Managing Online Communications and Feedback Relating to the Welsh Visitor Attraction Experience: Apathy and Inflexibility in Tourism Marketing Practice?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing Excellence in Wales / / / Capital Programme – 2016/17-2019/20

Constructing Excellence in Wales / / / Capital Programme – 2016/17-2019/20 Constructing Excellence in Wales Welsh Local Authorities CAPITAL PROGRAMME: 2016/17 – 2019/20 MARCH 2017 Constructing Excellence in Wales / / / Capital Programme – 2016/17-2019/20 Contents Page No. Introduction 2 Overview Annual Summary 3 Sector Summary 3 Regional Sector Summary 3-4 Local Authority Summary 5 Sector/Local Authority Annual Summary 6-9 2016/17, 2017/18, 2018/19, 2019/20 Regional Capital Programmes North Wales 10-22 Anglesey, Conwy, Denbighshire, Flintshire, Gwynedd, Wrexham Mid Wales 23-27 Ceredigion, Powys South East Wales 28-46 Blaenau Gwent, Bridgend, Caerphilly, Cardiff, Merthyr Tydfil, Monmouthshire, Newport, Rhondda Cynon Taf, Torfaen, Vale of Glamorgan South West Wales 47-56 Carmarthen, Neath Port Talbot, Pembrokeshire, Swansea Introduction This forward programme provides visibility to £3.5bn of local authority capital investment in Wales over the four years to 2019/20. The importance of the visibility of the forward pipeline of work was emphasised in the CEW ‘No Turning Back’ report in 2010 and in its 2015 review. Much has been achieved since the CEW pilot exercise began in autumn 2011, with regular updates now produced of :- the Wales Infrastructure Investment Plan (WIIP) pipeline (WG) the Welsh local authorities’ 4-year capital programme (CEW) a sector-based programme for the WIIP local authority projects (CEW) a Wales extract of the UK pipeline ( non-devolved ) (CEW) We continue to liaise with industry representatives as to how to improve the visibility of the future pipeline of work. The responses from the industry have overwhelmingly supported the continuation and development of the programme. -

The Dandie Dinmont Terrier

www.davesbits.couk INTRODUCTION Poet Lauriat I’ll never become But composing this book has been such fun So don’t criticise my effort at rhyme Which over the years has taken much time. It’s a memory of me for you to browse To pass away your leisure hours! SPRING WALK I leave the house to start on my round And take the path along the Oat Ground, Passed the field where the children are playing Being pushed on the swings gently swaying. I take the lane down to Holy Well See the hawthorn buds beginning to swell. Primroses bloom on the banks down this lane, ‘Neath the hedges cut by machine again. Little birds searching for somewhere to nest Keep checking to see which side is best. Left passed the ponies asleep in the sun And the chickens are scratching in their run. The blackthorn’s in flower, winter’s not over yet I hope its rain and not snow that we get. I follow this lane which runs by the stream Note the leaves on the willow turning green. Under the tunnel of overgrown trees Where the catkins are swaying in the breeze. An old yew tree leans where vegetables grow And roses are pruned for their summer show. Under two huge poplars which come into view Spring flowers form a carpet of yellow and blue. The path crosses the stream and goes on beyond Where the breeze causes ripples upon a pond. The cattle in the field are chewing the cud The coot’s on her nest and ducks in the mud. -

Wales & the Welsh Borders

Wales & the Welsh Borders A Journey Through the reserved Ancient Celtic Kingdom rights th th all September 10 - 19 2020 Wales, Castle ruins, meandering medieval streets, and a Visit magnificent Celtic heritage bring the beauty of Wales (2011) to life against a backdrop of rolling green hills and dramatic sea cliffs. Past and present coexist in this distinctive part of the world—the Romans mined for copyright gold, the Tudors founded a dynasty, and the Normans Crown built castles whose ancient remains are scattered along © windy hilltops throughout the countryside. Along the way, Wales’ ancient Celtic heritage was memorialized in a stunning collection of literature and artwork. From the magnificence of Caernarfon to the breathtaking vistas on peaceful St. David’s Peninsula, Harlech Castle we’ll explore the places, personalities, and sweep of history that constitute the haunting beauty of Wales. We’ll also step in and out of ancient market towns like Ludlow and Carmarthen, supposed birthplace of Merlin, located in “the garden of Wales” and visit beautiful villages like Hay-on-Wye, famous for its abundance of antique book stores, and ancient Shrewsbury, with more than 600 historic listed buildings and narrow medieval alleyways. We’ll experience the natural splendor of Snowdonia, with the highest mountain peaks in the country, and the Wye Valley, rich in ancient woodlands, wildlife, and the idyllic setting for the timelessly romantic ruins of Tintern Abbey. Join Discover Europe as we pay homage to great poets and storytellers and journey into the heart and history of ancient Wales. Let the magic of this The cost of this itinerary, per person, double occupancy is: Celtic kingdom come to life on Wales & the Welsh Land only (no airfare included): $4280 Borders. -

