Canada and China at 40

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Aboriginal Justice Inquiry-Child Welfare Initiative in Manitoba

The Aboriginal Justice Inquiry-Child Welfare Initiative in Manitoba: A study of the process and outcomes for Indigenous families and communities from a front line perspective by Gwendolyn M Gosek MSW, University of Manitoba, 2002 BA, University of Manitoba, 2002 BSW, University of Manitoba, 1991 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School of Social Work © Gwendolyn M Gosek, 2017 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee The Aboriginal Justice Inquiry-Child Welfare Initiative in Manitoba: A study of the process and outcomes for Indigenous families and communities from a front line perspective By Gwendolyn M Gosek MSW, University of Manitoba, 2002 BA, University of Manitoba, 2002 BSW, University of Manitoba, 1991 Supervisory Committee Dr. Leslie Brown, School of Social Work Supervisor Dr. Jeannine Carrière, School of Social Work Departmental Member Dr. Susan Strega, School of Social Work Departmental Member Dr. Sandrina de Finney, School of Child and Youth Care Outside Member iii Abstract As the number of Indigenous children and youth in the care of Manitoba child welfare steadily increases, so do the questions and public debates. The loss of children from Indigenous communities due to residential schools and later on, to child welfare, has been occurring for well over a century and Indigenous people have been continuously grieving and protesting this forced removal of their children. In 1999, when the Manitoba government announced their intention to work with Indigenous peoples to expand off-reserve child welfare jurisdiction for First Nations, establish a provincial Métis mandate and restructure the existing child care system through legislative and other changes, Indigenous people across the province celebrated it as an opportunity for meaningful change for families and communities. -

Saskatchewan Elections: a History December 13Th, 1905 the Liberal Party Formed Saskatchewan’S First Elected Government

SaSkatcheWan EleCtIonS: A History DecemBer 13th, 1905 The Liberal Party formed Saskatchewan’s first elected government. The Liberals were led by Walter Scott, an MP representing the area of Saskatchewan in Wilfred Laurier’s federal government. Frederick Haultain, the former premier of the Northwest Territories, led the Provincial Rights Party. Haultain was linked to the Conservative Party and had advocated for Alberta and Saskatchewan to be one province named Buffalo. He begrudged Laurier for creating two provinces, and fought Saskatchewan’s first election by opposing federal interference in provincial areas of jurisdiction. RESultS: Party Leader Candidates elected Popular vote Liberal Walter Scott 25 16 52.25% Provincial Rights Frederick Haultain 24 9 47.47% Independent 1 - 0.28% Total Seats 25 AuguST 14th, 1908 The number of MLAs expanded to 41, reflecting the rapidly growing population. The Liberals ran 40 candidates in 41 constituencies: William Turgeon ran in both Prince Albert City and Duck Lake. He won Duck Lake but lost Prince Albert. At the time it was common for candidates to run in multiple constituencies to help ensure their election. If the candidate won in two or more constituencies, they would resign from all but one. By-elections would then be held to find representatives for the vacated constituencies. This practice is no longer allowed. RESultS: Party Leader Candidates elected Popular vote Liberal Walter Scott 41 27 50.79% Provincial Rights Frederick Haultain 40 14 47.88% Independent-Liberal 1 - 0.67% Independent 2 - 0.66% Total Seats 41 July 11th, 1912 The Provincial Rights Party morphed into the Conservative Party of Saskatchewan, and continued to campaign for expanding provincial jurisdiction. -

