FULLTEXT02.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KIA Language Framework

KIA Language Framework Revitalizing Inuit Language in the Qitirmiut Region - Final Report - RT Associates August 2011 KIA Language Framework Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ i 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 2 Background................................................................................................................... 4 3 Qitirmiut Language Landscape ................................................................................. 11 4 Lessons from Other Jurisdictions .............................................................................. 16 5 What People Told Us.................................................................................................. 22 6 Analysis & Recommendations .................................................................................. 28 7 KIA Language Framework ......................................................................................... 31 Note to the Reader: We have used the term ‘Inuit Language’ to refer to the different Inuit language dialects used throughout the Qitirmiut Region including Innuinaqtun in the West communities and Nattilingmiutut in the East communities. RT Associates August 2011 KIA Language Framework Executive Summary Executive Summary Introduction In January 2011 KIA contracted consultants (RT Associates) to develop a KIA Language -

Remedial Action Plan, Former Metal Dump and Community Landfill

Public Works and Government Services Canada on behalf of Transport Canada REMEDIAL ACTION PLAN, FORMER METAL DUMP AND COMMUNITY LANDFILL Iqaluit, Nunavut 27 January 2017 REMEDIAL ACTION PLAN, FORMER METAL DUMP AND COMMUNITY LANDFILL REMEDIAL ACTION PLAN, FORMER METAL DUMP AND COMMUNITY LANDFILL Transport Canada (Custodian) Steve Livingstone, M.Sc., P.Geo. Prepared for: Project Director Michael Brownlee, Sr. Environmental Specialist Public Works and Government Services Canada 10025 Jasper Avenue, Edmonton, Alberta T5J 1S6 Prepared by: Ryan Fletcher, C. Tech, CEPIT 329 Churchill Avenue North, Suite 200 Sr. Environmental Technician Ottawa, Ontario K1Z 5B8 Tel 613 721 0555 Fax 613 721 0029 Our Ref.: Caroline Béland-Pelletier, M.Sc., P.Eng., PMP 102153-000 Sr. Contaminant Hydrogeologist Date: 27 January 2017 This document is intended only for the use of the individual or entity for which it was prepared and may contain information that is privileged, confidential and exempt from disclosure under applicable law. Any dissemination, distribution or copying of this document is strictly prohibited. arcadis.com z:\projects\2016\102153-000 tc iqaluit\rap update\rap iqaluit former metal community dump_final_20170127.docx REMEDIAL ACTION PLAN, FORMER METAL DUMP AND COMMUNITY LANDFILL VERSION CONTROL Issue Revision No Date Issued Description Reviewed by 1 0 2016-12-15 Draft SL 2 0 2017-01-27 Final SL arcadis.com z:\projects\2016\102153-000 tc iqaluit\rap update\rap iqaluit former metal community dump_final_20170127.docx REMEDIAL ACTION PLAN, FORMER -

April 27, 2000

Nunavut Canada LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF NUNAVUT 3rd Session 1st Assembly HANSARD Official Report DAY 42 Thursday, April 27, 2000 Pages 1908 - 1976 Iqaluit Speaker: The Hon. Kevin O’Brien, M.L.A. Legislative Assembly of Nunavut Speaker Hon. Kevin O’Brien (Arviat) Ovide Alakannuark Hon. Ed Picco Hon. Jack Anawak (Akulliq) (Iqaluit East) (Rankin Inlet North) Minister of Health and Social Minister of Justice; Minister of Enoki Irqittuq Services; Minister Nunavut Community Government and (Amittuq) Power Corporation Transportation Deputy Chair, Committee of the Whole Hon. Paul Okalik Hon. Manitok Thompson (Iqaluit West) (Rankin Inlet South-Whale Uriash Puqiqnak Premier; Minister of Executive Cove) (Nattilik) and Intergovernmental Affairs Minister of Housing; Minister of Deputy Speaker Public Works, Hon. Donald Havioyak Telecommunications and Glenn McLean (Kugluktuk) Technical Services (Baker Lake) Hon. James Arvaluk Olayuk Akesuk Hon. Kelvin Ng (Nanulik) (South Baffin) (Cambridge Bay) Minister of Education Deputy Premier; Minister of Jobie Nutarak Finance and Administration; Levi Barnabas (Tunnuniq) Minister of Human Resources; (Quttiktuq) Government House Leader David Iqaqrialu Hon. Peter Kilabuk (Uqqummiut) Hon. Peter Kattuk (Pangnirtung) Deputy Chair, Committee of the (Hudson Bay) Minister of Sustainable Whole Development Hunter Tootoo (Iqaluit Centre) Officers Clerk John Quirke Deputy Clerk Clerk of Committees Law Clerk Sergeant-At-Arms Editors of Hansard Rhoda Perkison Nancy Tupik Susan Cooper Jaco Ishulutak Innirvik Support Services Box -