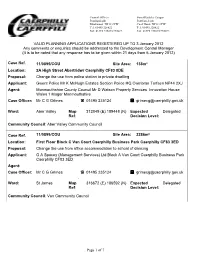

Page 1 of 7 VALID PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED UP

Council Offices Swyddfeydd y Cyngor Pontllanfraith Pontllan-fraith Blackwood NP12 2YW Coed Duon. NP12 2YW Tel: 01495 226622 Tel: 01495 226622 Fax: 01495 235013/235022 Fax: 01495 235013/235022 VALID PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED UP TO 3 January 2012 Any comments or enquiries should be addressed to the Development Control Manager (It is to be noted that any response has to be given within 21 days from 6 January 2012) Case Ref. 11/0895/COU Site Area: 138m² Location: 2A High Street Abertridwr Caerphilly CF83 8DE Proposal: Change the use from police station to private dwelling Applicant: Gwent Police Mr K McHugh Estates Section Police HQ Cwmbran Torfaen NP44 2XJ Agent: Monmouthshire County Council Mr D Watson Property Services Innovation House Wales 1 Magor Monmouthshire Case Officer: Mr C G Grimes 01495 235124 [email protected] 6 Ward: Aber Valley Map 312049 (E) 189448 (N) Expected Delegated Ref: Decision Level: Community Council: Aber Valley Community Council Case Ref. 11/0899/COU Site Area: 2286m² Location: First Floor Block C Van Court Caerphilly Business Park Caerphilly CF83 3ED Proposal: Change the use from office accommodation to school of dancing Applicant: GA Spacey (Management Services) Ltd Block A Van Court Caerphilly Business Park Caerphilly CF83 3ED Agent: Case Officer: Mr C G Grimes 01495 235124 [email protected] 6 Ward: St James Map 316672 (E) 186592 (N) Expected Delegated Ref: Decision Level: Community Council: Van Community Council Page 1 of 7 Case Ref. 11/0909/FULL Site Area: 2009m² Location: 5 Oak Tree Rise Homeleigh Newbridge Newport NP11 4RH Proposal: Erect a four bedroom family dwelling Applicant: Mr G Jones 5-9 Fern Close Penyfan Industrial Estate Crumlin Newport NP11 3EH Agent: Hurley & Davies Ltd Mr D Meek 1 Axis Court Riverside Business Park Swansea SA7 0AJ Case Officer: Mrs S Hockaday 01495 235163 [email protected] 6 Ward: Newbridge Map 320268 (E) 197029 (N) Expected Delegated Ref: Decision Level: Community Council: Not Applicable Case Ref. -

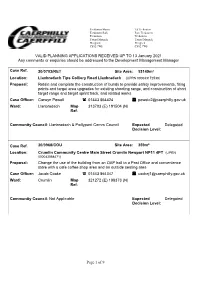

Page 1 of 9 VALID PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED up to 13 January 2021 Any Comments Or Enquiries Should Be Addressed to the Deve

Tredomen House Tŷ Tredomen Tredomen Park Parc Tredomen Tredomen Tredomen Ystrad Mynach Ystrad Mynach Hengoed Hengoed CF82 7WF CF82 7WF VALID PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED UP TO 13 January 2021 Any comments or enquiries should be addressed to the Development Management Manager Case Ref. 20/0703/RET Site Area: 53149m² Location: Llanbradach Tips Colliery Road Llanbradach (UPRN 000043172539) Proposal: Retain and complete the construction of bunds to provide safety improvements, firing points and target area upgrades for existing shooting range, and construction of short target range and target sprint track, and related works Case Officer: Carwyn Powell 01443 864424 [email protected] Ward: Llanbradach Map 313703 (E) 191504 (N) Ref: Community Council: Llanbradach & Pwllypant Comm Council Expected Delegated Decision Level: Case Ref. 20/0968/COU Site Area: 359m² Location: Crumlin Community Centre Main Street Crumlin Newport NP11 4PT (UPRN 000043068471) Proposal: Change the use of the building from an OAP hall to a Post Office and convenience store with a cafe coffee shop area and an outside seating area Case Officer: Jacob Cooke 01443 864347 [email protected] Ward: Crumlin Map 321272 (E) 198373 (N) Ref: Community Council: Not Applicable Expected Delegated Decision Level: Page 1 of 9 Case Ref. 20/1004/FULL Site Area: 339m² Location: 26 Heol Isaf Nelson Treharris CF46 6NS (UPRN 000043007925) Proposal: Erect single storey extension to rear and side of property Case Officer: Jacob Cooke 01443 864347 [email protected] -

