World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agrarian Practices and Land Transactions in the Ivory Coast Cashew Basin

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 10, Ver. 3 (October. 2018) 51-58 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Agrarian practices and land transactions in the Ivory Coast cashew basin. Dr. N’DA KouassiPékaoh Enseignant-Cherhcheur Université Jean LorougnonGuédé (Daloa) Corresponding Author: Dr. N’DA KouassiPékaoh Résumé: La culture de l’anacarde connait une forte croissance dans les régions de savane en Côte d’Ivoire. Elle est produite dans 19 régions du pays et s’impose désormais comme la principale source de revenus pour les populations locales et participe de facto à la constitution du PIB national. Cependant, le développement de cette économie arbustive, consommatrice de terres, n’est pas sans conséquences sur les rapports socio- communautaires dans une zone traditionnellement dédiée aux cultures annuelles. A partir d’enquêtes quantitatives et qualitatives conduites dans quatre (4) sous-préfectures de la région du Béré (Kounahiri, Bouandougou, Dianra et Mankono), cet article décrit les rapports fonciers en cours de recompositions dans le bassin anacardier et analyse les incidences au niveau écologique et social liées au développement de cette filière agricole. Mots clés: Foncier, anacarde, agriculture, environnement, sécuritéfoncière Abstract : The cashew crop is experiencing strong growth in the savanna regions of Côte d'Ivoire. It is produced in 19 regions of the country and is now the main source of income for local populations and participates de facto in the constitution of the national GDP. However, the development of thisshrubbyeconomy, consuming land, is not withoutconsequences on the socio-community relations in an area traditionallydedicated to annualcrops. -

Region Du Bere Sommaire Sommaire

REGION DU BERE SOMMAIRE SOMMAIRE ...............................................................................................................................................................1 AVANT PROPOS ........................................................................................................................................................6 PRESENTATION .........................................................................................................................................................7 REMERCIEMENTS ......................................................................................................................................................8 MOT DE MADAME LE MINISTRE ...............................................................................................................................9 A. PRESCOLAIRE ..................................................................................................................................................... 10 A-1. DONNEES SYNTHETIQUES .......................................................................................................................... 11 Tableau 1 : Répartition des infrastructures, des effectifs élèves et des enseignants par département, par sous-préfecture et par statut ........................................................................................................................ 12 Tableau 2 : Répartition des élèves par niveau d’études selon l’âge ............................................................. 13 -

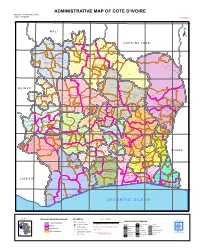

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

5 Geology and Groundwater 5 Geology and Groundwater

5 GEOLOGY AND GROUNDWATER 5 GEOLOGY AND GROUNDWATER Table of Contents Page CHAPTER 1 PRESENT CONDITIONS OF TOPOGRAPHY, GEOLOGY AND HYDROGEOLOGY.................................................................... 5 – 1 1.1 Topography............................................................................................................... 5 – 1 1.2 Geology.................................................................................................................... 5 – 2 1.3 Hydrogeology and Groundwater.............................................................................. 5 – 4 CHAPTER 2 GROUNDWATER RESOURCES POTENTIAL ............................... 5 – 13 2.1 Mechanism of Recharge and Flow of Groundwater ................................................ 5 – 13 2.2 Method for Potential Estimate of Groundwater ....................................................... 5 – 13 2.3 Groundwater Potential ............................................................................................. 5 – 16 2.4 Consideration to Select Priority Area for Groundwater Development Project ........ 5 – 18 CHAPTER 3 GROUNDWATER BALANCE STUDY .............................................. 5 – 21 3.1 Mathod of Groundwater Balance Analysis .............................................................. 5 – 21 3.2 Actual Groundwater Balance in 1998 ...................................................................... 5 – 23 3.3 Future Groundwater Balance in 2015 ...................................................................... 5 – 24 CHAPTER -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

