The Snow Leopard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi

by Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi Preface About the Author In the whole world, there are more than 30,000 species Keshav Ravi is a caring and compassionate third grader threatened with extinction today. One prominent way to who has been fascinated by nature throughout his raise awareness as to the plight of these animals is, of childhood. Keshav is a prolific reader and writer of course, education. nonfiction and is always eager to share what he has learned with others. I have always been interested in wildlife, from extinct dinosaurs to the lemurs of Madagascar. At my ninth Outside of his family, Keshav is thrilled to have birthday, one personal writing project I had going was on the support of invested animal advocates, such as endangered wildlife, and I had chosen to focus on India, Carole Hyde and Leonor Delgado, at the Palo Alto the country where I had spent a few summers, away from Humane Society. my home in California. Keshav also wishes to thank Ernest P. Walker’s Just as I began to explore the International Union for encyclopedia (Walker et al. 1975) Mammals of the World Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List species for for inspiration and the many Indian wildlife scientists India, I realized quickly that the severity of threat to a and photographers whose efforts have made this variety of species was immense. It was humbling to then work possible. realize that I would have to narrow my focus further down to a subset of species—and that brought me to this book on the Endangered Mammals of India. -

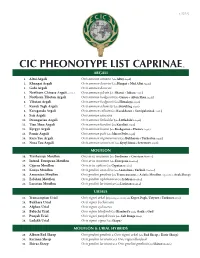

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve

Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve April 6, 2021 About Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve was the first biosphere reserve in India established in the year 1986. It is located in the Western Ghats and includes 2 of the 10 biogeographical provinces of India. The total area of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve is 5,520 sq. km. It is located in the Western Ghats between 76°- 77°15‘E and 11°15‘ – 12°15‘N. The annual rainfall of the reserve ranges from 500 mm to 7000 mm with temperature ranging from 0°C during winter to 41°C during summer. The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve encompasses parts of Tamilnadu, Kerala and Karnataka. The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve falls under the biogeographic region of the Malabar rain forest. The Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary Bandipur National Park, Nagarhole National Park, Mukurthi National Park and Silent Valley are the protected areas present within this reserve. Vegetational Types of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve Nature of S.No Forest type Area of occurrence Vegetation Dense, moist and In the narrow Moist multi storeyed 1 valleys of Silent evergreen forest with Valley gigantic trees Nilambur and Palghat 2 Semi evergreen Moist, deciduous division North east part of 3 Thorn Dense the Nilgiri district Savannah Trees scattered Mudumalai and 4 woodland amid woodland Bandipur South and western High elevated Sholas & catchment area, 5 evergreen with grasslands Mukurthi national grasslands park Flora About 3,300 species of flowering plants can be seen out of species 132 are endemic to the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. The genus Baeolepis is exclusively endemic to the Nilgiris. -

English Cop18 Prop. 1 CONVENTION on INTERNATIONAL

Original language: English CoP18 Prop. 1 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Colombo (Sri Lanka), 23 May – 3 June 2019 CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal Tajikistan proposes the transfer of its population of Heptner's or Bukhara markhor, Capra falconeri heptneri, from Appendix I to Appendix II in accordance with a precautionary measure specified in Annex 4 of Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP16). Specification of the criteria in Annex 2, Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP16) that are satisfied Criterion B of Annex 2a applies, namely “It is known, or can be inferred or projected, that regulation of trade in the species is required to ensure that the harvest of specimens from the wild is not reducing the wild population to a level at which its survival might be threatened by continued harvesting or other influences”. The applicability of this criterion is further substantiated in Section C below. Furthermore, criteria A and B of Annex 2b apply, namely: 1. “The specimens of the species in the form in which they are traded resemble specimens of a species included in Appendix II so that enforcement officers who encounter specimens of CITES-listed species are unlikely to be able to distinguish between them”; and 2. “There are compelling reasons other than those given in criterion A above to ensure that effective control of trade in currently listed species is achieved.” As further detailed in Section C, point 9 below, there may be difficulty in distinguishing between products of Heptner's markhor (e.g. -

