Global War - Local Views

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Maya Ayana, "Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626527. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nf9f-6h02 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, Georgetown University, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, George Mason University, 2002 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2007 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Maya Ayana Johnson Approved by the Committee, February 2007 y - W ^ ' _■■■■■■ Committee Chair Associate ssor/Grey Gundaker, American Studies William and Mary Associate Professor/Arthur Krrtght, American Studies Cpllege of William and Mary Associate Professor K im b erly Phillips, American Studies College of William and Mary ABSTRACT In recent years, a number of young female pop singers have incorporated into their music video performances dance, costuming, and musical motifs that suggest references to dance, costume, and musical forms from the Orient. -

The Korea Press the Korea Press

The Korea Press The Korea Press Publisher Kim Byung-ho Editor in Chief Woo Deuk-jung Managing Editor Lee Sang-heun Tel 82-2-2001-7757 Email [email protected] Translated by Yang Sung-jin (Editor of The Korea Herald) Copyedited by Elaine Ramirez (Copy Editor of The Korea Herald) Chung Yong-kuk (Professor, Dept. of Journalism & Mass Communication, Dongguk Univ.) Published by Korea Press Foundation www.kpf.or.kr Korea Press Foundation 12-15F., Korea Press Center 124 Sejong-daero, Jung-gu, Seoul, Korea First Edition December 2015 Copyright © 2015 by Korea Press Foundation Designed by Nine Communication ISBN 978-89-5711-401-8 Content Chapter 1. 2014/2015 Korean Media Overview … 04 Chapter 2. Media Market … 22 Chapter 3. Media Workers … 30 Chapter 4. Print Newspaper Market … 40 Chapter 5. Broadcasting Market … 44 Chapter 6. Internet Newspaper Market … 55 Chapter 7. Media Audience : Pattern and Evaluation … 61 Chapter 8. Current Situation of Newspaper Industry Support … 70 Appendix 1. Overseas Branches of the Korean Media … 72 Appendix 2. Korean Correspondents Overseas … 74 Appendix 3. Foreign Correspondents in Korea … 79 Appendix 4. Directory … 86 Chapter 1 2014/2015 Korean Media Overview • Newspaper unique production practices that are formed over time. News media must overhaul the news pro- duction system to tailor it to a rapidly changing Attempt to depart from ‘exposure- media environment while preserving traditional first’ strategy news values; if not, they are unlikely to turn a profit in the fast-evolving media market. Against The “digital-first” strategy adopted by South this backdrop, it is a positive development Korean news media reflects the ongoing shift that Korean media are noticeably investing in in news consumption toward mobile media. -

So Much to Be Thankful for What to Expect

Broadcaster MAR 2007 ISSN: 1675 - 4751 VOLUME 6 NO.1 SO MUCH TO BE THANKFUL FOR This year, AIBD celebrates 30 years of service to broadcasting in Asia-Pacific. At age 30, AIBD has so much to be thankful for, notably the participation & support of member countries, affiliate members and partners for the Institute’s sustained initiatives to build human resource in broadcasting. From 1972 to 2006, the Institute conducted 735 regional training courses and seminars, and 588 in-country training workshops in Asia-Pacific. Benefiting from these activities were 12,244 regional and 10,426 in-country participants belonging to 43 organisations from AIBD’s 26 member-countries and 52 affiliate members across continents. It attracted a wide range of partners and funders, more than 250 organisations from (right photo), founding AIBD director, said that “every Asia, Pacific, Europe, America and the Arab professional should be involved in a training course world, keen to help create a more vibrant and of some kind at least every two or three years in his dynamic electronic media environment. career”. Dr. Javad Mottaghi, AIBD director, said At age 30, AIBD faces many more challenges. It managing the organisational and human will continue to direct its resources to broadcast factors inherent in a rapidly changing media training as its core function. Its focus will be environment, notably skills upgrading for new determined strongly by the challenges members entrants remains a major challenge for foresee in the industry. For this edition of the broadcasters. newsletter, we asked CEOs of media networks In an article he wrote in 1981, Mr. -

