The World Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capper 1998 Phd Karl Barth's Theology Of

Karl Barth’s Theology of Joy John Mark Capper Selwyn College Submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy University of Cambridge April 1998 Karl Barth’s Theology of Joy John Mark Capper, Selwyn College Cambridge, April 1998 Joy is a recurrent theme in the Church Dogmatics of Karl Barth but it is one which is under-explored. In order to ascertain reasons for this lack, the work of six scholars is explored with regard to the theme of joy, employing the useful though limited “motifs” suggested by Hunsinger. That the revelation of God has a trinitarian framework, as demonstrated by Barth in CD I, and that God as Trinity is joyful, helps to explain Barth’s understanding of theology as a “joyful science”. By close attention to Barth’s treatment of the perfections of God (CD II.1), the link which Barth makes with glory and eternity is explored, noting the far-reaching sweep which joy is allowed by contrast with the related theme of beauty. Divine joy is discerned as the response to glory in the inner life of the Trinity, and as such is the quality of God being truly Godself. Joy is seen to be “more than a perfection” and is basic to God’s self-revelation and human response. A dialogue with Jonathan Edwards challenges Barth’s restricted use of beauty in his theology, and highlights the innovation Barth makes by including election in his doctrine of God. In the context of Barth’s anthropology, paying close attention to his treatment of “being in encounter” (CD III.2), there is an examination of the significance of gladness as the response to divine glory in the life of humanity, and as the crowning of full and free humanness. -

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

Religion–State Relations

Religion–State Relations International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 8 Religion–State Relations International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 8 Dawood Ahmed © 2017 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) Second edition First published in 2014 by International IDEA International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/> International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Telephone: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <http://www.idea.int> Cover design: International IDEA Cover illustration: © 123RF, <http://www.123rf.com> Produced using Booktype: <https://booktype.pro> ISBN: 978-91-7671-113-2 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 Advantages and risks ............................................................................................... -

Romans 2 Sermon.Key

Keeping the Law Romans 2 Presented at the Lighthouse by Garrett O’Hara on 24 January 2014. http://cadencelighthouse.org/ "Always preach in such a way that if the people listening do not come to hate their sin, they will instead hate you." ! ~ Martin Luther This is my first “sermon” as an adult, if you will, so I hope you come away from this thinking the former. LAW Maintains civil order / restrains sin ! Confronts sin; points us to Christ ! Teaches way of righteousness One of the most important points I’ve learned as of late is the distinction between law and gospel. Note that this isn’t OT versus NT. It’s also not just the Pentateuch. In fact, Paul uses the term ‘law’ in various contexts here, but I !want to examine what law means here. !Law does three things, and note that the Reformed and Lutheran versions of this may vary slightly. I’m really giving you the simple version here. Law [read the slide]. When we understand #2, the confrontation of sin and being pointed to Christ, two things happen. One, our faith inevitably produces good works. “I will show you my faith BY my works!” That’s the way of righteousness part. The other thing that happens is we begin to understand more and more how much we need Christ, because the way of righteousness is pretty darn hard, and no man will be justified by the law. In this period of redemptive history, I opine that we will always be bouncing between #2 and #3. -

The Case of Albania During the Enver Hoxha Era

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 40 Issue 6 Article 8 8-2020 State-Sponsored Atheism: The Case of Albania during the Enver Hoxha Era İbrahim Karataş Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Eastern European Studies Commons, Policy History, Theory, and Methods Commons, Religion Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation Karataş, İbrahim (2020) "State-Sponsored Atheism: The Case of Albania during the Enver Hoxha Era," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 40 : Iss. 6 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol40/iss6/8 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATE-SPONSORED ATHEISM: THE CASE OF ALBANIA DURING THE ENVER HOXHA ERA By İbrahim Karataş İbrahim Karataş graduated from the Department of International Relations at the Middle East Technical University in Ankara in 2001. He took his master’s degree from the Istanbul Sababattin Zaim University in the Political Science and International Relations Department in 2017. He subsequently finished his Ph.D. program from the same department and the same university in 2020. Karataş also worked in an aviation company before switching to academia. He is also a professional journalist in Turkey. His areas of study are the Middle East, security, and migration. ORCID: 0000-0002-2125-1840. -