Forest and Wildlife F I L D L I

2 e Forest and Wildlife f i l d l i 2.1 Introduction Forest plays a vital role in safeguarding the W d amil Nadu is the southern most state of India. The environment and contributes much to economic n a t total geographical area of Tamil Nadu is 1,30,058 development. Forests are generally considered s e r sq.kms, of which the recorded forest area is environmental capital in that it directly relates to the o T F 22,877 sq.kms, which constitute 17.59% of the States environment. Conservation and preservation of forest is a geographical area2. The forest area of the State is classified as pre-requisite for maintaining a healthy eco-system. Besides Reserved Forest, Reserved land and Unclassified forest. ensuring ecological stability, forest provides employment Reserved Forests (RF) covers about 19,388 sq.km (85%), opportunities to rural and tribal folk and provides wood and Protected Forests (PF) covers about 2,183 sq.km (9.6%) and minor forest products like honey, herbs, fruits, berries and Unclassified Forest (UF) covers an area of about 1,306 sq.km materials for domestic use.3 (5.8%)3 2.2 Forest area Physiographically the salient features of the land are the coastal plains along the east coast with a land coverage of The State of Forest Report 2003, of Forest Survey of 17,150 sq.kms (approx) and Western Ghats, a continuous India shows the recorded forest area of the state as mass of composite hill ranges of high elevation along the 22,877 sq.km in extent which is 17.59% of the geographical west, extending to an area of 44,401 sq.kms (approx). -

Federal Register/Vol. 79, No. 194

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 194 / Tuesday, October 7, 2014 / Rules and Regulations 60365 applicant in preparation of a program of FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Suleiman markhor (Capra falconeri projects. This work may involve joint Janine Van Norman, Chief, Branch of jerdoni), and the Kabul markhor (C. f. site inspections to view damage and Foreign Species, Ecological Services megaceros), as well as 157 other U.S. reach tentative agreement on the type of Program, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; and foreign vertebrates and permanent repairs the applicant will telephone 703–358–2171; facsimile invertebrates, as endangered under the undertake. Project information should 703–358–1735. If you use a Act (41 FR 24062). All species were be kept to a minimum, but should be telecommunications device for the deaf found to have declining numbers due to sufficient to identify the approved (TDD), please call the Federal the present or threatened destruction, disaster or catastrophe and to permit a Information Relay Service (FIRS) at modification, or curtailment of their determination of the eligibility of 800–877–8339. habitats or ranges; overutilization for proposed work. If the appropriate FTA SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: commercial, sporting, scientific, or Regional Administrator determines the educational purposes; the inadequacy of damage assessment report is of Executive Summary existing regulatory mechanisms; or sufficient detail to meet these criteria, I. Purpose of the Regulatory Action some combination of the three. additional project information need not However, the main concerns were the We are combining two subspecies of be submitted. high commercial importance and the (g) The appropriate FTA Regional markhor currently listed under the inadequacy of existing regulatory Administrator’s approval of the grant Endangered Species Act of 1973, as mechanisms to control international application constitutes a finding of amended (Act), the straight-horned trade. -

Ecology and Conservation of Mountain Ungulates in Great Himalayan National Park, Western Himalaya

