Maleme to Sphakia — Evacuation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crown Copyright Catalogue Reference

(c) crown copyright Catalogue Reference:cab/66/9/30 Image Reference:0001 THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT SECRET. Copy,No. 26 W.P. (40) 250 (Also Paper No. C.O.S. (40) 534) July 5, 1940 TO BE KEPT UNDER LOCK It is requested that special care mai be ta&en to ensure the secrecy of this document T" o, 44) of the from 12 noon June 27th to 12 noon July 4th, [Circulated with the approval of the Chiefs of Staff.] Cabinet War Room. NAYAL SITUATION. General Review. THE outstanding event in the Naval Situation during the past week has been the action taken to prevent the French Fleet falling into enemy hands. At least 4 Italian submarines and one destroyer have been sunk in the Mediterranean. There has been a considerable reduction in the number of German U-boats on patrol. French Fleet. 2. The French failure to comply with their undertaking to prevent their fleet falling into the hands of our enemies as a result of the armistice necessitated action by us to that end on the 3rd July, on which, date the disposition of the principal French naval forces was as shown in Appendix IV. All vessels in British ports were seized. At Plymouth the seizure was effected without incident except for the submarine Surcouf, where 2 British officers were seriously wounded and 1 rating killed and 1 wounded. One French officer was also killed and 1 wounded. At Portsmouth a leaflet raid was carried out on the French ships for the crews' information and the ships successfully seized. -

HMS Caprice Association

HMS Caprice (World Cruise 1968) Association Commander Tim Bevan Sept 2019 Issue No 72 HMS Caprice 1968 Association Newsletter 72 Sept. 2019 In This Issue 2020 Reunions Past Reunions Association Website After the Cruise was over PayPal account Pedro’s Poem - Stage 5 RIP - Tim Bevan D01 - the model Our Cruise Skippers The Queen’s Navy 2019 Tamworth Weekend Finance Report 2019 Reunion at Bristol Slops The cover features our original Skipper, the late Tim Bevan when he was Captain of the Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth 2020 Reunions The Tamworth Weekend will be on 5-7th June 2020. The date and venue of the Main Reunion is not fixed as yet. We need to assess how the 2019 reunion with IOW Tours goes before a decision is made. Association Website www.hmscaprice1968.org.uk Our website is kept fully up to date and you can view newsletters online. It has had over 25300 hits to date and has attracted many new members. There is also a very good picture archive of the Caprice from 1942 to 1979, and up to date Association & Reunion News. The Association has a PayPal account which is a simple way of transferring payments into our bank account for purchases or subs, especially if you are an overseas member. Just use [email protected] 2 HMS Caprice 1968 Association Newsletter 72 Sept. 2019 RIP Tim Bevan Rear-Admiral Tim Bevan, born April 7 1931, died June 6 2019 His first appointment at sea was the cruiser HMS Glasgow in the West Indies: his promise was quickly recognised, and he went as Sub-Lieutenant of the gunroom, a very responsible job for a junior officer. -

Model Ship Book 4Th Issue

A GUIDE TO 1/1200 AND 1/1250 WATERLINE MODEL SHIPS i CONTENTS FOREWARD TO THE 5TH ISSUE 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 2 Aim and Acknowledgements 2 The UK Scene 2 Overseas 3 Collecting 3 Sources of Information 4 Camouflage 4 List of Manufacturers 5 CHAPTER 2 UNITED KINGDOM MANUFACTURERS 7 BASSETT-LOWKE 7 BROADWATER 7 CAP AERO 7 CLEARWATER 7 CLYDESIDE 7 COASTLINES 8 CONNOLLY 8 CRUISE LINE MODELS 9 DEEP “C”/ATHELSTAN 9 ENSIGN 9 FIGUREHEAD 9 FLEETLINE 9 GORKY 10 GWYLAN 10 HORNBY MINIC (ROVEX) 11 LEICESTER MICROMODELS 11 LEN JORDAN MODELS 11 MB MODELS 12 MARINE ARTISTS MODELS 12 MOUNTFORD METAL MINIATURES 12 NAVWAR 13 NELSON 13 NEMINE/LLYN 13 OCEANIC 13 PEDESTAL 14 SANTA ROSA SHIPS 14 SEA-VEE 16 SANVAN 17 SKYTREX/MERCATOR 17 Mercator (and Atlantic) 19 SOLENT 21 TRIANG 21 TRIANG MINIC SHIPS LIMITED 22 ii WASS-LINE 24 WMS (Wirral Miniature Ships) 24 CHAPTER 3 CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURERS 26 Major Manufacturers 26 ALBATROS 26 ARGONAUT 27 RN Models in the Original Series 27 RN Models in the Current Series 27 USN Models in the Current Series 27 ARGOS 28 CM 28 DELPHIN 30 “G” (the models of Georg Grzybowski) 31 HAI 32 HANSA 33 NAVIS/NEPTUN (and Copy) 34 NAVIS WARSHIPS 34 Austro-Hungarian Navy 34 Brazilian Navy 34 Royal Navy 34 French Navy 35 Italian Navy 35 Imperial Japanese Navy 35 Imperial German Navy (& Reichmarine) 35 Russian Navy 36 Swedish Navy 36 United States Navy 36 NEPTUN 37 German Navy (Kriegsmarine) 37 British Royal Navy 37 Imperial Japanese Navy 38 United States Navy 38 French, Italian and Soviet Navies 38 Aircraft Models 38 Checklist – RN & -

