The S Elected Asean Nations' Military Capabilities Facing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arms Procurement Decision Making Volume II: Chile, Greece, Malaysia

4. Malaysia Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam* I. Introduction Malaysia has become one of the major political players in the South-East Asian region with increasing economic weight. Even after the economic crisis of 1997–98, despite defence budgets having been slashed, the country is still deter- mined to continue to modernize and upgrade its armed forces. Malaysia grappled with the communist insurgency between 1948 and 1962. It is a democracy with a strong government, marked by ethnic imbalances and affirmative policies, strict controls on public debate and a nascent civil society. Arms procurement is dominated by the military. Public apathy and indifference towards defence matters have been a noticeable feature of the society. Public opinion has disregarded the fact that arms procurement decision making is an element of public policy making as a whole, not only restricted to decisions relating to military security. An examination of the country’s defence policy- making processes is overdue. This chapter inquires into the role, methods and processes of arms procure- ment decision making as an element of Malaysian security policy and the public policy-making process. It emphasizes the need to focus on questions of public accountability rather than transparency, as transparency is not a neutral value: in many countries it is perceived as making a country more vulnerable.1 It is up 1 Ball, D., ‘Arms and affluence: military acquisitions in the Asia–Pacific region’, eds M. Brown et al., East Asian Security (MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass., 1996), p. 106. * The author gratefully acknowledges the help of a number of people in putting this study together. -

Table of Contents Daulat Tuanku!

Newsletter of the Consulate General of Malaysia in Frankfurt am Main – Summer 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS • DAULAT TUANKU! • ASIAN LIBRARY AT GOETHE UNIVERSITY • PHOTO EXHIBITION “UNITY IN DIVERSITY“ • FOOTBALL TOURNAMENT • CHINESE NEW YEAR • #NEGARAKU GATHERING • DIPLOMATIC COUNCIL GALA • TN50 • AMBIENTE 2017 • #NEGARAKU MALAYSIAN FAMILY DAY, DUISBURG • DINNER RECEPTION AT US CG RESIDENCE • IMEX 2017 • CONSULAR CORPS SPRING MEETING • TASTE OF THE WORLD • ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING, PERWAKILAN • ASEAN INVESTMENT FORUM • GMRT DÜSSELDORF • SEMINAR FOR GERMAN-MALAYSIAN UNIVERSITY • GMRT FRANKFURT • 'EID MUBARAK 2017' • CEBIT 2017 DAULAT TUANKU! Sultan Muhammad V has been formally installed as the Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di- Pertuan Agong (King) of Malaysia on 24 April 2017. Tuanku Muhammad Faris Petra, the eldest son of Sultan Ismail Petra Ibni Almarhum Sultan Yahya Petra, was born in Kota Baru on 6 October 1969. He became Sultan of Kelantan in 2010, at the young age of 42, after succeeding his father. His Majesty received early education at Alice Smith International School in Kuala Lumpur. Later, he took up Diplomatic Studies at St. Cross College, Oxford University, and Islamic Studies at the Oxford Centre, Oxford University. He is the Chancellor of Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) and University Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia (UPNM). As Yang di-Pertuan Agong, he also holds full responsibility as Commander-in-Chief of the Malaysian Armed Forces. Pos Malaysia issued 1 stamp, in perforated and imperforate formats, and 1 miniature sheet on 25 April 2017 to commemorate the Sultan Muhammad V is described as a man of a generous and coronation of the new king of Malaysia, Sultan Muhammad V. -

