A Simple Code of Ethics: a History of the Moral Purpose Inspiring Federal Regulation of the Securities Industry John H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mondays 1-3 [email protected] Classroom: William James 303 Office: 237, One Bow Street Office Hours: by Appointment

Instructor: Dr. Ariane Liazos Meeting Time: Mondays 1-3 [email protected] Classroom: William James 303 Office: 237, One Bow Street Office Hours: By appointment Social Studies 68ec: Education and Community in America Universities and Community Engagement, c. 1890-2015 “Life and education must never be separated. We must have more life in our universities, and more education in our life.” 1 !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1 Mary Parker Follett, The New State: Group Organization and the Solution of Popular Government (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1918 [1998]), 369. ! 1 Catalogue Description Explores efforts to realize the civic purpose of American universities, particularly in terms of attempts to engage local communities through educational outreach programs. Examines major periods of experimentation and innovation in the 20th and 21st centuries, from the settlement house movement of the early 1900s to recent efforts to revive the public mission of universities through service-learning and other forms of civic education. This course is an activity-based learning course, limited to students who are concurrently participating in one of PBHA’s education-related service programs. Class discussions and assignments will make active links with students’ service work. Enrollment capped at 12. Course Overview This course explores a variety of attempts of students and faculty to engage their communities in educational programs from the late nineteenth to the early twenty-first centuries. Today, the widely accepted model for university outreach programs is based on the concept of reciprocity: the notion that members of the university and the neighboring community both benefit from their joint endeavors. But this has not always been the case. -

A Conduct-Oriented Approach to the Glass-Steagall Act

Notes A Conduct-Oriented Approach to the Glass-Steagall Act The Glass-Steagall Act' requires that commercial banking be separated from investment banking.2 Courts and regulatory agencies interpreting the prescribed separation often rely on technical and semantic considerations in deciding whether an investment constitutes a "security" for the pur- poses of the Act.' This Note argues that such a "definitional" approach obscures the Act's purposes.4 The Note maintains that the applicable pro- visions of the Act are intended to bar commercial banks from engaging in a particular, identifiable pattern of conduct and that adoption of a "con- duct" test for enforcement of the separation provision would serve the Act's legislative objectives better than the current approach. The Note concludes by applying these alternative approaches to a current Glass- Steagall controversy-the legality of commercial banks' underwriting of commercial paper.' 1. The Glass-Steagall Act is the popular name for the Banking Act of 1933, ch. 89, 48 Stat. 162 (codified in scattered sections of 12 U.S.C.). For a general discussion of the Act, see Perkins, The Divorce of Commercial and Investment Banking. A History, 88 BANKING L.J. 483 (1971). 2. See Banking Act of 1933, §§ 16, 21, 12 U.S.C. §§ 24, 378 (1976). The Banking Act of 1933 contained many provisions of great importance to the banking system, such as those creating the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. The term "Glass-Steagall Act," however, has generally come to refer exclusively to the sections of the Banking Act that pertain to commercial banks' securities activities. -

Lawyers, Bureaucratic Autonomy, and Securities Regulation During the New Deal Daniel R

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2009 Lawyers, Bureaucratic Autonomy, and Securities Regulation During the New Deal Daniel R. Ernst Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/fwps_papers/115 This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/fwps_papers Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Banking and Finance Commons, Corporation and Enterprise Law Commons, Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, Legal History, Theory and Process Commons, and the Securities Law Commons GEORGETOWN LAW Faculty Working Papers September 2009 Lawyers, Bureaucratic Autonomy, and Securities Regulation During the New Deal Daniel R. Ernst Professor of Law Georgetown University Law Center [email protected] This paper can be downloaded without charge from: Scholarly Commons: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/fwps_papers/115/ SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1470934 Posted with permission of the author “I believe in the stock exchanges,” declared the New Deal lawyer Thomas G. Corcoran during a congressional hearing on the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. “I do not believe you should kill them. I do believe you should regulate them–not because I have any social philosophy in regard to the subject–but because as a sheer matter of economic wisdom they should be regulated.” Speaking not long after the Dow Jones Industrial Average had fallen 89 percent and joblessness reached 25 percent, Corcoran charged that unregulated financial markets “have cost many millions of dollars; they have cost 12,000,000 men their jobs.” With the lawyer for the New York Stock Exchange glowering nearby, he defended the bill’s grant of sweeping power to federal administrators. -

