Producing a Past: Cyrus Mccormick's Reaper from Heritage to History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Stable Farm, Munstone, Hereford, Hr1 3Ah

=Auctioneers= =Estate Agents= H.J. Pugh & Co. =Valuers= STABLE FARM, MUNSTONE, HEREFORD, HR1 3AH Dispersal sale of the renowned Colin Powell collection of FERGUSON TRACTORS, IMPLEMENTS, SPARES AND LITERATURE th SATURDAY 29 SEPTEMBER. 10.00AM BUYERS PREMIUM 5% + VAT. ONLINE BIDDING VIA EASYLIVE AUCTIONS Newmarket House, Market Street, Ledbury. Herefordshire. HR8 2AQ. Tel: 01531 631122. Fax: 01531 631818 Email: [email protected] CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. All prospective purchasers to register to bid and give in their name, address and telephone number, in default of which the lot or lots purchased may be immediately put up again and re-sold 2. The highest bidder to be the buyer. If any dispute arises regarding any bidding the Lot, at the sole discretion of the auctioneers, to be put up and sold again. 3. The bidding to be regulated by the auctioneer. 4. In the case of Lots upon which there is a reserve, the auctioneer shall have the right to bid on behalf of the Vendor. 5. No Lots to be transferable and all accounts to be settled at the close of the sale. 6. The lots to be taken away whether genuine and authentic or not, with all faults and errors of every description and to be at the risk of the purchaser immediately after the fall of the hammer but must be paid for in full before the property in the goods passes to the buyer. The auctioneer will not hold himself responsible for the incorrect description or authenticity of or any fault or defect in any lot and makes no warranty. -

Toys and Action Figures in Stock

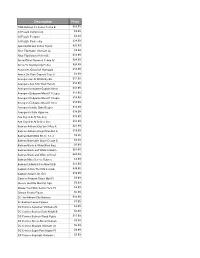

Description Price 1966 Batman Tv Series To the B $29.99 3d Puzzle Dump truck $9.99 3d Puzzle Penguin $4.49 3d Puzzle Pirate ship $24.99 Ajani Goldmane Action Figure $26.99 Alice Ttlg Hatter Vinimate (C: $4.99 Alice Ttlg Select Af Asst (C: $14.99 Arrow Oliver Queen & Totem Af $24.99 Arrow Tv Starling City Police $24.99 Assassins Creed S1 Hornigold $18.99 Attack On Titan Capsule Toys S $3.99 Avengers 6in Af W/Infinity Sto $12.99 Avengers Aou 12in Titan Hero C $14.99 Avengers Endgame Captain Ameri $34.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Iron $14.99 Avengers Infinite Grim Reaper $14.99 Avengers Infinite Hyperion $14.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Axe Cop $15.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Dr Doo Doo $12.99 Batman Arkham City Ser 3 Ras A $21.99 Batman Arkham Knight Man Bat A $19.99 Batman Batmobile Kit (C: 1-1-3 $9.95 Batman Batmobile Super Dough D $8.99 Batman Black & White Blind Bag $5.99 Batman Black and White Af Batm $24.99 Batman Black and White Af Hush $24.99 Batman Mixed Loose Figures $3.99 Batman Unlimited 6-In New 52 B $23.99 Captain Action Thor Dlx Costum $39.95 Captain Action's Dr. Evil $19.99 Cartoon Network Titans Mini Fi $5.99 Classic Godzilla Mini Fig 24pc $5.99 Create Your Own Comic Hero Px $4.99 Creepy Freaks Figure $0.99 DC 4in Arkham City Batman $14.99 Dc Batman Loose Figures $7.99 DC Comics Aquaman Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Batman Dark Knight B $6.99 DC Comics Batman Wood Figure $11.99 DC Comics Green Arrow Vinimate $9.99 DC Comics Shazam Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Super -

Batman Takes Parade by Storm (Thesis by Jared Goodrich)

Jared Goodrich Batman Takes Parade By Storm (How Comic Book Culture Shaped a Small City’s Halloween parade) History Research Seminar Spring 2020 1 On Saturday, October 26th, 2019, the participants lined up to begin of the Rutland Halloween Parade. 10,000 people came to the small city of Rutland to view the famed Halloween parade for its 60th year. Over 72 floats had participated and 1700 people led by the Skelly Dancers. School floats with specific themes to the Star Wars non-profit organization the 501st Legion to droves and rows of different Batman themed floats marched throughout the city to celebrate this joyous occasion. There have been many narratives told about this historic Halloween parade. One specific example can be found on the Rutland Historical Society’s website, which is the documentary called Rutland Halloween Parade Hijinks and History by B. Burge. The standard narrative told is that on Halloween night in 1959, the Rutland area was host to its first Halloween parade, and it was a grand show in its first year. The story continues that a man by the name of Tom Fagan loved what he saw and went to his friend John Cioffredi, who was the superintendent of the Rutland Recreation Department, and offered to make the parade better the next year. When planning for the next year, Fagan suggested that Batman be a part of the parade. By Halloween of 1961, Batman was running the parade in Rutland, and this would be the start to exciting times for the Rutland Halloween parade.1 Five years into the parade, the parade was the most popular it had ever been, and by 1970 had been featured in Marvel comics Avengers Number 83, which would start a major event later in comic book history. -