Brigade of Gurkha - Intake 1983 Souvenir

BRIGADE OF GURKHA - INTAKE 1983 SOUVENIR [ A Numberee’s Organization ] -: 1 :- BRIGADE OF GURKHA - INTAKE 1983 SOUVENIR ;DkfbsLo !(*# O{G6]ssf] ofqf #% jif]{ ns]{hjfgaf6 #^ jif{ k|j]z cfhsf] @! cf} ztflAbdf ;dfhdf lzIff, ;jf:Yo, snf, ;:sf/, ;+:s[lt, ;dfrf/ / ;+u7gn] ljZjsf] ab\lnbf] kl/j]zdf ;+ul7t dfWodsf] e"ldsf ctL dxTjk"0f{ /x]sf] x'G5 . To;}n] ;+ul7t If]qnfO{ ljsf;sf] r'r'/f]df klxNofpg] ctL ;s[o dgf]efj /fvL ;dfhdf /x]sf ljz'4 xs / clwsf/ sf] ;+/If0f ;Da4{g ub}{, cfkm\gf] hGdynf] OG6]s ;d'bfodf cxf]/fq nflu/x]sf] !(*# O{G6]sn] #% jif{sf] uf}/jdo O{ltxf; kf/ u/]/ #^ jif{df k|j]z u/]sf] z'e–cj;/df ;j{k|yd xfd|f ;Dk"0f{ z'e]R5'sk|lt xfdL cfef/ JoQm ub{5f}+ . !(*# OG6]ssf] aRrfsf] h:t} afd] ;g]{ kfO{nf z'? ePsf] cfh #^ jif{ k|j]z ubf{;Dd ;+;f/el/ 5l/P/ a;f]af; ul//x]sf gDa/L kl/jf/ ;dIf o:tf] va/ k|:t't ug{ kfp“bf xfdL ;a}nfO{ v'zL nfUg' :jfefljs g} xf] . ljutsf] lbgnfO{ ;Dem]/ Nofpg] xf] eg] sxfnLnfUbf] cgL ;f]Rg} g;lsg] lyof], t/ Psk|sf/sf] /f]rs clg k|;+usf] :d/0f ug{'kg]{ x'G5 . ha g]kfndf a9f] d'l:sNn} etL{ eP/ cfdL{ gDa/ k|fKt ug{' eg]sf] ax't\ sl7g cgL r'gf}ltk"0f{ sfo{ lyof] . z'elrGtssf] dfof / gDa/Lx?sf] cys kl/>daf6 !(*# O{G6]ssf] Pstf lg/Gt/ cufl8 a9L/x]sf] 5, of] PstfnfO{ ;d[4 agfpg] sfo{df sld 5}g, To;}n] #^ jif{;Ddsf] lg/Gt/ ofqfnfO{ ;fy lbP/ O{G6]snfO{ cfkm\gf] 9's9'sL agfpg] tdfd dxfg'efjk|lt xfdL C0fL 5f}+ . -

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Naval Modernisation in Southeast Asia: Nature, Causes, Consequences

NAVAL MODERNISATION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA: NATURE, CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES 26 – 27 JANUARY 2011 SINGAPORE Naval Modernisation in Southeast Asia: Nature, Causes, Consequences REPORT OF A CONFERENCE ORGANISED BY S.RAJARATNAM SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES (RSIS) NANYANG TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY, SINGAPORE 26-27 JANUARY 2011 SINGAPORE Contents PAGE 1. Overview 3 2. Opening Remarks 3 3. Session I — Introduction 4 4. Session II — Common Themes 6 5. Session III — Southeast Asia Case Studies I 9 6. Session IV — Southeast Asia Case Studies II 12 7. Session V — Naval Modernisation: Alternative Perspectives 15 8. Session VI — Naval Modernisation and Southeast Asia’s Security 18 9. Concluding Remarks 20 10. Programme 21 11. Presenters & Discussants 23 12. Participants 25 13. About RSIS 27 This report summarizes the proceedings of the conference as interpreted by the assigned rapporteurs and editors of the S.Rajaratnam School of International Studies. Participants neither reviewed nor approved this report. The conference adheres to variations of the Chatham House rule. Accordingly, beyond the points expressed in the prepared papers, no attributions have been included in this conference report. 2 NAVAL MODERNISATION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA OvervieW The conference was an extension of an ongoing research strategic and technological. The conference addressed project conducted by the maritime security programme such key questions as whether a naval arms race or arms of S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), dynamic is taking place, and whether contemporary naval to explore the nature, causes and consequences of naval developments are enhancing or undermining regional modernisation in Southeast Asia. Experts and practitioners security. Constraints and challenges facing regional from government, industry and academia discussed the navies were also identified, as well as policy implications drivers and enablers of naval modernisation: political, for Southeast Asia and the wider region. -

