Thirty Years Later: Enrichment Practices for Captive Mammals à Julia M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

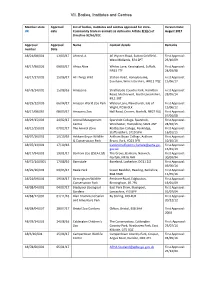

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

Managing Online Communications and Feedback Relating to the Welsh Visitor Attraction Experience: Apathy and Inflexibility in Tourism Marketing Practice?

Managing online communications and feedback relating to the Welsh visitor attraction experience: apathy and inflexibility in tourism marketing practice? David Huw Thomas, BA, PGCE, PGDIP, MPhil Supervised by: Prof Jill Venus, Dr Conny Matera-Rogers and Dr Nicola Palmer Submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the degree of PhD University of Wales Trinity Saint David. 2018 i ii DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for deposit in the University’s digital repository. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 iii iv Abstract Understanding of what constitutes a tourism experience has been the focus of increasing attention in academic literature in recent years. For tourism businesses operating in an ever more competitive marketplace, identifying and responding to the needs and wants of their customers, and understanding how the product or consumer experience is created is arguably essential. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 Presents the Findings of the Survey of Visits to Visitor Attractions Undertaken in England by Visitbritain

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VisitBritain would like to thank all representatives and operators in the attraction sector who provided information for the national survey on which this report is based. No part of this publication may be reproduced for commercial purp oses without previous written consent of VisitBritain. Extracts may be quoted if the source is acknowledged. Statistics in this report are given in good faith on the basis of information provided by proprietors of attractions. VisitBritain regrets it can not guarantee the accuracy of the information contained in this report nor accept responsibility for error or misrepresentation. Published by VisitBritain (incorporated under the 1969 Development of Tourism Act as the British Tourist Authority) © 2004 Bri tish Tourist Authority (trading as VisitBritain) Cover images © www.britainonview.com From left to right: Alnwick Castle, Legoland Windsor, Kent and East Sussex Railway, Royal Academy of Arts, Penshurst Place VisitBritain is grateful to English Heritage and the MLA for their financial support for the 2003 survey. ISBN 0 7095 8022 3 September 2004 VISITOR ATTR ACTION TRENDS ENGLAND 2003 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS A KEY FINDINGS 4 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 12 1.1 Research objectives 12 1.2 Survey method 13 1.3 Population, sample and response rate 13 1.4 Guide to the tables 15 2 ENGLAND VISIT TRENDS 2002 -2003 17 2.1 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by attraction category 17 2.2 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by admission type 18 2.3 England visit trends -

Review of Zoos' Conservation and Education Contribution

Review of Zoos’ Conservation and Education Contribution Contract No : CR 0407 Prepared for: Jane Withey and Margaret Finn Defra Biodiversity Programme Zoos Policy Temple Quay House Bristol BS1 6EB Prepared by: ADAS UK Ltd Policy Delivery Group Woodthorne Wergs Road Wolverhampton WV6 8TQ Date: April 2010 Issue status: Final Report 0936648 ADAS Review of Zoos’ Conservation and Education Contribution Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank in particular the zoos, aquariums and animal parks that took part in the fieldwork and case studies. We are also grateful to members of the Consultation Group and the Steering Group for their advice and support with this project. The support of Tom Adams, Animal Health, is also acknowledged for assistance with sample design. Project Team The ADAS team that worked on this study included: • Beechener, Sam • Llewellin, John • Lloyd, Sian • Morgan, Mair • Rees, Elwyn • Wheeler, Karen The team was supported by the following specialist advisers: • BIAZA (British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums); and • England Marketing - provision of telephone fieldwork services I declare that this report represents a true and accurate record of the results obtained/work carried out. 30 th April 2010 Sam Beechener and Mair Morgan (Authors’ signature) (Date) 30 th April 2010 John Llewellin (Verifier’s signature) (Date) Executive Summary Executive Summary Objectives The aims of this project were to collect and assess information about the amount and type of conservation and education work undertaken by zoos in England. On the basis of that assessment, and in the light of the Secretary of State’s Standards of Modern Zoo Practice (SSSMZP) and the Zoos Forum Handbook (2008 - including the Annexes to Chapter 2), the project will make recommendations for: • minimum standards for conservation and education in a variety of sizes of zoo; and • methods for zoo inspectors to enable them to assess zoo conservation and educational activities. -