Creating Farm Foundation 47 Chapter 4: Hiring Henry C

© 2007 by Farm Foundation This book was published by Farm Foundation for nonprofit educational purposes. Farm Foundation is a non-profit organization working to improve the economic and social well being of U.S. agriculture, the food system and rural communities by serving as a catalyst to assist private- and public-sector decision makers in identifying and understanding forces that will shape the future. ISBN: 978-0-615-17375-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2007940452 Cover design by Howard Vitek Page design by Patricia Frey No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher: Farm Foundation 1301 West 22nd Street, Suite 615 Oak Brook, Illinois 60523 Web site: www.farmfoundation.org First edition. Published 2007 Table of Contents R.J. Hildreth – A Tribute v Prologue vii Chapter 1: Legge and Lowden 1 Chapter 2: Events Leading to the Founding of Farm Foundation 29 Chapter 3: Creating Farm Foundation 47 Chapter 4: Hiring Henry C. Taylor 63 Chapter 5: The Taylor Years 69 Chapter 6: The Birth and Growth of Committees 89 Chapter 7: National Public Policy Education Committee 107 Chapter 8: Farm Foundation Programming in the 1950s and 1960s 133 Chapter 9: Farm Foundation Round Table 141 Chapter 10: The Hildreth Legacy: Farm Foundation Programming in the 1970s and 1980s 153 Chapter 11: The Armbruster Era: Strategic Planning and Programming 1991-2007 169 Chapter 12: Farm Foundation’s Financial History 181 Chapter 13: The Future 197 Acknowledgments 205 Endnotes 207 Appendix 223 About the Authors 237 R.J. -

Feuling® Reaper® Series Camshafts for Milwaukee Eight Grinds: 405, 465, 508, 521

FEULING® REAPER® SERIES CAMSHAFTS FOR MILWAUKEE EIGHT GRINDS: 405, 465, 508, 521, 592 • FEULING® REAPER® camshafts have wide lobe separations producing very wide power bands • Smooth camshaft lobe ramps are easier on valve-train components eliminating excessive valve-train noise and wear. • Better Throttle Response - Increased MPG - Easy Starting - Unique Idle Sound • Made in U.S.A. 405 CAM - A workhorse, producing a wide powerband increasing torque and HP throughout the entire RPM range when compared to stock. Direct bolt in replacement for Milwaukee Eight engines, can be used with stock valve springs, pushrods, lifters and exhaust. Will respond well with slip-on mufflers and or complete exhaust system and a high flow air cleaner. Note Feuling recommends using mufflers with smaller cores for best lower RPM power and pull. Part # 1340 Valve Lift Open Close Duration @ 50" lift @ TDC Lobe Centerline Intake .395 4 ATDC 24 ABDC 200 .068 103 Exhaust .405 36 BBDC 11 BTDC 205 .049 108 RPM range: 1,700 - 5,700 Grind: 405 Overlap: 7 465 CAM - The 465 Reaper is an accelerator, producing solid bottom end performance with substantial gains above 2,800 RPM when compared to stock. This direct bolt in replacement for Milwaukee Eight engines can be used with stock valve springs, pushrods, lifters and exhaust. Will respond well with slip-on mufflers and or performance exhaust system and air cleaner. Use of performance valve-springs is not required but may result in a quieter, smoother running valve-train See Feuling #1107. This cam will also respond well with increased bore and or compression Part #1343 Valve Lift Open Close Duration @ 50" lift @ TDC Lobe Centerline Intake .445 4 BTDC 23 ABDC 207 .100 99.5 Exhaust .465 50 BBDC 6 ATDC 236 .100 112 RPM range: 1,850 - 5,950 Grind: 465 Overlap: 10 521 CAM - Aggressive pulling power with a "nasty" sound, the REAPER 521 grind will shine in 114" and larger cubic inch engines with added compression ratio. -

