party - Vote for One

Unofficial results Cumulative Results Marion County, Oregon Registered Voters Official Election Results May 15, 2018 Primary Election 44886 of 194881 = 23.03 % Run Time 3:28 PM Precincts Reporting Run Date 05/16/2018 5/15/2018 123 of 123 = 100.00 % Page 1 of 93 US Representative, 5th District - Democratic Party - Vote for one Choice Party Ballots Cast Total Peter Wright 2311 13.78% 2311 13.78% Kurt Schrader 14389 85.82% 14389 85.82% Mark Callian (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Lassi (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Robert Reynolds (W) 8 0.05% 8 0.05% Pam Marsh (W) 2 0.01% 2 0.01% Clluffy Be Jorn (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Joey Nations (W) 14 0.08% 14 0.08% Mark Callahan (W) 32 0.19% 32 0.19% Shelley Hanson (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Dave McTeague (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Robert L Reynolds 3 0.02% 3 0.02% (W) Andrea Williams (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Erin P Baker (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Dennis Richardson 1 0.01% 1 0.01% (W) Cast Votes: 16767 100.00% 16767 100.00% Undervotes: 1181 1181 Overvotes: 1 1 Unresolved write-in votes: 61 61 Governor - Democratic Party - Vote for one Choice Party Ballots Cast Total Ed Jones 2058 12.09% 2058 12.09% Kate Brown 13303 78.18% 13303 78.18% Candace Neville 1424 8.37% 1424 8.37% Tina Kotek (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Jeff Smith (W) 2 0.01% 2 0.01% Teresa Alonso Leon 1 0.01% 1 0.01% (W) Bud Pierce (W) 2 0.01% 2 0.01% Knute Blum (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Knute Bueler (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Nicholas Parker (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Audrey Broyles (W) 1 0.01% 1 0.01% Unofficial results Cumulative Results Marion County, Oregon Registered Voters Official Election Results May 15, 2018 -

Partisan Federal Election Commission (FEC)

Analysis of H.R. 1 (Part Two) Establishing a Campaign Speech Czar and Enabling Partisan Enforcement: An Altered FEC Structure Poses Risks to First Amendment Speech Rights Bradley A. Smith, Chairman January 2019 Introduction While most of the attention on H.R. 1 has focused on “hot” issues, such as earmarking government subsidies for political campaigns, gerrymandering, and new restrictions on grassroots organizations that engage in public affairs,1 twenty pages of the bill are devoted to the unsexy, yet vitally important, issue of the Federal Election Commission’s (FEC) composition and operating procedures.2 If you’re a Democrat, do you think Donald Trump should be able to appoint a campaign speech czar to determine and en- force the rules on political campaigns? And if you’re a Republican, would you have wanted those rules enforced by a partisan selected by Barack Obama? Of course not. That’s why for over 40 years, Republicans and Democrats have agreed that campaign regulations should be enforced by an independent, bipartisan agency. The Watergate scandal that forced Richard Nixon to resign the presidency showed the dangers of allowing one party to use the power of government against the other.3 As the late Sen. Alan Cranston (D-Ca.) warned during debate on legislation creating the agency, “We must not allow the FEC to become a tool for harassment by future imperial Presidents who may seek to repeat the abuses of Watergate. I un- derstand and share the great concern expressed by some of our colleagues that the FEC has such a potential for abuse in our democratic society that the President should not be given power over the Commission.”4 That concern led to Congressional adoption of the present method of selecting Commission members. -

