Review of Zoos' Conservation and Education Contribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

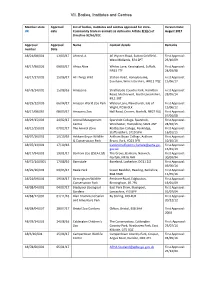

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Delivering a Sustainable International Visitors

Whitsun Campaign Delivering a Sustainable International Visitor Attraction…….a long road, with many successes and the odd bump! Creating Sustainable Tourism Destinations Ray Morrison, University of Chester Facilities & Environment Manager 9th July 2012 Chester Zoo Chester Zoo.......... Who are we? Our mission? Do we deliver? Do we operate the business sustainably? Key sustainability issues? Key achievements? Questions and Answers (maybe) Coffee and (maybe?) Who are we? Formed in 1934 Registered charity, conservation and education UK’s No. 1 Wildlife Attraction Top 15 zoos in World (Forbes Magazine) 1.4 million visitors in 2011 8,000 Animals, 400 different species 1,000 of Plants many endangered or rare Turnover £28 million per annum £1 million invested annually in conservation projects worldwide • Vision and Mission? Our Vision - A diverse, thriving and sustainable natural world Our Mission - To be a major force in conserving biodiversity worldwide Strategic Objective - To manage our work and activities to ensure long-term sustainability. Diverse and complex business Insight into our animal, plant, educational and environmental activities Do we deliver? ‘Sustainable’ …. Satisfying the needs of today without compromising tomorrow • Do we deliver on our mission? Evidence – Sustained achievements in line with our animal and plant conservation and educational goals, local and national. • Do we manage the Zoo’s operations sustainably? Evidence – ISO 14001, continual improvement, achieved various local and national awards Delivering -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

Managing Online Communications and Feedback Relating to the Welsh Visitor Attraction Experience: Apathy and Inflexibility in Tourism Marketing Practice?

Managing online communications and feedback relating to the Welsh visitor attraction experience: apathy and inflexibility in tourism marketing practice? David Huw Thomas, BA, PGCE, PGDIP, MPhil Supervised by: Prof Jill Venus, Dr Conny Matera-Rogers and Dr Nicola Palmer Submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the degree of PhD University of Wales Trinity Saint David. 2018 i ii DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for deposit in the University’s digital repository. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 iii iv Abstract Understanding of what constitutes a tourism experience has been the focus of increasing attention in academic literature in recent years. For tourism businesses operating in an ever more competitive marketplace, identifying and responding to the needs and wants of their customers, and understanding how the product or consumer experience is created is arguably essential. -

About Knowsley Safari

ABOUTABOUT THE KNOWSLEY KNOWSLEY SAFARI ESTATE Knowsley Safari is situated within the grounds of the Knowsley Estate. Animals and discovery have always been at the heart of the Estate – even before the safari park was ever created. Edward Smith Stanley, the 13th Earl of Derby, founding member of the Zoological Society of London and president for 20 years, built up a huge collection of birds, mammals and fish from around the world, many of which had never been seen in Britain before. At the time, Lord Derby’s private zoo became the largest and most important of its type in Britain and when he died, his menagerie was as big as 28 bird species and 94 animal species – and an impressive 756 animals bred at Knowsley. In October 1970, nearly 120 years later, the 18th Earl of Derby got permission to build a 346-acre wildlife and game reserve on part of the Estate. The first in the North of England and the first in a big city. Knowsley Safari Park opened in 1971 and quickly became one of the North West’s leading attractions, with new exhibits and the extension of the safari drive to 5 miles in 1973. In 1994, the 19th Earl of Derby took over and increased the visitor numbers and stepped-up participation in worldwide endangered species breeding programmes. Over the past few years, discussions have been underway to change the safari park as we know it now within the ‘Master Plan’. This includes ideas around new animal habitats, a visitor hub, better facilities for guests in the winter months, with attractions and adventure which enable us to be open more days throughout the year. -

