Chapter-2 the Study Area, Terrain Profile and Human Geographical Mosaic of Sikkim 47

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

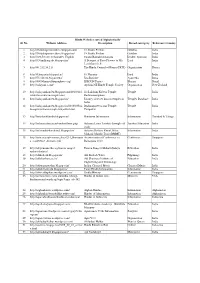

List of Bridges in Sikkim Under Roads & Bridges Department

LIST OF BRIDGES IN SIKKIM UNDER ROADS & BRIDGES DEPARTMENT Sl. Total Length of District Division Road Name Bridge Type No. Bridge (m) 1 East Singtam Approach road to Goshkan Dara 120.00 Cable Suspension 2 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 65.00 Cable Suspension 3 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 92.50 Major 4 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 33.00 Medium Span RC 5 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 19.00 Medium Span RC 6 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 26.00 Medium Span RC 7 East Pakyong Rongli-Delepchand 17.00 Medium Span RC 8 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 17.00 Medium Span RC 9 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 16.00 Medium Span RC 10 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Rumtek Sang 39.00 Medium Span RC 11 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 38.00 Medium Span STL 12 East Pakyong Assam Pakyong 32.00 Medium Span STL 13 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 24.00 Medium Span STL 14 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 32.00 Medium Span STL 15 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 31.50 Medium Span STL 16 East Pakyong Pakyong-Mamring-Tareythan 40.00 Medium Span STL 17 East Pakyong Rongli-Delepchand 9.00 Medium Span STL 18 East Singtam Duga-Pacheykhani 40.00 Medium Span STL 19 East Singtam Sangkhola-Sumin 42.00 Medium Span STL 20 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 29.00 Medium Span STL 21 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 12.00 Medium Span STL 22 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 18.00 Medium Span STL 23 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 19.00 Medium Span STL 24 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 25.00 Medium Span STL 25 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 12.00 Medium Span STL 26 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 19.00 Medium Span STL 27 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 28.00 Medium Span STL 28 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Rumtek Sang 25.00 Medium Span STL 29 East Sub - Div -IV Rumtek-Rey-Ranka 53.00 Medium Span STL Sl. -

REQUEST for PROPOSAL (RFP) December, 2016

National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd. (A Government of India Undertaking) CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR AUTHORITY’S ENGINEER FOR (i) Construction of 1000m length Viaduct at Rangpo between Km 51.1 0 to Km 53.90 on Sevoke - Gangtok Road NH-10 (Old NH- 31A) in the State of West Bengal/Sikkim. (ii)Construction of upgradation of existing road to 2-lane with paved shoulder including geometric improvement from Km. 0.00 0to Km. 26.706 in Rhenok- Rorathang-Pakyong of NH-717A on EPC basis under SARDP-NE Phase ‘Á’ in the State of Sikkim. (iii) Construction/upgradation of existing road to 2-lane with paved shoulders including geometric improvement of NH-510 from Km 0.00 to Km 32.5 (Singtam-Tarku-Rabongla-Legship-Gyalshing) on EPC basis under SARDP- NE Phase ‘A’ in the State of Sikkim. REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) December, 2016 National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited 3rd Floor, Press Trust of India Building, 4, Parliament Street, New Delhi – 110001. CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR AUTHORITY’S ENGINEER FOR (i)Construction of 1000m length Viaduct at Rangpo between Km 51.1 0 to Km 53.90 on Sevoke - Gangtok Road NH-10 (Old NH- 31A) in the State of West Bengal/Sikkim.(ii)Construction of upgradation of existing road to 2-lane with paved shoulder including geometric improvement from Km. 0.00 0to Km. 26.706 in Rhenok-Rorathang-Pakyong of NH-717A on EPC basis under SARDP-NE Phase ‘Á’ in the State of Sikkim. (iii)Construction/upgradation of existing road to 2-lane with paved shoulders including geometric improvement of NH-510 from Km 0.00 to Km 32.5 (Singtam-Tarku-Rabongla-Legship-Gyalshing) on EPC basis under SARDP-NE Phase ‘A’ in the State of Sikkim. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Shortlisted Candidate for the Post of Office Superintendent