Figure 5: Arctic Bay and Clyde River Site-Specific Marine Hunting Values Reported in the Study Area

FINAL REPORT: QIA’S TUSAQTAVUT STUDY SPECIFIC TO BAFFINLAND’S PROPOSED PHASE 2 OF THE MARY RIVER PROJECT FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF ARCTIC BAY AND CLYDE RIVER Figure 5: Arctic Bay and Clyde River site-specific Marine Hunting values reported in the Study Area 37 FINAL REPORT: QIA’S TUSAQTAVUT STUDY SPECIFIC TO BAFFINLAND’S PROPOSED PHASE 2 OF THE MARY RIVER PROJECT FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF ARCTIC BAY AND CLYDE RIVER 4.2.2 Importance Marine Hunting encompasses a variety of species, bodies of knowledge, modes of travel, animal processing and food storage techniques (e.g., food caches), and harvesting locations and habitation sites. Study participants have used and continue to use the Study Area for Marine Hunting. The quotes below highlight some of their experiences hunting narwhal, walrus, and seal species in and around Milne Inlet, Eclipse Sound, Pond Inlet, and Baffin Bay. So, his family would also go narwhal hunting around Milne Inlet. … Yeah, that was a prime narwhal hunting area all that along here. … Yeah, that whole area. (C15 2020a, interpreted from Inuktitut) There was so much narwhal that you could hear them as soon as you wake up and they’d be there all day … They’re migrating but there’s so many of them that they would – it could take all day into the night, that’s how much narwhal there was … So they … would do all their narwhal hunting around that area [in Eclipse Sound]. (A01 2020, interpreted from Inuktitut) Plenty of seal hunting around Mount Herodier area. … And then, you know, he would also remember people catching narwhal really close to Pond Inlet when he was a child, but he can’t quite pinpoint what the year was. -