Thirty Years Later: Enrichment Practices for Captive Mammals à Julia M

Zoo Biology 29 : 303–316 (2010) RESEARCH ARTICLE Thirty Years Later: Enrichment Practices for Captive Mammals à Julia M. Hoy, Peter J. Murray, and Andrew Tribe School of Animal Studies, The University of Queensland, Gatton Campus, Queensland, Australia Environmental enrichment of captive mammals has been steadily evolving over the past thirty years. For this process to continue, it is first necessary to define current enrichment practices and then identify the factors that limit enhancing the quality and quantity of enrichment, as well as the evaluation of its effectiveness. With the objective of obtaining this information, an international multi- institutional questionnaire survey was conducted with individuals working with zoo-housed mammals. Results of the survey showed that regardless of how important different types of enrichment were perceived to be, if providing them was particularly time-consuming, they were not made available to captive mammals as frequently as those requiring less staff time and effort. The groups of mammals provided with enrichment most frequently received it on average fewer than four times per day, resulting in less than two hours per day spent by each animal care staff member on tasks related to enrichment. The time required for staff to complete other husbandry tasks was the factor most limiting the implementation and evaluation of enrichment. The majority of survey respon- dents agreed that they would provide more enrichment and carry out more evaluation of enrichment if it was manageable to do so. The results of this study support the need for greater quantity, variety, frequency, and evaluation of enrichment provided to captive mammals housed in zoos without impinging on available staff time. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

A Stella Year the Park Is Celebrating Its 50Th Anniversary in 2020

2020 WILD TALKwww.cotswoldwildlifepark.co.uk New baby White Rhino Stella cuddles up to her mum Ruby Photo: Rory Carnegie Rory Photo: A Stella Year The Park is celebrating its 50th Anniversary in 2020. We hope to continue to inspire future Ruby and Stella walked out of the stall, giving generations to appreciate the beauty of the lucky visitors a glimpse of a baby White Rhino natural world. 2019 was a great year with Soon after the birth, Ruby and her new calf record visitor numbers, TV appearances, lots walked out of the stall into the sunshine of the of baby animals and a new Rhino calf. yard, giving a few lucky visitors a glimpse of a baby White Rhino less than two hours old. ighlights of the year included the Stella is doing well and Ruby has proved once Park featuring on BBC’s Springwatch again to be an exceptional mother. Having Hprogramme, with our part in the White another female calf is really important for the Storks’ UK re-introduction project. Then in European Breeding Programme of this iconic Astrid October, BBC Gardeners’ World featured the but endangered species. Park and presenter Adam Frost sang the praises OUR 6 RHINO CALVES of our gardens. To top off the year, Ruby gave White Rhinos have always been an important 1. Astrid born 1st July 2013, birth to our sixth Rhino calf in as many years, species at the Park, which was founded by John moved to Colchester Zoo. named “Stella”! Heyworth (1925-2012) in 1970. He had a soft spot 2. -

NICK ELLERTON 5 February 1949 – 29 March 2014

NICK ELLERTON 5 February 1949 – 29 March 2014 Obituary Sadly this reports that Nick really knew and cared about cook, a red wine lover and a loyal Ellerton died suddenly in the early animal welfare and was prepared friend. At times he had some morning of Saturday 29 March to be vocal about those issues. He outrageous opinions, strongly 2014, when he suffered a heart always put the needs of the expressed, but was always willing attack, in Sri Lanka. animals first and foremost, even to listen to challenges to those though it made him politically views, even if this did not always Nick worked as Deputy, then unpopular at times. He was a man shift his own. Curator of Mammals at the North ahead of his time in Zoos, and of England Zoological Society particularly drove changes in our Nick was probably the most (Chester Zoo) for 31 years before attitude to elephant welfare and observant person I have ever moving to Knowsley Safari Park for breeding so forcefully back in the known. He noticed everything. 11 years. Together with his 1980s. He was able to get a lot of He felt strongly about looking after longtime partner Penny Boyd progressive ideas around animal his own back yard before (formerly of Burstow Wildlife welfare started and worried little suggesting to other countries how Sanctuary in the UK, and latterly about the fallout for those who to look after theirs. He was also at Knowsley) they moved to were not prepared to change their realistic in the advice he offered to Sri Lanka in the summer of 2010 attitudes. -

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 Presents the Findings of the Survey of Visits to Visitor Attractions Undertaken in England by Visitbritain

