Lgbtqtheme-Miami.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FREEDOM PRIMER No.L

FREEDOM PRIMER No.l The Convention Challenge and The Freedom Vote THE CHALLENGE AT THE DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL CONVENTION What Was The Democratic National Convention? The Democratic National Convention was a big meeting held by the National Democratic Party at Atlantic City in August. People who represent the Party came to the Convention from every state in the country. They came to decide who would be the candidates of the Democratic Party for President and Vice-President of the United States in the election this year on November 3rd. They also came to decide what the Platform of the National Democratic Party would be. The Platform is a paper that says what the Party thinks should be done about things like Housing, Education, Welfare, and Civil Rights. Why Did The Freedom Democratic Party Go To The Convention? The Freedom Democratic Party (FDP) sent a delegation of 68 people to the Convention. These people wanted to represent you at the Convention. They said that they should be seated at the Convention instead of the people sent by the Regular Democratic Party of Mississippi. The Regular Democratic Party of Mississippi only has white people in it. But the Freedom Democratic Party is open to all people -- black and white. So the delegates from the Freedom Democratic Party told the Convention ±t was the real representative of all the people of Mississippi. How Was The Regular Democratic Party Delegation Chosen? The Regular Democratic Party of Mississippi also sent 68 -^ people to the Convention in Atlantic City. But these people were not chosen by all the people of Mississippi. -

May/June 2019

Today’s Fern May/June 2019 Publication of the 100 Ladies of Deering, a philanthropic circle of the Deering Estate Foundation The 100 Ladies Again Undertake a Whirlwind Month Like the citizens of Sitges, Spain, the 100 Ladies of Deering are devoted to the preservation of a historic landmark once owned by Charles Deering. Our efforts to conserve and preserve this magniBicent estate located in our backyard, unites us with citizens of Sitges on the other side of the Atlantic. Those who went on our fundraising cruise in April experienced the small town of Sitges’ gratitude to the memory of the Town’s Adopted Son, Charles Deering. One hundred and ten years from the time Deering Birst visited Sitges, we were welcomed like long lost family with choral songs, champagne, and stories of the beloved adopted son’s vision, philanthropy and economic contributions. The stories we share are similar, like here in Cutler, Deering built an “architectural gem” in Sitges and Billed it at the time President Maria and husband David toast a very successful fundraiser with art by renowned artists. The town’s warm cruise to Spain…with side trips to Sitges and Tamarit. welcome given to us was inspiring because it demonstrates their deep “If we love, and we do, appreciation for Charles Deering’s vision and legacy which we both strive to what Charles Deering preserve. I highly encourage you to participate in any future trips where we seek to bequeathed us…If we further understand Charles Deering’s legacy, whether here in Miami, Chicago or consider it to be so Spain. -

Producing a Past: Cyrus Mccormick's Reaper from Heritage to History

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2014 Producing a Past: Cyrus Mccormick's Reaper from Heritage to History Daniel Peter Ott Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ott, Daniel Peter, "Producing a Past: Cyrus Mccormick's Reaper from Heritage to History" (2014). Dissertations. 1486. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2014 Daniel Peter Ott LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO PRODUCING A PAST: CYRUS MCCORMICK’S REAPER FROM HERITAGE TO HISTORY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY JOINT PROGRAM IN AMERICAN HISTORY / PUBLIC HISTORY BY DANIEL PETER OTT CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2015 Copyright by Daniel Ott, 2015 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is the result of four years of work as a graduate student at Loyola University Chicago, but is the scholarly culmination of my love of history which began more than a decade before I moved to Chicago. At no point was I ever alone on this journey, always inspired and supported by a large cast of teachers, professors, colleagues, co-workers, friends and family. I am indebted to them all for making this dissertation possible, and for supporting my personal and scholarly growth. -

