The Role of Hepatitis C Virus in Hepatocellular Carcinoma A63

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prevention & Control of Viral Hepatitis Infection

Prevention & Control of Viral Hepatitis Infection: A Strategy for Global Action © World Health Organization 2011. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. Table of contents Disease burden 02 What is viral hepatitis? 05 Prevention & control: a tailored approach 06 Global Achievements 08 Remaining challenges 10 World Health Assembly: a mandate for comprehensive prevention & control 13 WHO goals and strategy -

The Role of Hepatitis C Virus in Hepatocellular Carcinoma U

Viruses in cancer cell plasticity: the role of hepatitis C virus in hepatocellular carcinoma U. Hibner, D. Gregoire To cite this version: U. Hibner, D. Gregoire. Viruses in cancer cell plasticity: the role of hepatitis C virus in hepato- cellular carcinoma. Contemporary Oncology, Termedia Publishing House, 2015, 19 (1A), pp.A62–7. 10.5114/wo.2014.47132. hal-02187396 HAL Id: hal-02187396 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02187396 Submitted on 2 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Review Viruses are considered as causative agents of a significant proportion of human cancers. While the very Viruses in cancer cell plasticity: stringent criteria used for their clas- sification probably lead to an under- estimation, only six human viruses the role of hepatitis C virus are currently classified as oncogenic. In this review we give a brief histor- in hepatocellular carcinoma ical account of the discovery of on- cogenic viruses and then analyse the mechanisms underlying the infectious causes of cancer. We discuss viral strategies that evolved to ensure vi- Urszula Hibner1,2,3, Damien Grégoire1,2,3 rus propagation and spread can alter cellular homeostasis in a way that increases the probability of oncogen- 1Institut de Génétique Moléculaire de Montpellier, CNRS, UMR 5535, Montpellier, France ic transformation and acquisition of 2Université Montpellier 2, Montpellier, France stem cell phenotype. -

Rational Engineering of HCV Vaccines for Humoral Immunity

viruses Review To Include or Occlude: Rational Engineering of HCV Vaccines for Humoral Immunity Felicia Schlotthauer 1,2,†, Joey McGregor 1,2,† and Heidi E Drummer 1,2,3,* 1 Viral Entry and Vaccines Group, Burnet Institute, Melbourne, VIC 3004, Australia; [email protected] (F.S.); [email protected] (J.M.) 2 Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia 3 Department of Microbiology, Monash University, Clayton, VIC 3800, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-392-822-179 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Direct-acting antiviral agents have proven highly effective at treating existing hepatitis C infections but despite their availability most countries will not reach the World Health Organization targets for elimination of HCV by 2030. A prophylactic vaccine remains a high priority. Whilst early vaccines focused largely on generating T cell immunity, attention is now aimed at vaccines that gen- erate humoral immunity, either alone or in combination with T cell-based vaccines. High-resolution structures of hepatitis C viral glycoproteins and their interaction with monoclonal antibodies isolated from both cleared and chronically infected people, together with advances in vaccine technologies, provide new avenues for vaccine development. Keywords: glycoprotein E2; vaccine development; humoral immunity Citation: Schlotthauer, F.; McGregor, J.; Drummer, H.E To Include or 1. Introduction Occlude: Rational Engineering of HCV Vaccines for Humoral Immunity. The development of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAA) with their ability to cure Viruses 2021, 13, 805. https:// infection in >95% of those treated was heralded as the key to eliminating hepatitis C globally. -

Hepatitis A, B, and C: Learn the Differences

Hepatitis A, B, and C: Learn the Differences Hepatitis A Hepatitis B Hepatitis C caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV) caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) HAV is found in the feces (poop) of people with hepa- HBV is found in blood and certain body fluids. The virus is spread HCV is found in blood and certain body fluids. The titis A and is usually spread by close personal contact when blood or body fluid from an infected person enters the body virus is spread when blood or body fluid from an HCV- (including sex or living in the same household). It of a person who is not immune. HBV is spread through having infected person enters another person’s body. HCV can also be spread by eating food or drinking water unprotected sex with an infected person, sharing needles or is spread through sharing needles or “works” when contaminated with HAV. “works” when shooting drugs, exposure to needlesticks or sharps shooting drugs, through exposure to needlesticks on the job, or from an infected mother to her baby during birth. or sharps on the job, or sometimes from an infected How is it spread? Exposure to infected blood in ANY situation can be a risk for mother to her baby during birth. It is possible to trans- transmission. mit HCV during sex, but it is not common. • People who wish to be protected from HAV infection • All infants, children, and teens ages 0 through 18 years There is no vaccine to prevent HCV. -