Chapter 18: Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1933-1939

Roosevelt and the New Deal 1933–1939 Why It Matters Unlike Herbert Hoover, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was willing to employ deficit spending and greater federal regulation to revive the depressed economy. In response to his requests, Congress passed a host of new programs. Millions of people received relief to alleviate their suffering, but the New Deal did not really end the Depression. It did, however, permanently expand the federal government’s role in providing basic security for citizens. The Impact Today Certain New Deal legislation still carries great importance in American social policy. • The Social Security Act still provides retirement benefits, aid to needy groups, and unemployment and disability insurance. • The National Labor Relations Act still protects the right of workers to unionize. • Safeguards were instituted to help prevent another devastating stock market crash. • The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation still protects bank deposits. The American Republic Since 1877 Video The Chapter 18 video, “Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal,” describes the personal and political challenges Franklin Roosevelt faced as president. 1928 1931 • Franklin Delano • The Empire State Building 1933 Roosevelt elected opens for business • Gold standard abandoned governor of New York • Federal Emergency Relief 1929 Act and Agricultural • Great Depression begins Adjustment Act passed ▲ ▲ Hoover F. Roosevelt ▲ 1929–1933 ▲ 1933–1945 1928 1931 1934 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1930 1931 • Germany’s Nazi Party wins • German unemployment 1933 1928 107 seats in Reichstag reaches 5.6 million • Adolf Hitler appointed • Alexander Fleming German chancellor • Surrealist artist Salvador discovers penicillin Dali paints Persistence • Japan withdraws from of Memory League of Nations 550 In this Ben Shahn mural detail, New Deal planners (at right) design the town of Jersey Homesteads as a home for impoverished immigrants. -

Geographical List of Public Sculpture-1

GEOGRAPHICAL LIST OF SELECTED PERMANENTLY DISPLAYED MAJOR WORKS BY DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH ♦ The following works have been included: Publicly accessible sculpture in parks, public gardens, squares, cemeteries Sculpture that is part of a building’s architecture, or is featured on the exterior of a building, or on the accessible grounds of a building State City Specific Location Title of Work Date CALIFORNIA San Francisco Golden Gate Park, Intersection of John F. THOMAS STARR KING, bronze statue 1888-92 Kennedy and Music Concourse Drives DC Washington Gallaudet College, Kendall Green THOMAS GALLAUDET MEMORIAL; bronze 1885-89 group DC Washington President’s Park, (“The Ellipse”), Executive *FRANCIS DAVIS MILLET AND MAJOR 1912-13 Avenue and Ellipse Drive, at northwest ARCHIBALD BUTT MEMORIAL, marble junction fountain reliefs DC Washington Dupont Circle *ADMIRAL SAMUEL FRANCIS DUPONT 1917-21 MEMORIAL (SEA, WIND and SKY), marble fountain reliefs DC Washington Lincoln Memorial, Lincoln Memorial Circle *ABRAHAM LINCOLN, marble statue 1911-22 NW DC Washington President’s Park South *FIRST DIVISION MEMORIAL (VICTORY), 1921-24 bronze statue GEORGIA Atlanta Norfolk Southern Corporation Plaza, 1200 *SAMUEL SPENCER, bronze statue 1909-10 Peachtree Street NE GEORGIA Savannah Chippewa Square GOVERNOR JAMES EDWARD 1907-10 OGLETHORPE, bronze statue ILLINOIS Chicago Garfield Park Conservatory INDIAN CORN (WOMAN AND BULL), bronze 1893? group !1 State City Specific Location Title of Work Date ILLINOIS Chicago Washington Park, 51st Street and Dr. GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON, bronze 1903-04 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, equestrian replica ILLINOIS Chicago Jackson Park THE REPUBLIC, gilded bronze statue 1915-18 ILLINOIS Chicago East Erie Street Victory (First Division Memorial); bronze 1921-24 reproduction ILLINOIS Danville In front of Federal Courthouse on Vermilion DANVILLE, ILLINOIS FOUNTAIN, by Paul 1913-15 Street Manship designed by D.C. -