The Paleoecology and Fire History from Crater Lake

THE PALEOECOLOGY AND FIRE HISTORY FROM CRATER LAKE, COLORADO: THE LAST 1000 YEARS By Charles T. Mogen A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science and Policy Northern Arizona University August 2018 Approved: R. Scott Anderson, Ph.D., Chair Nicholas P. McKay, Ph.D. Darrell S. Kaufman, Ph.D. Abstract High-resolution pollen, plant macrofossil, charcoal and pyrogenic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) records were developed from a 154 cm long sediment core collected from Crater Lake (37.39°N, 106.70°W; 3328 m asl), San Juan Mountains, Colorado. Several studies have explored Holocene paleo-vegetation and fire histories from mixed conifer and subalpine bogs and lakes in the San Juan and southern Rocky Mountains utilizing both palynological and charcoal studies, but most have been at relatively low resolution. In addition to presenting the highest resolution palynological study over the last 1000 years from the southern Rocky Mountains, this thesis also presents the first high-resolution pyrogenic PAH and charcoal paired analysis aimed at understanding both long-term fire history and the unresolved relationship between how each of these proxies depict paleofire events. Pollen assemblages, pollen ratios, and paleofire activity, indicated by charcoal and pyrogenic PAH records, were used to infer past climatic conditions. Although the ecosystem surrounding Crater Lake has remained a largely spruce (Picea) dominated forest, the proxies developed in this thesis suggest there were two distinct climate intervals between ~1035 to ~1350 CE and ~1350 to ~1850 CE in the southern Rocky Mountains, associated with the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA) and Little Ice Age (LIA) respectively. -

BBC TV\S Panorama, Conflict Coverage and the Μwestminster

%%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and WKHµ:HVWPLQVWHU FRQVHQVXV¶ David McQueen This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. %%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and the µ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 µLet nation speak peace unto nation¶ RIILFLDO%%&PRWWRXQWLO) µQuaecunque¶>:KDWVRHYHU@(official BBC motto from 1934) 2 Abstract %%&79¶VPanoramaFRQIOLFWFRYHUDJHDQGWKHµ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen 7KH%%&¶VµIODJVKLS¶FXUUHQWDIIDLUVVHULHVPanorama, occupies a central place in %ULWDLQ¶VWHOHYLVLRQKLVWRU\DQG\HWVXUSULVLQJO\LWLVUHODWLYHO\QHJOHFWHGLQDFDGHPLF studies of the medium. Much that has been written focuses on Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRI armed conflicts (notably Suez, Northern Ireland and the Falklands) and deals, primarily, with programmes which met with Government disapproval and censure. However, little has been written on Panorama¶VOHVVFRQWURYHUVLDOPRUHURXWLQHZDUUeporting, or on WKHSURJUDPPH¶VPRUHUHFHQWKLVWRU\LWVHYROYLQJMRXUQDOLVWLFSUDFWLFHVDQGSODFHZLWKLQ the current affairs form. This thesis explores these areas and examines the framing of war narratives within Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRIWKH*XOIFRQIOLFWV of 1991 and 2003. One accusation in studies looking beyond Panorama¶VPRUHFRQWHQWLRXVHSLVRGHVLVWKDW -

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

Annual Report 2006-2008 FINAL

WEATHERHEAD CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS H A R V A R D U N I V E R S I T Y two2006-2007 thousand six – two thousand seven ANNUAL REPORTS two2007-2008 thousand seven – two thousand eight 1737 Cambridge Street • Cambridge, MA 02138 www.wcfia.harvard.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS PEOPLE 2 Advisory Committee 2 Executive Committee 2 Administration 3 RESEARCH ACTIVITIES 5 Small Grants for Faculty Research Projects 5 Medium Grants for Faculty Research Projects 5 Large Grants for Faculty Research Projects 5 Large Grants for Faculty Research Semester Leaves 6 Junior Faculty Synergy Semester Leaves 7 Distinguished Lecture Series 8 Weatherhead Initiative in International Affairs 8 CONFERENCES 10 STUDENT PROGRAMS 31 RESEARCH SEMINARS 45 Africa Research Seminar 45 Challenges Of The Twenty-First Century: European And American Perspectives 46 Communist and Postcommunist Countries Seminar 47 Comparative Politics Research Workshop 47 Comparative Politics Seminar 52 Cultural Politics: Interdisciplinary Pespectives Seminar 52 Director’s Faculty Seminar 53 Economic Growth and Development Workshop 53 Economic History Workshop 54 Ethics And International Relations Seminar 56 Faculty Discussion Group On Political Economy 56 Futue of War Seminar 63 Herbert C. Kelman Seminar on International Conflict Analysis and Resolution 63 International Business Seminar 65 International Economics Workshop 66 International History Seminar 68 International Law and International Relations Seminar 70 Middle East Seminar 71 Political Violence and Civil War 73 Religion and Society 75 Research Workshop in International Relations 75 Research Workshop on Political Economy 77 Science and Society Seminar 83 South Asia Seminar 84 Southeast Asia Security and International Relations 85 Transatlantic Relations Semimar 85 U.S. -

