Environmental History of the Blacklick Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CTT Economic Impact Study

THE POTENTIAL ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF THE PROPOSED CAROLINA THREAD TRAIL FINAL REPORT MARCH 2007 Submitted to: Catawba Lands Conservancy 105 West Morehead Street, Suite B Charlotte, NC 28202 Submitted by: Econsult Corporation th 6 Floor 3600 Market Street Philadelphia, PA 19104 and Greenways Incorporated 5850 Fayetteville Road, Suite 211 Durham, NC 27713 MarchTABLE 2007 OF CONTENTS A REGIONAL ECONOMIC IMPACT STUDY OF THE CAROLINA THREAD TRAIL Executive Summary i 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 Potential Economic Benefits of the Carolina Thread Trail 4 2.1 Enhanced Property Values and Local Property Tax Revenues 5 2.2 Increased Tourism 7 2.3 Construction Investment Impacts 8 2.4 Business Expansion / Economic Development 10 2.5 Air and Water Quality 15 2.6 Increased Aggregate Recreation Value 21 2.7 Return on Investment 26 3.0 Summary and Conclusion 30 Appendix A. Enhanced Property Values 34 B. Economic And Fiscal Impact Model Methodology 46 C. Improved Water and Air Quality 49 March 2007 A REGIONAL ECONOMIC IMPACT STUDY OF THE CAROLINA THREAD TRAIL i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The proposed Carolina Thread Trail (“the Trail”) will span approximately 500 miles across a 15- county region, including parts of both North and South Carolina. In addition to providing open space and enhanced recreational opportunities to residents and visitors, the Trail will be designed to “thread” communities together along routes designed by the communities themselves. The Trail is expected to help the region continue to compete aggressively with other rapidly growing and quickly developing metro areas of the country by providing local amenities for area residents, visitors, and businesses. -

West Virginia Blue Book 2015 - 2016

WEST VIRGINIA BLUE BOOK 2015 - 2016 Clark S. Barnes, Senate Clerk Charleston, West Virginia II WEST VIRGINIA BLUE BOOK CONTENTS Pages 1-336 Section 1 - Executive State Elective and Appointive Officers; Departmental Registers; Salaries and Terms of Office; Boards and Commissions 337-512 Section 2 - Legislative Rosters of Senate and House of Delegates; Maps, Senatorial and Delegate Districts; Legislative Agencies and Organizations; Historical Information 513-542 Section 3 - Judicial Justices of the State Supreme Court of Appeals; Clerks and Officers; Maps and Registers; Circuit Courts and Family Court Judges; Magistrates 543-628 Section 4 - Constitutional Constitution of the United States; Constitution of West Virginia 629-676 Section 5 - Institutions Correctional Institutions; State Health Facilities; State Schools and Colleges; Denominational and Private Colleges 677-752 Section 6 - Federal President and Cabinet; State Delegation in Congress; Map, Congressional Districts; Governors of States; Federal Courts; Federal Agencies in West Virginia 753-766 Section 7 - Press, Television & Radio, Postal 767-876 Section 8 - Political State Committees; County Chairs; Organizations; Election Returns 877-946 Section 9 - Counties County Register; Historical Information; Statistical Facts and Figures 947-1042 Section 10 - Municpalities Municipal Register; Historical Information; Statistical Facts and Figures 1043-1116 Section 11 - Departmental, Statistical & General Information 1117-1133 Section 12 - Index FOREWORD West Virginia Blue Book 2015 - 2016 The November 2014 election delivered a political surprise. In January the following year, for the first time in over 80 years, the Republicans controlled both Chambers of the State Legislature. New names, new faces dominated the political landscape. William P. Cole, III, a Senator for only two years, bypassed the usual leadership hierarchy and assumed the position of Senate President and Lieutenant Governor. -

The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1989 The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal Stuart William Wells University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Wells, Stuart William, "The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal" (1989). Theses (Historic Preservation). 350. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/350 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Wells, Stuart William (1989). The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/350 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Wells, Stuart William (1989). The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/350 UNIVERSITY^ PENNSYLVANIA. LIBRARIES THE SCHUYLKILL NAVIGATION AND THE GIRARD CANAL Stuart William -