1 SHORTLISTED CANDIDATE FOR THE POST OF OFFICE SUPERINTENDENT SL. Name and Address of the Applicant NO. (Contact & Email Id) 1. Mr. Amit Gazmer S/o of Mr. Shri Bhakta Badr. Gazmer High Court of Sikkim, Gangtok 9593883774 2. Mr. Abhay Kumar, S/o Mr. Harendra Prasad Yadav At-2M/97 B H Colony Bhoothnath,Road Kankarbagh, Patna 9708726701 7011287320 3. Ms. Alina Rai, D/O Ganga Prasad rai Singithang, South Sikkim 9432092096, 78728, 93846 [email protected] 4. Ms. Aruna Chhetri, D/o Mr Kamal Das Chjhetri R.o. Upper Syari, Gangtok, East Sikkim 78729-69762 [email protected] 5. Ms. Alenla Bhutia, D/o Mr. Tashi Tobden Bhutia 51/2, Upper Gumpa Ghurpisey, Namchi,South Sikkim 737126 8597643493 [email protected] 6. Ms. Arati Chettri D/o Mr.Prahlad Chettri Kartak Busty, Namchaybung Pakyong, East Sikkim 7076052811 [email protected] 7. Mr. Allen Subba D/o. Mr. Budhi Man Subba Chota Singtam, Ranipool, East Sikkim 7872970355 8. Mr. Abinash Pradhan, S/o Mr. Purna Bdr. Pradhan Aritar Mareydara, East Sikkim. 8016772039 9. - Ms. Anu Chettri D/o Mr. bal Brd Chettri - Tallo Syari PW Syari, Tadong, East Sikkim. 10. - Mr. Abishek Tamang S/o Mr. Karma Tamang - Rongneck, Maneydara, East Sikkim. - 8637810455 11. - Mr. Amit Manger, S/o Mr. Damber Singh Manger - Sumbuk, Kamarey, South Sikkim. - 9593380984, 7908595546 12. - Mr. Abhishek Chettri, S/o Mr. Purna Bdr Chettri - Dikchu, East Sikkim. - 9609703318, 9832655515 13. Mr. Ajay Chettri, S/o Late Sitaram Chettri Mengwa Forest, Teesta Bazar, W.B. 9475659679 2 14. Mr. Attendra Raj Bagdas, S/o Shri Anil Kr Bagdas Development Area, Gangtok. -

Ministry of Road, Transport & Highways Government of India

MINISTRY OF ROAD, TRANSPORT & HIGHWAYS GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DETAILED PROJECT REPORT FOR WIDENING TO 2-LANE OF NH 510 (SINGTAM-TARKU-RABONGLA-LEGSHIP-GYALSHING) IN THE STATE OF SIKKIM DETAILED PROJECT REPORT VOLUME – I: MAIN REPORT AUGUST- 2016 CM ENGINEERING & SOLUTION House No. –1473A, Maruti Vihar, Gurgaon, Haryana – 122002,Tel – 0124 –4255138 Mobile No – 09811406386/09911052266, Email- [email protected] NHIDCL SIKKIM UNIT GOVERNMENT OF MIZORAM PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT - - oo - - DETAILED PROJECT REPORT FOR WIDENING TO 2-LANE OF NH 510 (SINGTAM-TARKU-RABONGLA-LEGSHIP-GYALSHING) IN THE STATE OF SIKKIM Name of Road :NH-54 within Sikkim (KM 00+00 TO KM- 32+50) Length of road : 32.50 Km VOLUME - I MAIN REPORT TABLE OF CONTENT S/N DESCRIPTION PAGE NO. 1 Executive Summary: (1 - 15) 2 Section 1: Introduction (16 - 19) 3 Section 2:Socio-Economic Profile (20 - 29) 4 Section 3: Investigations Engineering Surveys and (30 - 34) 5 Section 4:Design Standards and Specifications (35 - 43) 6 Section 5:Engineering Designs and Construction Proposals (44 - 50) 7 Section 6:Environmental Impact Assessment (51 - 58) 8 Section 7:Materials, Labours and Equipments (59 - 63) 9 Section 8:Quantities and Project Costs (64 - 66) 10 Section 9:Implementation Programme (67 - 68) 11 Section 10:Maintenance of Existing Road (69 - 70) NHIDCL Detailed Project Report for NH-510 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION Recognizing the current inadequate transportation infrastructure facility of the country and the vital role transportation sector plays in the accelerated economic growth of the country, the Government of India has placed a high priority in this sector's development to meet the current and future highway transportation needs. -

List of Selected Candidates for the Post of Junior Accountant. SN Name and Address of the Candidate 1. Aabi Rai S/O Bhanu Rai R