Constructing a Gurkha Diaspora

Ethnic and Racial Studies ISSN: 0141-9870 (Print) 1466-4356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rers20 Migrant warriors and transnational lives: constructing a Gurkha diaspora Kelvin E. Y. Low To cite this article: Kelvin E. Y. Low (2015): Migrant warriors and transnational lives: constructing a Gurkha diaspora, Ethnic and Racial Studies, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2015.1080377 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1080377 Published online: 23 Sep 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rers20 Download by: [NUS National University of Singapore] Date: 24 September 2015, At: 00:24 ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES, 2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1080377 Migrant warriors and transnational lives: constructing a Gurkha diaspora Kelvin E. Y. Low Department of Sociology, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore ABSTRACT The Nepalese Gurkhas have often been regarded as brave warriors in the scheme of British military recruitment since the 1800s. Today, their descendants have settled in various parts of South East and South Asia. How can one conceive of a Gurkha diaspora, and what are the Gurkhas and their families’ experiences of belonging in relation to varied migratory routes? This paper locates Gurkhas as migrants by deliberating upon the connection between military service and migration paths. I employ the lens of methodological transnationalism to elucidate how the Gurkha diaspora is both constructed and experienced. Diasporic consciousness and formation undergo modification alongside subsequent cycles of migration for different members of a diaspora. -

ARF Annual Security Outlook 2020

Table of Contents Foreword 5 Executive Summary 7 Australia 9 Brunei Darussalam 25 Cambodia 33 Canada 45 China 65 European Union 79 India 95 Indonesia 111 Japan 129 Lao PDR 143 Malaysia 153 Mongolia 171 Myanmar 179 New Zealand 183 The Philippines 195 Republic of Korea 219 Russia 231 Singapore 239 Sri Lanka 253 Thailand 259 United States 275 Viet Nam 305 ANNUAL SECURITY OUTLOOK 2020 ASEAN Regional Forum 4 ANNUAL SECURITY OUTLOOK 2020 ASEAN Regional Forum FOREWORD Complicated changes are taking place in the regional and global geostrategic landscape. Uncertainties and complexities have been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. We are deeply saddened by the loss of lives and sufferings caused by this dreadful pandemic. Nevertheless, we are determined to enhance solidarity and cooperation towards effective efforts to respond to the pandemic as well as prevent future outbreaks of this kind. Since its founding in 1994, the ARF has become a key and inclusive Forum working towards peace, security and stability in the region. Through its activities, the ARF has made notable progress in fostering dialogue and cooperation as well as mutual trust and confidence among the Participants. In face of the difficulties and challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, ARF Participants have exerted significant efforts to sustain the momentum of dialogue and cooperation, while moving forward with new proposals and initiatives to respond to existing and emerging challenges. At this juncture, it is all the more important to reaffirm the ARF as a key venue to strengthen dialogue, build strategic trust and enhance practical cooperation among its Participants. -

Sapangar Naval Base, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah

CERTIFIED TO ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED TO ISO 9001:2008 CERT. NO. AR 2636 CERT. NO. MY-AR 2636 PROJECT :- SAPANGAR NAVAL BASE, KOTA KINABALU, SABAH LOCATION :- CLIENT :- Kota Kinabalu, Sabah Muhibbah Engineering (M) Bhd PROJECT COST :- COMPLETION DATE :- RM139 Million (US38 Million) 2001 to 2005 Job Description :- The Sapangar Naval Base, located on a promontory, is to house naval installation and facilities, purpose designed and built to meet the current and future needs of the Royal Malaysian Navy. The harbour is located on the east of the promontory, sheltered from prevailing winds with sufficient water depth for ship berthing. Reclamation works for the proposed naval base involved reclaiming useful land areas of about 122 acres with soil treatment for the installation of on-shore facilities and construction of quay structure. The quay comprises of 800 metres berth length and a provision for future extension of 100 metres of berthing space. The construction of the quay at its location will provide for a minimum water depth of 10 metres to cater for the specified range of Navy vessels. The overall layout of the quay at the operation harbour is based on the principle of pier systems, which will offer wide aprons and ample space to allow for easy loading and unloading of vessels. The 3 sided berth can cater for large and small vessels. Continuous service trenches of 1.7 metres wide with removable covers are provided along the front face of the quay. Transverse trenches are provided at suitable locations to feed the front trench. The Detail Works include :- Design of reclamation work, soil treatment, dredging and shore protection work for the reclaimed land for the whole base. -