The 2016 Election, Russian Hackers, And

(DIS)INFORMATION WARFARE: THE 2016 ELECTION, RUSSIAN HACKERS, AND U.S. DEMOCRATIC PRECARITY by EMILY A. FOWLER A THESIS Presented to the Department of Political Science and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Spring 2021 An Abstract of the Thesis of Emily Fowler for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Political Science to be taken Spring 2021 (Dis)information Warfare: The 2016 Election, Russian Hackers, and U.S. Democratic Precarity Approved: ______Daniel Tichenor, Ph.D.__________ Primary Thesis Advisor The 2016 election of Donald J. Trump irrevocably changed the course of American democracy by revealing the malevolent soft power of disinformation warfare in the American electoral system. Russian troll accounts operated by artificial intelligence bots systematically targeted voters on behalf of Mr. Trump to alter behavior and elicit polarizing reactions, cultivating his campaign of fearmongering and racism. Voters of color in key battleground districts—which won Mr. Trump the Electoral College—were marginalized through campaigns slandering Hillary Clinton’s record with Black and Latinx voters. The 2019 special counsel report by Robert Mueller confirmed that Russian disinformation Internet trolls worked to sow discord within the American public in the 2016 election—but what does this reveal about the sustainable future of the United States’ democracy as technology continues evolving? What do these campaigns reveal about the targeted audience for foreign actors and consulting firms? Through my research, I aim to correlate the history of disinformation with the future development of artificial intelligent technologies. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS farm 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) Oregon WoidPcrfect 6.0 Format (Reviled July 199S) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Places Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the informal] property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of signi: Eegories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. historic name MORSE. WAYNE. FARM other names/site number Edgewood Farm; Morse Ranch Park 2/* street & number 595 Crest Drive n/a not for publication city or town Eugene ______ n/a vicinity As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^.nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _x_meets _does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _ nationally _statewide ^c locally. (_jSee continuation sheet for additional comments.) / Deputy SHPO December 22.1998 Signature of certifying official/Title Date Oregon State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property _meets _does not meet the National Register criteria. -

16. a New Kind of First Lady: Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House

fdr4freedoms 1 16. A New Kind of First Lady: Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt at the dedication of a high school in their hometown of Hyde Park, New York, October 5, 1940. Having overcome the shyness that plagued her in youth, ER as First Lady displayed a great appetite for meeting people from all walks of life and learning about their lives and troubles. FDRL Eleanor Roosevelt revolutionized the role of First Lady. No writers; corresponded with thousands of citizens; and served presidential wife had been so outspoken about the nation’s as the administration’s racial conscience. affairs or more hardworking in its causes. ER conveyed to the Although polls at the time of her death in 1962 revealed American people a deep concern for their welfare. In all their ER to be one of the most admired women in the world, not diversity, Americans loved her in return. everyone liked her, especially during her husband’s presidency, When she could have remained aloof or adopted the when those who differed with her strongly held progressive ceremonial role traditional for First Ladies, ER chose to beliefs reviled ER as too forward for a First Lady. She did not immerse herself in all the challenges of the 1930s and ‘40s. shy away from controversy. Her support of a West Virginia She dedicated her tireless spirit to bolstering Americans Subsistence Homestead community spurred debate over against the fear and despair inflicted by the Great Depression the value of communal housing and rural development. By and World War II. -

". . . Politics Is Business. That's What's the Matter with It

". Politics is business. That's what's the matter with it. That's what's the matter with everything,—art, literature, religion, journalism, law, medicine,—they're all business, and all—as you see them." Steffens, The Shame of the Cities (New York, 1957 [1904]), 4. 13. William Allen White, The Old Order Changeth (New York, 1910), 167. 14. Ray Stannard Baker, American Chronicle (New York, 1945), 185. Steffens, The Struggle for Self-Government (New York, 1906), 160. 15. Chapman, Causes and Consequences, 7, 101. Practical Agitation (New York, 1900), 144. Chapman made use of the ideas of the German educator Friedrich Froebel to argue that the growth of the whole man depended upon his creative interaction with others for unselfish ends (Causes, 83-112). Chapman's emphasis on the fundamental bond between creative self- expression and cooperative activity closely paralleled the educational theories of John Dewey and others among the Progressives. Such ideas lent support to the view that individual creativity and disinterestedness were two sides of the same coin. 16. Croly, The Promise of American Life, 22, 103, 411, 417 et passim. 17. Lippmann, A Preface to Politics, 49. 18. Baker, American Chronicle, 183. 19. In discussing the motives for educated, middle-class persons entering settlement work, Jane Addams pointed out that to ignore the struggle against starvation, which was the central element in human history and still occupied at least half the race, deadened one's sympathies and powers of enjoyment and forced one "to live out half the humanity which we have been born heir to and to use but half our faculties." ("The Subjective Necessity for Social Settlements" [1892], reprinted in The Social Thought of Jane Addams, ed. -