Upper Mon River Trail

Upper Monongahela River Water Trail Map and Guide Water trails are recreational waterways on a lake, river, or ocean between specific locations, containing access points and day-use and/or camping sites for the boating public. Water trails emphasize low-impact use and promote stewardship of the resources. Explore this unique West Virginia and Pennsylvania water trail. For your safety and enjoyment: Always wear a life jacket. Obtain proper instruction in boating skills. Know fishing and boating regulations. Be prepared for river hazards. Carry proper equipment. THE MONONGAHELA RIVER The Monongahela River, locally know as “the Mon,” forms at the confluence of the Tygart and West Fork Rivers in Fairmont West Virginia. It flows north 129 miles to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where it joins the Allegheny River to form the Ohio River. The upper section, which is described in this brochure, extends 68 miles from Fairmont to Maxwell Lock and Dam in Pennsylvania. The Monongahela River formed some 20 million years ago. When pioneers first saw the Mon, there were many places where they could walk across it. The Native American named the river “Monongahela,” which is said to mean “river with crumbling or falling banks.” The Mon is a hard-working river. It moves a large amount of water, sediment, and freight. The average flow at Point Marion is 4,300 cubic feet per second. The elevation on the Upper Mon ranges from 891 feet in Fairmont to 763 feet in the Maxwell Pool. PLANNING A TRIP Trips on the Mon may be solitary and silent, or they may provide encounters with motor boats and water skiers or towboats moving barges of coal or limestone. -

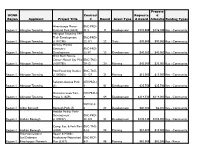

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste D Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type D Award Allocatio Funding Types

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Alverthorpe Manor BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Cultural Park (6422) 11-3 11 Development $223,000 $136,900 Key - Community Abington Township TAP Trail- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township (1101296) 22-171 22 Trails $90,000 $90,000 Key - Community Ardsley Wildlife Sanctuary- BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Development 22-37 22 Development $40,000 $40,000 Key - Community Briar Bush Nature Center Master Site Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1007785) 20-12 20 Planning $42,000 $37,000 Key - Community Pool Feasibility Studies BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1100063) 21-127 21 Planning $15,000 $15,000 Key - Community Rubicam Avenue Park KEY-PRD-1- Region 1 Abington Township (1) 1 01 Development $25,750 $25,700 Key - Community Demonstration Trail - KEY-PRD-4- Region 1 Abington Township Phase I (1659) 4 04 Development $114,330 $114,000 Key - Community KEY-SC-3- Region 1 Aldan Borough Borough Park (5) 6 03 Development $20,000 $2,000 Key - Community Ambler Pocket Park- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Ambler Borough (1102237) 23-176 23 Development $102,340 $102,000 Key - Community Comp. Rec. & Park Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Ambler Borough (4438) 8-16 08 Planning $10,400 $10,000 Key - Community American Littoral Upper & Middle Soc/Delaware Neshaminy Watershed BRC-RCP- Region 1 Riverkeeper Network Plan (3337) 6-9 06 Planning $62,500 $62,500 Key - Rivers Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Valley View Park - Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Aston Township (1100582) 21-114 21 Development $184,000 $164,000 Key - Community Comp. -

1 Steel Industry Heritage Corporation Ethnographic Survey of The

1 Steel Industry Heritage Corporation Ethnographic Survey of the following communities in the Allegheny-Kiskiminetas River Valley: New Kensington Arnold Braeburn Tarentum Brackenridge Natrona West Natrona ("Ducktown") Natrona Heights With Brief Forays into: Vandergrift Buffalo Township Chris J. Magoc Brackenridge, Pennsylvania October 25, 1993 FINAL SUMMARY REPORT 2 CONTENTS Introduction: Conception and Evolution of Fieldwork 3 Overview: Physical, Historical and Cultural Geography 5 Shifting/Current Settlement Patterns 18 Social-Cultural life 21 New Kensington-Arnold Case studies: Polish- and Italian-American heritage Tarentum Case study: Corpus Christi Sawdust Carpet Display at Sacred Heart-St. Peter's Church Brackenridge Case Study: Reunion of "The Street" people Case Study: Industrial lore at Allegheny Ludlum Natrona/Natrona Heights/West Natrona ("Ducktown") Vandergrift Braeburn Additional thematic connections among communities Cultural heritage issues of concern 53 Ethnicity/Religion Occupation Family/Community Environmental Recommendations for interpretive public programming 63 and follow-up studies needed Social and cultural inventory: List of contacts Bibliographical Essay on written, oral, visual 68 resources in the region 3 I. Introduction: Conception and Evolution of Fieldwork The conception and execution of this ethnographic study derives from the premise that an eight-community region lying along the border of Allegheny and Westmoreland counties, near the confluence of the Allegheny and Kiskiminetas Rivers, has figured prominently in the development of the rich cultural and industrial heritage of southwestern Pennsylvania--i.e., within the designated broader "Study Area" of the Steel Industrial Heritage Corporation (SIHC). A native (though not a life-long resident) of the region, I began with some rudimentary knowledge of the industrial and cultural resources of the projected study area. -