LICENSING REGULATORY COMMITTEE (D) Agenda Item 7

Part One LICENSING REGULATORY COMMITTEE (D) Agenda Date of Meeting: 5th – 7th July 2016 Item 7 Reporting Officer: Principal Environmental Health Officer Title: Zoo Licensing Act 1981 (as amended) Zoo Licence for South Lakes Safari Zoo Ltd Compliance Report Regarding Current Licensing Conditions Summary & Purpose of the Report Mr David Stanley Gill holds a zoo licence issued on 8th June 2010 to operate a zoo at premises known as South Lakes Safari Zoo Ltd, Crossgates, Dalton-in-Furness, Cumbria, LA15 8JR. At a meeting of this Committee on 23rd / 24th February and 2nd March 2016 Members placed a number of conditions on the premises’ Zoo Licence. A special inspection was carried out at the Zoo on 23rd, 24th and 25th May 2016 to assess the Zoo’s progress towards compliance with licence conditions. This report details the finding of that inspection and makes recommendations to Members in relation to conditions that have been complied with, and those where compliance hasn’t been demonstrated. Background Information Mr David Stanley Gill holds a zoo licence issued on 8th June 2010 to operate a zoo at premises known as South Lakes Safari Zoo Ltd, Crossgates, Dalton-in-Furness, Cumbria, LA15 8JR. A special inspection was undertaken at the Zoo on 23th/24th and 25th May 2016 to check compliance with a number of conditions placed on the zoo licence at a Committee Meeting held on 23/24th February and 2nd March 2016. The inspectors undertaking the inspection were:- The Secretary of State Inspectors: Page 1 of 65 Professor Anna Meredith; MA VetMB PhD CertLAS DZooMed DipECZM MRCVS Nick Jackson MBE, Director of the Welsh Mountain Zoo. -

An Evaluation of Conservation by UK Zoos RESULTS

ANIMAL ARK OR SINKINGAn evaluation of SHIP? conservation by UK zoos Photo © Dr Joseph Tobias, University of Oxford Photo © Charles Smith, United States Fish and Wildlife Service July 2007 At least 5,624 species of vertebrate animals are Annual Reports, published accounts and animal threatened with extinction worldwide1. inventories5; BIAZA6 published data; data on Humankind’s contribution to the rapid loss of the European Co-operative Breeding Programmes (EEPs earth’s flora and fauna is now a widely & ESPs7) from EAZA8; ICM Research public opinion acknowledged phenomenon. To date, 190 survey (May 2007)9. countries have pledged to make a concerted effort to conserve the world’s threatened species Full details are available in Born Free reports: Is the by signing up to the Convention on Biological Ark Afloat? Captivity and Ex Situ Conservation in UK Diversity. Zoos (2007) and Committed to Conservation? An Overview of the Consortium of Charitable Zoos’ In The involvement of zoos in the conservation of Situ Conservation Dividend (2007). Both reports biodiversity, and specifically ex situ conservation2, available at www.bornfree.org.uk/zoocon became a legal obligation in Europe in 2002 with the implementation of the European Zoos Directive. The Directive was fully incorporated into UK zoo The IUCN Red List of Threatened legislation in 2003. Perhaps recognising an SpeciesTM compared to species in the CCZ opportunity to refute growing scepticism over the The IUCN Red List catalogues and highlights those keeping of animals in captivity, zoos assumed the taxa facing a higher risk of global extinction. In this role of animal ‘arks’ and promoted their new review, the Red List status for all mammal, bird and conservation purpose. -

ANIMAL CARE Welcome to the Level 2 Diploma in Animal Care at Cronton Sixth Form College

ANIMAL CARE Welcome to the Level 2 Diploma in Animal Care at Cronton Sixth Form College. We are really looking forward to seeing you at enrolment and starting the course with us in September. The team have put together a range of learning materials to spur you into action and prepare you for the exciting times ahead! Your programme of study will cover the following units: Work Experience Animal Feeding and Accommodation Animal Health and Welfare Care of Exotics Animal Handling and Behaviour Animal Biology UPCOMING TRIPS Chester Zoo Knowsley Safari Park Acorn Farm Blackpool Zoo Dogs Trust If you have any questions about enrolment then please speak to the schools liaison team by emailing [email protected] If you have any questions about studying Animal Care then please contact Adam Howson at [email protected] Topic 1: Work Experience in the Animal Care Together we will help you gain the skills to find your dream job. Try to think of as many jobs in animal care as you can? One of your Classmates wants to be an RSPCA inspector – can you find out how much they will expect to earn per year? £____________ Can you think of 10 key skills an RSPCA inspector would need in their job? 1 Animal 2 Care 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Topic 2: Animal Health down at the Zoo Molly the vet has asked for your help. The four tigers are due their annual vaccination. Can you help her work out the correct dosage based on how much they weigh? The recommended dose is worked out as 0.15ml/Kg. -