16. a New Kind of First Lady: Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House

fdr4freedoms 1 16. A New Kind of First Lady: Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt at the dedication of a high school in their hometown of Hyde Park, New York, October 5, 1940. Having overcome the shyness that plagued her in youth, ER as First Lady displayed a great appetite for meeting people from all walks of life and learning about their lives and troubles. FDRL Eleanor Roosevelt revolutionized the role of First Lady. No writers; corresponded with thousands of citizens; and served presidential wife had been so outspoken about the nation’s as the administration’s racial conscience. affairs or more hardworking in its causes. ER conveyed to the Although polls at the time of her death in 1962 revealed American people a deep concern for their welfare. In all their ER to be one of the most admired women in the world, not diversity, Americans loved her in return. everyone liked her, especially during her husband’s presidency, When she could have remained aloof or adopted the when those who differed with her strongly held progressive ceremonial role traditional for First Ladies, ER chose to beliefs reviled ER as too forward for a First Lady. She did not immerse herself in all the challenges of the 1930s and ‘40s. shy away from controversy. Her support of a West Virginia She dedicated her tireless spirit to bolstering Americans Subsistence Homestead community spurred debate over against the fear and despair inflicted by the Great Depression the value of communal housing and rural development. By and World War II. -

William Augustus Muhlenberg and Phillips Brooks and the Growth of the Episcopal Broad Church Movement

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 Parties, Visionaries, Innovations: William Augustus Muhlenberg and Phillips Brooks and the Growth of the Episcopal Broad Church Movement Jay Stanlee Frank Blossom College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Blossom, Jay Stanlee Frank, "Parties, Visionaries, Innovations: William Augustus Muhlenberg and Phillips Brooks and the Growth of the Episcopal Broad Church Movement" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625924. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-x318-0625 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. P a r t ie s , V i s i o n a r i e s , I n n o v a t i o n s William Augustus Muhlenberg and Phillips Brooks and the Growth of the Episcopal Broad Church Movement A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts hy Jay S. F. Blossom 1994 Ap p r o v a l S h e e t This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Jay S. -

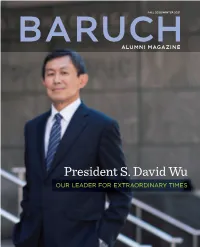

President S. David Wu

FALL 2020/WINTER 2021 BARUCHALUMNI MAGAZINE President S. David Wu OUR LEADER FOR EXTRAORDINARY TIMES MESSAGE FROM FALL 2020/WINTER 2021 THE PRESIDENT IN THIS ISSUE Dear Baruch Alumni, I feel incredibly honored and privileged to join the Baruch community at a pivotal moment in the College’s history. As the nation grapples with the pandemic, the resulting 6 CAMPUS WELCOME Baruch Alumni Magazine economic damage, and the reckoning to end systemic racism, the entire Baruch A Q&A with President S. David Wu: His Vision for Cheryl de Jong–Lambert community unified and overcame unimaginable challenges to continue core College Director of Communications operations and deliver distance learning while supporting our students to keep pace Baruch College and Public Higher Education in the U.S. EDITOR IN CHIEF: Diane Harrigan with their education. I have been impressed not only with Baruch’s remarkable, resilient Baruch’s new president, S. David Wu, PhD, talks personal history, first impressions, and bold initiatives, students, faculty, and staff but with the alumni community. Your welcome has been which include reimagining college education—Baruch style—in the new normal. Says President Wu, SENIOR EDITOR: Gregory M. Leporati genuine and heartfelt, your connection to your alma mater strong, and your appreciation “Baruch shows what is possible at a time when our country desperately needs a more robust and more GRAPHIC DESIGN: Vanguard for the value and impact of your Baruch education has been an inspiration for me. inclusive system of public higher education.” OFFICE OF ALUMNI RELATIONS AND VOLUNTEER ENGAGEMENT My first 100 days were illuminating and productive. -

Securities Exchange Act - Cooperative

Duquesne Law Review Volume 29 Number 4 Article 11 1991 Securities Regulation - Securities Exchange Act - Cooperative Christine Ita McGonigle Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Christine I. McGonigle, Securities Regulation - Securities Exchange Act - Cooperative, 29 Duq. L. Rev. 853 (1991). Available at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr/vol29/iss4/11 This Recent Decision is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Duquesne Law Review by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. SECURITIES REGULATION-SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT-COOPERATIvE-Uncollateralized, unsecured demand notes sold as an investment vehicle fall within both the "note" and "se- curity" categories of section 3(a)(10)of the Securities Exchange Act. Reves v Ernst & Young,-US-, 110 S Ct 945, 948 (1990). The Farmers Cooperative of Arkansas and Oklahoma, Inc. (here- inafter, "Co-op") obtained a portion of its general business operat- ing funds from the sale of uncollateralized, uninsured demand promissory notes.' The notes were sold on an ongoing basis to both Co-op members and nonmembers.2 Marketed as an investment de- vice, the notes paid a variable rate of interest higher than that which was paid by local financial institutions.3 No financial infor- mation regarding the Co-op was released to the purchasers except a statement of the Co-op's total assets, which was released periodically.4 Arthur Young5 was engaged by the Co-op to audit and report on the Co-op's 1981 and 1982 financial statements.6 The audited fi- nancial statements were not publicly released. -

