The Arabic Hour: Understanding Arab-American Media Activism and Community-Based Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamas: Background and Issues for Congress

Hamas: Background and Issues for Congress December 2, 2010 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R41514 Hamas: Background and Issues for Congress Summary This report and its appendixes provide background information on Hamas, or the Islamic Resistance Movement, and U.S. policy towards it. It also includes information and analysis on (1) the threats Hamas currently poses to U.S. interests, (2) how Hamas compares with other Middle East terrorist groups, (3) Hamas’s ideology and policies (both generally and on discrete issues), (4) its leadership and organization, and (5) its sources of assistance. Finally, the report raises and discusses various legislative and oversight options related to foreign aid strategies, financial sanctions, and regional and international political approaches. In evaluating these options, Congress can assess how Hamas has emerged and adapted over time, and also scrutinize the track record of U.S., Israeli, and international policy to counter Hamas. Hamas is a Palestinian Islamist military and sociopolitical movement that grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood. The United States, Israel, the European Union, and Canada consider Hamas a terrorist organization because of (1) its violent resistance to what it deems Israeli occupation of historic Palestine (constituting present-day Israel, West Bank, and Gaza Strip), and (2) its rejection of the off-and-on peace process involving Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) since the early 1990s. Since Hamas’s inception in 1987, it has maintained its primary base of political support and its military command in the Gaza Strip—a territory it has controlled since June 2007—while also having a significant presence in the West Bank. -

News of Terrorism and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center News of Terrorism and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict (September 1-6, 2010) Hamas spokesman Musheir al-Masri extols the terrorist shooting attack in Judea and Samaria (Al-Jazeera TV, August 31, 2010). Overview This past week events focused on the relaunching of the direct talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority in Washington. According to media reports, both sides agreed their objective was to formulate a "framework agreement" within a year which would define the principles of a resolution for the conflict and the establishment of a Palestinian state. George Mitchell, the American envoy to the Middle East, said that Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu and Palestinian Authority Chairman Mahmoud Abbas had also agreed to meet in the Middle East on September 14 and 15, and that they would continue meeting every two weeks. The opening session was accompanied by shootin g attacks carried out by Hamas and targeting Israeli vehicles in Judea and Samaria: An attack southeast of Hebron killed four Israeli civilians. In another shooting attack in eastern Samaria two Israeli civilians were wounded. A shooting attack northeast of Ramallah did not result in casualties. Responsibility for the attacks, which were intended to disrupt 248-10 the relaunching of the talks, was claimed by Hamas, which also threatened to maintain a dialogue with Israel "with guns." 2 Important Terrorist Events Shooting Attacks in Judea and Samaria On the evening of August 31 an Israeli vehicle was shot at near the Bani Naim junction southeast of Kiryat Arba in Judea. The four Israeli civilians in the car were killed. -

Race and Transnationalism in the First Syrian-American Community, 1890-1930

Abstract Title of Thesis: RACE ACROSS BORDERS: RACE AND TRANSNATIONALISM IN THE FIRST SYRIAN-AMERICAN COMMUNITY, 1890-1930 Zeinab Emad Abrahim, Master of Arts, 2013 Thesis Directed By: Professor, Madeline Zilfi Department of History This research explores the transnational nature of the citizenship campaign amongst the first Syrian Americans, by analyzing the communication between Syrians in the United States with Syrians in the Middle East, primarily Jurji Zaydan, a Middle-Eastern anthropologist and literary figure. The goal is to demonstrate that while Syrian Americans negotiated their racial identity in the United States in order to attain the right to naturalize, they did so within a transnational framework. Placing the Syrian citizenship struggle in a larger context brings to light many issues regarding national and racial identity in both the United States and the Middle East during the turn of the twentieth century. RACE ACROSS BORDERS: RACE AND TRANSNATIONALISM IN THE FIRST SYRIAN-AMERICAN COMMUNITY, 1890-1930 by Zeinab Emad Abrahim Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts 2013 Advisory Committee: Professor, Madeline Zilfi, Chair Professor, David Freund Professor, Peter Wien © Copyright by Zeinab Emad Abrahim 2013 For Mahmud, Emad, and Iman ii Table of Contents List of Images…………………………………………………………………....iv Introduction………………………………………………………………………1-12 Chapter 1: Historical Contextualization………………………………………13-25 -