Cutting Parts

GENUINE NEW HOLLAND CUTTING PARTS. Combines | Disc Mowers Draper Headers | Mowers Mower-Conditioners | Windrowers All-Makes | Kits WORK SMARTER WITH MY SHED™ AND MY SHED MOBILE APP 2.1. Google Play™ for Android™ Apple® Store for iPhone® WE KNOW WHAT YOUR MACHINE’S MADE OF. The Partstore has everything you need to keep your equipment up and running. Now you can easily store your machine models to access parts with My Shed and My Shed Mobile App, 2.1. My Shed offers: • Machine Management: Enter serial • Toolboxes: Oil/fluid selector and number, hours and notes battery finder • Parts Manuals: Access assembly • Machine Info: Product alerts diagrams and create part pick lists and videos • 24/7 Dealer Connection: Email part pick lists to a dealer SELECT US – YOUR LOCAL DEALER – ON PARTSTORE: WWW.PARTSTORE.AGRICULTURE.NEWHOLLAND.COM www.newholland.com/na ©2015 CNH Industrial America LLC. All rights reserved. New Holland is a trademark registered in the United States and many other countries, owned by or licensed to CNH Industrial N.V., its subsidiaries or affiliates. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CUTTING PARTS DISC MOWER KNIVES FOR TODAY’S 9–15 Blades, Kits DEMANDING DISK MOWER/ MOWER-CONDITIONERS SICKLE BAR MOWER APPLICATIONS 16–23 Knife Assemblies, Kits New Holland Original Equipment Cutting Parts are designed and manufactured for the finest agricultural harvesting equipment available today. Whether for the New Holland Mower, HAY MACHINES MY SHED Mower-Conditioner, Windrower or Combine Header, we’ve designed knife sections and knife assem blies to go the 24–27 Knife Assemblies, Kits MOBILE APP 2.1. -

Download Video Products and Analyze Mission Results from Reapers Or Any Other Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Aircraft Supported by a Distributed Crew

Disclaimer The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the US Government. 2 The MQ-9 Reaper Remotely Piloted Aircraft: Humans and Machines in Action by Timothy M. Cullen Submitted to the Engineering Systems Division on August 12, 2011 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering Systems: Technology, Management, and Policy Abstract Remotely piloted aircraft and the people that control them are changing how the US military operates aircraft and those who fly, yet few know what “drone” operators actually do, why they do what they do, or how they shape and reflect remote air warfare and human-machine relationships. What do the remote operators and intelligence personnel know during missions to “protect and avenge” coalition forces in Iraq and Afghanistan and how do they go about knowing what they know? In an ethnographic and historical analysis of the Air Force’s preeminent weapon system for the counterinsurgencies in the two countries, this study describes how social, technical, and cognitive factors mutually constitute remote air operations in war. Armed with perspectives and methods developed in the fields of the history of technology, sociology of technology, and cognitive anthropology, the author, an Air Force fighter pilot, describes how distributed crews represent, transform, and propagate information to find and kill targets and traces the observed human and machine interactions to policy assumptions, professional identities, employment concepts, and technical tools. In doing so, he shows how the people, practices, and machines associated with remotely piloted aircraft have been oriented to and conditioned by trust in automation, experience, skill, and social interactions and how they have influenced and reflected the evolving operational environment, encompassing organizations, and communities of practice. -

Operator's Manual SICKLE BAR MOWERS

PGF Operator’s Manual SICKLE BAR MOWERS SKM272, SKM284, SKM296 The operator’s manual is a technical service guide and must always accompany the machine. Manual 970-394B August 2015 SAFETY Take note! This safety alert symbol found throughout this manual is used to call your attention to instructions involving your personal safety and the safety of others. Failure to follow these instructions can result in injury or death. This symbol means: ATTENTION! BECOME ALERT! YOUR SAFETY IS INVOLVED! Signal Words Note the use of the signal words DANGER, WARNING and CAUTION with the safety messages. The appropriate signal words for each have been selected using the following guidelines: DANGER: Indicates an imminently hazardous situation that, if not avoided, will result in death or serious injury. WARNING: Indicates a potentially hazardous situation that, if not avoided, could result in death or serious injury, and includes hazards that are exposed when guards are removed. It may also be used to alert against unsafe practices. CAUTION: Indicates a potentially hazardous situation that, if not avoided, may result in minor or moderate injury. INDEX 1 - GENERAL INFORMATION 4 1.01 - General 4 1.02 - Warranty Information 4 1.03 - Model and Serial Number ID 5 2 - SAFETY PRECAUTIONS 6 2.01 - Preparation 6 2.02 - Starting and Stopping 6 2.03 - Messages and Signs 7 3 - OPERATION 10 3.01 - Operational Safety 10 3.02 - Setup 12 3.03 - Assembly Instructions 12 3.04 - Pre-Operational Check 14 3.05 - Attaching to the Tractor 14 3.06 - Start Up 16 3.07 - Working -