List of selected candidates for the post of Junior Accountant. SN Name and Address of the Candidate 1. Aabi Rai S/o Bhanu Rai R/o West Pendam East Sikkim M: 7908126219/ 9593775597 2. Amit Gazmer S/o Bhakta Bdr. Gazmer R/o Kurseong, West Bengal M. 9593883774 3. Andrea Tenzing Lepcha D/o Nima Tenzing Lepcha R/o Mangan North Sikkim M: 7001031464 4. Anjali Bhitrikoti D/o Birkha Bdr. Bhitrikoti R/o Rhenock Bazar, E. Sikim M. 9083886531/7001020829 5. Anjana Pradhan D/o Purna Kr. Pradhan R/o Rhenock, East Sikkim M. 7719274436 6. Anoj Rai S/o Shyam Bdr. Rai R/o Zoom, West Sikkim M. 9647933777 7. Anugra Rasaily D/o G.B. Rasaily R/o Namchi, South Sikkim M. 9679164002 8. Anusha Subba D/o Beath Kumar Subba R/o Assam Lingzey, E. Sikkim M. 7908757463 9. Arbin Rai S/o Subash Rai R/o Gangtok, East Sikkim M: 9832643872 10. Aruna Tamang D/o Tshering Dorjee Tamang R/o West Pendam, E. Sikkim M. 7602461322 11. Ashib Yonzone S/o Sanjay Yonzone R/o Arithang, East Sikkim M. 8116390843 12. Barsha Chettri D/o Jar Singh Chettri R/o Ravangla, South Sikkim M.7602696074/8370814583 13. Bhumika Laghun W/o Prabin Khati R/o Namchi, South Sikkim M. 14. Bidhya Chettri D/o Deepak Kumar Chettri R/o Namchi, South Sikkim M:9641241362/7550970461 15. Birendra Darjee S/o Kesher Singh Darjee R/o Lingmoo, South Sikkim M. 9083120237 16. Biru Subba S/o Dak Man Limbu R/o Kidhang, West Sikkim M: 7407955030 17. -

Society and Economy of Sikkim Under Namgyal Rulers (1640– 1890)

SOCIETY AND ECONOMY OF SIKKIM UNDER NAMGYAL RULERS (1640– 1890) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO GAUHATI UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY IN THE FACULTY OF ARTS KESHAV GAUTAM Department of History Gauhati University 2014 I S Mumtaza Khatun Ph-09864031679 Department of History Email. [email protected] Gauhati University Gopinath Bordoloi Nagar Guwahati-781014 Assam, India CERTIFICATE Certified that Mr. Keshav Gautam has worked under my supervision for the thesis entitled “Society and Economy of Sikkim Under Namgyal Rulers (1640-1890) ”. He fulfills all the requirements prescribed under the Ph.D. rules of the Gauhati University. The thesis is the product of the scholar’s own investigation in the subject and the scholar has incorporated the suggestions made at the time of pre-submission seminar. I further declare that this thesis or any part thereof has not been submitted to any other university or institution for any degree. (I S Mumtaza Khatun) DECLARATION BY THE CANDIDATE I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “Society and Economy of Sikkim Under Namgyal Rulers (1640-1890)” is prepared by me and I follow all the rules and regulations of Gauhati University. The thesis was not submitted by me for any research degree to the Gauhati University or any other University or institution . Date: (Keshav Gautam) Place: Research Scholar Department of History Gauhati University II Acknowledgement The work is the culmination of the help and encouragement of many individuals which needs to be gratefully acknowledged. I am deeply indebted to my supervisor Dr. I. S. Mumtaza Khatun, Associate Professor, Department of History, Gauhati University, for her constant guidance, motivation and valuable suggestions. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

GOVERNMENT of SIKKIM HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT GANGTOK-737101 No: 678/Adm/HRDD Dated: 21/07/2018 OFFICE ORDER With

GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT GANGTOK-737101 No: 678/Adm/HRDD Dated: 21/07/2018 OFFICE ORDER With the approval of the competent authority, the following School Heads, Post Graduate Teachers, Graduate Teachers, Primary Teachers and Pre-Primary Teachers are hereby posted as mentioned against their names. Sl. Name Designation Presently To be No posted transferred 01. Sanjay Principal Kitam SSS, Legship SSS, Acharya South West 02. Lata Principal DIET, West Kitam SSS, Sharma South 03. Rajyashree Principal Attached to Gerethang SSS, Subba JD Office, West South 04. P.K. Principal Legship SSS, Ben SSS, South Sharma West 05. Angela HM, SS Ben SSS, JD Office, Chime South South Chingapa 06. Lakhi HM, SS Chota- Sudunglakha Doma Samdong SS, East Bhutia SSS, West 07. Priya Lama HM, SS Melli-Gumpa Mikhola SS, SSS, South South 08. Punam HM, SS Attached to Lower Bermiok Pradhan JD Office, SS, West South 09. Tulshi Ram HM, SS Lower Milling SS, West Sharma Bermiok SS, West 10. Ranu Rai HM, SS Kateng SS, Penlong SS, South East 11. Surjay HM, SS Zoom SS, Burul SS, Pradhan West South 12. Bhim HM, SS Burul SS, Zoom SS, West Samsher South Chettri 13. Thendup HM-SS Attached to Primary Namgyal JD(North) Education, HQ Kazi Office till further orders 14. Laxuman HM, SS Bermiok Khandu SS, Tamang SSS, West West 15. Anup HM, JHS Mikhola SS, Gurung Gaon Kumar South JHS, South Dural 16. Yadav HM, JHS Phamtam Bering JHS, Pokhrel JHS, North East 17. Phuchung HM, JHS Bering JHS, Phamtam JHS, Duplay East North Kazi 18. -