FREEP-GHNP 03/10 Ecology and Conservation of Mountain Ungulates in Great Himalayan National Park, Western Himalaya Vinod T. R. and S. Sathyakumar Wildlife Institute of India, Post Box No. 18, Chandrabani, Dehra Dun – 248 001, U.P., INDIA December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are thankful to Shri. S.K. Mukherjee, Director, Wildlife Institute of India, for his support and encouragement and Shri. B.M.S. Rathore, Principal Investigator of FREEP-GHNP Project, for valuable advice and help. We acknowledge the World Bank, without whose financial support this study would have been difficult. We are grateful to Dr. Rawat, G.S. for his guidance and for making several visits to the study site. We take this opportunity to thank the former Principal Investigator and present Director of GHNP Shri. Sanjeeva Pandey. He is always been very supportive and came forward with help- ing hands whenever need arised. Our sincere thanks are due to all the Faculty members, especially Drs. A.J.T. Johnsingh, P.K. Mathur, V.B. Mathur, B.C. Choudhary, S.P. Goyal, Y.V. Jhala, D.V.S. Katti, Anil Bharadwaj, R. Chundawat, K. Sankar, Qamar Qureshi, for their sug- gestions, advice and help at various stages of this study. We are extremely thankful to Shri. S.K. Pandey, PCCF, HP, Shri. C.D. Katoch, former Chief Wildlife Warden, Himachal Pradesh and Shri. Nagesh Kumar, former Director GHNP, for grant- ing permission to work and for providing support and co-operation through out the study. We have been benefited much from discussions with Dr. A.J. Gaston, Dr. -

Ungulate Tag Marketing Profiles

AZA Ungulates Marketing Update 2016 AZA Midyear Meeting, Omaha NE RoxAnna Breitigan -The Living Desert Michelle Hatwood - Audubon Species Survival Center Brent Huffman -Toronto Zoo Many hooves, one herd COMMUNICATION Come to TAG meetings! BUT it's not enough just to come to the meetings Consider participating! AZAUngulates.org Presentations from 2014-present Details on upcoming events Husbandry manuals Mixed-species survey results Species profiles AZAUngulates.org Content needed! TAG pages Update meetings/workshops Other resources? [email protected] AZAUngulates.org DOUBLE last year’s visits! Join our AZA Listserv [AZAUngulates] Joint Ungulate TAG Listserv [email protected] To manage your subscription: http://lists.aza.org/cgi-bin/mailman/listinfo/azaungulates Thanks to Adam Felts (Columbus Zoo) for moderating! Find us on Facebook www.facebook.com/AZAUngulates/ 1,402 followers! Thanks to Matt Ardaiolo (Denver Zoo) for coordinating! Joining forces with IHAA International Hoofstock Awareness Association internationalhoofstock.org facebook.com INITIATIVES AZA SAFE (Saving Animals From Extinction) AZA initiative Launched in 2015 Out of 144 nominations received, 24 (17%) came from the Ungulate TAGs (all six TAGs had species nominated). Thank you to everyone who helped!!! Marketing Profiles •Audience: decision makers •Focus institutional interest •Stop declining trend in captive ungulate populations •63 species profiles now available online Marketing Profiles NEW for this year! Antelope & Giraffe TAG Caprinae TAG Black -

Status and Ecology of the Nilgiri Tahr in the Mukurthi National Park, South India

Status and Ecology of the Nilgiri Tahr in the Mukurthi National Park, South India by Stephen Sumithran Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fisheries and Wildlife Sciences APPROVED James D. Fraser, Chairman Robert H. Giles, Jr. Patrick F. Scanlon Dean F. Stauffer Randolph H. Wynne Brian R. Murphy, Department Head July 1997 Blacksburg, Virginia Status and Ecology of the Nilgiri Tahr in the Mukurthi National Park, South India by Stephen Sumithran James D. Fraser, Chairman Fisheries and Wildlife Sciences (ABSTRACT) The Nilgiri tahr (Hemitragus hylocrius) is an endangered mountain ungulate endemic to the Western Ghats in South India. I studied the status and ecology of the Nilgiri tahr in the Mukurthi National Park, from January 1993 to December 1995. To determine the status of this tahr population, I conducted foot surveys, total counts, and a three-day census and estimated that this population contained about 150 tahr. Tahr were more numerous in the north sector than the south sector of the park. Age-specific mortality rates in this population were higher than in other tahr populations. I conducted deterministic computer simulations to determine the persistence of this population. I estimated that under current conditions, this population will persist for 22 years. When the adult mortality was reduced from 0.40 to 0.17, the modeled population persisted for more than 200 years. Tahr used grasslands that were close to cliffs (p <0.0001), far from roads (p <0.0001), far from shola forests (p <0.01), and far from commercial forestry plantations (p <0.001). -

