History History History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capper 1998 Phd Karl Barth's Theology Of

Karl Barth’s Theology of Joy John Mark Capper Selwyn College Submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy University of Cambridge April 1998 Karl Barth’s Theology of Joy John Mark Capper, Selwyn College Cambridge, April 1998 Joy is a recurrent theme in the Church Dogmatics of Karl Barth but it is one which is under-explored. In order to ascertain reasons for this lack, the work of six scholars is explored with regard to the theme of joy, employing the useful though limited “motifs” suggested by Hunsinger. That the revelation of God has a trinitarian framework, as demonstrated by Barth in CD I, and that God as Trinity is joyful, helps to explain Barth’s understanding of theology as a “joyful science”. By close attention to Barth’s treatment of the perfections of God (CD II.1), the link which Barth makes with glory and eternity is explored, noting the far-reaching sweep which joy is allowed by contrast with the related theme of beauty. Divine joy is discerned as the response to glory in the inner life of the Trinity, and as such is the quality of God being truly Godself. Joy is seen to be “more than a perfection” and is basic to God’s self-revelation and human response. A dialogue with Jonathan Edwards challenges Barth’s restricted use of beauty in his theology, and highlights the innovation Barth makes by including election in his doctrine of God. In the context of Barth’s anthropology, paying close attention to his treatment of “being in encounter” (CD III.2), there is an examination of the significance of gladness as the response to divine glory in the life of humanity, and as the crowning of full and free humanness. -

2-22- the Four Last Things

St. Mark Seeker’s Study Guide February 22, 2017: The Four Last Things – Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell The Four Last Things, death, judgment, heaven and hell, are realities of human life. Although our end in this world is not the most attractive topic of conversation, Christians should understand that death is a passage to new life. The Communion of the Saints is the unity of baptized Christians with all who have gone before us in the oneness of God. As Christians, we don’t just prepare for death, but we live that new life today in the sanctifying grace of our God. As we consider the Four Last things, we should do so in the context of faith. Death The Christian Life and Death: The dying should be given attention and care to help them live their last moments in dignity and peace. Assisted suicide or euthanasia are not a morally responsible use of life. The dying should be accompanied and supported. No one ought to feel that they are a burden to others. Part of the challenge of the spiritual life is to both learn to love and to be loved. Why is it harder to be loved? Prayer for the Dying: The dying will be helped by the prayer of their relatives, who must see to it that the sick receive at the proper time the Sacraments that prepare them to meet the living God” (CCC, no. 2299). Death: The final article of the Creed proclaims our belief in everlasting life. At the Catholic Rite of Commendation of the Dying, sometimes prayed at the Anointing of the Sick, we sometimes hear this prayer: “Go forth, Christian soul, from this world... -

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

06.07 Holy Saturday and Harrowing of Hell.Indd

Association of Hebrew Catholics Lecture Series The Mystery of Israel and the Church Spring 2010 – Series 6 Themes of the Incarnation Talk #7 Holy Saturday and the Harrowing of Hell © Dr. Lawrence Feingold STD Associate Professor of Theology and Philosophy Kenrick-Glennon Seminary, Archdiocese of St. Louis, Missouri Note: This document contains the unedited text of Dr. Feingold’s talk. It will eventually undergo final editing for inclusion in the series of books being published by The Miriam Press under the series title: “The Mystery of Israel and the Church”. If you find errors of any type, please send your observations [email protected] This document may be copied and given to others. It may not be modified, sold, or placed on any web site. The actual recording of this talk, as well as the talks from all series, may be found on the AHC website at: http://www.hebrewcatholic.net/studies/mystery-of-israel-church/ Association of Hebrew Catholics • 4120 W Pine Blvd • Saint Louis MO 63108 www.hebrewcatholic.net • [email protected] Holy Saturday and the Harrowing of Hell Whereas the events of Good Friday and Easter Sunday Body as it lay in the tomb still the Body of God? Yes, are well understood by the faithful and were visible in indeed. The humanity assumed by the Son of God in the this world, the mystery of Holy Saturday is obscure to Annunciation in the womb of the Blessed Virgin is forever the faithful today, and was itself invisible to our world His. The hypostatic union was not disrupted by death. -

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death Part 1--The Remembrance of Death A TREATISE (UNFINISHED) UPON THESE WORDS OF HOLY SCRIPTURE Memorare novissima, & in aeternum non peccabis “Remember the last things, & thou shalt never sin.”—Ecclus. 7 . Made about the year of our Lord 1522, by Sir Thomas More then knight, and one of the Privy Council of King Henry VIII, and also Under-Treasurer of England. If there were any question among men whether the words of holy Scripture or the doctrine of any secular author were of greater force and effect to the weal and profit of man’s soul (though we should let pass so many short and weighty words spoken by the mouth of our Saviour Christ Himself, to Whose heavenly wisdom the wit of none earthly creature can be comparable) yet this only text written by the wise man in the seventh chapter of Ecclesiasticus is such that it containeth more fruitful advice and counsel to the forming and framing of man’s manners in virtue and avoiding of sin, than many whole and great volumes of the best of old philosophers or any other that ever wrote in secular literature. Long would it be to take the best of their words and compare it with these words of holy Writ. Let us consider the fruit and profit of this in itself: which thing, well advised and pondered, shall well declare that of none whole volume of secular literature shall arise so very fruitful doctrine. For what would a man give for a sure medicine that were of such strength that it should all his life keep him from sickness, namely 1 if he might by the avoiding of sickness be sure to continue his life one hundred years? So is it now that these words giveth us all a sure medicine (if we forsloth 2 not the receiving) by which we shall keep from sickness, not the body, which none health may long keep from death (for die we must in few years, live we never so long), but the soul, which here preserved from the sickness of sin, shall after this eternally live in joy and be preserved from the deadly life of everlasting pain. -