Research Organizations in British Shipbuilding and Large Marine

Research Organisations in British Shipbuilding and Large Marine Engine Manufacture: 1945-1959 (Part II) Hugh Murphy Cet article fait suite à la première partie, qui traitait de la période 1900 à 1944. Ici, l’auteur étudie l’impact de la British Ship Research Association, de la Parsons Marine Turbine Research and Development Association et, de façon tangentielle, d’un groupe de conseil en recherche privé, le Yarrow Admiralty Research Department (Y-ARD), une filiale de Yarrow Shipbuilders établie dans le district Scotstoun de la rivière Upper Clyde, et le National Physical Laboratory (NPL). Il traite également de William Doxford & Sons, avant d’évaluer l’impact individuel et collectif de ces sociétés jusqu’en 1959, ainsi que la situation générale de la construction navale britannique et la fabrication de gros moteurs maritimes. This article follows on directly from Part 1 covering the period 1900-1944, published in the last issue. Here I examine the impact of the British Ship Research Association (BSRA) and Parsons Marine Turbine Research and Development Association (PAMETRADA). Tangentially I review one private research consultancy cluster, the Yarrow Admiralty Research Department (YARD) an offshoot of Yarrow Shipbuilders, Scotstoun, on the Upper Clyde, and the National Physical Laboratory (NPL). I also consider Wm Doxford & Sons, before assessing their individual and collective impact up to 1959, and the general situation in British shipbuilding and large marine engine manufacture. The Northern Mariner / Le marin du nord, XXX, No. 2 (Summer -

Artifacts of Exchange: a Multiscalar Approach to Maritime Archaeology at Elmina, Ghana

Syracuse University SURFACE Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Anthropology - Dissertations Affairs 2011 Artifacts of Exchange: A Multiscalar Approach to Maritime Archaeology at Elmina, Ghana Andrew T. Pietruszka Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/ant_etd Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Pietruszka, Andrew T., "Artifacts of Exchange: A Multiscalar Approach to Maritime Archaeology at Elmina, Ghana" (2011). Anthropology - Dissertations. 87. https://surface.syr.edu/ant_etd/87 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses on the excavation and interpretation of two European ships discovered at Elmina Ghana, the coastal site of the first and largest European fort in sub-Saharan Africa. Discovered in 2003, the first vessel, located 1.5 miles offshore of the castle, is largely comprised of remnants of cargo exposed on the seafloor. European trade wares recovered from the site suggest a mid-seventeenth century vessel, most likely of Dutch origin. AMS radiocarbon dates obtained from several fragments of wood recovered in cores taken at the site support this assumption. The second vessel was discovered by accident during the 2007 dredging of the Benya River, a small lagoonal system that empties into the sea at Elmina. Largely destroyed during the operation, identifiable remains included fifteen timbers and three cannon. Dendrochronology and ship construction techniques indicate the remains to be those of an early eighteenth century Dutch vessel. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

The London Gazette of TUESDAY, the Isth of MAY, 1948 by Registered As a Newspaper