The Snow Leopard Which Was Somcwhtre a Thousand Feet Above Near a Goat It Had Killed the Previous Dav

Some memb ere of the subfamily Caprinae chamois Himalayan tahr Alpine ibex Kashmir markhor aoudad saiga ' :w1 (Some taxonomis~rplace cl~iru saiga with the antelopes. Spanish goat and DRAWINGS BY RICHARD KEANE not with the sheep and goats and their allies.) STONES OF SILENCE Illustrated with sketches by Jean Pruchnilr and photographs by George B. Schaller The Viking Press New York Contents Acknowledgments v List of Illustrations ix Path to the Mountains I The Snow Lcoyard 8 Beyond the Ranges 5 I Karakoram 74 Mountains in the Desert I I 5 Cloud Goats I 50 Kang Chu 174 Journey to Crystal Mountain 203 Appendix 279 Index 283 The Snow ~eo-pard hen the snow clouds retreated, the gray slopes ancl jagged cliffs Ivere gone, as were the livestock trails and raw stumps of felled oak. Several inches of fresh snow softened all contours. Hunched against December's cold, I scanned the slope, looking for the snow leopard which was somcwhtre a thousand Feet above near a goat it had killed the previous dav. Rut onlv cold proulled thc slopes. Slowly I climbed upward, kicking \reps into the snow and angling toward a 5pur of rock from ~vhichto Yurvey the vallcv. Soon scree gave way to a chaos of boulders and rocky outcrops, the slopes motionless and ~ilentac if devoid of life. Then I saw the snow leoparcl, a hundred ancl fifty feet away, peer- ing at me from the spur, her bodv so \vcll moltled into the contours THE SNOW LEOPARD ' 9 of the boulders that she seemed a part of them. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

The Nilgiri Tahr in the Western Ghats, India

IND 2015 STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE NILGIRI TAHR IN THE WESTERN GHATS, INDIA Status and Distribution of the Nilgiri Tahr in the Western Ghats, India | P 1 Authors Paul Peter Predit, Varun Prasath, Mohanraj, Ajay Desai, James Zacharia, A. J. T. Johnsingh, Dipankar Ghose, Partha Sarathi Ghose, Rishi Kumar Sharma Suggested citation Predit P. P., Prasath V., Raj M., Desai A., Zacharia J., Johnsingh A. J. T., Ghose D., Ghose P. S., Sharma R. K. (2015). Status and distribution of the Nilgiri Tahr Nilgiritragus hylocrius, in the Western Ghats, India. Technical report, WWF-India. This project was funded by Nokia. Photos by Paul Peter Predit Design by Chhavi Jain / WWF-India Published by WWF-India Copyright © 2015 All rights reserved Any reproduction in full or part of this publication must mention the title and credit the mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. WWF-India 172-B, Lodi Estate, New Delhi 110 003 Tel: +91 11 4150 4814 www.wwfindia.org STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE NILGIRI TAHR IN THE WESTERN GHATS, INDIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Researchers: We thank field biologists B. Navaneethan, Suresh, Soffia, Immanuel Victor Prince and M.Ravikanth for participating in the field surveys at various stages. They were ably assisted and gained from the knowledge and skills of field assistants R.Veluswamy and Siddarth. We are grateful to the Forest Departments of Tamil Nadu and Kerala who readily granted us permission for carrying out this study in their respective states. We wish to thank Dr. K.P. Ouseph, PCCF and Chief Wildlife Warden Kerala and Thiru. R. Sundararaju, PCCF and Chief Wildlife Warden of Tamil Nadu for permits and support to this project.