ECFG-Malaysia-Mar-19.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to help prepare you for deployment to culturally complex environments and successfully achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information it contains will help you understand the decisive cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain necessary skills to achieve Malaysia mission success. The guide consists of two parts: Part 1: Introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment – Southeast Asia in particular (Photo: Malaysian, Royal Thai, and US soldiers during Cobra Gold 2014 exercise). Culture Guide Part 2: Presents “Culture Specific” information on Malaysia, focusing on unique cultural features of Malaysian society. This section is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo: US sailor signs autographs for Malaysian school children). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

MARITIME Security &Defence M

June MARITIME 2021 a7.50 Security D 14974 E &Defence MSD From the Sea and Beyond ISSN 1617-7983 • Key Developments in... • Amphibious Warfare www.maritime-security-defence.com • • Asia‘s Power Balance MITTLER • European Submarines June 2021 • Port Security REPORT NAVAL GROUP DESIGNS, BUILDS AND MAINTAINS SUBMARINES AND SURFACE SHIPS ALL AROUND THE WORLD. Leveraging this unique expertise and our proven track-record in international cooperation, we are ready to build and foster partnerships with navies, industry and knowledge partners. Sovereignty, Innovation, Operational excellence : our common future will be made of challenges, passion & engagement. POWER AT SEA WWW.NAVAL-GROUP.COM - Design : Seenk Naval Group - Crédit photo : ©Naval Group, ©Marine Nationale, © Ewan Lebourdais NAVAL_GROUP_AP_2020_dual-GB_210x297.indd 1 28/05/2021 11:49 Editorial Hard Choices in the New Cold War Era The last decade has seen many of the foundations on which post-Cold War navies were constructed start to become eroded. The victory of the United States and its Western Allies in the unfought war with the Soviet Union heralded a new era in which navies could forsake many of the demands of Photo: author preparing for high intensity warfare. Helping to ensure the security of the maritime shipping networks that continue to dominate global trade and the vast resources of emerging EEZs from asymmetric challenges arguably became many navies’ primary raison d’être. Fleets became focused on collabora- tive global stabilisation far from home and structured their assets accordingly. Perhaps the most extreme example of this trend has been the German Navy’s F125 BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG class frig- ates – hugely sophisticated and expensive ships designed to prevail only in lower threat environments. -

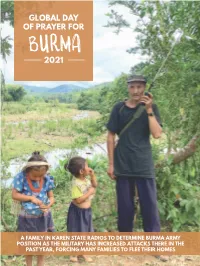

Global Day of Prayer for 2021

GLOBAL DAY OFBURMA PRAYER FOR 2021 A FAMILY IN KAREN STATE RADIOS TO DETERMINE BURMA ARMY POSITION AS THE MILITARY HAS INCREASED ATTACKS THERE IN THE PAST YEAR, FORCING MANY FAMILIES TO FLEE THEIR HOMES From the Director Dear friends, Th ank you for your prayers and love for the people of Burma. Burma has now faced over 70 years of civil war, death, displacement, injustice and sorrow. But we don’t give up praying because God while at the same time preventing over one million 1 has not given up and we see in our own lives how Muslim Rohingya from the same state from God answers prayer and does the impossible. returning. Th e Rohingya were attacked in 2017 and We are told by Jesus to be persistent in prayer, forced to fl ee to refugee camps in Bangladesh where not give up and pray that God‘s kingdom will come they live in squalor with very little likelihood of on earth as it is in heaven. Every time we pray and change. In northern Burma attacks against Kachin, we obey Jesus we feel His presence and we are part Shan and Ta’ang continue with over 100,000 of His kingdom on this earth regardless of the other displaced. In eastern Burma in Karen State there is kingdoms around us. a ceasefi re but it is regularly violated with the killing God works through prayer, fi rst to change of men, women and children. our own hearts and to guide us in what we are to Th ere was an election in November 2020 do, and then to bring change to others.