Wumb« 38293 3041 SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette Of TUESDAY, the iSth of MAY, 1948 by Registered as a newspaper WEDNESDAY, 19 MAY, 1948 TRANSPORTATION OF THE ARMY TO GREECE AND EVACUATION OF THE ARMY FROM GREECE, 1941. TRANSPORTATION OF THE ARMY TO men or equipment were lost at sea-except for GREECE. a few casualties from bomb splinters in one The following Despatch was submitted to the merchant ship. The losses sustained were either Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty on in ships proceeding in the convoys but not con- the nth December, 1941,' by Admiral Sir nected with " Lustre " or in ships jreturning Andrew B. Cunningham, G.C.B., D.S.O., empty (see Appendix). Commander-in-chief, Mediterranean Station. 4. During the greater part of the move a •Mediterranean. proportion of the Battle Fleet was kept at sea to the westward of Crete to provide heavy cover nth December, 1941. for our forces. In addition, Operation M.C.g, OPERATION " LUSTRE ". running a Malta convoy, was carried out between igth and 24th March whilst " Lustre " Be pleased to lay before Their Lordships still proceeded. *He following report concerning Operation "\ Lustre "—the move .to Greece of some 58,000 5. The whole operation was smoothly carried out owing to the 'hard work and willing spirit tr'iops with their mechanical transport, full v equipment and stores. The operation com- shown in the ships concerned. It threw a con- menced on 4th March and ceased on 24th April siderable strain on the port of Alexandria where when the evacuation from Greece commenced. -

Of Deaths in Service of Royal Naval Medical, Dental, Queen Alexandra's Royal Naval Nursing Service and Sick Berth Staff

Index of Deaths in Service of Royal Naval Medical, Dental, Queen Alexandra’s Royal Naval Nursing Service and Sick Berth Staff World War II Researched and collated by Eric C Birbeck MVO and Peter J Derby - Haslar Heritage Group. Ranks and Rate abbreviations can be found at the end of this document Name Rank / Off No 1 Date Ship, (Pennant No), Type, Reason for loss and other comrades lost and Rate burial / memorial details (where known). Abel CA SBA SR8625 02/10/1942 HMS Tamar. Hong Kong Naval Base. Drowned, POW (along with many other medical shipmates) onboard SS Lisbon Maru sunk by US Submarine Grouper. 2 Panel 71, Column 2, Plymouth Naval Memorial, Devon, UK. 1 Officers’ official numbers are not shown as they were not recorded on the original documents researched. Where found, notes on awards and medals have been added. 2 Lisbon Maru was a Japanese freighter which was used as a troopship and prisoner-of-war transport between China and Japan. When she was sunk by USS Grouper (SS- 214) on 1 October 1942, she was carrying, in addition to Japanese Army personnel, almost 2,000 British prisoners of war captured after the fall of Hong Kong in December Name Rank / Off No 1 Date Ship, (Pennant No), Type, Reason for loss and other comrades lost and Rate burial / memorial details (where known). Abraham J LSBA M54850 11/03/1942 HMS Naiad (93). Dido-class destroyer. Sunk by U-565 south of Crete. Panel 71, Column 2, Plymouth Naval Memorial, Devon, UK. Abrahams TH LSBA M49905 26/02/1942 HMS Sultan. -

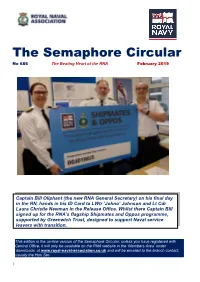

The Semaphore Circular No 686 the Beating Heart of the RNA February 2019

The Semaphore Circular No 686 The Beating Heart of the RNA February 2019 Captain Bill Oliphant (the new RNA General Secretary) on his final day in the RN, hands in his ID Card to LWtr ‘Johno’ Johnson and Lt Cdr Laura Christie Newman in the Release Office. Whilst there Captain Bill signed up for the RNA’s flagship Shipmates and Oppos programme, supported by Greenwich Trust, designed to support Naval service leavers with transition. This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec 1 Daily Orders (follow each link) Orders [follow each link] 1. Corporate Membership 2. National Ceremonial Advisor Vacancy 3. National Branch and Retention Advisor Area Assistants Vacancy 4. RNVC Series –Temporary Lieutenant Thomas Wilkinson VC 5. Travel Insurance 6. Portsmouth Historic Dockyard 7. Guess Where? 8. Joke – Painting the Church 9. Making Wills and Lasting Powers of Attorney 10. Finance Corner 11. Assistance Please – S/M Topsy Turner 12. Charity Donations 13. National Council Dining Out 14. Joke time – Flu Avoidance 15. A thousand good deeds a day 16. Fundraising Guidance 17. Hospital & Medical Care Association 18. Victory Walk Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice -

HMS Daring, Destroyer

HMS Daring, destroyer Naval History Homepage and Site Search SERVICE HISTORIES of ROYAL NAVY WARSHIPS in WORLD WAR 2 by Lt Cdr Geoffrey B Mason RN (Rtd) (c) 2004 HMS DARING (H 16) - D-class Destroyer including Convoy Escort Movements HMS Daring (Navy Photos/Michael Pocock, click to return to Contents List enlarge) D or DEFENDER-Class Fleet Destroyer ordered from John I Thornycroft at Woolston, Southampton in the 1930 Programme. The ship was laid down on 18th June 1931 and launched on 7th April 1932. She was the 5th RN ship to carry the name, introduced in 1801 and previously used by a destroyer sold in 1912. Build was completed on 25th November 1932 for a contract price of £225,536 excluding the Admiralty supplied equipment such as guns, ammunition and communications equipment. She joined the 1st Destroyer Flotilla in the Mediterranean early the next year. The ship re-commissioned in April 1934 after refit at Sheerness.. In December 1934 she sailed to join the 8th Destroyer Flotilla on the China Station and served there until the outbreak of war. Her captain until arrival at Singapore was the renowned Lord Louis Mountbatten. B a t t l e H o n o u r s None H e r a l d i c D a t a Badge: On a Field Black, an arm and a hand in a cresset of fire all Proper. M o t t o Splendide audax : 'Finely daring’ D e t a i l s o f W a r S e r v i c e (for more ship information, go to Naval History Homepage and type name in Site Search) 1 9 3 9 September 3rd Passage to join Fleet at Alexandria with HM Destroyers DUNCAN, DIANA and DAINTY. -

MMUNIGATOR L*A T€€, Lpfr;E

/":/.//rr-K. THE MMUNIGATOR l*a t€€, lpFr;e VOt 19-No. 3 i,& I !!jTF fr * **S LIGHTWEIGHI the Services newest highpower GIrfirfl EEctrtrill BCC "Against intense competition the BCC 30 has been selected to f ill the 414 role for the British Services." The Al tt--BCC 30 is the lightest, smallest, f ully transisto- rised, one man high power H F transmitter-receiver station with an output of up to 30 watts. Fully approved to British Ministry of Defence DEF 133 standards and to United States Mil.Std.1B8B the Alzt- BCC 30 has already been selected by the British Services, Commonwealth, NATO and United States forces. BNTIS'I COTMATICA|IOTE COBPONATruil LTI'. souTr{ wAY, EXHtBtTtON GROUNDS, WEMBLEY, MtDDLESEx Telephone: WEMbley 1212 Cables: BEECEECEE Wembley Better Deal with , , , DAUFMAN TAILORS AND OUTFITTERS TO THE ROYAL NAVY FOR OVER 50 YEARS H.M.S. ,.MERCURY'' SHOP (Manager: Mr. A. C. Waterman) We invite you to inspect the lorge rongeanti voried serection of Uniforms ond civilion Clothing in our Comp Shop Our Crested Pattern Communication Branch Ties are again available, l7s. 5d. each, in Terylene. CIVILIAN TAILORING STYLED TO YOUR INDIVIDUAL REQUIREMENTS PROMPT AND PERSONAL ATTENTION TO ALL ORDERS SPECIALISTS IN OFFICERS' UNIFORMS Novo/ Allotment ond other Credit focilities ovoilable GIFT CATALOGUE AVAILABLE ON REQUEST Heod Ofice: 20 QUEEN ST., PORTSMOUTH Telephone : PORTSMOUTH 22830 Members of the lnterport Naval Traders Association tt4 THE COMMUNICATOR The Magazine of the Communications Branch, Royal Navy and the Royal Naval Amateur Radio Society WINTER 1968 VOL. 19, No.3 CONTENTS page page Captain J. -

NEWSFLASH April 2021

NEWSFLASH April 2021 Hello Swamp Foxes, welcome to the April 2021 Newsletter Into April we go....... another month has come and gone...... It is hard to figure just what 2021 has in store for Us, One Model at a Time I guess........... 9th April 2021 saw another Royal Navy Veteran Pass away, Prince Philip, The Duke of Edinburgh who had a very active service, passed away peacefully in his sleep aged 99, Fair Winds and Following Seas Sir..... Some great builds and works in progress by our members can be seen in members models, Stay Safe, Hang in there and .............. Keep on Building From the Front Office… Howdy, all! The April Zoom meeting will be held on 21 April: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81633790135?pwd=S1UwTVlaaU9tejEzZmNOZElza2FSdz09 Mike Roof will present a demonstration on rigging for us this month. Speaking with the library, they still have not opened up meeting rooms or re-started programs. I will continue to keep checking in with them from month to month to see when we might actually begin to meet in person again. I will also ask them if we might be able to hold a “tailgate meeting” in the front corner of their parking lot—as long as we do not cause traffic issues, I think it might be an alternative to the meeting room. I will let you know how that goes. Granted, with the famously hot Columbia summers getting big in the window, we won’t be able to do this every month, but it is a possibility. **** **** **** **** **** **** As far as the June show goes, everything is still progressing towards that date.