Glenda Russell & Renee Morgan

OUT OF THE SHADOWS: 1969 A Timeline of Boulder LGBT History Since the Stonewall riots in 1969, the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people BOULDER have been advanced in many ways and in places small and large. Much is known about the struggle and advances in LGBT rights that have taken place on national and state stages. Much less is known about the path toward equal rights for LGBT people in Boulder. This is Boulder’s story. COLORADO Compiled by Glenda Russell & Renee Morgan Sponsored by Designed by 1969 NYC Stonewall Riots NATIONAL 1970s 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1974 1970 1978 Referendum: Boulder Gay Liberation Lesbian Caucus and Sexual Orientation Front is formed at CU Boulder Gay Liberation is removed from create stir with Boulder’s Human Gay Blue Jeans Day Rights Ordinance Recall election: Tim Fuller is recalled and Pen Tate barely survives recall effort Same-sex couples are ejected from down- 1976 town bars for dancing Gay and Lesbian together; protests follow class is taught Monthly dances at Jack Kerouac School at CU Hidden Valley Ranch Maven Productions of Disembodied draw hundreds produces its first Poetics is formed at concert, Cris Naropa Institute Williamson at Tulagi’ 1979 After evicting same-sex couples dancing, Isa- dora’s picketed; their sign zapped 1971 Boulder Gay Liberation Front publishes first issue of monthly newsletter, Gayly Planet 1973 Boulder City Council adopts Human Rights Ordinance, including sexual orientation 1975 Boulder County Clerk 1972 Clela Rorex grants Boulder -

Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race the Opportunity Agenda

Opinion Research & Media Content Analysis Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race The Opportunity Agenda Acknowledgments This research was conducted by Loren Siegel (Executive Summary, What Americans Think about LGBT People, Rights and Issues: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Public Opinion, and Coverage of LGBT Issues in African American Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); Elena Shore, Editor/Latino Media Monitor of New America Media (Coverage of LGBT Issues in Latino Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); and Cheryl Contee, Austen Levihn- Coon, Kelly Rand, Adriana Dakin, and Catherine Saddlemire of Fission Strategy (Online Discourse about LGBT Issues in African American and Latino Communities: An Analysis of Web 2.0 Content). Loren Siegel acted as Editor-at-Large of the report, with assistance from staff of The Opportunity Agenda. Christopher Moore designed the report. The Opportunity Agenda’s research on the intersection of LGBT rights and racial justice is funded by the Arcus Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are those of The Opportunity Agenda. Special thanks to those who contributed to this project, including Sharda Sekaran, Shareeza Bhola, Rashad Robinson, Kenyon Farrow, Juan Battle, Sharon Lettman, Donna Payne, and Urvashi Vaid. About The Opportunity Agenda The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2004 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds, and policy over time, the organization works with social justice groups, leaders, and movements to advance solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and corresponding solutions; uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion; and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives. -

2020-2021 EVENTS for the Latest Events, Visit Gaydesertguide.LGBT 2020-2021 EVENTS

2020-2021 EVENTS For the latest Events, Visit GayDesertGuide.LGBT 2020-2021 EVENTS Canceled Dining Out for Life Oct. 17 Palm Springs Equality Awards Postponed Evening Under the Stars Oct. 22-25 PS International Dance Festival New Date Red Dress/Dress Red (3/20/21) Oct. 23-25 Stagecoach June 9 Outstanding Voices Oct. 24 Desert AIDS Walk June 13 Stonewall Humanitarian Awards Oct. 25 Opera In the Park June 16-22 PS International ShortFest Oct. 29-Nov. 1 PS Leather Pride June 27 Global Pride 2020 Oct. 30 LGBTQ Center’s Center Stage July 4 AAP-Food Samaritians 4th of July Party Oct. 30-Nov. 2 White Party July 11 Harvey Milk Diversity Breakfast Oct. 31 Halloween on Arenas July 16-22 Gay Wine Week, Sonoma County Nov. 6 - 8 Palm Springs Pride Aug. 7-9 Splash House Weekend 1 Canceled Diversity DHS Pride Festival Aug. 14-16 Splash House Weekend 2 Nov. 20 Transgender Day of Rememberance Aug. 20-23 Big Bear Romp Nov. 21 California Dreamin’ Concert Sept. 10-13 ANA Inspiration 2020 Dec. 1 Everyday Heroes / World AIDs Day Sept. 16-20 Club Skirts Dinah Shore Weekend 2020 Dec. 2 Annual Joint Chamber of Commerce Mixer Sept. 23 Taste of Palm Springs/Business Expo Dec. 8-13 Barry Manilow’s A Gift of Love Concert Sept. 25-29 American Documentary Film Festival Jan. 7 PS International Film Fest Gala 2021 Oct. 3 Palm Springs Le Diner en Blanc Jan. 8-18 PS International Film Festival 2021 Oct. 4-7 Jewish Film Festival Oct. 9-11 Coachella Weekend 1 Oct. -

The Trouble with White Feminism: Whiteness, Digital Feminism and the Intersectional Internet

