Maintenance Report Cov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Laurel Highlands Pennsylvania

The LaureL highLands pennsylvania 2010 Travel Guide a place of WONDER You really should be here! Make New Family Memories Seven Springs Mountain Resort is the perfect place to reconnect and make a new memory with your family and friends! Whether the snow is blanketing the ground, the leaves are gilded in rich autumn hues or the sun is shining and there is a warm summer breeze, Seven Springs is your escape destination. At Pennsylvania’s largest resort, you can unwind at Trillium Spa, take a shot at sporting clays, explore 285 acres of skiable terrain, enjoy the adrenaline rush of a snowmobile tour – the opportunities are endless! At Seven Springs, we strive to provide you and yours with legendary customer service, value and warm lifelong memories. What are you waiting for? You really should be here! Seasonal packages available year-round - call 800.452.2223 or visit us on line at www.7Springs.com. Seven Springs Mountain Resort 777 Waterwheel Drive | Seven Springs, PA 15622 800.452.2223 | www.7Springs.com s you look through the 2010 Laurel AHighlands Travel Guide, you may notice the question, have you ever wondered, used a lot! Have you ever wondered what it would be like to 1won-der: \wən-dər\ n 1 a: a cause of astonishment or admiration: marvel b: miracle 2 : the quality of exciting amazed admiration 3 a : rapt attention or astonishment at something awesomely mysterious or new to one’s experience 2won-der: v won·dered; won·der·ing 1 a : to be in a state of wonder b : to feel surprise 2 : to feelhave curiosity oryou doubt 3 won-derever: adj WONDERED? wondrous, wonderful: as a : exciting amazement or admiration b : effective or efficient far beyond anything previously known or anticipated. -

Warner Spur Multi-Use Trail Master Plan

Warner Spur Multi-Use Trail Master Plan Chester County Tredyffrin Township Prepared by: December 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Prepared for the In partnership with Tredyffrin Township Chester County Board of Commissioners Plan Advisory Committee Michelle Kichline Zachary Barner, East Whiteland Township Kathi Cozzone Mahew Baumann, Tredyffrin Township Terence Farrell Les Bear, Indian Run Road Association Stephen Burgo, Tredyffrin Township Carol Clarke, Great Valley Association Consultants Rev. Abigail Crozier Nestlehu, St. Peter's Church McMahon Associates, Inc. Jim Garrison, Vanguard In association with Jeff Goggins, Trammel Crow Advanced GeoServices, Corp. Rachael Griffith, Chester County Planning Commission Glackin Thomas Panzak, Inc. Amanda Lafty, Tredyffrin Township Transportation Management Association of Tim Lander, Open Land Conservancy of Chester County Chester County (TMACC) William Martin, Tredyffrin Township Katherine McGovern, Indian Run Road Association Funding Aravind Pouru, Atwater HOA Dave Stauffer, Chester County Department of Facilities and Parks Grant funding provided from the William Penn Brian Styche, Chester County Planning Commission Foundation through the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission’s Regional Trails Program. Warner Spur Multi-Use Trail Master Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 | Background 3 | Conceptual Improvement Plan Introduction 1-1 Conceptual Improvement Plan 3-1 History and Previous Plans 1-1 Conceptual Design Exhibits for Key 3-8 Connections and Crossings Study Area 1-2 Public and Emergency -

Welcome, New Board Members Got to Know the Late Director of the “Certainly the Rainforest Is Important, but So Is the Temperate Forest,” Asserts Schmidt

Thomas M. Schmidt While with the WPC, Schmidt directed several key proj- ects, including the Pittsburgh Park and Playground Fund, VP & General Counsel, retired which constructed parklets, playgrounds and greenways Western Pennsylvania Conservancy to bring natural amenities to disadvantaged neighborhoods; the Ligonier Easement Project, one of the largest conser- I have been a director of the vation and scenic easement programs in Pennsylvania, Allegheny Land Trust since it was protecting over 4,000 acres; and the Fallingwater Museum, created at the recommendation for which he raised funds, worked with curators and of Allegheny County 2001. contractors, and added features that helped increase “Like many people in our region, I annual visitation. A publication of Allegheny Land Trust Summer 2002 have been interested in the outdoors In addition, Schmidt is a founder of the Land Trust and science since I was young. My Alliance and trustee of the National Aviary. mother was a bird watcher, and I Welcome, New Board Members got to know the late director of the “Certainly the rainforest is important, but so is the temperate forest,” asserts Schmidt. “The most recent Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Dr. M. Graham Robert T. MacLachlan, MD helped secure preservation of Netting, who became a sort of mentor. As a teenager, Bioblitz inventories of our largest urban parks found A physician by training, MacLachlan has no formal Wingfield Pines, the Trust’s newest I participated in one of the museum’s paleontology unknown and unexpected species—further proof that we environmental experience, but since a young age, he’s acquisition. expeditions out West. -