Restricted Area Permit (RAP) to the Foreigner and Grant of PAP/ RAP for the Specific Purpose (I.E

PROTECTED AND RESTRICTED AREAS 1. Under the Foreigners (Protected Areas) Order, 1958, all areas falling between the ‘Inner line’, as defined in the said order, and the International Border of the State have been declared as Protected Area. Protected Areas are located in the following States:- (i) Whole of Arunachal Pradesh (ii) Parts of Himachal Pradesh (iii) Parts of Jammu & Kashmir (iv) Whole of Manipur (v) Whole of Mizoram (vi) Whole of Nagaland (vii) Parts of Rajasthan (viii) Whole of Sikkim (partly in Protected Area and partly in Restricted Area) (ix) Parts of Uttarakhand As per instructions issued by the Ministry of Home Affairs on 30.12.2010, the entire area of the States of Manipur, Mizoram and Nagaland has been excluded from the Protected Area regime notified under the Foreigners (Protected Areas) Order 1958, initially for a period of one year w.e.f. 1.1.2011, which has been extended from time to time. This relaxation has been extended till 31.12.2022 subject to the following conditions:- (i) Citizens of Afghanistan, China and Pakistan and foreign nationals having their origin in these countries would continue to require prior approval of the Ministry of Home Affairs before their visit to the States of Manipur, Mizoram and Nagaland. (ii) All foreigners visiting these States will register themselves with the Foreigners Registration Officer (FRO) of the State/District they visit within 24 hours of their arrival. Myanmar nationals visiting the States of Manipur, Mizoram and Nagaland are also excluded from the requirement of obtaining a Protected Area Permit till 31.12.2022 subject to the following conditions:- (i) All such Myanmar nationals shall obtain a visa from the Indian Missions/ Posts abroad or e-Tourist Visa facility which has been made available to the nationals of Myanmar under the existing procedure. -

Bulletin of Tibetology

Bulletin of Tibetology VOLUME 41 NO. 1 MAY 2005 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK, SIKKIM The Bulletin of Tibetology seeks to serve the specialist as well as the general reader with an interest in the field of study. The motif portraying the Stupa on the mountains suggests the dimensions of the field. Bulletin of Tibetology VOLUME 41 NO. 1 MAY 2005 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK, SIKKIM Patron HIS EXCELLENCY V RAMA RAO, THE GOVERNOR OF SIKKIM Advisor TASHI DENSAPA, DIRECTOR NIT Editorial Board FRANZ-KARL EHRHARD ACHARYA SAMTEN GYATSO SAUL MULLARD BRIGITTE STEINMANN TASHI TSERING MARK TURIN ROBERTO VITALI Editor ANNA BALIKCI-DENJONGPA Guest Editor for Present Issue MARK TURIN Assistant Editors TSULTSEM GYATSO ACHARYA VÉRÉNA OSSENT THUPTEN TENZING The Bulletin of Tibetology is published bi-annually by the Director, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok, Sikkim. Annual subscription rates: South Asia, Rs150. Overseas, $20. Correspondence concerning bulletin subscriptions, changes of address, missing issues etc., to: Administrative Assistant, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok 737102, Sikkim, India ([email protected]). Editorial correspondence should be sent to the Editor at the same address. Submission guidelines. We welcome submission of articles on any subject of the history, language, art, culture and religion of the people of the Tibetan cultural area although we would particularly welcome articles focusing on Sikkim, Bhutan and the Eastern Himalayas. Articles should be in English or Tibetan, submitted by email or on CD along with a hard copy and should not exceed 5000 words in length. The views expressed in the Bulletin of Tibetology are those of the contributors alone and not the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology.