Comparing Turkish and Pakistani Teachers' Professionalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OVERDUE FINES: 25¢ Por Day Per Item RETURNING LIBRARY MATERIALS: P'iace in Book Return to Remove Chars

OVERDUE FINES: 25¢ por day per Item RETURNING LIBRARY MATERIALS: P'Iace in book return to remove chars. from circuhtion recon © Copyright by JACQUELINE KORONA TEARE 1980 THE PACIFIC DAILY NEWS: THE SMALL TOWN NEWSPAPER COVERING A VAST FRONTIER By Jacqueline Korona Teare A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS School of Journalism 1980 ABSTRACT THE PACIFIC DAILY NEWS: THE SMALL TOWN NEWSPAPER COVERING A VAST FRONTIER 3y Jacqueline Korona Teare Three thousand miles west of Hawaii, the tips of volcanic mountains poke through the ocean surface to form the le-square- mile island of Guam. Residents of this island and surrounding island groups are isolated from the rest of the world by distance, time and, for some, by relatively primitive means of communication. Until recently, the only non-military, English-language daily news- paper serving this three million-square-mile section of the world was the Pacific Daily News, one of the 82 publications of the Rochester, New York-based Gannett Co., Inc. This study will trace the history of journalism on Guam, particularly the Pacific Daily News. It will show that the Navy established the daily Navy News during reconstruction efforts follow- ing World War II. That newspaper was sold in l950 to Guamanian civilian Joseph Flores, who sold the newspaper in 1969 to Hawaiian entrepreneur Chinn Ho and his partner. The following year, they sold the newspaper now called the Pacific Daily News, along with their other holdings, to Gannett. Jacqueline Korona Teare This study will also examine the role of the Pacific Daily Ngw§_in its unique community and attempt to assess how the newspaper might better serve its multi-lingual and multi-cultural readership in Guam and throughout Micronesia. -

CHAMORRO CULTURAL and RESEARCH CENTER Barbara Jean Cushing

CHAMORRO CULTURAL AND RESEARCH CENTER Barbara Jean Cushing December 2009 Submitted towards the fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Architecture degree. University of Hawaii̒ at Mānoa School of Architecture Spencer Leineweber, Chairperson Joe Quinata Sharon Williams Barbara Jean Cushing 2 Chamorro Cultural and Research Center Chamorro Cultural and Research Center Barbara Jean Cushing December 2009 ___________________________________________________________ We certify that we have read this Doctorate Project and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Architecture in the School of Architecture, University of Hawaii̒ at Mānoa. Doctorate Project Committee ______________________________________________ Spencer Leineweber, Chairperson ______________________________________________ Joe Quinata ______________________________________________ Sharon Williams Barbara Jean Cushing 3 Chamorro Cultural and Research Center CONTENTS 04 Abstract phase 02 THE DESIGN 08 Field Of Study 93 The Next Step 11 Statement 96 Site Analysis 107 Program phase 01 THE RESEARCH 119 Three Concepts 14 Pre‐Contact 146 The Center 39 Post‐Contract 182 Conclusion 57 Case Studies 183 Works Sited 87 ARCH 548 186 Bibliography Barbara Jean Cushing 4 Chamorro Cultural and Research Center ABSTRACT PURPOSE My architectural doctorate thesis, titled ‘Chamorro Cultural and Research Center’, is the final educational work that displays the wealth of knowledge that I have obtained throughout the last nine years of my life. In this single document, it represents who I have become and identifies the path that I will be traveling in the years to follow. One thing was for certain when beginning this process, in that Guam and my Chamorro heritage were to be important components of the thesis. -

An Annotated Bibliography on ESL and Bilingual Education in Guam and Other Areas of Micronesia