Understanding Human Astrovirus from Pathogenesis to Treatment

University of Tennessee Health Science Center UTHSC Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations (ETD) College of Graduate Health Sciences 6-2020 Understanding Human Astrovirus from Pathogenesis to Treatment Virginia Hargest University of Tennessee Health Science Center Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uthsc.edu/dissertations Part of the Diseases Commons, Medical Sciences Commons, and the Viruses Commons Recommended Citation Hargest, Virginia (0000-0003-3883-1232), "Understanding Human Astrovirus from Pathogenesis to Treatment" (2020). Theses and Dissertations (ETD). Paper 523. http://dx.doi.org/10.21007/ etd.cghs.2020.0507. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Graduate Health Sciences at UTHSC Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (ETD) by an authorized administrator of UTHSC Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Understanding Human Astrovirus from Pathogenesis to Treatment Abstract While human astroviruses (HAstV) were discovered nearly 45 years ago, these small positive-sense RNA viruses remain critically understudied. These studies provide fundamental new research on astrovirus pathogenesis and disruption of the gut epithelium by induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) following astrovirus infection. Here we characterize HAstV-induced EMT as an upregulation of SNAI1 and VIM with a down regulation of CDH1 and OCLN, loss of cell-cell junctions most notably at 18 hours post-infection (hpi), and loss of cellular polarity by 24 hpi. While active transforming growth factor- (TGF-) increases during HAstV infection, inhibition of TGF- signaling does not hinder EMT induction. However, HAstV-induced EMT does require active viral replication. -

Host Cell Functions in Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Replication Phat X

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Veterinary and Biomedical Science Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, Department of 2016 Host Cell Functions In Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Replication Phat X. Dinh University of Nebraska - Lincoln Anshuman Das University of Nebraska-Lincoln Asit K. Pattnaik University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/vetscipapers Part of the Biochemistry, Biophysics, and Structural Biology Commons, Cell and Developmental Biology Commons, Immunology and Infectious Disease Commons, Medical Sciences Commons, Veterinary Microbiology and Immunobiology Commons, and the Veterinary Pathology and Pathobiology Commons Dinh, Phat X.; Das, Anshuman; and Pattnaik, Asit K., "Host Cell Functions In Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Replication" (2016). Papers in Veterinary and Biomedical Science. 237. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/vetscipapers/237 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Veterinary and Biomedical Science by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Biology and Pathogenesis of Rhabdo and Filoviruses Copyright © 2016 World Scientific Publishing Co Pte Ltd digitalcommons.unl.edu HOST CELL FUNCTIONS IN VESICULAR STOMATITIS VIRUS REPLICATION Phat X. Dinh, Anshuman Das, and Asit K. Pattnaik School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences and the Nebraska Center for Virology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 109 Morrison Life Science Research Center, 4240 Fair Street, Lincoln, * Nebraska 68583, USA E-mail: [email protected] Summary Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), the prototypic rhabdovirus, has been used as an excellent paradigm for understanding the mechanisms of virus replication, pathogenesis, host response to virus infection and also for myriads of studies on cellular and molecular biology. -

Revisiting the Elusive Hepatitis C Vaccine

Editorial Revisiting the Elusive Hepatitis C Vaccine Stephen M. Todryk 1,2,* , Margaret F. Bassendine 2,* and Simon H. Bridge 1,2,* 1 Faculty of Health & Life Sciences, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ST, UK 2 Translational & Clinical Research Institute, The Medical School, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 4HH, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.M.T.); [email protected] (M.F.B.); [email protected] (S.H.B.) The impactful discovery and subsequent characterisation of hepatitis C virus (HCV), an RNA virus of the flavivirus family, led to the awarding of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Harvey J. Alter, Michael Houghton and Charles M. Rice [1]. However, despite the significant advances recognised by this Nobel prize, an effective HCV vaccine remains elusive. The recent success of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, developed with unprecedented speed, has shone a bright light on the vaccination process for protection against viral threats and may provide renewed impetus for the development of vaccines for other viruses. HCV infection remains a major global health problem as approximately three quarters of those infected develop chronic infection, leading to morbidity and mortality due to progressive liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and cancer. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 71.1 million people are living with chronic HCV, resulting in over 400,000 deaths every year. In 2016, the WHO adopted a global strategy with the aim of eliminating viral hepatitis as a public health problem, comprising targets to reduce new viral hepatitis infections by 90% and reduce deaths due to viral hepatitis by 65% by 2030. -