County Borough of Caerphilly

November 2020 Summary Full report and maps: https://ldbc.gov.wales/ @LDBCW This document is available in Welsh County Borough of Caerphilly Summary of Final Recommendations Who we are : The Local Democracy and Boundary Commission for Wales is an independent Welsh Government Sponsored Body. It was established under the Local Democracy (Wales) Act 2013 with the main purpose of publishing a programme of work which keeps under review the electoral arrangements for the 22 principal councils. The Commission makes electoral review recommendations, which it feels are in the interest of effective and convenient local government. This review has been conducted as a result of the former Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Local Government’s Written Statement of 23 June 2016 as part of an all Wales review programme for the 2022 local government elections. © Crown copyright and database rights [2020] OS [100047875] Summary of our Recommendations: The Commission recommends a council of 69 members, a reduction from the present 73 members. The Commission recommends a change to the arrangement of electoral wards that will achieve a marked improvement in the level of electoral parity across the County Borough of Caerphilly. The Commission recommends 30 electoral wards, a reduction from 33 existing wards. The largest under-representation is recommended to be 24% above the proposed county average in Aberbargoed and Bargoed. The largest over-representation is recommended to be 20% below the proposed county average in Aber Valley. The Commission is recommending 25 multi-member wards consisting of 12 two- member electoral wards; 12 three-member electoral wards; and one four-member electoral ward. -

Charity Arts Auction Josef Herman Foundation

Charity Arts Auction Josef Herman Foundation Exhibition Auction Day 18th Nov - 6th Dec Sun 8th Dec The Welfare Hall Glynn Vivian Art Ystradgynlais Gallery Swansea Special evening viewing on Viewing from 11.30am Friday 22nd Nov at 7pm Auction starts at 1.30pm Auctioneer: Arfon Haines Davies Listings Josef Herman Foundation Lot 1: John Abell. “Adam & Eve” Lot 2: John Abell. “Cardiff Girls” Lot 5: Joan Baker. “Mouth of the Lot 6: Joan Baker. “Waterfall Cave” Temple Bay” A/P Limited edition lithographic print A/P Limited edition lithographic print of 20 on handmade paper. of 20 on handmade paper. Oil on canvas. Framed. Oil on canvas. Framed. 71.5 x 54 cms unframed. 74 x 54 cms unframed. (50.5 x 61 cms unframed). (54 x 45.5 cms unframed). Estimate: £250 - £350 Estimate: £250 - £350 Estimate: £200 Estimate: £200 Lot 3: Jacqueline Alkema. “Woman Lot 4: Jacqueline Alkema. “In the Lot 7: Joan Baker. “Caerphilly Lot 8: Joan Baker. “Witches Point” with Birds” night series II” Mountain” Oil on canvas. Framed. Oil on paper. 42 x 53 cms framed. Oil on paper. 45.5 x 53 cms framed. Oil on canvas. Framed. (61 x 76 cms unframed). (31 x 21 unframed). (29 x 20 unframed). (61 x 76 cms unframed). Estimate: £350 Estimate: £395 – £450 Estimate: £395 – £450 Estimate: £350 1 2 Listings Josef Herman Foundation Lot 9: Joan Baker. “Sun after Rain – Lot 10: Iwan Bala. “Ystad Bardd/ Lot 13: Seren Bell. “Welsh Mountain Lot 14: Gwenllian Beynon. “Llestri Merthyr Mawr” The Poet's Estate” Ewe & Lamb” Mam” Framed. -