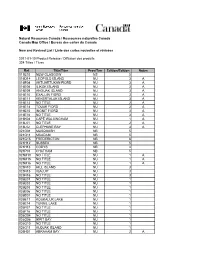

20110110 CMO Maps

Natural Resources Canada / Ressources naturelles Canada Canada Map Office / Bureau des cartes du Canada New and Revised List / Liste des cartes nouvelles et révisées 2011-01-10 Product Release / Diffusion des produits 324 Titles / Titres Ref. Title/Titre Prov/Terr Edition/Édition Notes 011E10 NEW GLASGOW NS 5 016D14 LEOPOLD ISLAND NU 3 A 016E04 AKTIJARTUKAN FIORD NU 3 A 016E06 ILIKOK ISLAND NU 3 A 016E09 ANGIJAK ISLAND NU 3 A 016E10 EXALUIN FIORD NU 3 A 016E11 KEKERTALUK ISLAND NU 3 A 016E13 NO TITLE NU 2 A 016E14 TOUAK FIORD NU 2 A 016E15 INGNIT FIORD NU 3 A 016E16 NO TITLE NU 3 A 016K04 CAPE WALSINGHAM NU 1 A 016L01 NO TITLE NU 2 A 016L02 CLEPHANE BAY NU 3 A 021G01 MUSQUASH NB 5 021G11 MCADAM NB 5 021G15 FREDERICTON NB 6 021H12 SUSSEX NB 5 021H13 CODYS NB 4 021P03 CHATHAM NB 5 025M10 NO TITLE NU 1 A 025M15 NO TITLE NU 1 A 025M16 NO TITLE NU 1 A 025N10 HILL ISLAND NU 3 025N15 IQALUIT NU 3 025N16 NO TITLE NU 3 026E01 NO TITLE NU 1 026E02 NO TITLE NU 1 026E03 NO TITLE NU 1 026E06 NO TITLE NU 1 026E07 NO TITLE NU 1 026E11 KOUKALUK LAKE NU 1 026E14 TUNNIL LAKE NU 1 026F07 NO TITLE NU 1 026F16 NO TITLE NU 1 026G04 NO TITLE NU 1 026G06 IKPIT BAY NU 1 026G10 NO TITLE NU 1 026G11 KUDJAK ISLAND NU 1 026H01 ABRAHAM BAY NU 2 A 026H02 QUEENS CAPE NU 2 A 026H06 SHOMEO POINT NU 2 A 026H07 KUMLIEN FIORD NU 2 A 026H08 UJUKTUK FIORD NU 2 A 026H10 NO TITLE NU 2 A 026H11 IQALUJJUAQ FIORD NU 2 A 026H12 KEKERTEN ISLAND NU 2 A 026H13 KEKERTUKDJUAK ISLAND NU 2 A 026H14 NO TITLE NU 2 A 026I03 KINGNAIT HARBOUR NU 2 A 026I04 PANGNIRTUNG NU 2 A 026I05 MOON PEAK -

Vessel Operation Restriction Regulations Règlement Sur Les Restrictions Visant L’Utilisation Des Bâtiments

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Vessel Operation Restriction Règlement sur les restrictions Regulations visant l’utilisation des bâtiments SOR/2008-120 DORS/2008-120 Current to June 20, 2019 À jour au 20 juin 2019 Last amended on October 10, 2018 Dernière modification le 10 octobre 2018 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

Canadian Arctic Tide Measurement Techniques and Results

International Hydrographie Review, Monaco, LXIII (2), July 1986 CANADIAN ARCTIC TIDE MEASUREMENT TECHNIQUES AND RESULTS by B.J. TAIT, S.T. GRANT, D. St.-JACQUES and F. STEPHENSON (*) ABSTRACT About 10 years ago the Canadian Hydrographic Service recognized the need for a planned approach to completing tide and current surveys of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago in order to meet the requirements of marine shipping and construction industries as well as the needs of environmental studies related to resource development. Therefore, a program of tidal surveys was begun which has resulted in a data base of tidal records covering most of the Archipelago. In this paper the problems faced by tidal surveyors and others working in the harsh Arctic environment are described and the variety of equipment and techniques developed for short, medium and long-term deployments are reported. The tidal characteris tics throughout the Archipelago, determined primarily from these surveys, are briefly summarized. It was also recognized that there would be a need for real time tidal data by engineers, surveyors and mariners. Since the existing permanent tide gauges in the Arctic do not have this capability, a project was started in the early 1980’s to develop and construct a new permanent gauging system. The first of these gauges was constructed during the summer of 1985 and is described. INTRODUCTION The Canadian Arctic Archipelago shown in Figure 1 is a large group of islands north of the mainland of Canada bounded on the west by the Beaufort Sea, on the north by the Arctic Ocean and on the east by Davis Strait, Baffin Bay and Greenland and split through the middle by Parry Channel which constitutes most of the famous North West Passage. -