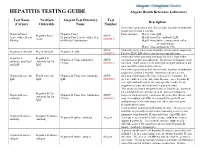

HEPATITIS TESTING GUIDE Alegent Health Reference Laboratory

HEPATITIS TESTING GUIDE Alegent Health Reference Laboratory Test Name NextGen Alegent Test Directory Test Description (Cerner) Orderable Name Number Order when patient has had clinical acute hepatitis of unknown origin for less than 6 months. Hepatitis Panel, Hepatitis Panel Panel includes; Hep A virus, IgM, Hepatitis Panel ARUP Acute with reflex to Hepatitis Panel, Acute with reflex Hep B virus Core antibody, IgM, Acute (0020457) HBsAg to HBsAg Confirmation Hep B virus Surface antigen with reflex to confirmation, Hep C virus antibody by CIA ARUP Order this assay when acute Hepatitis A infection is suspected. Hepatitis A Ab IgM Hep A Ab IgM Hepatitis A, IgM (0020093) Positive HAV IgM shows current or recent infection. Order only when assessing immunity for HAV from either Hepatitis A Hepatitis A Hepatitis A Virus Antibodies ARUP vaccination or previous infection. Do not use to diagnose acute antibody, total (IgG Antibody IgG & (Total) (0020591) infection. Total assay detects both IgG and IgM antibodies but and IgM IgM does not differentiate between them. Order when patient has had clinical acute hepatitis of unknown origin for less than 6 months. Positivity indicates recent Hepatitis B core Ab Hep B Core Ab Hepatitis B Virus Core Antibody, ARUP infection with hepatitis B virus, with onset < 6 months. It's IgM IgM IgM (0020092) presence indicates acute infection. In some cases, hepatitis B core IgM antibody may be the only specific marker for the diagnosis of acute infection with hepatitis B virus. This assay does not distinguish between Total B core antibody IgG and IgM detected before or at the onset of symptoms; Hepatitis B Core Hepatitis B core Hepatitis B Virus Core Antibodies ARUP however, such reactivity can persist for years after illness, and Antibody IgG & antibody (Total) (0020091) may even outlast anti-HBs. -

Can a Virus Cause Cancer: a Look Into the History and Significance of Oncoviruses

UC Berkeley Berkeley Scientific Journal Title Can A Virus Cause Cancer: A Look Into The History And Significance Of Oncoviruses Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6c57612p Journal Berkeley Scientific Journal, 14(1) ISSN 1097-0967 Author Rwazavian, Niema Publication Date 2011 DOI 10.5070/BS3141007638 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CA N A VIRU S CA U S E CA NCER ? A LOOK IN T O T HE HI st ORY A ND SIGNIFIC A NCE OF ONCO V IRU S E S Niema Rwazavian The IMPORTANC E OF ONCOVIRUS E S (van Epps 2005). Although many in the scientific Cancer, a disease caused by unregulated cell community were unconvinced of the role of viruses in growth, is often attributed to chemical carcinogens cancer, research on the subject nevertheless continued. (e.g. tobacco), hormonal imbalances (e.g. high levels of In 1933, Richard Shope discovered the first mammalian estrogen), or genetics (e.g. breast cancer susceptibility oncovirus, cottontail rabbit papillomavirus (CRPV), gene 1). While cancer can originate from any number which could infect cottontail rabbits, and in 1936, John of sources, many people fail to recognize another Bittner discovered the mouse mammary tumor virus important etiology: oncoviruses, or cancer-causing (MMTV), which could be transmitted from mothers to pups via breast milk (Javier and Butle 2008). By the 1960s, with the additional “…despite limited awareness, oncoviruses are discovery of the murine leukemia BSJ virus (MLV) in mice and the SV40 nevertheless important because they represent virus in rhesus monkeys, researchers over 17% of the global cancer burden.” began to acknowledge the possibility that viruses could be linked to human cancers as well. -