THE OGWEN VALLEY MOUNTAIN RESCUE ORGANISATION 41St

THE OGWEN VALLEY MOUNTAIN RESCUE ORGANISATION 41st ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2005 Published by the Ogwen Valley Mountain Rescue Organisation Bryn Poeth, Capel Curig, Betws-y-Coed, Conwy LL24 0EU Edited by Dave and Jo Worrall © OVMRO 2006 Please note that the articles contained in the Annual Report express the views of the individuals and are not necessarily the views of the Team. Argraffwyd gan / Printed by: Gwasg Ffrancon Dol Dafydd, Bethesda, Gwynedd LL57 3LY 1 Contents Chairman’s Foreword 5 Team Leaders Report 9 Incident Report 13 Incident Narrative 15 Equipment Officer’s Report 25 Treasurer’s Report 27 Garage Appeal 30 Transport Officer’s Report 31 Training Officer’s Report 33 Press Officer’s Report 37 Ogwen on the Web 39 Garage Report 41 Casualty Care Report 43 333 Support Group - Chairman's Report 47 Location of Collection Boxes 46 Salutation to My Mother 49 Carole De Silva 52 40th Anniversary 53 Now to the case of the wrong Mountain and the 55 guide who disappeared! 2 Chairman’s Forward The OVMRO Team year is slowly drawing to a close and with it the 40th birthday anniversary for the Team. It has been a privilege and indeed an honour to be Chairman of the Team during this important landmark in its history. The anniversary has been celebrated by many events organised by a working group within the Team and 333 and thanks are due for their hard work. We began in March ’05 with the AGM and the annual dinner where we hosted some of the founding members of the Team as our guests. -

Cross-Curriculum Learning with Swansea Cultural Venues

1 CROSS-CURRICULUM LEARNING WITH SWANSEA CULTURAL VENUES Led by experienced artist-educators with specialist knowledge April 2018 – March 2019 2 Cross-Curriculum Learning Experience for Schools 4Site is a one stop cultural shop for all schools in Swansea. Check out the exciting range of work and the exhibitions going on at the Dylan Thomas Centre, the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea Museum, and West Glamorgan Archives. We recommend reading through this pack prior to your visit and if you have any further questions, please contact the appropriate venue. This document contains all the practical information you will need to organise your schools cultural education sessions and benefit from your 4site membership. Dylan Thomas Centre Glynn Vivian Art Gallery [email protected] [email protected] 01792 463980 01792 516900 Swansea Museum West Glamorgan Archives [email protected] [email protected] 01792 653763 01792 636589 3 CONTENTS 1. Introduction Page 4 2. Venues Page 5 - Map - Information 3. Fees and Charges Page 10 - How to pay 4. How to Book Page 11 - Booking forms - Group Sizes 5. Planning your visit Page 15 - Access - Parking - Resources 6. Session Programmes Page 18 - Foundation - Key Stage 2 - Key Stage 2 + 3 - Key Stage 4 7. Funding Support Page 27 “Excellent information on Glynn “A wonderful educational visit Vivian. Excellent hands on and @swanseamuseum. We have interactive workshop. Every thoroughly enjoyed our topic on opportunity taken to develop Ancient Egypt #Year1&2” pupils’ art skills: Sketching, observing, problem solving, Teacher, St Helen’s Catholic drawing.” Primary School Teacher, YGG Bryniago 4 1. -

Camrose Community Audit

Heartlands Hub Heritage and Natural Environment Audit Part B Camrose Community Audit For: PLANED May 2012 Heartlands Hub Heritage and Natural Environment Audit Part B Camrose Community Audit By Jenny Hall, MIfA & Paul Sambrook, MIfA Trysor Trysor Project No. 2011/230 For: PLANED May 2012 Cover photograph: Camrose Baptist Chapel, 2012 Heartlands Hub Heritage & Natural Resources Audit Camrose Community RHIF YR ADRODDIAD - REPORT NUMBER: Trysor 2011/230 DYDDIAD 4ydd Mai 2012 DATE 4th May 2012 Paratowyd yr adroddiad hwn gan bartneriad Trysor. Mae wedi ei gael yn gywir ac yn derbyn ein sêl bendith. This report was prepared by the Trysor partners. It has been checked and received our approval. JENNY HALL MIfA Jenny Hall PAUL SAMBROOK MIfA Paul Sambrook DYDDIAD DATE 04/05/2012 Croesawn unrhyw sylwadau ar gynnwys neu strwythur yr adroddiad hwn. We welcome any comments on the content or structure of this report. 38, New Road, Treclyn Gwaun-cae-Gurwen Eglywswrw Ammanford Crymych Carmarthenshire Pembrokeshire SA18 1UN SA41 3SU 01269 826397 01239 891470 www.trysor.net [email protected] CONTENTS 1. Community Overview 1 Landscape and Geology 1 2. Natural Heritage (Designatons and Attractions) 3 3. Heritage (Archaeology, History and Culture) 5 Heritage Overview 5 Designated Heritage Sites and Areas 9 List of Sites by Period 10 Cultural Sites 12 4. Interpretation 14 5. Tourism-Related Commerce 15 6. Observations 18 7. Camrose Heritage Gazetteer Index 20 8. Camrose Heritage Gazetteer 24 9. Camrose Culture Gazetteer 91 10. Camrose Natural Attractions Gazetteer 96 Camrose Heritage & Natural Resources Audit CAMROSE COMMUNITY 1. COMMUNITY OVERVIEW Camrose is a large, inland community, covering an area of 45.92km2, see Figure 1. -