The Origins of the Securities Laws

INSTITUTIONAL INVESTOR Bernstein Litowitz Berger & Grossmann LLP AdvocateECURITIES RAUD AND ORPORATE A S F C G OVERNANCE Q UARTERLY Fourth Quarter 2004 THE ORIGINS OF THE SECURITIES LAWS The Origins of the By Norman S. Poser Securities Laws The corporate abuses that have come to light during the past few years are not unprecedented. 1 Similar events led to the enactment of the federal securities laws seventy years ago. I have been Inside Look asked to tell you something about the human side of these laws: the remarkable people who were present at their birth and who nursed 2 them during their early days. When Franklin D. Roosevelt took office on Eye On The Issues March 4, 1933, the country was in the depth of the worst Depression in its history. Thirteen million 6 people, representing 25 percent of the work force, were unemployed — 800,000 in New York alone. Foreclosures of farms throughout the Quarterly Quote country, long lines at soup kitchens in the cities and towns, business and bank failures were signs as well as causes of the general despair.1 Norman S. Poser, Professor of Law, 10 Brooklyn Law School. Professor Poser The Great Crash of 1929 and its aftermath, was a featured speaker at BLB&G’s which had wiped out 83 percent of the value of 10th Institutional Investor Forum. the stocks listed on the New York Stock Save the Date! Exchange, was still fresh in people’s minds. scandals that led to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. The next BLB&G Many believed that corporate and stock market Institutional Investor Securities reform was high on the list of abuses had caused the Crash and that the Crash Forum will be in NYC measures contained in Roosevelt’s New Deal on Oct. -

President Harry S Truman's Office Files, 1945–1953

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microforms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT HARRY S TRUMAN’S OFFICE FILES, 1945–1953 Part 2: Correspondence File UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microforms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg PRESIDENT HARRY S TRUMAN’S OFFICE FILES, 1945–1953 Part 2: Correspondence File Project Coordinators Gary Hoag Paul Kesaris Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by David W. Loving A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, Maryland 20814-3389 LCCN: 90-956100 Copyright© 1989 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-151-7. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................ v Scope and Content Note ....................................................................................................... xi Source and Editorial Note ..................................................................................................... xiii Reel Index Reel 1 A–Atomic Energy Control Commission, United Nations ......................................... 1 Reel 2 Attlee, Clement R.–Benton, William ........................................................................ 2 Reel 3 Bowles, Chester–Chronological -

Eleanor Roosevelt and the Arthurdale Subsistence Housing Project

Volume 4, Issue No. 1. Turning Coal to Diamond: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Arthurdale Subsistence Housing Project Renée Trepagnier Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA ÒÏ Abstract: In 1933, Eleanor Roosevelt (ER), the First Lady of the United States, initiated a subsistence housing project, Arthurdale, funded by the federal government to help a poor coal mining town in West Virginia rise above poverty. ER spotlighted subsistence housing as a promising venture for poor American workers to develop economic stability and community unification. She encountered harsh pushback from the federal government, the American public, and private industries. Deemed communistic and excessively expensive, Arthrudale pushed the boundaries of federal government involvement in community organization. Bureaucratic and financial issues impacted the community’s employment rates, income, and community cooperation. ER persisted, perhaps too blindly, until the federal government declared the project a failure and pulled out to avoid further financial loses. ER’s involvement in Arthurdale’s administration and bureaucracy radically shifted the role of the First Lady, a position with no named responsibilities or regulations. Before ER, First Ladies never exercised authority in federally regulated projects and rarely publicly presented their opinions. Did ER’s involvement in Arthurdale hinder or promote the project’s success? Should a First Lady involve herself in federal policy? If so, how much authority should she possess? “Nothing we do in this world is ever wasted and I have come to the conclusion that practically nothing we ever do stands by itself. If it is good, it will serve some good purpose in the future. If it is evil, it may haunt us and handicap our efforts in unimagined ways” –Eleanor Roosevelt 1961 Crushing Poverty in West Virginia In the mid to late 19th century, industrialization developed in the United States, necessitating a demand for coal.