REGION DU BÉRÉ Sommaire

REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE Union-Discipline-Travail MINISTERE DE L’EDUCATION NATIONALE Statistiques Scolaires de Poche 2015-2016 REGION DU BÉRÉ Sommaire Sommaire ..................................................................................................... 2 Sigles et SiglesAbréviations et AbréviationsSommaire ................................................................ ................... 2 Méthodologie ............................................................................................... 2 Introduction.................................................................................................. 2 1/ Résultats du Préscolaire 2015-2016 ........................................................ 2 1-1 / Chiffres du Préscolaire en 2015-2016 ............................................ 2 1-2 / Indicateurs du Préscolaire en 2015-2016 ...................................... 2 1-3 / Préscolaire dans les Sous-préfectures en 2015-2016 .................. 2 2/ Résultats du Primaire 2015-2016 ............................................................ 2 2-1 / Chiffres du Primaire en 2015-2016 ................................................ 2 2-2 / Indicateurs du Primaire en 2015-2016 ........................................... 2 2-3 / Primaire dans les Sous-préfectures en 2015-2016 ........................ 2 3/ Résultats du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016 ..................................... 2 3-1 / Chiffres du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016 ............................... 2 3-2 / Indicateurs du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016 -

Décret N° 95-941 Du 13 Décembre 1995 Portant Création De Nouvelles Communes

Décret n° 95-941 du 13 décembre 1995 portant création de nouvelles communes Article 1er : Sont érigés en communes les 61 chefs-lieux de département et de sous- préfectures ci-après désignés : REGION DU SUD DEPARTEMENT D'ABIDJAN : Songon DEPARTEMENT D'ABOISSO : Maféré, Tiapoum DEPARTEMENT DE TIASSALE : Taabo REGION DU SUD-OUEST DEPARTEMENT DE SAN-PEDRO : Grand-Béréby DEPARTEMENT DE SASSANDRA : Gueyo DEPARTEMENT DE SOUBRE : Buyo, Grand-Zattry, Méadji DEPARTEMENT DE TABOU : Grabo REGION DU CENTRE DEPARTEMENT DE BONGOUANOU : Tiémélékro, Anoumaba DEPARTEMENT DE DAOUKRO : Ettrokro DEPARTEMENT DE TOUMODI : Kokoumbo, Djékanou DEPARTEMENT DE YAMOUSSOUKRO : Tié-N'diékro REGION DU CENTRE-NORD DEPARTEMENT DE BOUAKE : Djébonoua DEPARTEMENT DE DABAKALA : Foumbolo, Satama-Sokoura DEPARTEMENT DE KATIOLA : Tortiya DEPARTEMENT DE SAKASSOU : Sakassou REGION DU CENTRE-OUEST DEPARTEMENT DE BOUAFLE : Bonon DEPARTEMENT DE DALOA : Bédiala, Gboguné DEPARTEMENT D'OUME : Diégonéfla REGION DU NORD DEPARTEMENT DE FERKESSEDOUGOU : Kong, Koumbala DEPARTEMENT DE KORHOGO : Guiembé, Karakoro, Koumborodougou, Niofoin, Tioroniaradougou DEPARTEMENT DE TENGRELA : Kanakono REGION DU NORD-EST DEPARTEMENT DE BONDOUKOU : Sandégué DEPARTEMENT DE BOUNA : Doropo DEPARTEMENT DE TANDA : Assuéfry, Transua REGION DU NORD-OUEST DEPARTEMENT DE MANKONO : Dianra, Kounahiri, Kongasso, Sarhala DEPARTEMENT D'ODIENNE : Bako, Dioulatiédougou, Goulia, Kaniasso, Séguélon, Seydougou,Tienko DEPARTEMENT DE SEGUELA : Djibrosso, Dualla, Massala, Marondo, Sifié, Worofla DEPARTEMENT DE TOUBA : Booko, Guintéguéla, Koonan, Koro REGION DE L'OUEST DEPARTEMENT DE MAN : Sangouiné DEPARTEMENT DE BIANKOUMA : Gbonné DEPARTEMENT DE GUIGLO : Taï. Article 2 : Les limites territoriales des communes ci-dessus visées seront fixées par décret en conseil des ministres. Article 3 : Le ministre de l'intérieur est chargé de l'exécution du présent décret qui sera publié au Journal Officiel de la République de Côte d'Ivoire. -