Download Plas Power Woods Management

Plas Power Woods Plas Power Woods Management Plan 2013-2018 Plas Power Woods MANAGEMENT PLAN - CONTENTS PAGE ITEM Page No. Introduction Plan review and updating Woodland Management Approach Summary 1.0 Site details 2.0 Site description 2.1 Summary Description 2.2 Extended Description 3.0 Public access information 3.1 Getting there 3.2 Access / Walks 4.0 Long term policy 5.0 Key Features 5.1 Ancient Semi Natural Woodland 5.2 Planted Ancient Woodland Site 5.3 Informal Public Access 5.4 Historic Features 5.5 Semi Natural Open Ground Habitat 6.0 Work Programme Appendix 1: Compartment descriptions Appendix 2: Harvesting operations (20 years) Glossary MAPS Access Conservation Features Management 2 Plas Power Woods THE WOODLAND TRUST INTRODUCTION PLAN REVIEW AND UPDATING The Trust¶s corporate aims and management The information presented in this Management approach guide the management of all the plan is held in a database which is continuously Trust¶s properties, and are described on Page 4. being amended and updated on our website. These determine basic management policies Consequently this printed version may quickly and methods, which apply to all sites unless become out of date, particularly in relation to the specifically stated otherwise. Such policies planned work programme and on-going include free public access; keeping local people monitoring observations. informed of major proposed work; the retention Please either consult The Woodland Trust of old trees and dead wood; and a desire for website www.woodlandtrust.org.uk or contact the management to be as unobtrusive as possible. Woodland Trust The Trust also has available Policy Statements ([email protected]) to confirm covering a variety of woodland management details of the current management programme. -

10919 WTB Tourism English 108Pp

Cultural tourism strategy for Wales Brecon Jazz Eisteddfod Powis Castle Cardiff Bay Whilst every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in this publication, the Wales Tourist Board can accept no liability for any errors, inaccuracies or omissions for any matter in any way arising out of the publication of the information. Published by the Wales Tourist Board, Brunel House, 2 Fitzalan Road, Cardiff CF24 0UY ©2003 Designed by Peter Gill & Associates, Cardiff www.petergill.com CONTENTS Foreword 3 Executive Summary 4 1.0 Introduction 10 2.0 The Policy Context 12 3.0 The Market for Cultural Tourism 16 4.0 The Cultural Tourism Product 26 5.0 Strategic Principles and Vision 46 6.0 Strategy for Action 48 Thematic Programme 1 48 Thematic Programme 2 58 Thematic Programme 3 74 Thematic Programme 4 76 Action Plan 78 7.0 Implementation 90 8.0 Monitoring and Evaluation 92 Appendix 1 94 Appendix 2 96 Appendix 3 98 Appendix 4 104 1 F OREWORD The Wales Tourist Board recognises the vital role that our culture and the Welsh language places in differentiating Wales from our competitors so giving us that ‘competitive edge’.Whilst those who are defined as cultural tourists are a relatively small market, they are high value and projected to grow in numbers. Furthermore, cultural activities or experiences rarely fail to touch or enhance every visitor’s experience. This document sets out a strategic framework for action by both the Board and our partners to develop Wales’ potential as a cultural tourism destination. Our vision is for Wales to be recognised internationally as a destination offering a quality cultural tourism experience based on our unique culture which forms an essential part of the overall visitor experience.