Free to Speculate

ECONOMICHISTORY Free to Speculate BY KARL RHODES s Britain’s secretary of state land grants, so he reasoned that a much British frontier for the Colonies, Wills Hill, bigger proposal would have a much policy threatened Athe Earl of Hillsborough, vehe- smaller chance of winning approval. mently opposed American settlement But Franklin and his partners turned Colonial land west of the Appalachian Mountains. As Hillsborough’s tactic against him. They the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly’s increased their request to 20 million speculation agent in London, Benjamin Franklin acres only after expanding their partner- on the eve of enthusiastically advocated trans-Appa- ship to include well-connected British lachian expansion. The two bitter ene- bankers and aristocrats, many of them the American mies disagreed about many things, and Hillsborough’s enemies. This Anglo- British land policy in the Colonies was American alliance proposed a new colo- Revolution at or near the top of the list. ny called Vandalia, a name that Franklin In the late 1760s, Franklin joined recommended to honor the queen’s pur- forces with Colonial land speculators ported Vandal ancestry. The new colony who were asking King George’s Privy would have included nearly all of what Council to validate their claim on more is now West Virginia, most of eastern than 2 million acres along the Ohio Kentucky, and a portion of southwest River. It was a large western land grab — Virginia, according to a map in Voyagers even by Colonial American standards to the West by Harvard historian Bernard — and the speculators fully expected Bailyn. Hillsborough to object. -

800.237.8590 • Visitjohnstownpa.Com • 1

800.237.8590 • visitjohnstownpa.com • 1 PUBLISHED BY Greater Johnstown/Cambria County Convention & Visitors Bureau 111 Roosevelt Blvd., Ste. A Introducing Johnstown ..................right Johnstown, PA 15906-2736 ...............7 814-536-7993 Map of the Cambria County 800-237-8590 The Great Flood of 1889 .....................8 www.visitjohnstownpa.com Industry & Innovation ........................12 16 VISITOR INFORMATION Cambria City ....................................... Introducing Johnstown By Dave Hurst 111 Roosevelt Blvd., Our Towns: Loretto, Johnstown, PA 15906 Ebensburg & Cresson ........................18 If all you know about Johnstown is its flood, you are Mon.-Fri. 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Outdoor Recreation ...........................22 missing out on much of its history – and a lot of fun! Located on Rt. 56, ½ In addition to being the “Flood City,” Johnstown has Bikers Welcome! .................................28 mile west of downtown been a canal port, a railroad center, a steelmaking ATV: Rock Run .....................................31 Johnstown beside Aurandt center, and the new home for a colorful assortment Paddling & Boating ............................32 Auto Sales of European immigrants. Cycling .................................................36 INCLINED PLANE In 2015, Johnstown was proudly named the first .....................................38 VISITOR CENTER Arts & Culture “Kraft Hockeyville USA,” recognizing the community as 711 Edgehill Dr., Family Fun & Entertainment .............40 the most passionate hockey town -

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service

NPS Form 10*00* OMB Approval No. 101+0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Owned Highway Bridges Section number 7 Page 1 Bridges included in Pennsylvania Historic Highway Bridges Thematic Group Stone Arch Bridges S-l Pondtown Mill Bridge Unknown L.R. 01009, Adams County S-2 Bridge in Jefferson Borough 1901 L.R. 02085, Allegheny County S-3 Bridge in Shaler Township 1915 L.R. 02349, Allegheny County S-4 "S" Bridge 1919 L.R. 06024, Berks County S-5 Bridge in Albany Township 1841 L.R. 06172, Berks County S-6 Bridge in Yardley Borough 1889 L.R. 09023, Bucks County S-7 Newtown Creek Bridge 1796 L.R. 09042, Bucks County Listed on the National Register as part of the Newtown Historic District (Boundary Increase: Sycamore Street Extension) on February 25, 1986 S-8 Bridge in Buckingham Township 1905 L.R. 09049, Bucks County S-9 Bridge in Solebury Township 1854 L.R. 09066, Bucks County Listed on the National Register as part of the Carversville Historic District on December 13, 1978. S-10 Lilly Bridge 1832 L.R. 276, Cambria County S-ll Bridge in Cassandra Borough 1832 L.R. 276, Cambria County S-12 Lenape Bridge 1911-1912 L.R. 134, Chester County S-13 County Bridge #101 1918 L.R. 173, Chester County S-l5 Bridge in Tredyffrin Township Unknown L.R. 544, Chester County NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. 1024-0018 (342) Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Owned Highway Bridges Continuation sheet Item number Page 2 S-16 Marshall's Bridge 1903 L.R. -

