Automated Vehicles: Analysis of Responses to the Preliminary Consultation Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Led by Organisations Including ABP, Dunbia, Tulip, Dawn Meats, WM Perry

Abattoir, Red Meat Slaughter And Primary Processing – Led by organisations including ABP, Dunbia, Tulip, Dawn Meats, W M Perry Ltd, C H Rowley Ltd, Peter Coates (Alrewas) Ltd, JA Jewett (Meat) Ltd, BW & JD Glaves & Sons Ltd, Euro Quality Lambs Ltd, A Wright & Son, Fowler Bros Ltd, C Brumpton Ltd Accountancy – Led by organisations including Baker Tilly, BDO, Costain, Dains, Deloitte, Government Finance Profession , Ernst & Young, Flemmings, Grant Thornton, Hall and Woodhouse, Harvey & Son, Hazlewoods LLP, Health Education East of England, Kingston Smith, KPMG, Lentells Chartered Accountants, London Borough of Barking and Dagenham, NHS Employers, PwC, Solid State Solutions and Warrington and Halton Hospital NHS Foundation Trust with the Association of Accounting Technicians (AAT), Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA), Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) and the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW). Accountancy (Phase 4) – Led by organisations including Derby Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Selby Jones Ltd, Shapcotts, Skills for Health Academy (North West), Bibby Ship Management, Jackson Stephen LLP, HFMA, Civil Service, Spofforths LLP, Norse Commercial Services Ltd, Norbert Dentressangle, Charles Wells Limited, TaxAssist Accountants, Mazars, Armstrong Watson, MHA Bloomer Heaven. Actuarial – Led by organisations including Aon Hewitt, Barnett Waddingham, Grant Thornton, KPMG, Mercer, Munich Re, PwC and RSA with the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries. Adult Care – Led by organisations including Barchester Healthcare, Caretech Community Services, Creative Support, Hand in Hands, Hendra Health Care (Ludlow), Hertfordshire County Council, Housing and Care 21, Oxfordshire County Council, Progressive Care, Surrey County Council, West England Centre for Inclusive Living, Woodford Homecare. -

IPG Spring 2020 Auto & Motorcycle Titles

Auto & Motorcycle Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} The Brown Bullet Rajo Jack's Drive to Integrate Auto Racing Bill Poehler Summary The powers-that-be in auto racing in the 1920s, namely the American Automobile Association’s Contest Board, prohibited everyone who wasn’t a white male from the sport. Dewey Gaston, a black man who went by the name Rajo Jack, broke into the epicenter of racing in California, refusing to let the pervasive racism of his day stop him from competing against entire fields of white drivers. In The Brown Bullet, Bill Poehler uncovers the life of a long-forgotten trailblazer and the great lengths he took to even get on the track, and in the end, tells how Rajo Jack proved to a generation that a black man could compete with some of the greatest white drivers of his era, wining some of the biggest races of the day. Lawrence Hill Books 9781641602297 Pub Date: 5/5/20 Contributor Bio $28.99 USD Bill Poehler is an award-winning investigative journalist based in the northwest, where he has worked as a Discount Code: LON Hardcover reporter for the Statesman Journal for 21 years. His work has appeared in the Oregonian, the Eugene Register-Guard and the Corvallis Gazette-Times ; online at OPB.org and KGW.com; and in magazines including 240 Pages Carton Qty: 0 Slant Six News , Racing Wheels , National Speed Sport News and Dirt Track Digest . He lives in Salem, Oregon. Biography & Autobiography / Cultural Heritage BIO002010 9 in H | 6 in W How to be Formula One Champion Richard Porter Summary Are you the next Lewis Hamilton? How to be F1 Champion provides you with the complete guide to hitting the big time in top-flight motorsport, with advice on the correct look, through to more advanced skills such as remembering to insert 'for sure' at the start of every sentence, and tips on mastering the accents most frequently heard at press conferences. -