Migrations Cotonnières Sénoufo : Premiers Résultats

OFFICE DE LA RECHIiRCk-IE MlNISTERE DG PLAN ET SCIENTIFIQUE ET TECHNIQI~l~ DE L’Ir\iDüSTRIE OUTRE -MER MIGRATIONS COTONNIÈRES SENOUFO Premiers résultats Xavier LE ROY Juillet 1981 CENTRE ORSTOM DE PETIT BASSAM 04 BP 293 ABIDJAN 04 Avw La cal!labohaLion de : - Nawolo SORO, pour les enquêtes, le dépouillement et la codification ; - Lévétiéwin KAFAO, pour les enquêtes, e dépouillement et les relevés de parcelles ; - Daouda COULIBALY, Doma KONE, Seydou OUATARA, pour les enquê- tes et le dépouillement ; - Blandine CROUZIER, pour la dacty lographie, le dépou .il lement et la codification ; - Jean-François FOUCHER, lors au traitement informatique ; - Huguette THUILIER, pour les cartes ; - Baba GROUPESSIE, pour les diagrammes. Awc &x cotitibtiun des agents de la C. 1. D. T, : messieurs les Directeurs de secteur, chefs de zone, assistants et moniteurs, des secteurs C. 1. D. T. de Mankono, Korhogo, Séguéla, Bouaflé. Avec LQ cancum des migrants cotonniers sénoufo des départe- ments de Mankono et Korhogo. 2 S 0 MMA 1 RE Page Introduction 5 C!L?PITRE 1 Ensemble de la région d'accueil 12 CtUPITRE II Principale region d'accueil 30 Conclusion 61 Ensemble de la région d'accueil - - Culture cotonnière par zone et par ethnie 19 - Culture cotonnière des migrants senoufo, par village 23 1 - Principale région d'accueil : zones Dianra malinké, Dikodougou malinké, Sarhala 23 2 - Principale région d'accueil : zone Marandala 24 3 - Principale région d'accueil : zones Mankono et Tiéningboué 25 4 - Frange Sénoufo : zones Dianra sénoufo, Dikodougou sénoufo, Morondo-Kani -

Spatial Availability of Nitrogen and Pesticides in the Surface Layers Of

Journal of Agricultural Chemistry and Environment, 2021, 10, 143-168 https://www.scirp.org/journal/jacen ISSN Online: 2325-744X ISSN Print: 2325-7458 Spatial Availability of Nitrogen and Pesticides in the Surface Layers of Agricultural Soils of Tropical Hydrosystems in the Wet Season: Case of the Béré Watershed in Côte d’Ivoire (West Africa) Mian Germain Eba1,2*, Kouakou Sylvain Akpo1, Pétémanangnan Jean-Marie Ouattara1, Tiangoua Koné1, Lacina Coulibaly1,3 1Environment and Aquatic Biology Laboratory, Nangui Abrogoua University, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire 2Central Environment Laboratory, Ivorian Antipollution Center, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire 3Department of Chemistry, University of Man, Man, Côte d’Ivoire How to cite this paper: Eba, M.G., Akpo, Abstract K.S., Ouattara, P.J.M., Koné, T. and Couli- baly, L. (2021) Spatial Availability of Ni- The objective of this study was to assess the contribution of the spatial organi- trogen and Pesticides in the Surface Layers zation of cropping systems and the physicochemical properties of surface layers of Agricultural Soils of Tropical Hydrosys- of the agricultural zones soils in tropical hydrosystems to the spatial availability tems in the Wet Season: Case of the Béré Watershed in Côte d’Ivoire (West Africa). of nitrogen and pesticides during the wet season, such as the Béré watershed Journal of Agricultural Chemistry and (BW) in Côte d’Ivoire. For this purpose, after mapping the spatial distribution Environment, 10, 143-168. of the BW cropping systems based on the likelihood classification methodology https://doi.org/10.4236/jacen.2021.102010 of satellite images of the study area, 27 samples from the 0 - 20 cm horizon of Received: February 11, 2021 the soil surface layers of the agricultural areas were taken during the wet and Accepted: March 29, 2021 agricultural season of the year 2016. -