Power and Policy on the Western Frontier: Struggles For

Daniel P. Barr. A Colony Sprung from Hell: Pittsburgh and the Struggle for Authority on the Western Pennsylvania Frontier, 1744-1794. Kent: Kent State University Press, 2014. 344 pp. $65.00, cloth, ISBN 978-1-60635-190-1. Reviewed by Jessica L. Wallace Published on H-War (November, 2016) Commissioned by Margaret Sankey (Air University) In A Colony Sprung from Hell: Pittsburgh and region, as the French increasingly moved into the the Struggle for Authority on the Western Penn‐ region and Native American groups sought to ei‐ sylvania Frontier, 1744-1794, Daniel P. Barr situ‐ ther remove colonists or exploit their presence for ates the Pittsburgh area in the center of debates their own political ends. From the 1750s forward, on expansion, political control, and military pow‐ charter claims to land were trumped by actual er in the mid-to-late eighteenth century. Barr or‐ military presence and economic power in the re‐ ganizes his book chronologically, from the decade gion. prior to the Seven Years’ War to the Whiskey Re‐ Part 2 deals with British attempts to limit and bellion. Throughout these fve decades, he traces control western expansion through the Proclama‐ the various attempts of Virginia, Pennsylvania, tion Line of 1763 and the creation of Fort Pitt, British imperial officials, and the new American which Indians, Virginians, and Pennsylvanians government to establish authority in western alike objected to, believing it was a sign of more Pennsylvania, highlighting the inability of out‐ British authority and control to come. Part 3 cov‐ siders to effectively exert control over the region, ers the American Revolution through the Whiskey which began as a borderland between colonial Rebellion, tracing how the Revolution affected the settlements and Indian country and in the nine‐ western struggle for authority. -

Chastain-Stark-Vineyard

Chapter XII: Chastain-Stark-Vineyard Last Revised: November 22, 2013 The parents of Sarah {Chastain} Vanderpool were PETER CHASTAIN 1 and REBECCA {STARK} CHASTAIN . Peter was born on November 28, 1795, in Franklin County, Virginia. He prepared his will on January 13, 1852, and died in Lewis Township of Clay County, Indiana, just a few weeks later on February 24, 1852; he is buried in Friendly Grove Cemetery in that township and county. In his will, which was probated on May 26, 1852, Peter Chastain left money to his widow Rebecca and divided his land among his heirs (including his daughter, our Sarah). He also specified that Rebecca was to receive rental income, which indicates that he owned considerable property besides what he had willed to his survivors.2 Rebecca was born on April 10, 1799, in Shelby County, Kentucky, but her date and place of death are not known with certainty. She died after 1880, for she is on the census that year, but searches of obituaries, wills, cemetery records, and death indexes in a number of Indiana counties (particularly in Clay County), have turned up no record of when or where she died. It is likely that her death came sometime during the early 1880s, since Indiana’s statewide index to deaths began in 1882 – though it was incomplete for many years thereafter. We know that on January 3, 1880, Rebecca released her dowry rights to 1 The Chastain family, only mentioned in passing in this chapter, is discussed in detail in a later chapter; refer to a footnote there for an explanation of this surname. -

Heritage Rail Trail Feasibility Study 2017

TOWN OF DEDHAM HERITAGE RAIL TRAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY 2017 PLANNING DEPARTMENT + ENVIRONMENTAL DEPARTMENT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We gratefully recognize the Town of Dedham’s dedicated Planning and Environmental Department’s staff, including Richard McCarthy, Town Planner and Virginia LeClair, Environmental Coordinator, each of whom helped to guide this feasibility study effort. Their commitment to the town and its open space system will yield positive benefits to all as they seek to evaluate projects like this potential rail trail. Special thanks to the many representatives of the Town of Dedham for their commitment to evaluate the feasibility of the Heritage Rail Trail. We also thank the many community members who came out for the public and private forums to express their concerns in person. The recommendations contained in the Heritage Rail Trail Feasibility Study represent our best professional judgment and expertise tempered by the unique perspectives of each of the participants to the process. Cheri Ruane, RLA Vice President Weston & Sampson June 2017 Special thanks to: Virginia LeClair, Environmental Coordinator Richard McCarthy, Town Planner Residents of Dedham Friends of the Dedham Heritage Rail Trail Dedham Taxpayers for Responsible Spending Page | 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Background 2. Community Outreach and Public Process 3. Base Mapping and Existing Conditions 4. Rail Corridor Segments 5. Key Considerations 6. Preliminary Trail Alignment 7. Opinion of Probable Cost 8. Phasing and Implementation 9. Conclusion Page | 2 Introduction and Background Weston & Sampson was selected through a proposal process by the Town of Dedham to complete a Feasibility Study for a proposed Heritage Rail Trail in Dedham, Massachusetts.