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 2016 The Trouble with White Feminism: Whiteness, Digital Feminism and the Intersectional Internet Jessie Daniels Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/194 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “The Trouble with White Feminism: Whiteness, Digital Feminism and the Intersectional Internet” by Jessie Daniels, PhD Professor, Sociology Hunter College and The Graduate Center, CUNY 2180 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10035 email: [email protected] or [email protected] Submitted for consideration to the volume The Intersectional Internet, Section Two: Cultural Values in the Machine (2016) PRE-PRINT VERSION, 16 FEBRUARY 2015 ABSTRACT (210): In August, 2013 Mikki Kendall, writer and pop culture analyst, started the hashtag #SolidarityisforWhiteWomen as a form of cyberfeminist activism directed at the predominantly white feminist activists and bloggers at sites like Feministing, Jezebel and Pandagon who failed to acknowledge the racist, sexist behavior of one their frequent contributors. Kendall’s hashtag activism quickly began trending and reignited a discussion about the trouble with white feminism. A number of journalists have excoriated Kendall specifically, and women of color more generally, for contributing to a “toxic” form of feminism. Yet what remains unquestioned in these journalistic accounts and in the scholarship to date, is the dominance of white women as architects and defenders of a framework of white feminism – not just in the second wave but today, in the digital era. -

LGBTQ History Timeline

Timeline – University of Miami’s LGBTQ History Milestones 1975 · April: Gay Alliance was formed in early April 1975. Ana Roca and Buzz Stearns were the prime movers of the organization. · October: Gay Alliance organized the first social event attended by 125 guests. They were recognized as an official UM organization. Edward Graziani was listed as president. Professor Marian Grabowski, Rev. Tom Crowder (UM chaplain), and Open Door were listed as supporters. UM program “Open Door” was a gathering place for students staffed by student volunteers selected and trained by the Counselling Center psychologists. 1977 · February: Professor Marian Grabowski, who had a column titled “Across Mrs. G’s Desk” in TMH, wrote an essay titled “Gays Deserve Same Rights, Justice, and Liberty.” · June: Anita Bryant’s anti-gay rights movement emerged and remained a hot topic among students for the next few years. Her name appeared in Ibis from 1978 to 1980. 1978 · April: On-campus celebration of the National Gay Blue Jeans Day raised an exchange of opinions by gay and straight students. · The last time TMH listed a program by Gay Alliance was October 10, 1978. 1980 · February: Ad in THM shows that UM provided counseling on homosexuality for students. 1982 · April: TMH’s supportive coverage of gay lifestyle was criticized by one student and two students responded supporting the newspaper. 1985 · October: Sal O’Neal, UM Senior, wrote the article “Gay Student Seeks to Inform” about the gay community at UM and in Miami. He also wrote that Gay Alliance flamed out in 1977 after the graduation of the leader Dan Abraham. -

Twohearts-Matching-G

2722 NE 20th Court Fort Lauderdale, FL 33305 Double your (philanthropic) pleasure Between February 1 - 14, 2013 Help us turn $50,000 into $100,000+ are better than A matching gift program for Valentine’s Day Our Fund will match gifts from new donors1 or increased gifts2 from current donors who make a gift of $500.00 to a local non-profit organization serving the LGBT community in South Florida11 The Following restrictions apply: 1. A “New Donor” is defined as a donor who has not contributed to the organization within the past 18 months. 2. An “Increased Gift” is defined as any new amount over and above the amount a donor has given in the past twelve months. 3. Gifts must be received between February 1st and February 14th, 2013 only. 4. Donor’s gift must be at least $500. 5. Maximum matching gift from Our Fund will be $500 per donor. Donors may contribute to multiple quali- fied organizations. 6. Maximum amount of matching gifts to each non-profit organization will be $5,000. 7. Maximum of $50,000 in matching gifts have been committed. Program expires on February 14, 2013 or when $50,000 in matching gifts have been committed. 8. Gifts accepted in order of receipt and must accompany this form. 9. Donor’s portion and matching gift portions to be distributed to non-profits at the end of the program. 10. Eligible participating organizations will be incorporated in Florida, provide direct services to the LGBT com- munity in Florida only and are very active in South Florida (Palm Beach, Broward and Miami-Dade Counties). -