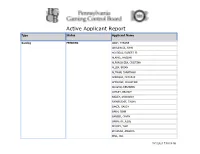

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name Gaming PENDING ABAH, TYRONE ABULENCIA, JOHN AGUDELO, ROBERT JR ALAMRI, HASSAN ALFONSO-ZEA, CRISTINA ALLEN, BRIAN ALTMAN, JONATHAN AMBROSE, DEZARAE AMOROSE, CHRISTINE ARROYO, BENJAMIN ASHLEY, BRANDY BAILEY, SHANAKAY BAINBRIDGE, TASHA BAKER, GAUDY BANH, JOHN BARBER, GAVIN BARRETO, JESSE BECKEY, TORI BEHANNA, AMANDA BELL, JILL 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BENEDICT, FREDRIC BERNSTEIN, KENNETH BIELAK, BETHANY BIRON, WILLIAM BOHANNON, JOSEPH BOLLEN, JUSTIN BORDEWICZ, TIMOTHY BRADDOCK, ALEX BRADLEY, BRANDON BRATETICH, JASON BRATTON, TERENCE BRAUNING, RICK BREEN, MICHELLE BRIGNONI, KARLI BROOKS, KRISTIAN BROWN, LANCE BROZEK, MICHAEL BRUNN, STEVEN BUCHANAN, DARRELL BUCKLEY, FRANCIS BUCKNER, DARLENE BURNHAM, CHAD BUTLER, MALKAI 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BYRD, AARON CABONILAS, ANGELINA CADE, ROBERT JR CAMPBELL, TAPAENGA CANO, LUIS CARABALLO, EMELISA CARDILLO, THOMAS CARLIN, LUKE CARRILLO OLIVA, GERBERTH CEDENO, ALBERTO CENTAURI, RANDALL CHAPMAN, ERIC CHARLES, PHILIP CHARLTON, MALIK CHOATE, JAMES CHURCH, CHRISTOPHER CLARKE, CLAUDIO CLOWNEY, RAMEAN COLLINS, ARMONI CONKLIN, BARRY CONKLIN, QIANG CONNELL, SHAUN COPELAND, DAVID 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING COPSEY, RAYMOND CORREA, FAUSTINO JR COURSEY, MIAJA COX, ANTHONIE CROMWELL, GRETA CUAJUNO, GABRIEL CULLOM, JOANNA CUTHBERT, JENNIFER CYRIL, TWINKLE DALY, CADEJAH DASILVA, DENNIS DAUBERT, CANDACE DAVIES, JOEL JR DAVILA, KHADIJAH DAVIS, ROBERT DEES, I-QURAN DELPRETE, PAUL DENNIS, BRENDA DEPALMA, ANGELINA DERK, ERIC DEVER, BARBARA -

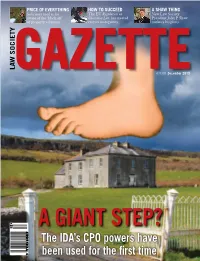

The IDA's CPO Powers Have Been Used for the First Time

LAW LAW PRICE OF EVERYTHING HOW TO SUCCEED A SHAW THING S OCIETY GAZETTE Solicitors need to be The EU Regulation on New Law Society aware of the ‘black art’ Succession Law has created President John P Shaw of property valuation certain ambiguities outlines his plans • Vol 107 No 10 • Vol LAW SOCIETY LAW GAZETTEGAZETTE€4.00 December 2013 D ECE MB ER 2013 A GIANT STEP? Law Society of Ireland The IDA’s CPO powers have been used for the first time Two new criminal titles from Evidence in Police Powers Criminal Trials in Ireland by Liz Heffernan with Úna Ní Raifeartaigh SC by Garnet Orange The first Irish textbook devoted exclusively Irish policing law and practice has seen great to the subject of criminal evidence reform over the past 20 years. This new title will provide you with comprehensive, detailed Police Powers in Ireland is a new, hands-on guide that coverage of law and practice on the admissibility of will help you keep abreast of developments in this area. It evidence, the presentation of evidence in court and the explains and explores the powers that are available to the pre-trial gathering and disclosure of evidence. Gardaí for the investigation of serious offences. Wide-ranging coverage Covers the following key areas: The work combines analysis of traditional evidentiary n Judges’ Rules and the questioning of suspects doctrine with discussion of its application in practice. n Adverse inference The topics covered include: n Police powers to enter property and powers to search n The examination of witnesses that property n Expert evidence n Stop and search of vehicles n Custodial statements n Observation, surveillance and phone-tapping n Unlawfully obtained evidence and interception n The rule against hearsay n The seizure and retention of evidence n The testimony of children n Forensic evidence n Visual ID You’ll also find coverage of n Entrapment developments such as the cross- examination of the accused, n Trial and remedies previous witness statements and n Garda Ombudsman DNA evidence. -