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Procurement

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Procurement Transparency Payments August 2018 Supplier Value Paid 365 HEALTHCARE 1,638.00 365 SECURE CARE LTD 3,775.00 3M UNITEK UK (ORTHODONTIC PRODUCTS) 2,308.19 4M FLOORS UK LIMITED 2,636.76 7 HILLS LEISURE TRUST 5,199.33 A ALGEO LTD 851.60 A BARKER 11,450.00 A CUMBERLIDGE LTD 521.52 A DOWNES 4.50 A FORRESTER 1,974.10 A FRANCIS 70.00 A GRAFTON 2,085.75 A M SAFETY SERVICES 212.16 A M TIME SERVICES 505.02 A MARSHALL 657.40 A MAZAI 8,655.75 A METHLEY 300.00 A P MACKIE 298.40 A R M ANDRZEJOWSKI 347.00 A RIDSDALE 9,801.42 A S CATERING SUPPLIES LTD 179.88 A WATT 300.00 A WILSON 719.46 A WONG 140.00 A WORTH 50.00 A WRIGHT 3,670.96 A&F SPRINKLERS LTD 444.60 A. GAGE OPTICIANS LTD 39.10 A2B OFFICE TECHNOLOGY 38.72 A2I TRASCRIPTION SERVICES 216.00 AAH PHARMACEUTICALS LTD 1,149,702.15 AAL LTD 60.00 ABATRON LTD 692.36 ABBOTT LABORATORIES LTD 718.31 ABBOTT MEDICAL UK LTD 62,489.28 ABBOTT VASCULAR 53,678.40 ABBVIE LTD 37,726.32 ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY AGENCY LIMITED 41,228.41 ACCORD FLOORING LTD 14,540.03 ACE JANITORIAL SUPPLIES LIMITED 2,010.80 ACES 403.20 ACORN ANALYTICAL SERVICES 96.00 ACORN INDUSTRIAL SERVICES LTD 3,837.93 ACROSTAK 1,401.60 ACTION ON HEARING LOSS 497.52 ACTIVE DOCUMENTS LTD 2,094.60 Page 1 of 39 Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Procurement Transparency Payments August 2018 Supplier Value Paid ACUMED LTD 12,312.11 ADEC DENTAL UK LTD 2,778.84 ADECCO UK LTD 36,310.63 ADEPT LOCUMS LTD 49,122.60 ADI ENVIRONMENTAL LTD 4,506.00 ADMIRAL DENTAL LABORATORY LTD 2,047.19 ADUR -

O/S 310, Luton Road

Full Property Address Property Reference Number Primary Liable party name Current Rateable Value (3208/0061) O/S 310, Luton Road, Chatham, Kent, ME4 5BX 0445031001N Clear Channel Uk Ltd 600 Arqiva Roof Top (Shared 166074), Strood Ate, St Mary'S Road, Strood, Rochester, Kent, ME2 4DF 2635000070 Arqiva Ltd 41750 Pt 1st Flr, Medway Arts Centre, The Brook, Dock Road, Chatham, Kent, ME4 4SE 0254080310N Medway Council - Culture And Community Finance Team 4900 (3208/0058) O/S 92, Chatham Hill, Chatham, Kent, ME5 7AL 0211009420N Clear Channel Uk Ltd 600 (3208/0059) Adj Upper Luton Road/, Luton Road, Chatham, Kent, ME4 5AA 0444081210N Clear Channel Uk Ltd 600 (3208/0060) Opp York Hill, Luton Road, Chatham, Kent, ME4 5AA 0445081010N Clear Channel Uk Ltd 600 (3208/0062) O/S Crest Hotel, Maidstone Road, Chatham, Kent, ME5 9SE 0450083301N Clear Channel Uk Ltd 600 (3208/0064) O/S, 304, City Way, Rochester, Kent, ME1 2BL 1240030420N Clear Channel Uk Ltd 600 (3208/0067) O/S 120, Bligh Way, Strood, Rochester, Kent, ME2 2XG 2157000121N Clear Channel Uk Ltd 300 (3208/0068) Opp Whitegates Service Station, Gravesend Road, Strood, Rochester, Kent, ME2 3PW 2393011811N Clear Channel Uk Ltd 600 (3208/0069) Opp, 3, High Street, Strood, Rochester, Kent, ME2 4AB 2419000020N Clear Channel Uk Ltd 600 (3208/0072) O/S Post Office, North Street, Strood, Rochester, Kent, ME2 4SX 2546001520N Clear Channel Uk Ltd 300 (3208/0073) Opp St Marys Road, North Street, Strood, Rochester, Kent, ME2 4SN 2546001620N Clear Channel Uk Ltd 300 (3208/0074) O/S, 118, Watling Street, Strood, -