March 9, 2021

NUNAVUT HANSARD UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT TUESDAY, MARCH 9, 2021 IQALUIT, NUNAVUT Hansard is not a verbatim transcript of the debates of the House. It is a transcript in extenso. In the case of repetition or for a number of other reasons, such as more specific identification, it is acceptable to make changes so that anyone reading Hansard will get the meaning of what was said. Those who edit Hansard have an obligation to make a sentence more readable since there is a difference between the spoken and the written word. Debates, September 20, 1983, p. 27299. Beauchesne’s 6th edition, citation 55 Corrections: PLEASE RETURN ANY CORRECTIONS TO THE CLERK OR DEPUTY CLERK Legislative Assembly of Nunavut Speaker Hon. Paul Quassa (Aggu) Hon. David Akeeagok Joelie Kaernerk David Qamaniq (Quttiktuq) (Amittuq) (Tununiq) Deputy Premier; Minister of Economic Development and Transportation; Minister Pauloosie Keyootak Emiliano Qirngnuq of Human Resources (Uqqummiut) (Netsilik) Tony Akoak Hon. Lorne Kusugak Allan Rumbolt (Gjoa Haven) (Rankin Inlet South) (Hudson Bay) Deputy Chair, Committee of the Whole Minister of Health; Minister Deputy Speaker and Chair of the responsible for Seniors; Minister Committee of the Whole Pat Angnakak responsible for Suicide Prevention (Iqaluit-Niaqunnguu) Hon. Joe Savikataaq Deputy Chair, Committee of the Whole Adam Lightstone (Arviat South) (Iqaluit-Manirajak) Premier; Minister of Executive and Hon. Jeannie Ehaloak Intergovernmental Affairs; Minister of (Cambridge Bay) John Main Energy; Minister of Environment; Minister of Community and Government (Arviat North-Whale Cove) Minister responsible for Immigration; Services; Minister responsible for the Qulliq Minister responsible for Indigenous Hon. Margaret Nakashuk Energy Corporation Affairs; Minister responsible for the (Pangnirtung) Minister of Culture and Heritage; Utility Rates Review Council Hon. -

Tuesday, February 16, 1999

CANADA 1st SESSION 36th PARLIAMENT VOLUME 137 NUMBER 111 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, February 16, 1999 THE HONOURABLE GILDAS L. MOLGAT SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue.) Debates: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 995-5805 Published by the Senate Available from Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa K1A 0S9, Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 2591 THE SENATE Tuesday, February 16, 1999 The Senate met at 2:00 p.m., the Speaker in the Chair. are given “lai see” by those who are married. Those little red envelopes have money inside for good fortune. Prayers. Many traditional Chinese New Year foods are chosen because VISITORS IN THE GALLERY their names are phonetically close to good luck phrases. Eating these foods bestows their wishes on those who consume them. The Hon. the Speaker: Honourable senators, I should like to Dried oysters sound like “good business”; lotus seeds like “many draw your attention to the presence in the gallery of a delegation sons”; while whole fish with heads and tails are cooked, of parliamentarians from the Republic of Estonia. It is led by symbolizing abundance. Mr. Toomas Savi, President of the Riigikogu of the Republic of (1410) Estonia. Mr. Savi is accompanied by His Excellency Kalev Grigore Stoicesku, Ambassador of the Republic of Estonia Traditionally, Chinese decorate their homes and businesses to Canada. with potted flowers as an important symbol of new growth and prosperity. As in Western homes with Christmas trees, trees of On behalf of all honourable senators, I welcome you to the peach or cherry blossoms are cut and sold in New Year markets Senate of Canada. -

Mining, Mineral Exploration and Geoscience Contents

Overview 2020 Nunavut Mining, Mineral Exploration and Geoscience Contents 3 Land Tenure in Nunavut 30 Base Metals 6 Government of Canada 31 Diamonds 10 Government of Nunavut 3 2 Gold 16 Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated 4 4 Iron 2 0 Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office 4 6 Inactive projects 2 4 Kitikmeot Region 4 9 Glossary 2 6 Kivalliq Region 50 Guide to Abbreviations 2 8 Qikiqtani Region 51 Index About Nunavut: Mining, Mineral Exploration and by the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA), the regulatory Geoscience Overview 2020 body which oversees stock market and investment practices, and is intended to ensure that misleading, erroneous, or This publication is a combined effort of four partners: fraudulent information relating to mineral properties is not Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada published and promoted to investors on the stock exchanges (CIRNAC), Government of Nunavut (GN), Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI), and Canada‑Nunavut Geoscience Office overseen by the CSA. Resource estimates reported by mineral (CNGO). The intent is to capture information on exploration and exploration companies that are listed on Canadian stock mining activities in 2020 and to make this information available exchanges must be NI 43‑101 compliant. to the public and industry stakeholders. We thank the many contributors who submitted data and Acknowledgements photos for this edition. Prospectors and mining companies are This publication was written by the Mineral Resources Division welcome to submit information on their programs and photos at CIRNAC’s Nunavut Regional Office (Matthew Senkow, for inclusion in next year’s publication. Feedback and comments Alia Bigio, Samuel de Beer, Yann Bureau, Cedric Mayer, and are always appreciated. -

