Naval Modernisation in Southeast Asia: Nature, Causes, Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arms Procurement Decision Making Volume II: Chile, Greece, Malaysia

4. Malaysia Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam* I. Introduction Malaysia has become one of the major political players in the South-East Asian region with increasing economic weight. Even after the economic crisis of 1997–98, despite defence budgets having been slashed, the country is still deter- mined to continue to modernize and upgrade its armed forces. Malaysia grappled with the communist insurgency between 1948 and 1962. It is a democracy with a strong government, marked by ethnic imbalances and affirmative policies, strict controls on public debate and a nascent civil society. Arms procurement is dominated by the military. Public apathy and indifference towards defence matters have been a noticeable feature of the society. Public opinion has disregarded the fact that arms procurement decision making is an element of public policy making as a whole, not only restricted to decisions relating to military security. An examination of the country’s defence policy- making processes is overdue. This chapter inquires into the role, methods and processes of arms procure- ment decision making as an element of Malaysian security policy and the public policy-making process. It emphasizes the need to focus on questions of public accountability rather than transparency, as transparency is not a neutral value: in many countries it is perceived as making a country more vulnerable.1 It is up 1 Ball, D., ‘Arms and affluence: military acquisitions in the Asia–Pacific region’, eds M. Brown et al., East Asian Security (MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass., 1996), p. 106. * The author gratefully acknowledges the help of a number of people in putting this study together. -

The Kra Canal and Thai Security

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2002-06 The Kra Canal and Thai security Thongsin, Amonthep Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/5829 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS THE KRA CANAL AND THAI SECURITY by Amonthep Thongsin June 2002 Thesis Advisor: Robert E. Looney Thesis Co-Advisor: William Gates Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2002 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE: The Kra Canal and Thai Security 5. FUNDING NUMBERS 6. AUTHOR(S) Thongsin, Amonthep 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION REPORT Monterey, CA 93943-5000 NUMBER 9. -

ITU/NBTC Conference on Digital Broadcasting NBTC Works Done on Digital Radio 12 December 2017, Bangkok, Thailand

ITU/NBTC Conference on Digital Broadcasting NBTC works done on Digital Radio 12 December 2017, Bangkok, Thailand Ms Orasri Srisasa Division Director of Digital Broadcasting Bureau Office of NBTC,Thailand 1 Contents Radio Broadcasting Services in Thailand National Digital Broadcasting Plan History of Digital Radio Trial in Thailand Digital Radio Broadcasting Projects DAB+ trial and way forward in Thailand 2 Radio Broadcasting in Thailand: Radio Consumption Radio Reach by Population : BKK and Vicinity 11.242 M 10.969 M 10.865 M 10.474 M 10.14 M 10.004 M 4.5% Jan 17Jan-60Feb 17 Feb-60Apr 17 Mar-60Mar 17 Apr-60May 17 May-60Jul 17 Jun-60 Listening Radio behavior by Device and Location Annual advertising Revenues (Baht): : BKK and Vicinity 401,536,000 379,218,000 Other 346,209,000 368,123,000 2% 323,822,000 324,195,000 Smart Office phone 8% 25% PC Radio By 1% By At Reciever Device Incar Location home 74% 33% 57% Jan-60Jan 17 Feb-60Feb 17 Apr 17 Mar-60Mar 17 Apr-60May 17 May-60Jul 17 Jun-60 Source: Nielsen 3 Radio Broadcasting in Thailand: Media Advertising Expense Spending Media 2015 2016 %Change Terrestial 78,457 67,492 ‐14% Cable/Satellite TV 6,055 3,495 ‐42% Radio 5,675 5,262 ‐7% Newspaper 12,323 9,843 ‐20% Magazine 4,268 2,929 ‐31% Cinema 5,133 5,445 6% Outdoor 4,190 5,665 35% Transit 4,486 5,311 18% In store 645 700 9% Internet 1,058 1,731 64% Unit: Million Baht Source: Nielsen Source: Nielsen 4 Radio Broadcasting Landscapes in Thailand : Incumbent Radio Broadcasters Trial Broadcaster Radio Broadcasters Main Broadcasters Trial Broadcasters 506** (525) 4008*(5,669) Business Public Community AM 193 FM 313 3102* 705* 191* * *Extended right to use radio frequency for 5 years * Currently on‐Air: as of Oct 2017 Current Thai National Frequency Plan . -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Lt-Gen Kyaw Win Meets Departmental Personnel, Locals in Langkho