Fleet News April 23, 2020 Fleetnewsapril 23 2020 £6.00 ■ ADVICE on MANAGING YOUR FLEET THROUGH COVID-19 YOUR on MANAGING ADVICE

April 23 2020 £6.00 [email protected] Contact the Fleet Fit team Fit team Fleet Contact the at News Fleet shi�s in performance, efficiency and endurance. their Fleet Fitness. Many little changes can add up to big to can add up little changes Fitness. Many Fleet their fleets. to more attention can benefit from paying size fleet Any more agile Leaner Fitter, Fitter, FleetNews April 23, 2020 ■ ADVICE ON MANAGING YOUR FLEET THROUGH COVID-19 ■ NISSAN AUTONOMOUS VEHICLE PROJECT SHOWS POTENTIAL ■ LAUNCH OF FLEET & MOBILITY LIVE ■ HOW AUTO WINDSCREENS SAVED MORE THAN £150K ■ EX-DRAGON WANTS DRIVE SOFTWARE TO BE ‘GLOBAL LEADER’ INSIDE FRONT PANEL Start finding FleetFleetNewsNewAprils 23 2020 £6.00 the marginal CommercialINCORPORATING Fleet gains Fleet spotlight: Auto Windscreens ‘My best If you have immediate fleet performance targets career move’ to tackle or you are looking for ways to become Just 30 months in, Shaun Atton more agile and ready to respond to changes has revolutionised fleet practices in legislation, taxation, fleet finance or new to save more than £150k and win technology. Beginning to pay more attention most improved fleet of the year to your Fleet Fitness is a great way to start developing leaner mobility solutions that are more prepared for the future. Working closely with our Fleet Fit coaches or using the free resources and advice available from our website is a fantastic way to start racking up the marginal gains, the small tweaks to fleet operation that can be compounded to create big shifts in overall performance. The UK’s most influential fleet For any questions on your Fleet Fitness event is back with a new name email: [email protected] and two days of packed content. -

Commercialfleet ■

Fleet News January 21, 2021 FleetNewsJanuary 21 2021 £6.00 n INCORPORATING REAL-WORLD TESTING OF FULLY-AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES OF FULLY-AUTONOMOUS TESTING REAL-WORLD CommercialFleet n PUBLIC CHARGING INFRASTRUCTURE KEY TO EV SUCCESS EV SUCCESS KEY TO INFRASTRUCTURE PUBLIC CHARGING n ALTRAD SERVICES’ RECIPE FOR A SAFER FLEET SERVICES’ RECIPE FOR ALTRAD n CHEVIN CAPITALISES ON ‘THE NEW NORMAL’ ON ‘THE NEW NORMAL’ CHEVIN CAPITALISES Call for n ENTRIESEHOW DROWNING DECISION-MAKERS CAN IN DATA AVOID NTRIES See inside for full details of how to enter the Fleet News Awards 2021 adRocket Plug into the all-new Vauxhall electric and hybrid range ULEZ and congestion charge exempt Reduced or zero % BiK Reduced service maintenance and repair costs 03305 878 222 | [email protected] Contact your local Fleet Sales Manager for more information on our exciting new electric range. Fuel economy and CO2 results for the Vivaro-e range 100kW (136PS). Mpg (l/100km): N/A. CO2 emissions: 0g/km. Electric range up to 205 miles (WLTP). Fuel economy and CO2 results for the Grandland X Hybrid range 165kW – 221kW (225 – 300PS). Combined mpg (l/100km): 192 (1.5) – 204 (1.4). CO2 emissions: 29 – 31g/km. Electric range: up to 35 miles (WLTP). Fuel economy and CO2 results for the Mokka-e range 100kW (136PS). Mpg (l/100km): N/A. CO2 emissions: 0g/km. Electric range up to 201 miles (WLTP).* Fuel economy and CO2 results for the Corsa-e range 100kW (136PS). Mpg (l/100km): N/A. CO2 emissions: 0g/km. Electric range up to 209 miles (WLTP). -