UK-First-Breeding-Register.Pdf

INTRODUCTION TO EDITION The original author and compiler of this record, Dave Coles has devoted a great deal of his time in creating a unique reference document which I am privileged to continue working with. By its very nature the document in a living project which will continue to grow and evolve and I can only hope and wish that I have the dedication as Dave has had in ensuring the continuity of the “First Breeding Register”. Initially all my additions and edits will be indicated in italics though this will not be used in the main body of the record (when a new record is added). Simon Matthews (2011) It is over eighty years since Emilius Hopkinson collated his RECORDS OF BIRDS BRED IN CAPTIVITY, which formed the starting point for my attempt at recording first breeding records for the UK. Since the first edition of my records was published in 1986, classification has changed several times and the present edition incorporates this up-dated classification as well as first breeding recorded since then. The research needed to produce the original volume took many years to complete and covered most avicultural literature. Since that time numerous people have kept me abreast of further breedings and pointing out those that have slipped the net. This has hopefully enabled the records to be kept up-to- date. To those I would express my thanks as indeed I do to all that have cast their eyes over the new list and passed comments, especially the ever helpful Reuben Girling who continues to pass on enquiries. -

Population and Habitat Viability Assessment the Stakeholder Workshop

Butler’s Gartersnake (Thamnophis butleri) in Wisconsin: Population and Habitat Viability Assessment The Stakeholder Workshop 5 – 8 February, 2007 Milwaukee County, Wisconsin Workshop Design and Facilitation: IUCN / SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group Workshop Organization: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of Endangered Resources WORKSHOP REPORT Photos courtesy of Wisconsin Bureau of Endangered Resources. A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, in collaboration with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources / Bureau of Endangered Resources. Hyde, T., R. Paloski, R. Hay, and P. Miller (eds.) 2007. Butler’s Gartersnake (Thamnophis butleri) in Wisconsin: Population and Habitat Viability Assessment – The Stakeholder Workshop Report. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, Apple Valley, MN. IUCN encourage meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believe that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report reflect the issues discussed and ideas expressed by the participants in the workshop and do not necessarily reflect the formal policies IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. © Copyright CBSG 2007 Additional copies of Butler’s Gartersnake (Thamnophis butleri) in Wisconsin: Population and Habitat Viability Assessment – The Stakeholder Workshop Report can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist -

CPSG Donors $25,000 and Above $20,000 and Above $15,000 and Above *

CPSG Donors $25,000 and above $20,000 and above $15,000 and above * Karen Dixon & Nan Schaffer George Rabb * $10,000 and above* Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo Everland Zoological Gardens Tokyo Zoological Park Society Alice Andrews Fota Wildlife Park, Ireland Friends of the Rosamond Topeka Zoo Auckland Zoological Park Fundación Parques Gifford Zoo Wellington Zoo Anne Baker & Robert Reunidos Jacksonville Zoo & Gardens Zoo de la Palmyre Lacy Givskud Zoo Little Rock Zoo Dallas World Aquarium* Gladys Porter Zoo Los Angeles Zoo $250 and above Detroit Zoological Society Japanese Association of Prudence Perry African Safari, France Houston Zoo* Zoos & Aquariums (JAZA) Perth Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert San Diego Zoo Global Kansas City Zoo Philadelphia Zoo Museum Toronto Zoo Nancy & Peter Killilea Phoenix Zoo Lee Richardson Zoo Wildlife Conservation Laurie Bingaman Lackey Ed & Marie Plotka Lion Country Safari Society Linda Malek Riverbanks Zoo & Garden Roger Williams Park Zoo Zoo Leipzig* Milwaukee County Zoo Rotterdam Zoo Rolling Hills Wildlife Adventure Nordens Ark San Antonio Zoo Sacramento Zoo $5,000 and above North Carolina Zoological Taipei Zoo Steinhart Aquarium Al Ain Wildlife Park & Park Thrigby Hall Wildlife Jacqueline & Nick Vlietstra Resort Oregon Zoo Gardens Zoo Heidelberg Association of Zoos & Paignton Zoo Toledo Zoo Aquariums (AZA) Royal Zoological Society of Wassenaar Wildlife Breeding $100 and above British and Irish Antwerp Centre Ann Delgehausen Association of Zoos and Royal Zoological Society of White Oak Conservation Steven J. Olson