Established 1914 Volume XIII, Number 148 9th Waxing of Tawthalin 1367 ME Sunday, 11 September, 2005 Four political objectives Four economic objectives Four social objectives * Stability of the State, community peace * Development of agriculture as the base and all-round * Uplift of the morale and morality of and tranquillity, prevalence of law and development of other sectors of the economy as well the entire nation order * Proper evolution of the market-oriented economic * Uplift of national prestige and integ- * National reconsolidation system rity and preservation and safeguard- * Emergence of a new enduring State * Development of the economy inviting participation in ing of cultural heritage and national Constitution terms of technical know-how and investments from character * Building of a new modern developed sources inside the country and abroad * Uplift of dynamism of patriotic spirit nation in accord with the new State * The initiative to shape the national economy must be kept * Uplift of health, fitness and education Constitution in the hands of the State and the national peoples standards of the entire nation Thanks to concerted efforts of national race leaders and local people, sector-wise development is seen in states and divisions Lt-Gen Kyaw Win meets departmental personnel, locals in Langkho Lt-Gen Kyaw Win meeting with officers and other ranks and their family members of Langkho Station. — MNA YANGON, 10 Sept Langkho Stations, met tasks, joining hands with mentation of develop- tary reports on education, ment, the people and the — Member of the State with Tatmadawmen and the local national races. ment projects of rural ar- health and information Tatmadaw combine their Peace and Development family members of He cordially greeted the eas in the district in 2005- matters. -

1 the Royal Thai Navy's Theoretical Application of the Maritime Hybrid

The Royal Thai Navy’s Theoretical Application of the Maritime Hybrid Warfare Concept by Hadrien T. Saperstein In the maritime strategic thought community there has been much talk about the theoretical application of the Maritime Hybrid Warfare concept by second and third-tier naval powers in the Northeast and Southeast Asia sub-regions.i On that theme, a recent publication on the Royal Thai Navy’s maritime and naval strategic thought concluded that the organisation stands at an existential crossroad with the advent of maritime hybrid threats in the grey-zone warfare era and should therefore consider operationalising the aforesaid multi-dimensional maritime concept to its organisational system and material capabilities.ii Since the publication released date though, this conclusion has only become more poignant in light of recent reports that China, a country that has applied the Maritime Hybrid Warfare since 2012,iii has signed a secret agreement giving it access to the Ream Naval Base in Cambodia.iv This newfound foothold at the mouth of the Gulf of Thailand puts a first-tier naval power – the People's Liberation Army Navy – now within striking distance to one of the Royal Thai Navy’s most important naval bases. In response to this event the following article analyses the manner by which the Royal Thai Navy, a second-tier naval power in the Southeast Asia sub-region, could theoretically operationalise the Maritime Hybrid Warfare concept in an effort to combat the soon-to-be present maritime hybrid threats in its internationally-recognised -

Sapangar Naval Base, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah

CERTIFIED TO ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED TO ISO 9001:2008 CERT. NO. AR 2636 CERT. NO. MY-AR 2636 PROJECT :- SAPANGAR NAVAL BASE, KOTA KINABALU, SABAH LOCATION :- CLIENT :- Kota Kinabalu, Sabah Muhibbah Engineering (M) Bhd PROJECT COST :- COMPLETION DATE :- RM139 Million (US38 Million) 2001 to 2005 Job Description :- The Sapangar Naval Base, located on a promontory, is to house naval installation and facilities, purpose designed and built to meet the current and future needs of the Royal Malaysian Navy. The harbour is located on the east of the promontory, sheltered from prevailing winds with sufficient water depth for ship berthing. Reclamation works for the proposed naval base involved reclaiming useful land areas of about 122 acres with soil treatment for the installation of on-shore facilities and construction of quay structure. The quay comprises of 800 metres berth length and a provision for future extension of 100 metres of berthing space. The construction of the quay at its location will provide for a minimum water depth of 10 metres to cater for the specified range of Navy vessels. The overall layout of the quay at the operation harbour is based on the principle of pier systems, which will offer wide aprons and ample space to allow for easy loading and unloading of vessels. The 3 sided berth can cater for large and small vessels. Continuous service trenches of 1.7 metres wide with removable covers are provided along the front face of the quay. Transverse trenches are provided at suitable locations to feed the front trench. The Detail Works include :- Design of reclamation work, soil treatment, dredging and shore protection work for the reclaimed land for the whole base. -