Judging Panel for 2021 Royal Society Science Book Prize Announced

**For release Wednesday 21stJuly** JUDGING PANEL FOR 2021 ROYAL SOCIETY SCIENCE BOOK PRIZE ANNOUNCED “Science communication has always been very important, to entertain, inform and inspire. This has never been more relevant than this year.” – Professor Luke O’Neill #SciBooks The five-strong judging panel for this year’s Royal Society Science Book Prize, sponsored by Insight Investment, is revealed today, Wednesday 21st July 2021. The Prize – which celebrates the very best in popular science writing from around the world – will be chaired in 2021 by world-leading immunologist, presenter and writer, Professor Luke O’Neill FRS. He is joined on the panel by representatives from across the worlds of science and culture: television presenter, Ortis Deley; mathematician and Dorothy Hodgkin Royal Society Fellow, Dr Anastasia Kisil; author and creative writing lecturer, Christy Lefteri, and journalist, writer and film maker, Clive Myrie. For 33 years, the Prize has promoted the accessibility and joy of popular science writing. It has celebrated some truly game-changing reads: books that offer fresh insights on the things that affect the lives we lead and the decisions we make, from neurodiverse perspectives on everyday living (Explaining Humans by Dr Camilla Pang, 2020) to gender bias (Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez, 2019) and the harms humans are wreaking on the planet (Adventures in the Anthropocene by Gaia Vince, 2015, and Six Degrees by Mark Lynas, 2008). In 2021, the judges renew their search for the most compelling science writing of the last year, at a time when the power of effective science communication is valued more highly than ever before. -

Glossary Ahengu Shkodran Urban Genre/Repertoire from Shkodër

GLOSSARY Ahengu shkodran Urban genre/repertoire from Shkodër, Albania Aksak ‘Limping’ asymmetrical rhythm (in Ottoman theory, specifically 2+2+2+3) Amanedes Greek-language ‘oriental’ urban genre/repertory Arabesk Turkish vocal genre with Arabic influences Ashiki songs Albanian songs of Ottoman provenance Baïdouska Dance and dance song from Thrace Čalgiya Urban ensemble/repertory from the eastern Balkans, especially Macedonia Cântarea României Romanian National Song Festival: ‘Singing for Romania’ Chalga Bulgarian ethno-pop genre Çifteli Plucked two-string instrument from Albania and Kosovo Čoček Dance and musical genre associated espe- cially with Balkan Roma Copla Sephardic popular song similar to, but not identical with, the Spanish genre of the same name Daouli Large double-headed drum Doina Romanian traditional genre, highly orna- mented and in free rhythm Dromos Greek term for mode/makam (literally, ‘road’) Duge pjesme ‘Long songs’ associated especially with South Slav traditional music Dvojka Serbian neo-folk genre Dvojnica Double flute found in the Balkans Echos A mode within the 8-mode system of Byzan- tine music theory Entekhno laïko tragoudhi Popular art song developed in Greece in the 1960s, combining popular musical idioms and sophisticated poetry Fanfara Brass ensemble from the Balkans Fasil Suite in Ottoman classical music Floyera Traditional shepherd’s flute Gaida Bagpipes from the Balkan region 670 glossary Ganga Type of traditional singing from the Dinaric Alps Gazel Traditional vocal genre from Turkey Gusle One-string, -

Lessons-Encountered.Pdf

conflict, and unity of effort and command. essons Encountered: Learning from They stand alongside the lessons of other wars the Long War began as two questions and remind future senior officers that those from General Martin E. Dempsey, 18th who fail to learn from past mistakes are bound Excerpts from LChairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: What to repeat them. were the costs and benefits of the campaigns LESSONS ENCOUNTERED in Iraq and Afghanistan, and what were the LESSONS strategic lessons of these campaigns? The R Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University was tasked to answer these questions. The editors com- The Institute for National Strategic Studies posed a volume that assesses the war and (INSS) conducts research in support of the Henry Kissinger has reminded us that “the study of history offers no manual the Long Learning War from LESSONS ENCOUNTERED ENCOUNTERED analyzes the costs, using the Institute’s con- academic and leader development programs of instruction that can be applied automatically; history teaches by analogy, siderable in-house talent and the dedication at the National Defense University (NDU) in shedding light on the likely consequences of comparable situations.” At the of the NDU Press team. The audience for Washington, DC. It provides strategic sup- strategic level, there are no cookie-cutter lessons that can be pressed onto ev- Learning from the Long War this volume is senior officers, their staffs, and port to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman ery batch of future situational dough. The only safe posture is to know many the students in joint professional military of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and unified com- historical cases and to be constantly reexamining the strategic context, ques- education courses—the future leaders of the batant commands.