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 299 832 FL 017 646 AUTHOR Goetzfridt, Nicholas TITLE An Annotated Bibliography on ESL and Bilingual Education in Guam and Other Areas of Micronesia. SPONS AGENCY Office of Bilingual Education and Minority Languages Affairs (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 112p.; A publioation of Project BEAM. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Bilingual Education; *English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; *Publications; *Resource Materials; Second Language Instruction IDENTIFIERS *Guam; *Micronesia ABSTRACT The bibliography contains 182 annotated and 52 unannotated citations of journal articles, newspaper articles, dissertations, books, program and research reports, and other publications concerning bilingual education and instruction in English as a second language (ESL) in Micronesia. An introductory section gives information on sources for the publications and other information concerning the use of the bibliography. The entries are indexed alphabetically. (MSE) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** An Annotated Bibliography on ESL and Bilingual Education in Guam and Other Areas of Micronesia "PER? ISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS U.S. DEPARTMENTOF EDUCATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY Othce of Educabona. Research and improvement EDUCATIONAL -

An Exploratory Study of Community Trauma and Culturally Responsive Counseling with Chamorro Clients. Patricia Taimanglo Pier University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1998 An exploratory study of community trauma and culturally responsive counseling with Chamorro clients. Patricia Taimanglo Pier University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Pier, Patricia Taimanglo, "An exploratory study of community trauma and culturally responsive counseling with Chamorro clients." (1998). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1257. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1257 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF COMMUNITY TRAUMA AND CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE COUNSELING WITH CHAMORRO CLIENTS A Dissertation Presented by PATRICIA TAIMANGLO PIER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 1998 School and Counseling Psychology Patricia Taimanglo Pier 1998 (5) Copyright by All Rights Reserved AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF COMMUNITY TRAUMA AND CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE COUNSELING WITH CHAMORRO CLIENTS A Dissertation Presented by PATRICIA TAIMANGLO PIER Approved as to style and content by: Allen E. Ivey, Chairperson of Committee ACKINOWLEDGIMKN I S My journey through this paper was made possible by the countless gifts of support, time, and energy from my family, professors, participants, and friends l)r Allen F Ivey, my deepest gratitude for your unconditional faith in my work Dr Janine Robert, I am indebted to you for your enriching energy, keen eye for detail and supportive voice throughout the process Dr. -

Living the Guam Brand Day 1

Guam Visitors Bureau Conference Naʼlåʼlaʼ i Kostumbren Guåhan Ta Naʼfandanñaʼ i Bisitå-ta yan i Kotturå-ta Living the Guam Brand Bringing together our culture and our visitors April 7 - 8, 2011 Hyatt Regency, Tumon Guam Setbison Bisitan Guåhan, CHaCO Guam Visitors Bureau, CHaCO and funding for this e-publication provided by Inangokkon Inadahi Guahan Guam Preservation Trust Table of Contents Na"lå"la" i Kostumbren Guåhan | Living the Guam Brand Ta Na"fandanña" i Bisitå-ta yan i Kotturå-ta | Bringing together our culture and our visitors Day One – Diha 7 gi Abrit 2011 | April 7, 2011 ! 1! Mensåhen Finatto! Unuråpble Eddie Baza Calvo, Governor of Guam !! Welcome Remarks! Honorable Eddie Baza Calvo, Maga"låhen Guåhan ! 5! Hestoria Put i Kostumbre! Gerald S. A. Perez, Consultant, GVB !! History of the Brand! Konsuttånte, Setbision Bisitan Guåhan ! 15! Inadilånton Kostumbre|Binisita ! Rhonda Brauer, Director, !! Put Kotturagi Pumalu na Lugåt siha! Burson Marstellar !! Developing the Brand/Cultural! Direktoran Minaneha, Burson Marstellar !! Tourism in other Destinations ! 21! I pao Guåhan! Sinadora Tina Muña Barnes !! The Guam Essence! Mina"trentai unu na Liheslaturan Guåhan !! Guaha Kottura?! Senator, 31st Guam Legislature !! Got Culture! ! 25! Inembråsian Kostumbren Guåhan-! Judy Flores, Ph.D., !! Hinasso yan Siñenten Kottura! Bisa-Ge"helo", Irensian Kottura yan !! Embracing the Guam Brand! Hiniyong Kumunidåt; Membro, Inetnon !! -Cultural Perspectives! Direktot, Setbision Bisitan Guåhan !! ! ! Vice-Chairperson, Cultural Heritage and !!!! Community Outreach; GVB Board Member ! 31! Inembråsian Kostumbren Guåhan:! Mary Torre, President, !! Hinasso yan Siñenten Endostriha! Guam Hotel and Restaurant Association !! Embracing the Guam Brand:! !! Industry Perspectives ! 43! Sesion Dinestilådu !! Breakout Sessions !! ! 47! 1. Hestoria yan Irensia! Anne P. -