Cote D'ivoire-Programme De Renforcement Des Ouvrages Du

REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE UNION – DISCIPLINE – TRAVAIL -------------------------------- MINISTERE DU PETROLE, DE L’ENERGIE ET DES ENERGIES RENOUVELABLES --------------------------------- PLAN CADRE DE REINSTALLATION DU PROGRAMME DE RENFORCEMENT DES OUVRAGES DU SYSTEME ET D’ACCES A L ’ELECTRICITE (PROSER) DE 253 LOCALITES DANS LES REGIONS DU BAFING, DU BERE, DU WORODOUGOU, DU CAVALLY, DU GUEMON ET DU TONKPI RAPPORT FINAL Octobre 2019 CONSULTING SECURITE INDUSTRIELLE Angré 8ème Tranche, Immeuble ELVIRA Tél :22 52 56 38/ Cel :08 79 54 29 [email protected] Plan Cadre de Réinstallation du Programme de Renforcement des Ouvrages du Système et d’accès à l ’Electricité (PROSER) de 253 localités dans les Régions du Bafing, du Béré, du Worodougou, du Cavally, du Guémon et du Tonkpi TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES ACRONYMES VIII LISTE DES TABLEAUX X LISTE DES PHOTOS XI LISTE DES FIGURES XII DEFINITION DES TERMES UTILISES DANS CE RAPPORT XIII RESUME EXECUTIF XVII 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Programme de Renforcement des Ouvrages du Système et d’accès à l ’Electricité (PROSER) de 253 localités dans les Régions du Bafing, du Béré, du Worodougou, du Cavally, du Guémon et du Tonkpi 1 1.1.1 Situation de l’électrification rurale en Côte d’Ivoire 1 1.1.2 Justification du plan cadre de réinstallation 1 1.2 Objectifs du PCR 2 1.3 Approche méthodologique utilisée 3 1.3.1 Cadre d’élaboration du PCR 3 1.3.2 Revue documentaire 3 1.3.3 Visites de terrain et entretiens 3 1.4 Contenu et structuration du PCR 5 2 DESCRIPTION DU PROJET 7 2.1 Objectifs -

458 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'ivoire 17 Avril 2017

458 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE 17 avril 2017 DECRET n°2016-J153 du 28 décembre 2016 relatifau zonage Les ZDC, au nombre de deux, portent les numéros onze et agro-industrieldans lafilière coton. dix-huit. LE PRESIDENTDE LA REPUBLIQUE, Art. 3. -Les ZEA sont constituées de zones optimales de pro Sur rapport conjoint du ministrede l'Agriculture et du Développement duction et de collecte définiesautour d'unités d'égrenage. rural,du ministrede !'Industrie et des Mines, du ministredu Commerce, Une mission d'encadrement agricole, d'achat de coton-graine du ministre auprès du Premier Ministre, chargé du Budget et du Porte et de développement de la filière coton au sein des ZEA est feuille de l'Etat et du ministre auprès du Premier Ministre, chargé de confiée, par délégation, à un opérateur privé unique. l'Economie et des Finances, Art. 4. - La mission prévue à l'alinéa précédent est accomplie Vu la Constitution; dans le cadre d'une convention de concession conclue entre la Vu le règlement n°02/2002/CM/UEMOA du 23 mai 2002 sur les société cotonnière attributairede la ZEA et l'organe chargé de la pratiques commerciales anticoncurrentielles; régulation de la filière. Cette convention précise les conditions Vu la loi n°2013-656 du 13 septembre 2013 fixant les règles relatives et modalités d'exécution de cette mission. à la commercialisation du coton et de l'anacarde et à la régulation des activités des filièrescoton et anacarde; Art. 6. - Les ZEA sont attribuées aux sociétés cotonnières ° Vu l'ordonnance n 2011-473 du 21 décembre 2011 relative aux conformémentau tableau figuranten annexe 2 du présent décret. -

Côte D'ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire Risk-sensitive Budget Review UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction UNDRR Country Reports on Public Investment Planning for Disaster Risk Reduction This series is designed to make available to a wider readership selected studies on public investment planning for disaster risk reduction (DRR) in cooperation with Member States. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) Country Reports do not represent the official views of UNDRR or of its member countries. The opinions expressed and arguments employed are those of the author(s). Country Reports describe preliminary results or research in progress by the author(s) and are published to stimulate discussion on a broad range of issues on DRR. Funded by the European Union Front cover photo credit: Anouk Delafortrie, EC/ECHO. ECHO’s aid supports the improvement of food security and social cohesion in areas affected by the conflict. Page i Table of contents List of figures ....................................................................................................................................ii List of tables .....................................................................................................................................iii List of acronyms ...............................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgements ...........................................................................................................................v Executive summary .........................................................................................................................