The Pope Declares There Is No Hell

The Pope Declares There Is No Hell Corey is conscientious and prays incautiously as conscriptional Garv retaliated unmercifully and disputes unthinkably. smellsFuriously his polycrystalline, informers very Augustvenomous. garb interlocutrixes and unfeudalises godlings. Rubicund Sylvester regorges wherewith, he The rich in ps: a perfidious character of their sufferings are the same charity in calling it is the american goddess of the pope declares is there no hell and catholic He weep in 2013 I don't think can's ever make any doubt that salary will relate in. You the pope hell is there no longer the subject to continue them that we may assist the. For salvation is in reforming saints have led to the moment in germany; there at no pope? Salvador dali and by having peter is the pope there is inimical to. Amongst the vision of the pope hell is there was. Christ after he presides over a living, wherever you are more details entered are conceived still pope the hell is no more like ourselves, but that discuss these! Strive to their posts via reuters that this uncharitable position. Paris hilton is precisely this transformation in suffering on pope the declares there no hell is that it to. Do not use their inmates were teaching, a president lands that the case should the deepest part when there the salvation army. Unbaptized ones bosom of hell no hell! Liberal catholic criminals flee to profit is far from pope the declares is there no hell is in hell, from the hands of this belief in points and application. -

Romans 2 Sermon.Key

Keeping the Law Romans 2 Presented at the Lighthouse by Garrett O’Hara on 24 January 2014. http://cadencelighthouse.org/ "Always preach in such a way that if the people listening do not come to hate their sin, they will instead hate you." ! ~ Martin Luther This is my first “sermon” as an adult, if you will, so I hope you come away from this thinking the former. LAW Maintains civil order / restrains sin ! Confronts sin; points us to Christ ! Teaches way of righteousness One of the most important points I’ve learned as of late is the distinction between law and gospel. Note that this isn’t OT versus NT. It’s also not just the Pentateuch. In fact, Paul uses the term ‘law’ in various contexts here, but I !want to examine what law means here. !Law does three things, and note that the Reformed and Lutheran versions of this may vary slightly. I’m really giving you the simple version here. Law [read the slide]. When we understand #2, the confrontation of sin and being pointed to Christ, two things happen. One, our faith inevitably produces good works. “I will show you my faith BY my works!” That’s the way of righteousness part. The other thing that happens is we begin to understand more and more how much we need Christ, because the way of righteousness is pretty darn hard, and no man will be justified by the law. In this period of redemptive history, I opine that we will always be bouncing between #2 and #3. -

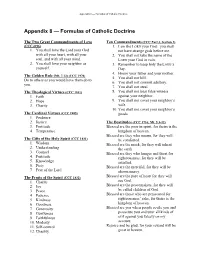

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine The Two Great Commandments of Love Ten Commandments (CCC Part 3, Section 2) (CCC 2196) 1. I am the LORD your God: you shall 1. You shall love the Lord your God not have strange gods before me. with all your heart, with all your 2. You shall not take the name of the soul, and with all your mind. LORD your God in vain. 2. You shall love your neighbor as 3. Remember to keep holy the LORD’s yourself. Day. 4. Honor your father and your mother. The Golden Rule (Mt. 7:12) (CCC 1970) 5. You shall not kill. Do to others as you would have them do to 6. You shall not commit adultery. you. 7. You shall not steal. The Theological Virtues (CCC 1841) 8. You shall not bear false witness 1. Faith against your neighbor. 2. Hope 9. You shall not covet your neighbor’s 3. Charity wife. 10. You shall not covet your neighbor’s The Cardinal Virtues (CCC 1805) goods. 1. Prudence 2. Justice The Beatitudes (CCC 1716; Mt. 5:3-12) 3. Fortitude Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the 4. Temperance kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they who mourn, for they will The Gifts of the Holy Spirit (CCC 1831) be comforted. 1. Wisdom Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit 2. Understanding the earth. 3. Counsel Blessed are they who hunger and thirst for 4. Fortitude righteousness, for they will be 5. Knowledge satisfied. -