A Novel Method to Rescue and Culture Duck Astrovirus Type 1 in Vitro

Zhang et al. Virology Journal (2019) 16:112 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-019-1218-5 RESEARCH Open Access A novel method to rescue and culture duck Astrovirus type 1 in vitro Ruihua Zhang1,2†, Jingjing Lan1,2†, Haie Li1†, Junhao Chen1,2, Yupeng Yang1,2, Shaoli Lin1, Zhijing Xie1,2 and Shijin Jiang1,2* Abstract Background: Reverse genetics systems enable the manipulation of viral genomes and therefore serve as robust reverse genetic tools to study RNA viruses. A DNA-launched rescue system initiates the transcription of viral genomic cDNA from eukaryotic promoter in transfected cells, generating homogenous RNA transcripts in vitro and thus enhancing virus rescue efficiency. As one of the hazardous pathogens to ducklings, the current knowledge of the pathogenesis of duck astrovirus type 1 (DAstV-1) is limited. The construction of a DNA- launched rescue system can help to accelerate the study of the virus pathogenesis. However, there is no report of such a system for DAstV-1. Methods: In this study, a DNA-launched infectious clone of DAstV-1 was constructed from a cDNA plasmid, which contains a viral cDNA sequence flanked by hammerhead ribozyme (HamRz) and a hepatitis delta virus ribozyme (HdvRz) sequence at both terminals of the viral genome. A silent nucleotide mutation creating a Bgl II site in the ORF2 gene was made to distinguish the rescued virus (rDAstV-1) from the parental virus (pDAstV-1). Immunofluorescence assay (IFA) and western blot were conducted for rescued virus identification in duck embryo fibroblast (DEF) cells pre-treated with trypsin. The growth characteristics of rDAstV-1 and pDAstV-1 in DEF cells and the tissue tropism in 2-day-old ducklings of rDAstV-1 and pDAstV-1 were determined. -

The Pivotal Role of Viruses in the Pathogeny of Chronic

viruses Case Report The Pivotal Role of Viruses in the Pathogeny of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Monoclonal (Type 1) IgG K Cryoglobulinemia and Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Diagnosis in the Course of a Human Metapneumovirus Infection Jérémy Barben * , Alain Putot , Anca-Maria Mihai, Jérémie Vovelle and Patrick Manckoundia Geriatrics Internal Medicine Department, University Hospital of Dijon, Hôpital de Champmaillot 2, Rue Jules Violle—BP 87 909—21079 DIJON CEDEX, France; [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (A.-M.M.); [email protected] (J.V.); [email protected] (P.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-380-29-39-70; Fax: +33-380-39-36-21 Abstract: Background: Type-1 cryoglobulinemia (CG) is a rare disease associated with B-cell lym- phoproliferative disorder. Some viral infections, such as Epstein–Barr Virus infections, are known to cause malignant lymphoproliferation, like certain B-cell lymphomas. However, their role in the pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is still debatable. Here, we report a unique case of Type-1 CG associated to a CLL transformation diagnosed in the course of a human metap- neumovirus (hMPV) infection. Case presentation: A 91-year-old man was initially hospitalized for Citation: Barben, J.; Putot, A.; Mihai, A.-M.; Vovelle, J.; Manckoundia, P. delirium. In a context of febrile rhinorrhea, the diagnosis of hMPV infection was made by molecular The Pivotal Role of Viruses in the assay (RT-PCR) on nasopharyngeal swab. Owing to hyperlymphocytosis that developed during the Pathogeny of Chronic Lymphocytic course of the infection and unexplained peripheral neuropathy, a type-1 IgG Kappa CG secondary to Leukemia: Monoclonal (Type 1) IgG a CLL was diagnosed. -

Virus-Mediated Cell-Cell Fusion

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Virus-Mediated Cell-Cell Fusion Héloïse Leroy 1,2,3, Mingyu Han 1,2,3 , Marie Woottum 1,2,3 , Lucie Bracq 4 , Jérôme Bouchet 5 , Maorong Xie 6 and Serge Benichou 1,2,3,* 1 Institut Cochin, Inserm U1016, 75014 Paris, France; [email protected] (H.L.); [email protected] (M.H.); [email protected] (M.W.) 2 Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique CNRS, UMR8104, 75014 Paris, France 3 Faculty of Health, University of Paris, 75014 Paris, France 4 Global Health Institute, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland; lucie.bracq@epfl.ch 5 Laboratory Orofacial Pathologies, Imaging and Biotherapies UR2496, University of Paris, 92120 Montrouge, France; [email protected] 6 Division of Infection and Immunity, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 November 2020; Accepted: 14 December 2020; Published: 17 December 2020 Abstract: Cell-cell fusion between eukaryotic cells is a general process involved in many physiological and pathological conditions, including infections by bacteria, parasites, and viruses. As obligate intracellular pathogens, viruses use intracellular machineries and pathways for efficient replication in their host target cells. Interestingly, certain viruses, and, more especially, enveloped viruses belonging to different viral families and including human pathogens, can mediate cell-cell fusion between infected cells and neighboring non-infected cells. Depending of the cellular environment and tissue organization, this virus-mediated cell-cell fusion leads to the merge of membrane and cytoplasm contents and formation of multinucleated cells, also called syncytia, that can express high amount of viral antigens in tissues and organs of infected hosts.