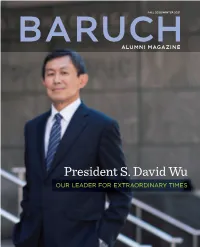

President S. David Wu

FALL 2020/WINTER 2021 BARUCHALUMNI MAGAZINE President S. David Wu OUR LEADER FOR EXTRAORDINARY TIMES MESSAGE FROM FALL 2020/WINTER 2021 THE PRESIDENT IN THIS ISSUE Dear Baruch Alumni, I feel incredibly honored and privileged to join the Baruch community at a pivotal moment in the College’s history. As the nation grapples with the pandemic, the resulting 6 CAMPUS WELCOME Baruch Alumni Magazine economic damage, and the reckoning to end systemic racism, the entire Baruch A Q&A with President S. David Wu: His Vision for Cheryl de Jong–Lambert community unified and overcame unimaginable challenges to continue core College Director of Communications operations and deliver distance learning while supporting our students to keep pace Baruch College and Public Higher Education in the U.S. EDITOR IN CHIEF: Diane Harrigan with their education. I have been impressed not only with Baruch’s remarkable, resilient Baruch’s new president, S. David Wu, PhD, talks personal history, first impressions, and bold initiatives, students, faculty, and staff but with the alumni community. Your welcome has been which include reimagining college education—Baruch style—in the new normal. Says President Wu, SENIOR EDITOR: Gregory M. Leporati genuine and heartfelt, your connection to your alma mater strong, and your appreciation “Baruch shows what is possible at a time when our country desperately needs a more robust and more GRAPHIC DESIGN: Vanguard for the value and impact of your Baruch education has been an inspiration for me. inclusive system of public higher education.” OFFICE OF ALUMNI RELATIONS AND VOLUNTEER ENGAGEMENT My first 100 days were illuminating and productive. -

THE FOLEY REPORT Director’S Update

2018 Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson “Defending the Dreamers” Page 16 THE FOLEY REPORT Director’s Update In 2017 the Cambridge Dictionary chose “populism” as its word of the year. In recent years, movements like the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street thrived, and populist Director Cornell W. Clayton politicians like Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, Sarah 316 Bryan Hall Palin, and Elizabeth Warren have become political stars. Washington State University PO Box 645136 In Europe, Britain voted to leave the EU, populist Cornell Clayton Pullman, WA 99164-5136 politicians like Marine Le Pen in France or Boris Phone 509-335-3477 Johnson in the UK became famous, while Italy, Hungary, Greece and Poland have all elected [email protected] populist governments. foley.wsu.edu Established at Washington State University We are in a populist moment, but what is populism? What explains its growing appeal? And in 1995, the mission of the institute should it concern us? The Foley Institute has hosted several events in recent years exploring is to foster congressional studies, civic various aspects of populist politics, and so I thought I would use my note today to share some education, public service, and public thoughts on this topic. policy research in a non-partisan, cross-disciplinary setting. First, populism is not an ideology that is committed to specific political goals or policies. Rather, it is a style of political discourse or thinking, one which views politics as a conflict Distinguished Professors between corrupt elites (political, economic, intellectual or cultural) and a virtuous “people” Cornell W. Clayton, (the silent majority, the forgotten man, “real” Americans). -

President Harry S Truman's Office Files, 1945–1953

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microforms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT HARRY S TRUMAN’S OFFICE FILES, 1945–1953 Part 2: Correspondence File UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microforms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT HARRY S TRUMAN’S OFFICE FILES, 1945–1953 Part 2: Correspondence File Project Coordinators Gary Hoag Paul Kesaris Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by David W. Loving A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, Maryland 20814-3389 LCCN: 90-956100 Copyright© 1989 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-151-7. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................ v Scope and Content Note ....................................................................................................... xi Source and Editorial Note ..................................................................................................... xiii Reel Index Reel 1 A–Atomic Energy Control Commission, United Nations ......................................... 1 Reel 2 Attlee, Clement R.–Benton, William ........................................................................ 2 Reel 3 Bowles, Chester–Chronological -

Fair Employment, Voting Rights, and Racial Violence (Including Introduction) Timothy N

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass History Publications Dept. of History 2013 Fair Employment, Voting Rights, and Racial Violence (including Introduction) Timothy N. Thurber Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/hist_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Copyright © 2013 by the University Press of Kansas Recommended Citation Thurber, Timothy N. "Fair Employment, Voting Rights, and Racial Violence (including Introduction)" In Republicans and race: the GOP's frayed relationship with African Americans, 1945-1974. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013, Available from VCU Scholars Compass, http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/hist_pubs/8. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Dept. of History at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Republicans and Race The GOP's Frayed Relationship with African Americans, 1945-1974 Timothy N. Thurber o UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KANSAS VIRGINIA COMMONWEALTH UNIVERSITY JK- ~35G .-\ ~B © 2013 by the University Press of Kansas ~O{3 All rights reserved Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thurber, Timothy Nels. Republicans and race: the GOP's frayed relationship with African Americans, 1945-1974/ Timothy N . Thurber. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index.