·Aquaculture Development Plan [ for the Territory

. 4 ~ ~ , , '• . n'" ~ ~ I ' I, u ,, • ~ ' ·Aquaculture Development Plan [ For the Territory . · of Guam [ Department ot Commeroe [ ; ',~ • ' [. '• • ~# .• t \ ~ . - ' , ~ • , -~ . ... +7 - .. I , • .,. ' ~ 0. ... ' ..... ~ .. ., ~ .. 0 .··AQUACULTURE It ' DEVELOPMENT / t PLAN For the Territory of,Guam • prepared by: William J. FitzGerald, Jr. .. .. .I .. j ~ • ., Department-- . of Commerce. Government of Guam • .. • June 1982, .- '· The preparation of this publication was financed in part by the Economic Development Administration's Section 302(a) State Planning Grant (Project No. 07-25-01669-04), U. S. Department of Commerce. Partial support was also provided through the U. S. Depart ment of Commerce, National Oceanographic Atmospheric Administration's Coastal Zone Management Program Grant No. NA-79-AA-D-c-Z-098, Guam Coastal Management Program . .. Cover design by Richard San Nicolas 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary PAGE SECTION I HISTORICAL AND POTENTIAL DEVELOPMENT 1. Introduction . .. .. ....... .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. 1 2. • Natural Resources/Opportunities ......................................................... 3 3. Historical Development of Aquaculture on Guam ..... .. .... .. ................... 7 4. Territorial Government Aquaculture Policy .......................................... 9 5. Economic Effects of Aquaculture Development on Guam ........... ....... 11 6. Revenue Generation 14 7. Fisheries Enhancement 16 8. OTEC and Aquaculture 17 SECTION II INSTITUTIONAL ORGANIZATION 8. Agencies and Associations -

US Jurisd.2Qxd

Colonies in Question Supporting Indigenous Movements in the US Jurisdictions A Report from the FUNDING EXCHANGE Written by Surina Khan OCTOBER 2003 2 ABOUT THE FUNDING EXCHANGE ABOUT THE FUNDING EXCHANGE The Funding Exchange is a national network of publicly-supported, community- based foundations. A unique partnership of activists and donors, the Funding Exchange is dedicated to building a base of support for progressive social change through fundraising for local, national and international grantmaking programs. The national office of the Funding Exchange network is located in New York City. Funding Exchange programs serve its member funds along with donors and grantees around the country. The grantmaking program of the Funding Exchange includes three activist advised-funds: The Saguaro Fund supports organizations that serve communities of color and that are organized and led by members of those communities. The fund supports organizing for human and economic justice, with an emphasis on labor, youth, women, immigration, environmental and economic justice issues. The focus is on groups that engage in grassroots organizing; emphasize leadership development; actively involve the rank and file through empowerment, mass education and politicization; prioritize networking and collaboration; and participate in coalitions and organizations doing multi-issue work. The OUT Fund for Lesbian and Gay Liberation supports organizing projects working to build community among lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and transgender people. The OUT Fund seeks projects that address the politics of race, class, gender and sexuality as integral to systems of oppression while working to develop lasting coalitions with other progressive causes. The Paul Robeson Fund for Independent Media supports independent film, video, and radio projects created by grassroots organizations and independent media producers on critical social issues. -