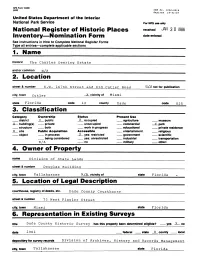

6. Representation in Existing Surveys

NFS Form 10-900 (3-82) OHB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register off Historic Places received JAN 3 0 1986 Inventory — Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries — complete applicable sections _______________ 1. Name historic The Charles Peering Estate and or common N/A 2. Location street & number S.W. 167th Street and Old Cutler Road not for publication city, town Cutler _X_ vicinity of Miami state Florida code 12 county Dade code 025 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district _X _ public X occupied agriculture __ museum JL_ building(s) private unoccupied commercial ^K_park structure both work in progress educational private residence JL_ site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A no military Other; 4. Owner off Property name Division of State Lands street & number Douglas Building city, town Tallahassee N/A vicinity of state Florida 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. street & number 73 West Flagler Street city, town Miami state Florida 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Dade County Historic Survey has this property been determined eligible? yes X no date J9'81 federal state X county local depository for survey records Division of Archives , History and Records Management city, town Tallahassee ____________ state Florida_____ 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site x good ruins ^ altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Charles Deering Estate is one of the finest bayfront properties in Dade County. -

ROOTS in CHICAGO One Hundred Years Deep

ROOTS IN CHICAGO One Hundred Years Deep 1847-^1947 ROOTS IN CHICAGO One Hundred Years Deep 1847-1947 ^ch. Illl^^; i- ^'*k>.«,''''*!a An illustrated map of Chicago, 1847, with which have been combined historic developments leading up to and including the Chicago Fire of 1871. ^^ m .4 1. First McCormick Factory—1847 > ;**!!>*>>, 2. Old Fort Dearborn -1847 L^tim_^wr """ ,4. First Permanent School—1845] 5. Water Works-1854 13. First Court House—1835 .IIIIIIIIUIIIIIIIII! john mckee -JJ ^^^^J ^^^J ^^^^ ^W^^v^A^ V^^^^J ^^LAV ^^^M ^^1^1 ^^^AJ ^^^W ^^^V ^^^^m U-J^^-JS u"''-"--'''^ Cilaajij^ f.nU Infi ,1)1 M v3 ^- ••^ •c> c;^ '-a -.•^ ••••.>« tnick Theological Seminary Chicago Fire-1871 >,»ii)iiiinmiiiiiin!i HI I'nTiTn •'•••••ll 2 fe n^ir • ••I m " ™ 11 Enlarged Factory—1871 Prefiace THIS YEAR IS THE 100th Anniversary of an event which has played an important part in the building of Chi cago. In late summer of 1847 my grandfather, Cyrus Hall McCormick, came to Chicago to manufacture an improved model of the reaper he had invented and publicly demonstrated sixteen years earlier in Virginia. The little reaper plant which he founded, and de veloped through the years with the assistance of his two brothers, is now represented in the Chicago area by six International Harvester Company factories, a manufacturing research center, a central school for Harvester personnel, a Harvester printing plant, gen eral offices, and a number of motor truck sales branches. More than 30,000 Harvester men and women are now employed in Chicago. It is fitting at this time to pay tribute to the man whose genius laid the groundwork for Harvester's ex tensive operations in Chicago as well as in the rest of the world. -

Outher Stories

A Guide for Reporting on LGBTQ People in Florida OUTHER Una guía para asistir en el S STORIES N reportaje sobre personas LGBTQ en la Florida English Español Letters from GLAAD & Equality Florida Mensaje de GLAAD & Equality Florida 03 19 Getting Started Introducción 04 20 Terms & Definitions Términos y definiciones 05 21 Florida's LGBTQ History Cronología de la historia de la comunidad LGBTQ de la Florida 06 21 In Focus: Pulse Nightclub En foco: Discoteca Pulse 10 22 Terms to Avoid Términos que se deben evitar 12 26 Best Practices Prácticas óptimas 14 28 Pitfalls to Avoid Errores que se deben evitar 15 30 Story Ideas Ideas para notas periodísticas 16 32 Organizations Organizaciones 17 33 GLAAD's Assistance El equipo de GLAAD 18 34 Cover photos courtesy of (from top left): Equality Florida, The Rainbow Family & Friends of The Villages, Equality Florida, Equality Florida, Winnie Miles & Carolyn Allen, The Rainbow Family & Friends of The Villages GLAAD Southern Stories A Guide for Reporting on LGBTQ People in Florida When GLAAD’s first Accelerating Acceptance report revealed that levels of discomfort towards the LGBTQ community are as high as 43% in America—and spike to 61% in the U.S. South—we knew we had to act. This annual study by GLAAD and our partners at The Harris Poll, which measures Americans' attitudes towards the LGBTQ community, shows that while comfort levels may be rising, more than half of Southerners believe their peers remain uncomfortable around LGBTQ people in various day-to-day situations, such as seeing a same-sex couple holding hands or learning a family member is LGBTQ.