BVRLA Annual Review 2018

About the BVRLA Established in 1967, the British Vehicle Rental & Leasing Association (BVRLA) is the UK trade body for companies engaged in vehicle rental and leasing. BVRLA membership provides a quality assurance benchmark, reassuring customers that the company they are dealing with adheres to the highest standards of professionalism and fairness. The association achieves this by maintaining industry standards and regulatory compliance via its mandatory codes of conduct, inspection programme and conciliation service. To support this work, the BVRLA shares information and promotes best practice through its extensive range of training and events. On behalf of its 950+ members, the BVRLA works with governments, public sector agencies, industry associations and key business influencers across a wide range of road transport, environmental, taxation, technology and finance-related issues. BVRLA members are responsible for a combined fleet of almost five million cars, vans and trucks, supporting around 465,000 jobs and contributing nearly £49bn to the economy each year. 91% of members say that the BVRLA provides status and credibility to their organisation. 2018 Member Survey 2 Committee of Management The Committee of Management is the BVRLA’s board of directors, responsible for strategic direction and policy as well as ensuring that the association is run on a sound financial basis. Matt Dyer Nina Bell Freddie Aldous Chairman Vice Chairman 1928-2017 With more than 20 years’ industry In her role of Managing Director Brian Back BVRLA Honorary Treasurer The BVRLA said goodbye to experience, Matt Dyer, Managing of Avis Budget Group and Zipcar David Hosking Tuskerdirect its Honorary Life President, Director of LeasePlan UK, is Northern Region, covering the UK, Freddie Aldous, who passed responsible for a business with Norway, Sweden and Denmark, Ed Cowell Fraikin away in December 2017. -

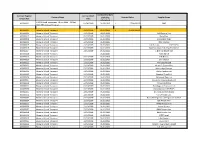

Contract Value Supplier

Contract End Date Contract Register Contract Start Contract Name (including Contract Value Supplier Name Unique Key Date extensions) CT0101 Food - provisions - 01 Jun 2009 - 31 May 100000001 01/06/2009 31/05/2013 £ 2,700,000.00 3663 2012 NHS Scotland Contract 100000011 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 £ 25,000,000.00 100000010 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 09/04/2010 Bolt Private Hire 100000012 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 Ferry Fare 100000013 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 Aerial ABW Cabs 100000014 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 Alba Coaches 100000015 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 Call Us Cabs USE A3733 100000016 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 Coulman Coaches & Chauffeur Drive 100000017 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 E & M Horsburgh Ltd 100000018 Home to School Transport 01/11/2013 Frank White 100000019 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 G & R Taxis 100000020 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 John W Jack 100000021 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 AAA Coaches Ltd 100000022 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 M and D Private Hire 100000023 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 McKendrys Coaches 100000024 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 Ratho Coaches Ltd 100000025 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 Shandon Travel Ltd 100000026 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 01/11/2013 Edinburgh Taxis Ltd 100000027 Home to School Transport 22/10/2009 -