Building Moderate Muslim Networks

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Center for Middle East Public Policy View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Building Moderate Muslim Networks Angel Rabasa Cheryl Benard Lowell H. Schwartz Peter Sickle Sponsored by the Smith Richardson Foundation CENTER FOR MIDDLE EAST PUBLIC POLICY The research described in this report was sponsored by the Smith Richardson Foundation and was conducted under the auspices of the RAND Center for Middle East Public Policy. -

Religious Repression in Tibet: Special Report 2012

Religious Repression in Tibet: Special Report 2012 UPRISING IN TIBET 2008 Documentation of protests in Tibet zôh-ˆÛ-ºIô-z-¤ÛºÛ-fôz-fP-hP-¤P-G®ô-ºwï¾-MÅ-¿eï-GmÅ-DP-ü Tibetan Centre for Human Rights & Democracy Buddhism too recognises that human beings are entitled to dignity, that all members of the human family have an equal and inalienable right to liberty, not just in terms of political freedom, but also at the funda- mental level of freedom from fear and want. Irrespective of whether we are rich or poor, educated or uneducated, belonging to one nation or another, to one religion or another, adhering to this ideology or that, each of us is just a human being like everyone else. ~ His Holiness the IVth Dalai Lama Contents I Introduction ....................................................................... 1 II A Brief History of Buddhism in Tibet ................................. 5 III Overview of Legal Framework Relating to the Freedom of Religion ....................................................................... 9 A. A General Look at the International Standards Protecting the Right to Freedom of Religion ........................................ 9 B. Chinese Law Relevant to Freedom of Religion .................. 11 1. International Obligations ............................................. 12 2. Constitution ................................................................. 13 3. Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure Law ................ 15 4. The State Secrets Law: the Regulation on State Secrets and the Specific Scope of Each Level -

Religion and Tolerance

2 199 8 Religion and tolerance Figure 8 Come, come, whoever you are; Wanderer, idolater, worshipper of fire; Come, even though you have broken your vows a thousand times; Come, and come yet again; Ours is not a caravan of despair. Mevlana Jelaluddin Rumi, 13th century 8.1 Introduction Do you realise how deeply religion(s) affect(s) your life? All around you, whether you are a believer or not, you can see the signs of religions. You may hear a call for prayer from the minaret of a mosque or church bells. When your friends get married, you might go to a synagogue or a church, or just attend a ceremony in the city hall. Every year you may decorate a pine tree at home and celebrate Christmas, or you might buy egg-shaped chocolates for Easter. For religious festivals, you may buy new clothes and visit your relatives or elderly neighbours, or give gifts to children. At a funeral, you hear prayers. No matter where you live in relation to the Mediterranean, religion plays an important role in your society, whether you are religious or not. Themes 200 In European and Mediterranean societies, there have always been different religions and religious diversity, around which there is a complex mixture of facts and myths, truths and misconceptions. On the one hand, religions bring people together: in principle, they constitute spaces for living, for practising the more noble qualities of human beings such as humanism, solidarity and compassion, by bringing together humanity’s efforts for a better shared future. On the other hand, history shows that religions have also been used or misused to justify painful conflicts and wars, persecutions and intolerance in the name of God, which have ultimately divided people rather than bringing them together. -

Religion & Politics

Religion & Politics New Developments Worldwide Edited by Roy C. Amore Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Religion and Politics Religion and Politics: New Developments Worldwide Special Issue Editor Roy C. Amore MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Roy C. Amore University of Windsor Canada Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/politics) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-429-7 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-430-3 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Roy C. Amore. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Preface to ”Religion and Politics: New Developments Worldwide” ................ ix Yashasvini Rajeshwar and Roy C. Amore Coming Home (Ghar Wapsi) and Going Away: Politics and the Mass Conversion Controversy in India Reprinted from: Religions 2019, 10, 313, doi:10.3390/rel10050313 .................. -