Cultural Diplomacy in the South Pacific

Cultural Diplomacy in the South Pacific Table of Contents: Cultural Diplomacy in the South Pacific 1. Introduction 2. Methodology 3. Contemporary Examples of Public Sector Sponsored Cultural Diplomacy in the South Pacific 3.1 Cook Islands 3.2 Guam 3.3 Kingdom of Tonga 3.4 Niue Island 3.5 Overseas Lands of French Polynesia 3.6 Papua New Guinea 3.7 Republic of Fiji 3.8 Republic of Palau 3.9 Republic of Marshall Islands 3.10 Republic of Vanuatu 4. Conclusion 5. References 1. Introduction Overview of the South Pacific Region The South Pacific is comprised of 20,000 to 30,000 islands which lie south of the Tropic of Cancer. The Pacific Island region covers 20 million square miles of ocean and 117,000 square miles of land, with a population of 8 million people. For the first time, the South Pacific region is facing urbanization, which has brought new challenges to this area. The rates of urban growth in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, both in excess of 6 per cent per annum, are among the highest in the world.1 The islands are commonly grouped into three different divisions; Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. The inhabitants from each of these groups all differ by historical, geographical, language and physical characteristics. Polynesia is located in the south-eastern part of the region, Melanesia is found in the southwest, from the Arafura Sea to the western end of the Pacific Ocean and eastward to Fiji, whilst Micronesia lies in the north. The Pacific islands are classified into a high island group and a low island group. -

Guam Guide Book

Hafa Adai, Each section of the Guam Guide, detailed in the Table of and Contents, is separated using welcome to Guam! different colored latte stones on the margin of each page. This will help you to explore his Guam Guide includes the book and our island easily. Teverything you need to know about our island in one One important thing to keep easy-to-read format. From our in mind as you make your way rich Chamorro culture to our through the Guam Guide is heritage, food, and even that you can find a listing of all historical landmarks that make hotels, restaurants, scenic our island unique, you will find spots, shopping and everything you need to transportation options – along explore our tropical paradise with other members of the in these pages. Guam Visitors Bureau – in the back pocket. Maps can be found throughout the book, particularly in the Please use this listing to help Sightseeing & Landmarks plan your stay on our beautiful section, which offers a island or visit the GVB website detailed listing of WWII sites, at www.visitguam.com. favorite beaches, and other We hope you enjoy your stay Guam hotspots that may be of on Guam, “Where America’s interest to you. day begins.” 1 USING THIS GUIDE CONTENTS Using this Guide. 2 Guam’s Unique Culture and Proud Heritage . 4 Fruits & Flowers of Guam . 6 Village Murals . 7 Your Guam Experience . 8 History of Guam. 10 Planning Your Visit . 16 Getting Around . 19 Family Fun in the Sun . 20 · Beaches . 20 · Outdoor Activities. 24 · Snorkeling . -

Multiple & Overlapping Identities

Research Multiple & Overlapping Identities The Case of Guam Thomas Misco & Lena Lee Introduction is a lack of consciousness about race, with but rather unceasingly changes through a acceptance of the dominant culture as variety of experiences, intentions, desires, Over the last several decades, the superior. The other common stage involves and powers (Foucault, 1966). In other words, discourse of multicultural education has awareness and establishment of non-racist subjectivity is constantly in the process of emphasized the study of ethnic identity identity in order to take responsibility for reproduction and transformation. development in order to better understand social injustice. As a result, each individual’s identity diversity and gain more specific knowledge However, in most of these studies the may not be formed only through their de- about different ethnic groups and ethnic- identity development models have too often pendence on others’ perspectives. Rather, ity. Examining identity acknowledges that ignored several ethnic minority groups a group of people can shape and renew socio-cultural issues are interwoven with within the United States. As Grant (1997) itself, and their individual selves, through individual feelings, thoughts, and fears asserted, ethnic identity involves many dif- a continual process of struggle. that lead people to have certain behavior ferent characteristics such as nationality, Instead of considering ethnic iden- toward themselves as well as others. citizenship, and language. As a result, these tity as an unchangeable and permanent In particular, ethnic identity develop- significant “markers of identity” (p. 9) can be ontological foundation, in this study we ment theory (e.g., Atkinson, Morten, & Sue, related to how each individual juxtaposes view it as multilayered and continually 1979; Cross, 1991; Hardiman, 2001; Har- any given determinant of identity as well as evolving (Bauman, 2003; Foucault, 1966). -