How Millennials Are Disrupting the World of Business

Environment Economy Society December 2017 FOR ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABILITY PROFESSIONALS www.iema-transform.net How millennials are disrupting the world of business PLUS Survival of the fi ttest Chris D Thomas on nature’s way of coping Green shoots Investments to tackle climate change Brexit across borders Complexities of environmental governance p01_Transform_Dec2017_COVER_v3•CT.indd 1 21/11/2017 15:34 Two new routes to IEMA membership If you’re looking for a route to membership or to upskill your team, our new training courses will provide the knowledge and skills you need to do your job. The Foundation Certificate in Environmental Management gives a first foot in the door of the Environment & Sustainability profession and leads directly to Associate membership of IEMA. The brand new Certificate in Environmental Management is designed to instil, recognise and support environment and sustainability knowledge and is the pathway to Practitioner membership. Learn more and sign up today: www.iema.net/training/new-courses-2017 p02.IEMA.Dec17.indd 24 17/11/2017 10:53 Contents DECEMBER 24 Upfront 04 Comment Tim Balcon, CEO of IEMA, on how members have inspired what has been a year to remember 05 Industry news roundup 07 COP23 news 08 IEMA news Annual members survey results; IEMA attends Bonn climate talks; More members awarded Fellowship Regulars 19 10 Legal brief FEATURES Regulations, consultations and court news, including fi ne for NE region activities 14 Interview: Professor Chris D Thomas Leading ecologist and author argues how 12 In focus -

Fleet Manager of the Year Stew Art Lightbody Fca

FleetNews december 12, 2019 n Fleet manager oF the year Stewart lightbody n Fca Fleet director andy waite n volkSwagen golF FirSt drive n mobility/ev SolutionS For FleetS n hyundai’S zero emiSSion Future n new volvo truckS md robert grozdanovSki FleetNewsDecember 12 2019 £6.00 CommercialINCORPORATING Fleet Spotlight: FCA Group Andy Waite gets excited about his 2020 launch plans Mobility/EV solutions Top fleets debate the merits of EVs and mobility New Volkswagen Golf Fleet’s most popular car – now even better WINNER Stewart Lightbody, M Group Services ‘Ask questions; be inquisitive’ Fleet manager of the year Stewart Lightbody reflects on his first six months in charge of the M Group Services fleet and his plans for 2020 adRocket CONTENTS NEWS AND OPINION 4 Biggest fleet concerns for 2020 9 ‘Make or break’ year for diesel 10 FORS plans two major changes 13 Fleets urged: act now on emissions 14 Ian Hill enters the Hall of Fame 15 The past month’s news headlines 16 Have your say: readers’ letters MEASURE DISTANCE IN EMOTIONS. 82 Last word with Mark Dickens NOT MILES. TOMORROW’S FLEET: MOBILITY 20 Mobility and electric solutions ‘Fighting in the car park’ 24 EV charging Active buildings can benefit EVs 26 Hyundai’s zero emission vision 16 electric vehicles by 2025 28 Guest opinion: Daniel Ruiz CAVs and expensive tech dilemma WHAT IT TAKES TO TODAY’S FLEET: BECOME FLEET DECISION-MAKING IN THE MANAGER OF THE 38 Fleet skills with ICFM SPOTLIGHT YEAR 2020 is time for change 30 Stewart Lightbody P30 Fleet manager of the year advises: ‘Ask questions; -