Download Book

Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics American Literature Readings in the 21st Century Series Editor: Linda Wagner-Martin American Literature Readings in the 21st Century publishes works by contemporary critics that help shape critical opinion regarding literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the United States. Published by Palgrave Macmillan Freak Shows in Modern American Imagination: Constructing the Damaged Body from Willa Cather to Truman Capote By Thomas Fahy Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics By Steven Salaita Women and Race in Contemporary U.S. Writing: From Faulkner to Morrison By Kelly Lynch Reames Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics Steven Salaita ARAB AMERICAN LITERARY FICTIONS, CULTURES, AND POLITICS © Steven Salaita, 2007. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2007 978-1-4039-7620-8 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-53687-0 ISBN 978-0-230-60337-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230603370 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. -

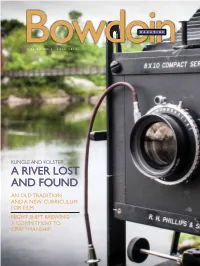

2012-Fall.Pdf

MAGAZINE BowdoiVOL.84 NO.1 FALL 2012 n KLINGLE AND KOLSTER A RIVER LOST AND FOUND AN OLD TRADITION AND A NEW CURRICULUM FOR FILM NIGHT SHIFT BREWING: A COMMITMENT TO CRAFTMANSHIP FALL 2012 BowdoinMAGAZINE CONTENTS 14 A River Lost and Found BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM PHOTOGRAPHS BY BRIAN WEDGE ’97 AND MIKE KOLSTER Ed Beem talks to Professors Klingle and Kolster about their collaborative multimedia project telling the story of the Androscoggin River through photographs, oral histories, archival research, video, and creative writing. 24 Speaking the Language of Film "9,)3!7%3%,s0(/4/'2!0(3"9-)#(%,%34!0,%4/. An old tradition and a new curriculum combine to create an environment for film studies to flourish at Bowdoin. 32 Working the Night Shift "9)!.!,$2)#(s0(/4/'2!0(3"90!40)!3%#+) After careful research, many a long night brewing batches of beer, and with a last leap of faith, Rob Burns ’07, Michael Oxton ’07, and their business partner Mike O’Mara, have themselves a brewery. DEPARTMENTS Bookshelf 3 Class News 41 Mailbox 6 Weddings 78 Bowdoinsider 10 Obituaries 91 Alumnotes 40 Whispering Pines 124 [email protected] 1 |letter| Bowdoin FROM THE EDITOR MAGAZINE Happy Accidents Volume 84, Number 1 I live in Topsham, on the bank of the Androscoggin River. Our property is a Fall 2012 long and narrow lot that stretches from the road down the hill to our house, MAGAZINE STAFF then further down the hill, through a low area that often floods when the tide is Editor high, all the way to the water. -

The Mystical Element in Mikhall Lku6aymah's Litesary Works and Its Affinity to Islamic Mysticism

The Mystical Element in Mikhall lKu6aymah's Litesary Works and Its Affinity to Islamic Mysticism BY Yeni Ratna Yuuingsib, A thesis submitted to the Facul* of Graduate Studies and Research in partial ialflllment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Institute of Islamic Studies MCGLU University Montreal June 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 ofCanada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Strmt 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation, ABSTRACT Author : Yeni Ratna Yuningsih Title : The Mystical Element in MikhaU Nucaymah's Literary Works and Its AfEmity to Islamic Mysticism Department : Institute of Islamic Studies Degree : Master of Arts This thesis investigates the mystical elements in MikhS'ïl Nu'ayrnah's literary works and their affiity to Islamic mysticisrn, elaborating in particular on the notions of oneness of being and the transmigration of soul. -