Canada's Policy Towards Communist China, 1949-1971

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations from 2009 2014-01-22 Canada's policy towards Communist China, 1949-1971 Holomego, Kyle http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/494 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons CANADA’S POLICY TOWARDS COMMUNIST CHINA, 1949-1971 by Kyle Holomego A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Lakehead University December 2012 1 Abstract The decision of the Canadian government in 1970 to recognize the People’s Republic of China, which controlled Mainland China, as the official government of China, as opposed to the Republic of China, which only controlled Taiwan, was the end result of a process lasting more than two decades. In that time frame, Canada’s China policy would undergo many different shifts. A close examination shows that these shifts were closely linked to the shifting attitudes of successive Canadian leaders. Four different prime ministers would serve in office during Canada’s recognition process, and the inauguration of each prime minister signaled a shift in Canada’s China policy. The issue of recognizing the People’s Republic of China was intertwined with several other issues that were important to Canada. Among these were the economic potential of China, Canada’s need for collective agreements to ensure its security, the desire of the United States to influence Canadian policy, and the desire of Canadian officials to demonstrate the independence of Canadian policy. Of the four prime ministers, three – Louis St. -

The Evolution of Agricultural Support Policy in Canada Douglas D. Hedley

The Evolution of Agricultural Support Policy in Canada CAES Fellows Paper 2015-1 Douglas D. Hedley The Evolution of Agricultural Support Policy in Canada1 by Douglas D. Hedley Agricultural support programs have come under increasing scrutiny over the past two decades as successive attempts in trade negotiations have been made to curtail levels of support and to better identify (and subsequently reduce) those programs yielding the greatest distorting effects on trade. Support programs in Canada have gone through very substantial change over the past 50 years in response to these broad ranging economic, international, and social objectives and pressures. Indeed, the evolution in producer support dates back to the beginnings of the 20th century. In attempting to understand the significant turning points and pressures for change, this paper examines the origins of support policies for Canadian agriculture from the late 1800s to the present time. The paper is written with the understanding that policy changes are path dependent, that is, policies in place at any point in time condition both the nature of policy change in the future as well as the pace and direction of change. The paper is limited to an examination of the support and stabilization policies for Canadian agriculture. One closely related issue is the emergence of marketing arrangements within Canada, some of which involve support for prices or incomes for farmers. As well, the historic role of cooperatives, initially in the western Canada grains industry and subsequently in the Canadian dairy industry, has overtones of price stability and support in some cases. However, while these topics are noted throughout the paper where they specifically involve stability or support or relate to the determination of federal and provincial powers, their history is not detailed in this paper. -

Backgrounder

UV University of Regina News and Communications Backgrounder CONVOCATION PROFILES The Honorable Alvin Hamilton The Honorable Alvin Hamilton was born in Kenora, Ontario, on March 30, 1912. He attended public school in Kenora, high school in Delisle, Saskatchewan, Normal School in Saskatoon and taught school there from 1931 to 1934. He received his BA from the University of Saskatchewan in 1937, with an honors in history and economics in 1938. On November 14, 1936, he married the late Constance Beulah Florence, daughter of the late William John Major, and has two sons. His political canditure has included Rosetown-Biggar, 1945 and 1949; Rosetown 1948; Lumsden 1952; Qu'Appelle 1953; and he was the provincial candidate for Saskatoon in 1956. He was first elected to the House of Commons for Qu'Appelle in June 1957, appointed Minister of Northern Affairs and National Resources in August 1957, and served as Minister of Agriculture from October 1960 to April 1963. He was a candidate for Regina East in June 1968, and elected for Qu'Appelle-Moose Mountain in October 1972, retiring in 1988. Since then he has been provincial organizer and provincial leader for the Conservative Party in Saskatchewan. He served with the RCAF in WWII, and is a member of the Royal Canadian Legion and the RCAF association. Mrs. Alice Jenner Mrs. Jenner has a B.Sc.(H.E.) from the University of Manitoba; is a graduate of the United Church Training School (Convenant College), University of Toronto; served a dietetic internship at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto; and is a graduate of the Language School (Chinese Language) at the University of West China. -

