Semantic Clusters: Warfare, Hunting and Shipping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KHAZAR UNIVERSITY Faculty

KHAZAR UNIVERSITY Faculty: School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department: English Language and Literature Specialty: English Language and Literature MA THESIS Theme: Historical English Borrowings Master Student: Aynura Huseynova Supervisor: Eldar Shahgaldiyev, Ph.D. January -2014 1 Contents Introduction…………………………………………………....3 – 9 Chapter I: Survey of the English language. Word Stock……………… 10-16 To which group does English language belong? …………… 16-23 Historical Background…………..………………................... 23-27 The historical periods of English language…………………. 27-31 Chapter II: English Borrowings and Their Structural Analysis. The History of English Language (Historical Approach)…… 32-68 Chapter III: Tendency of Future Development of English Borrowings……………………………................... 69-72 Conclusion…………………………………………............ 73-74 References………………………………………………… 75-76 2 INTRODUCTION Although at the end of the every century, learning Latin, Greek, Arabic, Spanish, German, French language spread while replacing each other. But for two centuries the English language got non-substitutive, unchanged status as the world's international language and learning of this language began to spread in our republic widely. The cause of widely spread of the English language all over the not only being the powerful maritime empire Great Britain‘s global colonization policy, but also was easy to master language. It is known that among world languages English has rich vocabulary reserve. The changes in nation's economic-political and cultural life, new production methods, new scientific achievements and technological progress, main turn in agriculture, changes in social structure, science, culture, trade, the development of literature, the creation of the state, and etc., such events were the cause of further enrichment and affect the structure of the dictionary of the English language. -

Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Václav Blažek (Masaryk University of Brno, Czech Republic) On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: Survey The purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo-European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non-Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian 0.3. Vladimir Georgiev (1981, 363) included in his Indo-European classification some of the relic languages, plus the languages with a doubtful IE affiliation at all: Tocharian Northern Balto-Slavic Germanic Celtic Ligurian Italic & Venetic Western Illyrian Messapic Siculian Greek & Macedonian Indo-European Central Phrygian Armenian Daco-Mysian & Albanian Eastern Indo-Iranian Thracian Southern = Aegean Pelasgian Palaic Southeast = Hittite; Lydian; Etruscan-Rhaetic; Elymian = Anatolian Luwian; Lycian; Carian; Eteocretan 0.4. -

HYPERBOREANS Myth and History in Celtic-Hellenic Contacts Timothy P.Bridgman HYPERBOREANS MYTH and HISTORY in CELTIC-HELLENIC CONTACTS Timothy P.Bridgman

STUDIES IN CLASSICS Edited by Dirk Obbink & Andrew Dyck Oxford University/The University of California, Los Angeles A ROUTLEDGE SERIES STUDIES IN CLASSICS DIRK OBBINK & ANDREW DYCK, General Editors SINGULAR DEDICATIONS Founders and Innovators of Private Cults in Classical Greece Andrea Purvis EMPEDOCLES An Interpretation Simon Trépanier FOR SALVATION’S SAKE Provincial Loyalty, Personal Religion, and Epigraphic Production in the Roman and Late Antique Near East Jason Moralee APHRODITE AND EROS The Development of Greek Erotic Mythology Barbara Breitenberger A LINGUISTIC COMMENTARY ON LIVIUS ANDRONICUS Ivy Livingston RHETORIC IN CICERO’S PRO BALBO Kimberly Anne Barber AMBITIOSA MORS Suicide and the Self in Roman Thought and Literature Timothy Hill ARISTOXENUS OF TARENTUM AND THE BIRTH OF MUSICOLOGY Sophie Gibson HYPERBOREANS Myth and History in Celtic-Hellenic Contacts Timothy P.Bridgman HYPERBOREANS MYTH AND HISTORY IN CELTIC-HELLENIC CONTACTS Timothy P.Bridgman Routledge New York & London Published in 2005 by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10016 http://www.routledge-ny.com/ Published in Great Britain by Routledge 2 Park Square Milton Park, Abingdon Oxon OX14 4RN http://www.routledge.co.uk/ Copyright © 2005 by Taylor & Francis Group, a Division of T&F Informa. Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photo copying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

525 First Records of the Chewing Lice (Phthiraptera) Associ- Ated with European Bee Eater (Merops Apiaster) in Saudi Arabia Azza

Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology, Vol.42, No.3, December 2012 J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol., 42(3), 2012: 525 – 533 FIRST RECORDS OF THE CHEWING LICE (PHTHIRAPTERA) ASSOCI- ATED WITH EUROPEAN BEE EATER (MEROPS APIASTER) IN SAUDI ARABIA By AZZAM EL-AHMED1, MOHAMED GAMAL EL-DEN NASSER1,4, MOHAMMED SHOBRAK2 AND BILAL DIK3 Department of Plant Protection1, College of Food and Agriculture Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Department of Biology2, Science College, Ta'if University, Ta'if, Saudi Arabia, and Department of Parasitology3, Col- lege of Veterinary Medicine, University of Selçuk, Alaaddin Keykubat Kampüsü, TR-42075 Konya, Turkey. 4Corresponding author: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract The European bee-eater (Merops apiaster) migrates through Saudi Arabia annu- ally. A total of 25 individuals of this species were captured from three localities in Riyadh and Ta'if. Three species of chewing lice were identified from these birds and newly added to list of Saudi Arabia parasitic lice fauna from 160 lice individu- als, Meromenopon meropis of suborder Amblycera, Brueelia apiastri and Mero- poecus meropis of suborder Ischnocera. The characteristic feature, identification keys, data on the material examined, synonyms, photo, type and type locality are provide to each species. Key words: Chewing lice, Amblycera, Ischnocera, European bee-eater, Merops apiaster, Saudi Arabia. Introduction As the chewing lice species diversity is Few studies are available on the bird correlated with the bird diversity, the lice of migratory and resident birds of Phthiraptera fauna of Saudi Arabia ex- the Middle East. Hafez and Madbouly pected to be high as at least 444 wild (1965, 1968 a, b) listed some of the species of birds both resident and mi- chewing lice of wild and domestic gratory have been recorded from Saudi birds of Egypt. -

Constitucionalismo En El Siglo Xxi

La Constitución de 1917 fue la culminación del proceso revolucionario que dio origen al México del siglo XX. Para conmemorar el Centenario y la vigencia de nuestra Carta Magna es menester conocer el contexto nacional e internacional en que se elaboró y cómo es que ha regido la vida de los mexicanos durante un siglo. De ahí la importancia de la presente obra. • México y la Constitución de 1917 • El Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México (INEHRM) tiene la satisfacción de publicar, con el Senado de la Repú- blica y el Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM, la obra “México Constitucionalismo en el siglo XXI y la Constitución de 1917”. En ella destacados historiadores y juristas, poli- XXI tólogos y políticos, nos dan una visión multidisciplinaria sobre el panorama A cien años de la aprobación de la Constitución de 1917 histórico, jurídico, político, económico, social y cultural de nuestro país, Francisco José Paoli Bolio desde la instalación del Congreso Constituyente de 1916-1917 hasta nues- tros días. Científicos sociales y escritores hacen, asimismo, el seguimiento de la evolución que ha tenido el texto constitucional hasta el tiempo presente en el siglo Constitucionalismo A cien años de la aprobación de la Constitución de 1917 de la Constitución A cien años de la aprobación y su impacto en la vida nacional, así como su prospectiva para el siglo XXI. Francisco José Paoli Bolio Paoli Francisco José SENADO DE LA REPÚBLICA - LXIII LEGISLATURA SECRETARÍA DE CULTURA INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDIOS -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Vassilis Lambropoulos C. P. Cavafy Professor of Modern Greek Professor of Classical Studies and Comparative Literature University of Michigan I. PERSONAL Born 1953, Athens, Greece II. EDUCATION University of Athens (Greece), Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 1971-75 (B.A. 1975) University of Thessaloniki (Greece), Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 1976- 79 (Ph.D. 1980) Dissertation Topic: The Poetics of Roman Jakobson Dissertation Title: “Roman Jakobson's Theory of Parallelism” University of Birmingham (England), School of Hellenic and Roman Studies and Department of English, 1979-81, Postdoctoral Fellow III. PROFESSIONAL HISTORY The Ohio State University, Dept. of Near Eastern, Judaic, and Hellenic Languages and Literatures (1981-96) and Dept. of Greek and Latin, Modern Greek Program (1996-99): Assistant (1981-87), Associate (1987-92), and Professor (1992-99) of Modern Greek Dept. of Comparative Studies: Associate Faculty (1989-99) Dept. of History: Associate Faculty (1997-99) University of Michigan, Departments of Classical Studies and Comparative Literature (1999-): C. P. Cavafy Professor of Modern Greek Lambropoulos CV 2 2 IV. FELLOWSHIPS, HONORS and AWARDS Greek Ministry of Culture, Undergraduate Scholarship, University of Athens (Greece), 1971-72 Greek National Scholarship Foundation, Postdoctoral Fellowship, University of Birmingham (England), 1979-81 National Endowment for the Humanities Scholarship for participation in NEH Summer Seminar for College Teachers, "Greek Concepts of Myth and Contemporary Theory," directed by Gregory Nagy, Harvard University, July-August 1985 National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship for University Teachers, 1992-93 Ohio State University Distinguished Scholar Award (one of six campus-wide annual awards), 1994 LSA/OVPR Michigan Humanities Award (one of ten College-wide annual one-semester fellowships), 2005 Outstanding Professor of the Year Award, Office of Greek Life, University of Michigan, April 2005 The Stavros S. -