Former Ottomans in the Ranks: Pro-Entente Military Recruitment Among Syrians in the Americas, 1916–18*

Journal of Global History (2016), 11,pp.88–112 © Cambridge University Press 2016 doi:10.1017/S1740022815000364 Former Ottomans in the ranks: pro-Entente military recruitment among Syrians in the Americas, 1916–18* Stacy D. Fahrenthold Center for Middle Eastern Studies, University of California, Berkeley, California, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract For half a million ‘Syrian’ Ottoman subjects living outside the empire, the First World War initiated a massive political rift with Istanbul. Beginning in 1916, Syrian and Lebanese emigrants from both North and South America sought to enlist, recruit, and conscript immigrant men into the militaries of the Entente. Employing press items, correspondence, and memoirs written by émigré recruiters during the war, this article reconstructs the transnational networks that facilitated the voluntary enlistment of an estimated 10,000 Syrian emigrants into the armies of the Entente, particularly the United States Army after 1917. As Ottoman nationals, many Syrian recruits used this as a practical means of obtaining American citizen- ship and shedding their legal ties to Istanbul. Émigré recruiters folded their military service into broader goals for ‘Syrian’ and ‘Lebanese’ national liberation under the auspices of American political support. Keywords First World War, Lebanon, mobilization, Syria, transnationalism Is it often said that the First World War was a time of unprecedented military mobilization. Between 1914 and 1918, empires around the world imposed powers of conscription on their -

Representation of the Arab Exile in Arab American Literature

El Mawrouth Review Vol: 08. / Issuem 01 S :( /2020), p 70-81 Representation of the Arab Exile in Arab American Literature Faiza Hairech Abdel Hamid Ibn Badis University of Mostaganem [email protected] Received: 08/10/2019 Accepted: 27/01/2020 Published 13/08/2020 Abstract: Exile, as a state of being, harks back to the existence of humankind, as natural misfortunes were the very first reasons behind one's displacement in their quest for survival. Exiles could be viewed as a state of those who were obliged to flee their homelands due to political persecutions; economic issues as well as religious clashes. The exiles focused upon in this paper are Arabs. This humble research attempts to track the representation of Arab American exiles in Arab American literature, from El Mahjar to post-9/11 literature. The approach this paper relies upon is a postcolonial reading. Arab exiles’ representation in Arab American literature varies from that of devout nationalists and cultural mediators to literary militants, having as a mission to free the Arab psyche from the guilt of terrorism that torments it. Keywords: Arab American literature; diaspora; exile; minor literature; representation. 11 . Corresponding author: Faiza Hairech, e-mail: [email protected] 70 Representation of the Arab Exile in Arab American Literature 1. INTRODUCTION Arab American literature, as recently over spotlighted area of study, tackles several themes that are tightly related to the status quo of the Arab world in general and the current Arab American landscape in particular. Homesickness, nationalism, Terrorism, Islamism, exile, and diaspora are the recurrent themes tackled by Arab American writers. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