Debates of the Senate

CANADA Debates of the Senate 1st SESSION . 39th PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 143 . NUMBER 108 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Thursday, June 14, 2007 ^ THE HONOURABLE NOËL A. KINSELLA SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates and Publications: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from PWGSC ± Publishing and Depository Services, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S5. Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 2669 THE SENATE Thursday, June 14, 2007 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the chair. government reach out to seniors' communities so that we can break down the wall of silence and show Canadians that elder Prayers. abuse exists, that it is not tolerated and that there is help available in our communities. SENATORS' STATEMENTS [Translation] THE HONOURABLE DAN HAYS, P.C. WORLD ELDER ABUSE AWARENESS DAY TRIBUTE Hon. Marjory LeBreton (Leader of the Government and Secretary of State (Seniors)): Honourable senators, on Hon. Pierre De Bané: Honourable senators, I rise today to pay June 15, 2007, Canadians will join together to recognize the tribute to Senator Dan Hays, who will soon be retiring. second annual World Elder Abuse Awareness Day. As you all know, Senator Hays has been sitting in this chamber World Elder Abuse Awareness Day was first declared last year as a senator for Alberta for almost 23 years. During this time, by the World Health Organization and the International Network Senator Hays was Deputy Leader of the Government in the for the Prevention of Elder Abuse. It is an opportunity to raise Senate, Speaker of the Senate and Leader of the Opposition in awareness of the abuse of older adults as a means to prevent the Senate. -

Federal-Provmcial Relations. the Canadian -At Board

COOPERATION AND CONFLICT: FEDERAL-PROVMCIAL RELATIONS. THE CANADIAN -AT BOARD. AND THE MARKETING OF PRPJRIE WKEAT Peter N. Ropke Department of Political Science Submitted in partial fulfülment of the degree of Master of Arts Facule of Graduate Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario July 1997 O Peter N. Ropke 1997 National Library Biblioth&que nationale of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, nie Wellington OttawaON K1AON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive Licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be p~tedor othenirise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This thesis attempts to explain both the unusual degree of federal-provincial harmony that had traditionally been evident in the area of prairie wheat marketing and the federal- provincial conflict that emereed in the IWO'S. It applies interest goup. globalization and govenunent-building approaches to explain federal-provincial relations conceming the marketing of prairie wheat and the Canadian Wheat Board. -

Water from the North

WATER FROM THE NORTH NATURE, FRESHWATER, AND THE NORTH AMERICAN WATER AND POWER ALLIANCE By Andrew W. Reeves A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Geography University o f Toronto © Copyright by Andrew W. Reeves 2009 WATER FROM THE NORTH: NATURE, FRESHWATER, AND THE NORTH AMERICAN WATER AND POWER ALLIANCE Master of Arts Andrew W. Reeves, 2009 Department of Geography University of Toronto Thesis Abstract The North American Water and Power Alliance (NAWAPA), a high modernist continental water diversion project drafted in Los Angeles in 1964, is examined for the impact it had upon social conceptions of nature, the scale of water diversion in North America, and the extent of American Southwestern efforts at sustaining unsustainable Northern lifestyles. Drafted to address the anxiety of perceived ecoscarcity regarding water shortages in the early 1960s, NAWAPA emerged after a century of increasingly large‐scale diversion projects, and seemed a logical continuation of such grandiose, “jet‐ age” type thinking. It proposed to re‐engineer the North American landscape to provide water from the North to the arid Southwest. Reasons for the plans failure (including the monumental shift in scale, and Canadian territorial and environmental opposition) are examined in relation to how nature was conceived – or forgotten – in the proposal. Keywords: freshwater; nature; resources; North America; high modernism; the “West.” ii Thesis Contents Thesis Abstract – pg. ii Thesis Contents – pg. iii List of Tables and Figures (Organized by Chapter) – pg. iv List of Abbreviations – pg. v Introduction pg. 1 Chapter One Theorizing NAWAPA – pg. -

By Ross Strick a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies And

CANADIAN IN!IXRNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS POLICY: THE CASES OF CUBA AND CHINA by Ross Strick A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research through the Department of Political Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada (C) 1997 National Libmry Bibliothèque nationaie 1*1 ofCanada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Weilington OttawaON K1AM ût&waON K1AON4 Canâda canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distriiuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfichelfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor su.bstantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. The purpose of this study is to examine the international human rights policy of Canada with respect to that of the United States. The assumption is made that given the fact that Canada and the United States share many similarities with respect to culture and ideology, the human rights policies which they adopt should also be very similar. -