Armed Forces War Course-2013 the Ministers the Hon’Ble Ministers Presented Their Vision

National Defence College, Bangladesh PRODEEP 2013 A PICTORIAL YEAR BOOK NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE MIRPUR CANTONMENT, DHAKA, BANGLADESH Editorial Board of Prodeep Governing Body Meeting Lt Gen Akbar Chief Patron 2 3 Col Shahnoor Lt Col Munir Editor in Chief Associate Editor Maj Mukim Lt Cdr Mahbuba CSO-3 Nazrul Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Family Photo: Faculty Members-NDC Family Photo: Faculty Members-AFWC Lt Gen Mollah Fazle Akbar Brig Gen Muhammad Shams-ul Huda Commandant CI, AFWC Wg Maj Gen A K M Abdur Rahman R Adm Muhammad Anwarul Islam Col (Now Brig Gen) F M Zahid Hussain Col (Now Brig Gen) Abu Sayed Mohammad Ali 4 SDS (Army) - 1 SDS (Navy) DS (Army) - 1 DS (Army) - 2 5 AVM M Sanaul Huq Brig Gen Mesbah Ul Alam Chowdhury Capt Syed Misbah Uddin Ahmed Gp Capt Javed Tanveer Khan SDS (Air) SDS (Army) -2 (Now CI, AFWC Wg) DS (Navy) DS (Air) Jt Secy (Now Addl Secy) A F M Nurus Safa Chowdhury DG Saquib Ali Lt Col (Now Col) Md Faizur Rahman SDS (Civil) SDS (FA) DS (Army) - 3 Family Photo: Course Members - NDC 2013 Brig Gen Md Zafar Ullah Khan Brig Gen Md Ahsanul Huq Miah Brig Gen Md Shahidul Islam Brig Gen Md Shamsur Rahman Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Brig Gen Md Abdur Razzaque Brig Gen S M Farhad Brig Gen Md Tanveer Iqbal Brig Gen Md Nurul Momen Khan 6 Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army 7 Brig Gen Ataul Hakim Sarwar Hasan Brig Gen Md Faruque-Ul-Haque Brig Gen Shah Sagirul Islam Brig Gen Shameem Ahmed Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh -

Sample Chapter

lex rieffel 1 The Moment Change is in the air, although it may reflect hope more than reality. The political landscape of Myanmar has been all but frozen since 1990, when the nationwide election was won by the National League for Democ- racy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi. The country’s military regime, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), lost no time in repudi- ating the election results and brutally repressing all forms of political dissent. Internally, the next twenty years were marked by a carefully managed par- tial liberalization of the economy, a windfall of foreign exchange from natu- ral gas exports to Thailand, ceasefire agreements with more than a dozen armed ethnic minorities scattered along the country’s borders with Thailand, China, and India, and one of the world’s longest constitutional conventions. Externally, these twenty years saw Myanmar’s membership in the Associa- tion of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), several forms of engagement by its ASEAN partners and other Asian neighbors designed to bring about an end to the internal conflict and put the economy on a high-growth path, escalating sanctions by the United States and Europe to protest the military regime’s well-documented human rights abuses and repressive governance, and the rise of China as a global power. At the beginning of 2008, the landscape began to thaw when Myanmar’s ruling generals, now calling themselves the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), announced a referendum to be held in May on a new con- stitution, with elections to follow in 2010. -