Our Baffinland: Digital Indigenous Democracy

ECONOMY Our Baffinland: Digital Indigenous Democracy Norman Cohn & Zacharias Kunuk s an upsurge of development due to global gency for Baffin Island Inuit facing one of the largest warming threatens to overwhelm communities mining developments in Canadian history. Baffinland iAn the resource-rich Canadian Arctic, how can Inuit Iron Mines Corporation’s (BIM) Mary River project in those communities be more fully involved and consulted is a $6 billion open-pit extraction of extremely high- in their own language? What tools are needed to grade iron ore that, if fully exploited, could continue make knowledgeable decisions? Communicating in for 100 years. The mining site, in the centre of North writing with oral cultures makes ‘consulting’ one- Baffin Island about half-way between the Inuit com- sided: giving people thousands of pages they can’t munities of Pond Inlet and Igloolik, requires a 150 read is unlikely to produce an informed, meaningful km railroad built across frozen tundra to transport response. Now for the first time Internet audiovisual ore to a deep-water port where the world’s largest su- tools enable community-based decision-making in pertankers will carry it to European and Asian mar- oral Inuktitut that meets higher standards of consti- kets. Operating the past several years under a tutional and international law, and offers a new temporary exploratory permit, BIM filed its Final En- model for development in Indigenous homelands. To vironmental Impact Statement (FEIS) with the Nunavut meet these standards, Inuit must get -

Appendix D: Workshop Notes

APPENDIX D: WORKSHOP NOTES 151 Results of Community Workshops Conducted for Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation’s Phase 2 Proposal Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation Mary River Project, Phase 2 Workshop #1: Contemporary Inuit Land Use in the Eclipse Sound and Navy Board Inlet Areas -Invited Persons Workshop Notes- Participants: Joshua Arreak (Hamlet of Pond Inlet nominee) Jennifer St Paul Butler (Baffinland) Ludy Pudluk (Hamlet of Pond Inlet nominee) Jason Prno (Jason Prno Consulting Services Ltd.) Jimmy Pitseolak (Pond Inlet HTO nominee) Jason Lewis (Avati) Elijah Panikpakoochoo (Pond Inlet HTO nominee) Justin Buller (QIA) Joanasie Mucpa (Pond Inlet HTO nominee) Jeff Higdon (Consultant to QIA) Michael Inuarak (Nasivvik High School nominee) Kunnuk Qamaniq (Nasivvik High School nominee) Timothy Aksarjuk (QIA nominee) Paniloo Sangoya (QIA nominee) Dates: March 3-4, 2015 Other Information: At the beginning of the workshop, Baffinland spent time presenting details of the Phase 2 proposal and describing the purpose and objectives of the workshop. Much of the remaining time was then spent discussing and documenting contemporary seasonal land use activities in the Eclipse Sound and Navy Board Inlet areas. The workshop was facilitated by Jason Prno. Workshop notes were recorded by Jennifer St Paul Butler and Jason Lewis, and were compiled by Jason Lewis. The workshop was observed by Justin Buller and Jeff Hidgon of the QIA. Information provided in the workshop (included below) is attributed to individual participants or to group discussion where appropriate. Where an attribution is not listed, the information provider(s) were unrecorded. Notes: Workshop participants indicated that the Inuit calendar in this part of the Arctic (the Pond Inlet – Eclipse Sound area) is divided into five seasons, not six as presented in the North Baffin Land Use Plan.