War Collectivism in World War I

WAR COLLECTIVISM Power, Business, and the Intellectual Class in World War I WAR COLLECTIVISM Power, Business, and the Intellectual Class in World War I Murray N. Rothbard MISES INSTITUTE AUBURN, ALABAMA Cover photo copyright © Imperial War Museum. Photograph by Nicholls Horace of “Munition workers in a shell warehouse at National Shell Filling Factory No.6, Chilwell, Nottinghamshire in 1917.” Copyright © 2012 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is gladly granted, provided full credit is given. Ludwig von Mises Institute 518 West Magnolia Avenue Auburn, Alabama 36832 mises.org ISBN: 978-1-61016-250-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. War Collectivism in World War I . .7 II. World War I as Fulfillment: Power and the Intellectuals. .53 Introduction . .53 Piestism and Prohibition . .57 Women at War and at the Polls . .66 Savings Our Boys from Alcohol and Vice . .74 The New Republic Collectivists. .83 Economics in Service of the State: The Empiricism of Richard T. Ely. .94 Economics in Service of the State: Government and Statistics . .104 Index . .127 5 I War Collectivism in World War I ore than any other single period, World War I was the Mcritical watershed for the American business system. It was a “war collectivism,” a totally planned economy run largely by big-business interests through the instrumentality of the cen- tral government, which served as the model, the precedent, and the inspiration for state corporate capitalism for the remainder of the twentieth century. That inspiration and precedent emerged not only in the United States, but also in the war economies of the major com- batants of World War I. -

May/June 2019

Today’s Fern May/June 2019 Publication of the 100 Ladies of Deering, a philanthropic circle of the Deering Estate Foundation The 100 Ladies Again Undertake a Whirlwind Month Like the citizens of Sitges, Spain, the 100 Ladies of Deering are devoted to the preservation of a historic landmark once owned by Charles Deering. Our efforts to conserve and preserve this magniBicent estate located in our backyard, unites us with citizens of Sitges on the other side of the Atlantic. Those who went on our fundraising cruise in April experienced the small town of Sitges’ gratitude to the memory of the Town’s Adopted Son, Charles Deering. One hundred and ten years from the time Deering Birst visited Sitges, we were welcomed like long lost family with choral songs, champagne, and stories of the beloved adopted son’s vision, philanthropy and economic contributions. The stories we share are similar, like here in Cutler, Deering built an “architectural gem” in Sitges and Billed it at the time President Maria and husband David toast a very successful fundraiser with art by renowned artists. The town’s warm cruise to Spain…with side trips to Sitges and Tamarit. welcome given to us was inspiring because it demonstrates their deep “If we love, and we do, appreciation for Charles Deering’s vision and legacy which we both strive to what Charles Deering preserve. I highly encourage you to participate in any future trips where we seek to bequeathed us…If we further understand Charles Deering’s legacy, whether here in Miami, Chicago or consider it to be so Spain. -

Improved Innovative Siddhant Windrower Automated Reaper (IISWAR) B.S Dangi 1, S

12603 B.S Dangi et al./ Elixir Mech. Engg. 54 (2013) 12603-12605 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Mechanical Engineering Elixir Mech. Engg. 54 (2013) 12603-12605 Improved Innovative Siddhant Windrower Automated Reaper (IISWAR) B.S Dangi 1, S. Sen Sharma 2, RK Bharilya 2 and A.K. Prasad 2 1Windrower Reaper, NIF, (National Innovation Foundation), Ahmedabad, India. 2Central Mechanical Engineering Research Institute, Durgapur 713 209, (CSIR, Govt. of India) ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The paper reflects, machine designed and developed by authors that suit medium sized Received: 26 November 2012; farmer and farm industrialist holding only few acres of land. It has been designed and Received in revised form: developed by CMERI, Durgapur, India, in collaboration with NIF(National Innovation 15 January 2013; Foundation, Ahmedabad, India). A number of crops i.e., wheat, and pulse like soybean, Accepted: 18 January 2013; gram have been successfully reaped(harvested), and, concurrently the m/c is ready to undergo reliability&feasibility trial/inspection/check, desired for an Agri Machinery. It will Keywords be indigenously get checked for Nation wide R&D standard. The system is designed by Chaff, inculcating years of expertise in this stream. There is a keen observation by designer to Ear Heads, simplify assembling/disassembly and maintenance/ operations/ of picker reel, cutter link & Straw, blade, roll & push type auger and simplest possible bevel PTO. This prototype is a foolproof Maneuverability, machine, designed with consideration of global knowhow of scientific mechanisms of this Ergonomics. stream. The basic research work has been done thoroughly by selecting adequate technology and scientific calculations in all the assemblies and critical parts e.g.