Chapter 3 Describes the Environment and Resources Included Within the Mariana Archipelago FEP

Fishery Ecosystem Plan for the Mariana Archipelago Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council 1164 Bishop Street, Suite 1400 Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 December 19, 2008 Cover Artwork Courtesy of SoJung Song, Saipan Community School, Susupe, Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands i Chapter 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Mariana Archipelago Fishery Ecosystem Plan (FEP) was developed by the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council and represents the first step in an incremental and collaborative approach to implement ecosystem approaches to fishery management in Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Since the 1980s, the Council has managed fisheries throughout the Western Pacific Region through separate species-based fishery management plans (FMP) – the Bottomfish and Seamount Groundfish FMP, the Crustaceans FMP, the Precious Corals FMP, the Coral Reef Ecosystems FMP and the Pelagic FMP. However, the Council is now moving towards an ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management and is restructuring its management framework from species-based FMPs to place-based FEPs. Recognizing that a comprehensive ecosystem approach to fisheries management must be initiated through an incremental, collaborative, and adaptive management process, a multi-step approach is being used to develop and implement the FEPs. To be successful, this will require increased understanding of a range of issues including, biological and trophic relationships, ecosystem indicators and models, and the ecological effects of non-fishing activities on the marine environment. This FEP, in conjunction with the Council's American Samoa Archipelago, Hawaii Archipelago, Pacific Remote Island Areas and Pacific Pelagic FEPs, replaces the Council's existing Bottomfish and Seamount Groundfish, Coral Reef Ecosystems, Crustaceans, Precious Corals and reorganizes their associated regulations into a place-based structure aligned with the FEPs. -

Introduction to Guam Guam Is Also a Gateway to the World and America in Asia

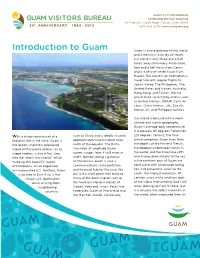

GUAM VISITORS BUREAU SETBISION BISITAN GUAHAN 401 Pale San Vitores Road | Tumon, Guam 96913 1 (671) 646-5278 | www.visitguam.org Introduction to Guam Guam is also a gateway to the world and America in Asia. By air travel, our island is only three and a half hours away from many Asian cities, four and a half hours from Cairns and a little over seven hours from Hawaii. The island is an international travel hub with regular flights to Japan, Korea, The Philippines, The United States and Hawaii, Australia, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. We are proud to be serviced by airlines such as United Airlines, JINAIR, Delta Air Lines, China Airlines, JAL, Eva Air, Korean Air, and Philippine Airlines. Our island is blessed with a warm climate and scenic geography. Guam’s average daily temperature is a pleasant 85 degrees Fahrenheit With a shape reminiscent of a such as China and is ideally situated (29 degrees Celsius). The land footprint left in the sand, Guam is approximately nine hundred miles which comprises Guam rises from the largest and most populated north of the equator. The thirty- the depths of the Mariana Trench, island in Micronesia and just as its two miles of longitude Guam the deepest underwater trench in shape implies, is also a first step covers ranges from 4 to 8 miles in the world, and the limestone cliffs into the “many tiny islands” which width. Besides being a gateway which drop dramatically to the sea make up this beautiful region to Micronesia, Guam is also a in the northern part of Guam are of Micronesia.