MARITIME Security &Defence M

June MARITIME 2021 a7.50 Security D 14974 E &Defence MSD From the Sea and Beyond ISSN 1617-7983 • Key Developments in... • Amphibious Warfare www.maritime-security-defence.com • • Asia‘s Power Balance MITTLER • European Submarines June 2021 • Port Security REPORT NAVAL GROUP DESIGNS, BUILDS AND MAINTAINS SUBMARINES AND SURFACE SHIPS ALL AROUND THE WORLD. Leveraging this unique expertise and our proven track-record in international cooperation, we are ready to build and foster partnerships with navies, industry and knowledge partners. Sovereignty, Innovation, Operational excellence : our common future will be made of challenges, passion & engagement. POWER AT SEA WWW.NAVAL-GROUP.COM - Design : Seenk Naval Group - Crédit photo : ©Naval Group, ©Marine Nationale, © Ewan Lebourdais NAVAL_GROUP_AP_2020_dual-GB_210x297.indd 1 28/05/2021 11:49 Editorial Hard Choices in the New Cold War Era The last decade has seen many of the foundations on which post-Cold War navies were constructed start to become eroded. The victory of the United States and its Western Allies in the unfought war with the Soviet Union heralded a new era in which navies could forsake many of the demands of Photo: author preparing for high intensity warfare. Helping to ensure the security of the maritime shipping networks that continue to dominate global trade and the vast resources of emerging EEZs from asymmetric challenges arguably became many navies’ primary raison d’être. Fleets became focused on collabora- tive global stabilisation far from home and structured their assets accordingly. Perhaps the most extreme example of this trend has been the German Navy’s F125 BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG class frig- ates – hugely sophisticated and expensive ships designed to prevail only in lower threat environments. -

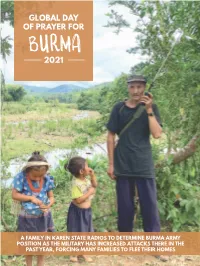

Global Day of Prayer for 2021

GLOBAL DAY OFBURMA PRAYER FOR 2021 A FAMILY IN KAREN STATE RADIOS TO DETERMINE BURMA ARMY POSITION AS THE MILITARY HAS INCREASED ATTACKS THERE IN THE PAST YEAR, FORCING MANY FAMILIES TO FLEE THEIR HOMES From the Director Dear friends, Th ank you for your prayers and love for the people of Burma. Burma has now faced over 70 years of civil war, death, displacement, injustice and sorrow. But we don’t give up praying because God while at the same time preventing over one million 1 has not given up and we see in our own lives how Muslim Rohingya from the same state from God answers prayer and does the impossible. returning. Th e Rohingya were attacked in 2017 and We are told by Jesus to be persistent in prayer, forced to fl ee to refugee camps in Bangladesh where not give up and pray that God‘s kingdom will come they live in squalor with very little likelihood of on earth as it is in heaven. Every time we pray and change. In northern Burma attacks against Kachin, we obey Jesus we feel His presence and we are part Shan and Ta’ang continue with over 100,000 of His kingdom on this earth regardless of the other displaced. In eastern Burma in Karen State there is kingdoms around us. a ceasefi re but it is regularly violated with the killing God works through prayer, fi rst to change of men, women and children. our own hearts and to guide us in what we are to Th ere was an election in November 2020 do, and then to bring change to others. -

NAVAL FORCES USING THORDON SEAWATER LUBRICATED PROPELLER SHAFT BEARINGS September 7, 2021

NAVAL AND COAST GUARD REFERENCES NAVAL FORCES USING THORDON SEAWATER LUBRICATED PROPELLER SHAFT BEARINGS September 7, 2021 ZERO POLLUTION | HIGH PERFORMANCE | BEARING & SEAL SYSTEMS RECENT ORDERS Algerian National Navy 4 Patrol Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 Argentine Navy 3 Gowind Class Offshore Patrol Ships Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2022-2027 Royal Australian Navy 12 Arafura Class Offshore Patrol Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2027 Royal Australian Navy 2 Supply Class Auxiliary Oiler Replenishment (AOR) Ships Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 Government of Australia 1 Research Survey Icebreaker Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 COMPAC SXL Seawater lubricated propeller Seawater lubricated propeller shaft shaft bearings for blue water bearings & grease free rudder bearings LEGEND 2 | THORDON Seawater Lubricated Propeller Shaft Bearings RECENT ORDERS Canadian Coast Guard 1 Fishery Research Ship Thordon SXL Bearings 2020 Canadian Navy 6 Harry DeWolf Class Arctic/Offshore Patrol Ships (AOPS) Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020-2022 Egyptian Navy 4 MEKO A-200 Frigates Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2024 French Navy 4 Bâtiments Ravitailleurs de Force (BRF) – Replenishment Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2027 French Navy 1 Classe La Confiance Offshore Patrol Vessel (OPV) Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 French Navy 1 Socarenam 53 Custom Patrol Vessel Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2019 THORDON Seawater Lubricated Propeller Shaft Bearings | 3 RECENT ORDERS German Navy 4 F125 Baden-Württemberg Class Frigates Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2019-2021 German Navy 5 K130