How Norms and Pathways Have Developed Phd Th

European civil actors for Palestinian rights and a Palestinian globalized movement: How norms and pathways have developed PhD Thesis (Erasmusmundus GEM Joint Doctorate in Political and Social Sciences from Université Libre de Bruxelles _ ULB- & Political Science and Theory from LUISS Guido Carli University, Rome) By Amro SADELDEEN Thesis advisors: Pr. Jihane SFEIR (ULB) Pr. Francesca CORRAO (Luiss) Academic Year 2015-2016 1 2 Contents Abbreviations, p. 5 List of Figures and tables, p. 7 Acknowledgement, p.8 Chapter I: Introduction, p. 9 1. Background and introducing the research, p. 9 2. Introducing the case, puzzle and questions, p. 12 3. Thesis design, p. 19 Chapter II: Theories and Methodologies, p. 22 1. The developed models by Sikkink et al., p. 22 2. Models developed by Tarrow et al., p. 25 3. The question of Agency vs. structure, p. 29 4. Adding the question of culture, p. 33 5. Benefiting from Pierre Bourdieu, p. 34 6. Methodology, p. 39 A. Abductive methodology, p. 39 B. The case; its components and extension, p. 41 C. Mobilizing Bourdieu, TSM theories and limitations, p. 47 Chapter III: Habitus of Palestinian actors, p. 60 1. Historical waves of boycott, p. 61 2. The example of Gabi Baramki, p. 79 3. Politicized social movements and coalition building, p. 83 4. Aspects of the cultural capital in trajectories, p. 102 5. The Habitus in relation to South Africa, p. 112 Chapter IV: Relations in the field of power in Palestine, p. 117 1. The Oslo Agreement Period, p. 118 2. The 1996 and 1998 confrontations, p. -

ARABI E MUSULMANI D'america Scompigliare Le Carte Della

ARABI E MUSULMANI D’AMERICA Scompigliare le carte della letteratura arabo-americana: un’analisi di gender e di genre Lisa Marchi* Quando nel 1999 Judith Butler pubblica negli Stati Uniti Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, si dichiara sicura di voler produrre “un ‘intervento’ provocatorio nella teoria femminista”1 con l’intento non di restringere, ma piutto- sto di ampliare il significato stesso di genere. È così che per intervento di Butler il genere diventa un trouble, vale a dire non una semplice categoria identitaria, né una mera questione aperta, ma piuttosto un guaio, una confusione, un fastidio- so e urticante disturbo che scompiglia il cosiddetto ordine naturale delle cose. È allo spirito provocatorio di Butler che guardo, mentre mi accingo a intervenire da una prospettiva di genere sulla traiettoria, tradizionalmente lineare e trionfa- listica, della storia della migrazione arabo-americana e della letteratura prodotta a partire da quell’esperienza migratoria. Qualcuno potrebbe chiedersi perché si renda necessario oggi rileggere la storia della migrazione e della letteratura ara- bo-americana proprio a partire dal libro di una teorica femminista statunitense ebrea. Ricordo che Butler, oltre a essere un’importante filosofa, è anche un’ebrea impegnata nell’attivismo politico. I suoi scritti e prese di posizione politiche per il riconoscimento del popolo palestinese, e più in generale per la realizzazione di una comunità politica globale più giusta, hanno prodotto delle trasformazioni radicali nel nostro modo -

Atavism and Modernity in Time's Portrayal of the Arab World, 2001-2011

Atavism and Modernity in Time's Portrayal of the Arab World, 2001-2011 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Mary R. Abowd August 2013 © 2013 Mary R. Abowd. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled Atavism and Modernity in Time's Portrayal of the Arab World, 2001-2011 by MARY R. ABOWD has been approved for the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism and the Scripps College of Communication by Anne Cooper Professor Emerita of Journalism Scott Titsworth Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT ABOWD, MARY R., Ph.D., August 2013, Journalism Atavism and Modernity in Time's Portrayal of the Arab World, 2001-2011 Director of Dissertation: Anne Cooper This study builds on research that has documented the persistence of negative stereotypes of Arabs and the Arab world in the U.S. media during more than a century. The specific focus is Time magazine’s portrayal of Arabs and their societies between 2001 and 2011, a period that includes the September 11, 2001, attacks; the ensuing U.S.- led “war on terror;” and the mass “Arab Spring” uprisings that spread across the Arab world beginning in late 2010. Using a mixed-methods approach, the study explores whether and to what extent Time’s coverage employs what Said (1978) called Orientalism, a powerful binary between the West and the Orient characterized by a consistent portrayal of the West as superior—rational, ordered, cultured—and the Orient as its opposite—irrational, chaotic, depraved.