Keltiké Makhaira. on a La Tène Type Sword from the Sanctuary of Nemea

JAN KYSELA · STEPHANIE KIMMEY KELTIKÉ MAKHAIRA. ON A LA TÈNE TYPE SWORD FROM THE SANCTUARY OF NEMEA An iron sword (IL 296) was discovered in Well K14:4 in the sanctuary of Zeus at Nemea (today Archaia Nemea, Corinthia / GR) in 1978 (fg. 1, N). Although promptly published (Stephen G. Miller 1979; 2004) and displayed in the local archaeological museum, and known therefore for four decades now, it has received only very little attention so far (the only exception being a brief note in Baitinger 2011, 76). The present paper is an attempt to make up for this disinterest. DESCRIPTION The iron sword has a straight symmetrical two-edged blade tapering towards the point with some preserved wooden elements of the hilt (fg. 2). The measurements of the sword are as follows: overall L. c. 83 cm; blade L. c. 72 cm; blade W. at the hilt 4.9 cm; tang L. c. 11 cm; L. of the preserved wooden handle 6.5 cm; W. of the guard 5 cm; L. of rivets in the hilt 24 mm. The sword has not been weighed. The object was re- stored after its discovery; no information about the nature and extent of this intervention has been pre- served, however. It underwent a mechanical cleaning and was heavily restored with epoxy 1. A later and duly documented conservation in 2010 aimed mostly at the stabilisation of the object. The blade is bent but complete. In several spots (particularly in its upper fourth and towards its very end), the remains of iron sheet cling to the blade surface. -

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period Ryan

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period by Ryan Anthony Boehm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emily Mackil, Chair Professor Erich Gruen Professor Mark Griffith Spring 2011 Copyright © Ryan Anthony Boehm, 2011 ABSTRACT SYNOIKISM, URBANIZATION, AND EMPIRE IN THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD by Ryan Anthony Boehm Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Emily Mackil, Chair This dissertation, entitled “Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period,” seeks to present a new approach to understanding the dynamic interaction between imperial powers and cities following the Macedonian conquest of Greece and Asia Minor. Rather than constructing a political narrative of the period, I focus on the role of reshaping urban centers and regional landscapes in the creation of empire in Greece and western Asia Minor. This period was marked by the rapid creation of new cities, major settlement and demographic shifts, and the reorganization, consolidation, or destruction of existing settlements and the urbanization of previously under- exploited regions. I analyze the complexities of this phenomenon across four frameworks: shifting settlement patterns, the regional and royal economy, civic religion, and the articulation of a new order in architectural and urban space. The introduction poses the central problem of the interrelationship between urbanization and imperial control and sets out the methodology of my dissertation. After briefly reviewing and critiquing previous approaches to this topic, which have focused mainly on creating catalogues, I point to the gains that can be made by shifting the focus to social and economic structures and asking more specific interpretive questions. -

Vowel Change in English and German: a Comparative Analysis

Vowel change in English and German: a comparative analysis Miriam Calvo Fernández Degree in English Studies Academic Year: 2017/2018 Supervisor: Reinhard Bruno Stempel Department of English and German Philology and Translation Abstract English and German descend from the same parent language: West-Germanic, from which other languages, such as Dutch, Afrikaans, Flemish, or Frisian come as well. These would, therefore, be called “sister” languages, since they share a number of features in syntax, morphology or phonology, among others. The history of English and German as sister languages dates back to the Late antiquity, when they were dialects of a Proto-West-Germanic language. After their split, more than 1,400 years ago, they developed their own language systems, which were almost identical at their earlier stages. However, this is not the case anymore, as can be seen in their current vowel systems: the German vowel system is composed of 23 monophthongs and 8 diphthongs, while that of English has only 12 monophthongs and 8 diphthongs. The present paper analyses how the English and German vowels have gradually changed over time in an attempt to understand the differences and similarities found in their current vowel systems. In order to do so, I explain in detail the previous stages through which both English and German went, giving special attention to the vowel changes from a phonological perspective. Not only do I describe such processes, but I also contrast the paths both languages took, which is key to understand all the differences and similarities present in modern English and German. The analysis shows that one of the main reasons for the differences between modern German and English is to be found in all the languages English has come into contact with in the course of its history, which have exerted a significant influence on its vowel system, making it simpler than that of German. -