Northern Vision: Northern Development During the Diefenbaker Era

Northern Vision: Northern Development during the Diefenbaker Era by Philip Isard A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2010 © Philip Isard 2010 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract At the inauguration of John G. Diefenbaker’s 1958 election campaign, the Prime Minister announced his ‘Northern Vision,’ a bold strategy to extend Canadian nationhood to the Arctic and develop its natural resources for the benefit of all Canadians. In some ways, the ‘Northern Vision’ was a political platform, an economic platform as well as an ideological platform. Invigorated by Diefenbaker’s electoral victory in 1958, the Department of Northern Affairs and National Development (DNANR) implementing the ‘National Development Policy’ in 1958 and announced the ‘Road to Resources’ program as a major effort to unlock the natural resource potential of the Canadian north. From 1958 to 1962, DNANR implemented additional northern development programs that planned to incorporate the northern territories along with Canada’s provinces, redevelop several key northern townsites, and stimulate mining activity across Northern Canada. As a result of serious government oversight and unforeseen developments, Diefenbaker abandoned his ‘Northern Vision’ and direction of northern development in 1962. Within the broader context of northern development over the past half century, the ‘Northern Vision’ produced several positive outcome which advanced the regional development of the Arctic. -

Proquest Dissertations

WATER FROM THE NORTH NATURE, FRESHWATER, AND THE NORTH AMERICAN WATER AND POWER ALLIANCE By Andrew W. Reeves A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Geography University of Toronto © Copyright by Andrew W. Reeves 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-59557-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-59557-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

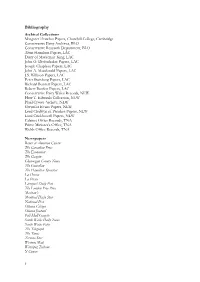

Bibliography

Bibliography Archival Collections Margaret Thatcher Papers, Churchill College, Cambridge Conservative Party Archives, BLO Conservative Research Department, BLO Alvin Hamilton Papers, LAC Diary of Mackenzie King, LAC John G. Diefenbaker Papers, LAC Joseph Chapleau Papers, LAC John A. Macdonald Papers, LAC J.S. Willison Papers, LAC Peter Stursberg Papers, LAC Richard Bennett Papers, LAC Robert Borden Papers, LAC Conservative Party Wales Records, NLW Huw T. Edwards Collection, NLW Plaid Cymru Archive, NLW Gwynfor Evans Papers, NLW Lord Cledwyn of Penrhos Papers, NLW Lord Crickhowell Papers, NLW Cabinet Office Records, TNA Prime Minister‟s Office, TNA Welsh Office Records, TNA Newspapers Baner ac Amserau Cymru The Canadian Press The Economist The Gazette Glamorgan County Times The Guardian The Hamilton Spectator La Devoir La Presse Liverpool Daily Post The London Free Press Maclean’s Montreal Daily Star National Post Ottawa Citizen Ottawa Journal Pall Mall Gazette South Wales Daily News South Wales Echo The Telegraph The Times Toronto Star Western Mail Winnipeg Tribune Y Cymro 1 Interviews Dr. Hywel Williams (11/07/11) Rt. Hon. Lord Crickhowell (29/06/11) Rt. Hon. Lord Hunt of Wirral (29/06/11) Rt. Hon. Lord Roberts of Conwy (8/04/11) Alun Cairns MP (29/03/11) Guto Bebb MP (29/03/11) David Davies MP 29/03/11) Glyn Davies MP (29/03/11) Professor Tom Flanagan (01/11/10) Primary and Secondary Sources Adams, J., Clark, M., Ezrow, L. and Glasgow, G. „Understanding Change and Stability in Party Ideologies: Do Parties Respond to Public Opinion or to Past Election Results?,‟ British Journal of Political Science, 34 (2004), pp.