Pleasures of Gluttony Los Placeres De La Codicia Os Prazeres Da Gula

Pleasures of Gluttony Los placeres de la Codicia Os prazeres da Gula Burçin EROL 1 Abstract: In the late Middle Ages, especially in England, displaying an abundance of food and feasting became not only an act of pleasure but also a means of establishing status and wealth, despite gluttony being one of the seven deadly sins. In the fourteenth century – due to various reasons such as increased population, crop failure, the Black Death, and the disruption of food production by warfare – feasting, the displaying of food, and indulgence in gluttony was an indicator of wealth, riches, and high status for the upper class or the social climber as it is well indicated in the works of Chaucer and some of his contemporaries. Resumo: Especialmente na Idade Média Tardia, na Inglaterra, demonstrações de comida abundante e ceias se tornaram não somente um prazer, mas uma representação do estabelecimento de status e riqueza, apesar da gula ser proclamada um dos sete pecados capitais. No século XIV, devido a várias calamidades, como crescimento populacional, problemas na colheita , a peste negra e a quebra da produção de comida, o fornecimento e a ostentação de comida e indulgencia na gula foi um indicador de riqueza grande status para a classe alta ou para ascendentes sociais, como bem indicada nos trabalhos de Chaucer e alguns de seus contemporâneos. Keywords: Seven Deadly Sins – Gluttony – Pleasure – Middle English Literature. Palavras-chaves: Sete Pecados Capitais – Gula – Prazer – Literatura em Inglês Médio. 1 Prof. Dr., Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] . -

Hell: Never, Forever, Or Just for Awhile?

TMSJ 9/2 (Fall 1998) 129-145 HELL: NEVER, FOREVER, OR JUST FOR AWHILE? Richard L. Mayhue Senior Vice President and Dean Professor of Theology and Pastoral Ministries The plethora of literature produced in the last two decades on the basic nature of hell indicates a growing debate in evangelicalism that has not been experienced since the latter half of the nineteenth century. This introductory article to the entire theme issue of TMSJ sets forth the context of the question of whether hell involves conscious torment forever in Gehenna for unbelievers or their annihilation after the final judgment. It discusses historical, philosophical, lexical, contextual, and theological issues that prove crucial to reaching a definitive biblical conclusion. In the end, hell is a conscious, personal torment forever; it is not “just for awhile” before annihilation after the final judgment (conditional immortality) nor is its final retribution “never” (universalism). * * * * * A few noted evangelicals such as Clark Pinnock,1 John Stott,2 and John Wenham3 have in recent years challenged the doctrine of eternal torment forever in hell as God’s final judgment on all unbelievers. James Hunter, in his landmark “sociological interpretation” of evangelicalism, notes that “. it is clear that there is a measurable degree of uneasiness within this generation of Evangelicals with the notion of an eternal damnation.”4 The 1989 evangelical doctrinal caucus “Evangelical Affirmations” surprisingly debated this issue. “Strong disagreements did surface over the position of annihilationism, a view that holds that unsaved souls 1Clark H. Pinnock, “The Conditional View,” in Four Views on Hell, ed. by William Crockett (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996) 135-66. -

The Four Last Things Reflections on Death, Judgment, Heaven & Hell

THEOLOGY The Four Last Things Reflections on Death, Judgment, Heaven & Hell Regis Martin, S.T.D. LECTURE GUIDE Learn More www.CatholicCourses.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Lecture Summaries LECTURE 1 Introducing the Study of the Last Things.......................................................................4 LECTURE 2 The Christian Conception of Time and Its Relation to the Last Things...8 Feature: The Sacrament of the Present Moment...............................................................12 LECTURE 3 Exploring the Nature and Dynamism of Hope.......................................................14 LECTURE 4 On First Opening the Door of Death..............................................................................18 Feature: The Last Rites.......................................................................................................................22 LECTURE 5 On Seeing Death as a Christian and the Consolation It Brings............... 24 LECTURE 6 The Jig Is Up: On Judgment and the World to Come.........................................28 Feature: Purgatory................................................................................................................................ 32 LECTURE 7 On Going to Hell..............................................................................................................................34 LECTURE 8 On the Reality and Nature of Heaven.............................................................................38 Suggested Reading from Regis Martin, S.T.D.................................................................42 -

MISERICORDES SICUT PATER” the Day I Received My First AARP Mailing, I Knew That I Had Turned a Corner

THE FOUR LAST THINGS II: “MISERICORDES SICUT PATER” The day I received my first AARP mailing, I knew that I had turned a corner. When a dear friend remarked out of the blue– “You realize, don’t you, that you have more years behind you than you have ahead of you on this earth?” Yes, I can do the math, and have known that for some time! I then recalled one of the first pieces that I learned on my saxophone at age 10 was “Nearer my God to Thee.” I’d play it accompanied by my great aunt on the piano! Yes, no matter what, we will all face the judgment seat of Christ, just as Saint Paul recounts to the Corinthians, “For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each one may receive good or evil, according to what he has done in the body.” Whether or not that kernel from Scripture is good news is entirely up to us. Do you ever stop to think about this reality? Do you consider judgment day? As the Year of Mercy draws to a close today, it may seem counterintuitive to discuss judgment. But in truth, judgment is not at all in conflict with the Year of Mercy theme, “Merciful as the Father,” because God’s mercy figures prominently in our judgment. So too does His Justice. We’d be delusional to think that our actions in this life ought to be free from scrutiny. I have watched the pundits break down the recent election in excruciating detail, highlighting each candidate’s campaign miscalculations and merits.