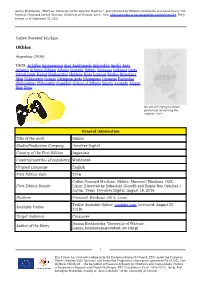

OMC | Data Export

Joanna Bieńkowska, "Entry on: Okhlos by Coffee Powered Machine ", peer-reviewed by Elżbieta Olechowska and Susan Deacy. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2018). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/309. Entry version as of September 25, 2021. Coffee Powered Machine Okhlos Argentina (2016) TAGS: Achilles Agamemnon Ajax Andromeda Aphrodite Apollo Ares Artemis Athena/ Athene Athens Comedy Delphi Dionysus Ephesus Gods Greek Gods Hades Hephaestus Hermes Hero Lemnos Medea Menelaus Mob Ochlocracy Ochlos Olympian gods Olympians Olympus Patroclus Philosopher Philosophy Poseidon School of Athens Sparta Tragedy Trojan War Zeus We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Title of the work Okhlos Studio/Production Company Devolver Digital Country of the First Edition Argentina Country/countries of popularity Worldwide Original Language English First Edition Date 2016 Coffee Powered Machine. Okhlos. Microsoft Windows, OSX, First Edition Details Linux. [Directed by Sebastián Gioseffi and Roque Rey Ordoñez.] Austin, Texas: Devolver Digital, August 18, 2016. Platform Microsoft Windows, OS X, Linux Trailer Available Online: youtube.com (accessed: August 20, Available Onllne 2018) Target Audience Crossover Joanna Bieńkowska, University of Warsaw, Author of the Entry [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood... The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges, ERC Consolidator Grant (2016–2021), led by Prof. Katarzyna Marciniak, Faculty of “Artes Liberales” of the University of Warsaw. -

GREEKS and PRE-GREEKS: Aegean Prehistory and Greek

GREEKS AND PRE-GREEKS By systematically confronting Greek tradition of the Heroic Age with the evidence of both linguistics and archaeology, Margalit Finkelberg proposes a multi-disciplinary assessment of the ethnic, linguistic and cultural situation in Greece in the second millennium BC. The main thesis of this book is that the Greeks started their history as a multi-ethnic population group consisting of both Greek- speaking newcomers and the indigenous population of the land, and that the body of ‘Hellenes’ as known to us from the historic period was a deliberate self-creation. The book addresses such issues as the structure of heroic genealogy, the linguistic and cultural identity of the indigenous population of Greece, the patterns of marriage be- tween heterogeneous groups as they emerge in literary and historical sources, the dialect map of Bronze Age Greece, the factors respon- sible for the collapse of the Mycenaean civilisation and, finally, the construction of the myth of the Trojan War. margalit finkelberg is Professor of Classics at Tel Aviv University. Her previous publications include The Birth of Literary Fiction in Ancient Greece (1998). GREEKS AND PRE-GREEKS Aegean Prehistory and Greek Heroic Tradition MARGALIT FINKELBERG cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521852166 © Margalit Finkelberg 2005 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Recognition and its Dilemmas in Roman Epic Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4hn808p4 Author Librandi, Diana Publication Date 2021 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Recognition and its Dilemmas in Roman Epic A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics by Diana Librandi 2021 © Copyright by Diana Librandi 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Recognition and its Dilemmas in Roman Epic by Diana Librandi Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor Francesca Katherine Martelli, Chair The present dissertation examines the widespread presence of tropes of tragic recognition in Roman epic poetry from an interdisciplinary perspective. I argue that Roman epic poets draw at once on tragedy and ancient philosophy to address the cognitive instability generated by civil war, an event which recurrently marks the history of Rome since its foundation. When civil conflicts arise, the shifting categories of friend and enemy, kin and stranger, victor and vanquished, generate a constant renegotiation of individual identities and interpersonal relationships. It is in light of these destabilizing changes that I interpret the Roman epic trend of pairing civil war narratives with instances of tragic recognition. Far from working exclusively as a plot device or as a marker of the interaction between the genres of epic and tragedy, tropes of tragic recognition in Roman epic are conducive to exploring the epistemological and ethical dilemmas posed by civil war.