INVESTING in OUR FUTURE Quantifying the Impact of Completing the East Coast Greenway in the Delaware River Watershed

INVESTING IN OUR FUTURE Quantifying the Impact of Completing the East Coast Greenway in the Delaware River Watershed Report Prepared For: Prepared By: Executive Summary Completing the East Coast Greenway in the Delaware Watershed will provide: 175 2 MILES OF MULTI-USE TRAIL 2,460 TEMPORARY JOBS $840M IN ANNUAL TOURISM BENEFITS ($4.8M/MILE LOCAL ECONOMIC IMPACT) $2.2B ONE-TIME ECONOMIC BENEFITS Table of Contents What is the East Coast Greenway? 5 The East Coast Greenway in the Delaware Watershed 6 What the Greenway Connects 8 Transport + Safety Benefits 10 Case Study: Jack A. Markell Trail 12 Economic Benefits + Planning for Equity 14 Case Study: Bristol Borough 20 Health Benefits 22 Environmental Benefits 24 Case Study: Riverfront North Partnership 26 Conclusion 28 Bartram’s Mile segment of East Coast Greenway along west bank of Schuylkill River in Philadelphia. East Coast Greenway Alliance photo Sources 30 On the cover: celebrations on Schuylkill River Trail Schuylkill Banks photos ME Calais Bangor Augusta Portland NH Delaware Portsmouth MA Boston Watershed NY Hartford New Haven CT Providence NJ RI PA New York Philadelphia Trenton Wilmington MD Baltimore Washington DC Annapolis DE Fredericksburg VA Richmond 4 Norfolk NC Raleigh Fayetteville New Bern Wilmington SC Myrtle Beach Charleston GA Savannah Brunswick Jacksonville St.Augustine FL Melbourne Miami Key West greenway.org What is the East Coast Greenway? The East Coast Greenway is developing into one of the nation’s longest continuous biking and walking paths, connecting 15 states and 450 communities from Key West, Florida, to Calais, Maine. The in-progress Greenway is a place that bicyclists, walkers, runners, skaters, horseback riders, wheelchair users, and cross-country skiers of all ages and abilities can enjoy. -

Cedar Grove Environmental Resource Inventory

ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY TOWNSHIP OF CEDAR GROVE ESSEX COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Prepared by: Cedar Grove Environmental Commission 525 Pompton Avenue Cedar Grove, NJ 07009 December 2002 Revised and updated February 2017 i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………......... 1 2.0 PURPOSE………………………………………………………………….. 2 3.0 BACKGROUND…………………………………………………………… 4 4.0 BRIEF HISTORY OF CEDAR GROVE…………………………………. 5 4.1 The Canfield-Morgan House…………………………………………….. 8 5.0 PHYSICAL FEATURES………………………………………………….. 10 5.1 Topography………………………………………………………………... 10 5.2 Geology……………………………………………………………………. 10 5.3 Soils………………………………………………………………………… 13 5.4 Wetlands…………………………………………………………………... 14 6.0 WATER RESOURCES…………………………………………………… 15 6.1 Ground Water……………………………………………………………... 15 6.1.1 Well-Head Protection Areas…………………………………………. 15 6.2 Surface Water…………………………………………………………….. 16 6.3 Drinking Water…………………………………………………………….. 17 7.0 CLIMATE…………………………………………………………………… 20 8.0 N ATURAL HAZARDS…………………………………………………… 22 8.1 Flooding……………………………………………………………………. 22 8.2 Radon………………………………………………………………………. 22 8.3 Landslides…………………………………………………………………. 23 8.4 Earthquakes………………………………………………………………. 24 9.0 WILDLIFE AND VEGETATION…………………………………………. 25 9.1 Mammals, Reptiles, Amphibians, and Fish……………………………. 26 9.2 Birds………………………………………………………………………… 27 9.3 Vegetation………………………………………………………………….. 28 10.0 ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY………………………………………...... 29 10.1 Non-Point Source Pollution……………………………………………... 29 10.1.1 Integrated Pest Management (IPM)……………………………… 32 10.2 Known Contaminated Sites……………………………………………. -

Safety and Etiquette Guide

SAFETY GUIDELINES A Trail for Everyone, About the Montour Trail No Matter Their Abilities! Honored by the Pennsylvania Department of Natural Resources People with physical disabilities are welcome to use Trail Rules for ALL USERS as the state’s 2017 Trail of the the Montour Trail, and the Council’s mobility-impaired Year, the Montour Trail is the policies address their special needs. All trail users are expected to obey the following rules, longest suburban rail-trail in the which are posted at all major trailheads: • Wheelchairs are always permitted, whether U.S., encompassing 63 miles. 1. No motorized vehicles powered or not. Running through communities west and south of • Other powered mobility devices are allowed if they 2. Keep right, except to pass Pittsburgh, the trail follows the abandoned rights of way are less than 36 inches wide and travel less than 3. Warn before passing of the Montour Railroad and the Peters Creek branch of 15 mph under their own power on a level surface. 4. Stay on the trail the Pennsylvania Railroad. • E-bikes, which are pedal devices with an electric 5. Leash your pet assist motor, must meet certain conditions: power The Montour Trail connects Pittsburgh International 6. Trail open daily, dawn to dusk rating less than 750 watts, weight under 100 Airport to the Great Allegheny Passage (GAP), which pounds, and top speed 15 mph. joins up with the C&O Canal Towpath that leads to 7. Camp only in designated areas Washington, DC. • Devices powered by internal combustion engines 8. No horses are never permitted on the Montour Trail. -

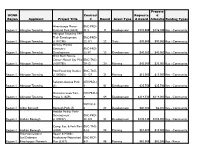

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste D Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type D Award Allocatio Funding Types

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Alverthorpe Manor BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Cultural Park (6422) 11-3 11 Development $223,000 $136,900 Key - Community Abington Township TAP Trail- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township (1101296) 22-171 22 Trails $90,000 $90,000 Key - Community Ardsley Wildlife Sanctuary- BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Development 22-37 22 Development $40,000 $40,000 Key - Community Briar Bush Nature Center Master Site Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1007785) 20-12 20 Planning $42,000 $37,000 Key - Community Pool Feasibility Studies BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1100063) 21-127 21 Planning $15,000 $15,000 Key - Community Rubicam Avenue Park KEY-PRD-1- Region 1 Abington Township (1) 1 01 Development $25,750 $25,700 Key - Community Demonstration Trail - KEY-PRD-4- Region 1 Abington Township Phase I (1659) 4 04 Development $114,330 $114,000 Key - Community KEY-SC-3- Region 1 Aldan Borough Borough Park (5) 6 03 Development $20,000 $2,000 Key - Community Ambler Pocket Park- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Ambler Borough (1102237) 23-176 23 Development $102,340 $102,000 Key - Community Comp. Rec. & Park Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Ambler Borough (4438) 8-16 08 Planning $10,400 $10,000 Key - Community American Littoral Upper & Middle Soc/Delaware Neshaminy Watershed BRC-RCP- Region 1 Riverkeeper Network Plan (3337) 6-9 06 Planning $62,500 $62,500 Key - Rivers Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Valley View Park - Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Aston Township (1100582) 21-114 21 Development $184,000 $164,000 Key - Community Comp. -

Appendix IV: Regional Vision Project Lists for Southwestern Pennsylvania

Appendix IV: Regional Vision Project Lists for Southwestern Pennsylvania IV-2: Projects Currently Beyond Fiscal Capacity Appendix IV-2: Projects Currently Beyond Fiscal Capacity The following projects are consistent with the Regional Vision of a world-class, safe and well maintained transportation system that provides mobility for all, enables resilient communities, and supports a globally competitive economy. While beyond current fiscal capacity, these projects would contribute to achievement of the Regional Vision. They are listed herein to illustrate additional priority projects in need of funding. Project Type Project Allegheny Port Authority of Allegheny West Busway BRT Extension – Downtown to County Pittsburgh International Airport Extend East Busway to Monroeville (including Braddock, East Pittsburgh, Turtle Creek) Improved Regional Transit Connection Facilities Enhanced Rapid Transit Connection – Downtown to North Hills Technological Improvements New Maintenance Garage for Alternative Fuel Buses Purchase of 55 New LRT Vehicles Park and Ride – Additional Capacity Pittsburgh International Airport Enlow Airport Access Road Related New McClaren Road Bridge High Quality Transit Service and Connections Clinton Connector US 30 and Clinton Road: Intersection Improvements Roadway / Bridge SR 28: Reconstruction PA 51: Flooding – Liberty Tunnel to 51/88 Intersection SR 22 at SR 48: Reconstruction and Drainage SR 837: Reconstruction SR 22/30: Preservation to Southern Beltway SR 88: Reconstruction – Conner Road to South Park SR 351: Reconstruction SR 3003 (Washington Pike): Capacity Upgrades SR 3006: Widening – Boyce Road to Route 19 Project Type Project Waterfront Access Bridge: Reconstruction Elizabeth Bridge: Preservation Glenfield Bridge: Preservation I-376: Bridge Preservation over Rodi Road Kennywood Bridge: Deck Replacement – SR 837 over Union RR Hulton Road Bridge: Preservation 31st Street Bridge: Preservation Liberty Bridge: Preservation Marshall Avenue Interchange: Reconstruction 7th and 9th St. -

The Schuylkill River Trail from the Past to the Present

M O N T G O M E R Y C O U N T Y P A T R A I L S Y S T E M The Schuylkill River Trail From the past to the present. From the historic river Extension. For those seeking public transportation to the trail, towns of Conshohocken, Norristown, and Pottstown to the SEPTA offers excellent access via regional rail service and bus rolling hills of Valley Forge National Historical Park. The lines in Miquon, Spring Mill, Conshohocken, and Norristown. Schuylkill River Trail in Montgomery County takes visitors Visit www.montcopa.org/schuylkillrivertrail for more through a rich blend of natural, cultural, and historical information or contact Montgomery County Division of Parks, resources. The trail runs through a variety of urban, Trails, & Historic Sites at 610.278.3555. suburban, and rural landscapes, offering nearly 20 miles to hikers, joggers, bicyclists, equestrians, and in-line skaters. Trail Rules The Schuylkill River Trail (SRT) is the spine of the • Trail speed limit is 15 mph Schuylkill River National and State Heritage Corridor. When completed, the trail will run over 100 miles from the coal region • Trail is open dawn to dusk of Schuylkill County to the Delaware River in Philadelphia. • No unauthorized motor vehicles are permitted on trail Evidence of several centuries of industrial use remains • Dogs must be leashed where river and canal navigation, quarrying of limestone and • Owners are responsible for cleaning up all pet waste iron ore, and production of iron and steel have succeeded each • No littering—please practice “Carry In - Carry Out” other as mainstays of this region’s economy. -

Hiking Trails

0a3 trail 0d4 trail 0d5 trail 0rdtr1 trail 14 mile connector trail 1906 trail 1a1 trail 1a2 trail 1a3 trail 1b1 trail 1c1 trail 1c2 trail 1c4 trail 1c5 trail 1f1 trail 1f2 trail 1g2 trail 1g3 trail 1g4 trail 1g5 trail 1r1 trail 1r2 trail 1r3 trail 1y1 trail 1y2 trail 1y4 trail 1y5 trail 1y7 trail 1y8 trail 1y9 trail 20 odd peak trail 201 alternate trail 25 mile creek trail 2b1 trail 2c1 trail 2c3 trail 2h1 trail 2h2 trail 2h4 trail 2h5 trail 2h6 trail 2h7 trail 2h8 trail 2h9 trail 2s1 trail 2s2 trail 2s3 trail 2s4 trail 2s6 trail 3c2 trail 3c3 trail 3c4 trail 3f1 trail 3f2 trail 3l1 trail 3l2 trail 3l3 trail 3l4 trail 3l6 trail 3l7 trail 3l9 trail 3m1 trail 3m2 trail 3m4 trail 3m5 trail 3m6 trail 3m7 trail 3p1 trail 3p2 trail 3p3 trail 3p4 trail 3p5 trail 3t1 trail 3t2 trail 3t3 trail 3u1 trail 3u2 trail 3u3 trail 3u4 trail 46 creek trail 4b4 trail 4c1 trail 4d1 trail 4d2 trail 4d3 trail 4e1 trail 4e2 trail 4e3 trail 4e4 trail 4f1 trail 4g2 trail 4g3 trail 4g4 trail 4g5 trail 4g6 trail 4m2 trail 4p1 trail 4r1 trail 4w1 trail 4w2 trail 4w3 trail 5b1 trail 5b2 trail 5e1 trail 5e3 trail 5e4 trail 5e6 trail 5e7 trail 5e8 trail 5e9 trail 5l2 trail 6a2 trail 6a3 trail 6a4 trail 6b1 trail 6b2 trail 6b4 trail 6c1 trail 6c2 trail 6c3 trail 6d1 trail 6d3 trail 6d5 trail 6d6 trail 6d7 trail 6d8 trail 6m3 trail 6m4 trail 6m7 trail 6y2 trail 6y4 trail 6y5 trail 6y6 trail 7g1 trail 7g2 trail 8b1 trail 8b2 trail 8b3 trail 8b4 trail 8b5 trail 8c1 trail 8c2 trail 8c4 trail 8c5 trail 8c6 trail 8c9 trail 8d2 trail 8g1 trail 8h1 trail 8h2 trail 8h3 trail -