Eeht Rf .Lanigio Tsusons Bs R Ettti U

The No.1 magazine for automotive information www.aftermarketonline.net OCTOBER 2018 facebook.com/ngksparkplugsuk NGK UK YouTube ngkntk.com There’s no substitute for anoriginal. S P A R K P L U G S : G L O W P L U G S : S E N S O R S : I G N I T I O N C O I L S F R O M T H E W O R L D ’ S N O . 1 Rights and wrongs Frank Massey: Let’s Automechanika of fault codes P20 get it started P22 Frankfurt P31 John Batten looks at how you How to get to grips with ignition All the thrills, spills, and should be dealing with fault combustion diagnostics. unveilings from the biggest codes and gives his Top 7 Tips for Identifying what is causing the aftermarket show in the world. INSIDE Fault Code Success. problem can be tricky. All this and much more! TOP TECHNICIAN 2019 LAUNCHES! TURN TO PAGE 26 FOR ALL THE DETAILS sachsprovenperformance.FRuk THE FASTEST TOURING CARS GO 0-60MPH IN2.6 SECONDS with A SACHS CLUTCH Official Partner of BMW Motorsport PROVEN PERFORMANCE CONTENTS BUSINESS 08 Big issue: Head for the Brexit AUTOMECHANIKA 12 Adam Bernstein: Succeeding with succession 14 Neil Pattemore: Managing a winning team FOR THE PEOPLE 16 Andy Savva: Customer care TECHNICAL t’s been a busy few weeks here at Aftermarket. Apart from the entire mag team decamping to Germany for Automechanika 18 Hannah Gordon: In the heat of the fault Frankfurt 2018, which you can read about on pages 31-37, we 19 Barry Babister: Site Audit snippets have been working to get Top Technician and Top Garage ready for 20 John Batten: Rights and wrongs of fault codes I2019. -

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Procurement Transparency Payments June-2019

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust 04-JUL-2019 12:29:58 Procurement Transparency Payments June-2019 Supplier Value Paid 1ST CALL MOBILITY LTD 1,650.00 365 SECURE CARE LTD 19,500.00 3M UNITED KINGDOM PLC 540.00 3M UNITEK UK (ORTHODONTIC PRODUCTS) 833.74 A AVERY 317.55 A BOON 120.00 A CASTANON 120.00 A CROPPER 300.95 A CUMBERLIDGE LTD 13,979.58 A FORRESTER 2,942.80 A GRAFTON 872.52 A HART 32.00 A KOULAOUZIDIS 147.80 A L CLINICIAN LIMITED (RAJAK) 4,754.00 A LITTLEWOOD 13.60 A M TIME SERVICES 572.22 A MARSHALL 598.40 A MAZAI 10,391.67 A MOHAMMED 74.50 A MURINO 117.74 A R M ANDRZEJOWSKI 364.00 A RIDSDALE 7,632.06 A SAGUAR 245.00 A SLATER 327.81 A SOMERVILLE LTD 438.70 A W BENT LTD 81.17 A-Z TEC MEDICAL LIMITED 508.80 A. GAGE OPTICIANS LTD 118.60 AAH PHARMACEUTICALS LTD 878,437.64 ABATRON LTD 198.45 ABBOTT LABORATORIES LTD 315.34 ABBOTT MEDICAL UK LTD 165,057.40 ABBVIE LTD 3,154.42 AC COSSOR & SON (SURGICAL) LTD 118.39 AC MAINTENANCE LTD 878.40 ACA ANNUAL CONFERENCE & EXHIBITION 2019 130.00 ACCORD FLOORING LTD 7,738.65 ACE JANITORIAL SUPPLIES LIMITED 8,348.67 ACORN ANALYTICAL SERVICES 19.20 ACORN INDUSTRIAL SERVICES LTD 3,203.29 ACTACCOM LIMITED 503,028.84 ACTELION PHARM UK LTD 11,280.00 ACTION HANDLING EQUIPMENT LTD 186.30 ACTIVE DOCUMENTS LTD 2,094.00 ACTIVE TAGGING LTD 7,799.90 Page 1 of 34 Supplier Value Paid ACUMED LTD 862.68 ADAM ROUILLY LTD 1,262.40 ADEC DENTAL UK LTD 2,737.29 ADECCO UK LTD 20,049.71 ADELPHI HEALTHCARE PACKAGING 928.80 ADI ENVIRONMENTAL LTD 1,404.00 ADMIRAL DENTAL LABORATORY LTD 3,625.94 ADMOR LTD 403.68