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VisitBritain would like to thank all representatives and operators in the attraction sector who provided information for the national survey on which this report is based. No part of this publication may be reproduced for commercial purp oses without previous written consent of VisitBritain. Extracts may be quoted if the source is acknowledged. Statistics in this report are given in good faith on the basis of information provided by proprietors of attractions. VisitBritain regrets it can not guarantee the accuracy of the information contained in this report nor accept responsibility for error or misrepresentation. Published by VisitBritain (incorporated under the 1969 Development of Tourism Act as the British Tourist Authority) © 2004 Bri tish Tourist Authority (trading as VisitBritain) Cover images © www.britainonview.com From left to right: Alnwick Castle, Legoland Windsor, Kent and East Sussex Railway, Royal Academy of Arts, Penshurst Place VisitBritain is grateful to English Heritage and the MLA for their financial support for the 2003 survey. ISBN 0 7095 8022 3 September 2004 VISITOR ATTR ACTION TRENDS ENGLAND 2003 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS A KEY FINDINGS 4 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 12 1.1 Research objectives 12 1.2 Survey method 13 1.3 Population, sample and response rate 13 1.4 Guide to the tables 15 2 ENGLAND VISIT TRENDS 2002 -2003 17 2.1 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by attraction category 17 2.2 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by admission type 18 2.3 England visit trends -

Ks2 Sumatran Tiger Answers (Virtual Zoo Day)

LEARN AT KS2 SUMATRAN TIGER QUESTIONS (VIRTUAL ZOO DAY) After watching our Sumatran tigers as part of our Virtual Zoo Day, test your knowledge with the following questions. Write your answers as full sentences. QUESTION 1 What do tigers use their stripes for? .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. QUESTION 2 We have two Sumatran tigers, a mother and daughter, what are their names? ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. QUESTION 3 Orangutan Which special teeth help tigers to sheer through meat? .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. QUESTION 4 Sumatran tigers are the smallest subspecies of tiger but how many subspecies of tiger can be found in the world today? ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. QUESTION 5 Sumatran tigers are critically endangered, can -

Supplement - 2016

Green and black poison dart frog Supplement - 2016 Whitley Wildlife Conservation Trust Paignton Zoo Environmental Park, Living Coasts & Newquay Zoo Supplement - 2016 Index Summary Accounts 4 Figures At a Glance 6 Paignton Zoo Inventory 7 Living Coasts Inventory 21 Newquay Zoo Inventory 25 Scientific Research Projects, Publications and Presentations 35 Awards and Achievements 43 Our Zoo in Numbers 45 Whitley Wildlife Conservation Trust Paignton Zoo Environmental Park, Living Coasts & Newquay Zoo Bornean orang utan Paignton Zoo Inventory Pileated gibbon Paignton Zoo Inventory 1st January 2016 - 31st December 2016 Identification IUCN Status Arrivals Births Did not Other Departures Status Identification IUCN Status Arrivals Births Did not Other Departures Status Status 1/1/16 survive deaths 31/12/16 Status 1/1/16 survive deaths 31/12/16 >30 days >30 days after birth after birth MFU MFU MAMMALIA Callimiconidae Goeldi’s monkey Callimico goeldii VU 5 2 1 2 MONOTREMATA Tachyglossidae Callitrichidae Short-beaked echidna Tachyglossus aculeatus LC 1 1 Pygmy marmoset Callithrix pygmaea LC 5 4 1 DIPROTODONTIA Golden lion tamarin Leontopithecus rosalia EN 3 1 1 1 1 Macropodidae Pied tamarin Saguinus bicolor CR 7 3 3 3 4 Western grey Macropus fuliginosus LC 9 2 1 3 3 Cotton-topped Saguinus oedipus CR 3 3 kangaroo ocydromus tamarin AFROSORICIDA Emperor tamarin Saguinus imperator LC 3 2 1 subgrisescens Tenrecidae Cebidae Lesser hedgehog Echinops telfairi LC 8 4 4 tenrec Squirrel monkey Saimiri sciureus LC 5 5 Giant (tail-less) Tenrec ecaudatus LC 2 2 1 1 White-faced saki Pithecia pithecia LC 4 1 1 2 tenrec monkey CHIROPTERA Black howler monkey Alouatta caraya NT 2 2 1 1 2 Pteropodidae Brown spider monkey Ateles hybridus CR 4 1 3 Rodrigues fruit bat Pteropus rodricensis CR 10 3 7 Brown spider monkey Ateles spp.