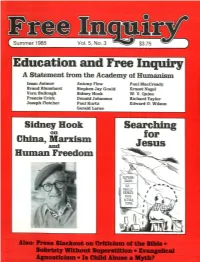

Education and Free Inquiry a Statement from the Academy of Humanism

Education and Free Inquiry A Statement from the Academy of Humanism Isaac Asimov Antony Flew Paul MacCready Brand Blanshard Stephen Jay Gould Ernest Nagel Vern Bullough Sidney Hook W. V. Quine Francis Crick Donald Johanson Richard Taylor Joseph Fletcher Paul Kurtz Edward O. Wilson Gerald Larue Sidney Hook Searching China, iIîarxism for and Jesus Human Freedom COMING SOON: TRE. REALLY REALLY T RUE ACTUAL TOMB 0 Also: Press Blackout on Criticism of the Bible • Sobriety Without Superstition • Evangelic Agnosticism • Is Child Abuse a Myth? SUMMER 1985, VOL. 5, NO. 3 ISSN 0272-0701 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 4 Education and Free Inquiry, A Statement From the Academy of Humanism 5 EDITORIALS 8 ON THE BARRICADES ARTICLES J ESUS IN HISTORY AND MYTH 10 Finding a Common Ground Between Believers and Unbelievers Paul Kurtz 13 Render to Jesus the Things that Are Jesus' Robert S. Alley 18 Jesus in Time and Space Gerald A. Larue 23 Biblical Scorecard: Was Jesus "Pro-Family") Thomas Franczyk 24 An Interview with Sidney Hook on China, Marxism, and Human Freedom 34 Evangelical Agnosticism William Henry Young 37 To Refuse to Be a God: Religious Humanism of the Future Khoren Arisian 41 The Legacy of Voltaire (Part II) Paul Edwards BOOKS 50 Arguing About Old-Time Christianity Antony Flew VIEWPOINTS 51 Child Abuse: Myth or Reality? Vern L. Bullough 52 A Humanist's Lack of Options Sarah Slavin 53 Sobriety Without Superstition James Christopher 56 IN THE NAME OF GOD 58 CLASSIFIED Editor: Paul Kurtz Associate Editors: Doris Doyle, Steven L. Mitchell, Lee Nisbet, Gordon Stein Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski Contributing Editors: Lionel Abel, author, critic, SUNY at Buffalo; Paul Beattie, president, Fellowship of Religious Humanists; Jo-Ann Boydston, director, Dewey Center; Laurence Briskman, lecturer, Edinburgh University, Scotland; Vern Bullough, historian, State University of New York College at Buffalo; Albert Ellis, director, Institute for Rational Living; Roy P. -

A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England Max K

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England Max K. Brinson University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Brinson, Max K., "A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1595. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1595 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Max Brinson University of Central Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in History, 2011 University of Central Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in Creative Writing, 2011 May 2016 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. Dr. Joshua Smith Thesis Director Dr. Lynda Coon Dr. Charles Muntz Committee Member Committee Member Abstract During the Viking Age, the Christian Anglo-Saxons in England found warnings and solace in the biblical text of Ezekiel. In this text, the God of Israel delivers a dual warning: first, the sins of the people call upon themselves divine wrath; second, it is incumbent upon God’s messenger to warn the people of their extreme danger, or else find their blood on his hands. -

The Quran and the Secular Mind: a Philosophy of Islam

The Quran and the Secular Mind In this engaging and innovative study Shabbir Akhtar argues that Islam is unique in its decision and capacity to confront, rather than accommodate, the challenges of secular belief. The author contends that Islam should not be classed with the modern Judaeo–Christian tradition since that tradition has effectively capitulated to secularism and is now a disguised form of liberal humanism. He insists that the Quran, the founding document and scripture of Islam, must be viewed in its own uniqueness and integrity rather than mined for alleged parallels and equivalents with biblical Semitic faiths. The author encourages his Muslim co-religionists to assess central Quranic doctrine at the bar of contemporary secular reason. In doing so, he seeks to revive the tradition of Islamic philosophy, moribund since the work of the twelfth century Muslim thinker and commentator on Aristotle, Ibn Rushd (Averroës). Shabbir Akhtar’s book argues that reason, in the aftermath of revelation, must be exer- cised critically rather than merely to extract and explicate Quranic dogma. In doing so, the author creates a revolutionary form of Quranic exegesis with vitally significant implications for the moral, intellectual, cultural and political future of this consciously universal faith called Islam, and indeed of other faiths and ideologies that must encounter it in the modern secular world. Accessible in style and topical and provocative in content, this book is a major philosophical contribution to the study of the Quran. These features make it ideal reading for students and general readers of Islam and philosophy. Shabbir Akhtar is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, USA.