Entire Bulletin

Volume 40 Number 44 Saturday, October 30, 2010 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 6247—6376 Agencies in this issue The General Assembly The Courts Capitol Preservation Committee Department of Aging Department of Environmental Protection Department of General Services Department of Health Department of Labor and Industry Department of Revenue Department of State Department of Transportation Fish and Boat Commission Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Philadelphia Regional Port Authority State Board of Physical Therapy State Conservation Commission Detailed list of contents appears inside. Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporters (Master Transmittal Sheets): No. 431, October 2010 published weekly by Fry Communications, Inc. for the PENNSYLVANIA Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- BULLETIN reau, 641 Main Capitol Building, Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, (ISSN 0162-2137) under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publi- cation and effectiveness of Commonwealth Documents). Subscription rate $82.00 per year, postpaid to points in the United States. Individual copies $2.50. Checks for subscrip- tions and individual copies should be made payable to ‘‘Fry Communications, Inc.’’ Periodicals postage paid at Harris- burg, Pennsylvania. Postmaster send address changes to: Orders for subscriptions and other circulation matters FRY COMMUNICATIONS should be sent to: Attn: Pennsylvania Bulletin 800 W. Church Rd. Fry Communications, Inc. Attn: Pennsylvania Bulletin Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania 17055-3198 800 W. Church Rd. (717) 766-0211 ext. 2340 Mechanicsburg, PA 17055-3198 (800) 334-1429 ext. 2340 (toll free, out-of-State) (800) 524-3232 ext. 2340 (toll free, in State) Copyright 2010 Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Editorial preparation, composition, printing and distribution of the Pennsylvania Bulletin is effected on behalf of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania by FRY COMMUNICATIONS, Inc., 800 W. -

800.237.8590 • Visitjohnstownpa.Com • 1

800.237.8590 • visitjohnstownpa.com • 1 PUBLISHED BY Greater Johnstown/Cambria County Convention & Visitors Bureau 111 Roosevelt Blvd., Ste. A Introducing Johnstown ..................right Johnstown, PA 15906-2736 ...............7 814-536-7993 Map of the Cambria County 800-237-8590 The Great Flood of 1889 .....................8 www.visitjohnstownpa.com Industry & Innovation ........................12 16 VISITOR INFORMATION Cambria City ....................................... Introducing Johnstown By Dave Hurst 111 Roosevelt Blvd., Our Towns: Loretto, Johnstown, PA 15906 Ebensburg & Cresson ........................18 If all you know about Johnstown is its flood, you are Mon.-Fri. 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Outdoor Recreation ...........................22 missing out on much of its history – and a lot of fun! Located on Rt. 56, ½ In addition to being the “Flood City,” Johnstown has Bikers Welcome! .................................28 mile west of downtown been a canal port, a railroad center, a steelmaking ATV: Rock Run .....................................31 Johnstown beside Aurandt center, and the new home for a colorful assortment Paddling & Boating ............................32 Auto Sales of European immigrants. Cycling .................................................36 INCLINED PLANE In 2015, Johnstown was proudly named the first .....................................38 VISITOR CENTER Arts & Culture “Kraft Hockeyville USA,” recognizing the community as 711 Edgehill Dr., Family Fun & Entertainment .............40 the most passionate hockey town